CONTRARY to an opinion held by some researchers, a new analysis of more than 20 years of historical data has found no evidence that the increasing number of large icebergs detected off Antarctica’s coasts is a result of global warming.

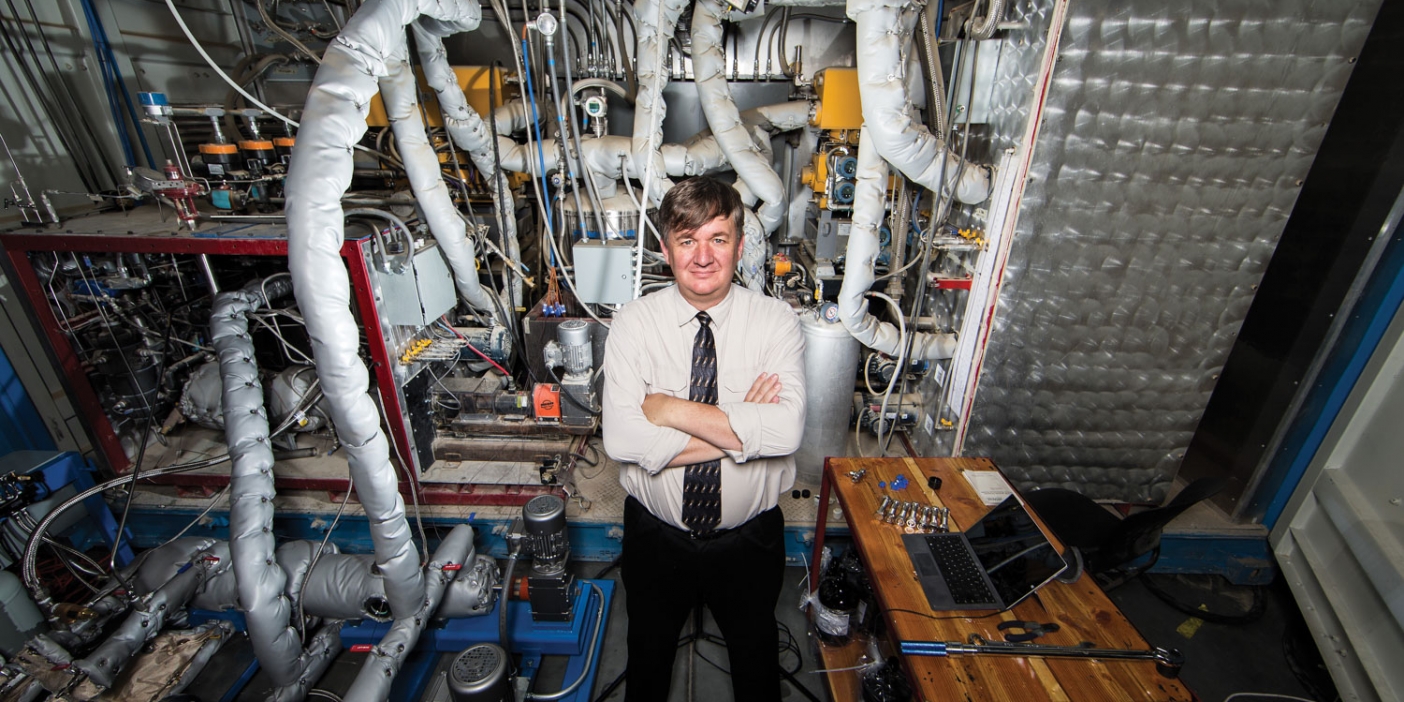

“The dramatic increase in the number of large icebergs as recorded by the National Ice Center database does not represent a climatic change,” says BYU electrical engineering professor David G. Long, ’82, who, with Cheryl Bertoia of the U.S. National Ice Center, reports these findings in a recent issue of EOS Transactions, a publication of the American Geophysics Union. “Our reanalysis suggests that the number of icebergs remained roughly constant from 1978 to the late 1990s.”

Using BYU‘s supercomputers, Long enhanced images of the waters around Antarctica transmitted by satellite. Comparing this data to records from the federal government’s National Ice Center, which tracks icebergs larger than 10 miles on one side, he determined that previous tracking measures were inadequate, resulting in a gross undercounting.

An additional recent spike in large icebergs can be explained by periodic growth and retraction of the large glaciers that yield icebergs every 40 to 50 years, he says, noting previous research done by other scientists.

“Dr. Long’s analysis shows that the increase is only an ‘apparent increase’ and that it is premature to think of any connection between this kind of iceberg growth and global warming,” says Douglas MacAyeal, a University of Chicago glaciologist who tracks icebergs. “His research, particularly that with his amazing ability to detect and track icebergs, is really the best method” for determining the actual rate of iceberg creation.

Long is careful to distinguish between the birth of large icebergs and the widely publicized collapse of the Larsen B ice shelf last year, which yielded many smaller icebergs. Other scientists have clearly shown, Long says, that the event was the result of localized warming.

Referring to his current study, he says, “This data set is not evidence of global warming. Nor does it refute global warming.”

Long and his student assistants have pioneered the use of images generated from the SeaWinds-on-QuikSCAT satellite for tracking icebergs.

The NASA satellite carries a device called a scatterometer, which measures wind speed and direction by recording the reflection of radar beams as they bounce off ocean waves. Until recently, the resolution of the images generated by the scatterometer was too low to distinguish icebergs. Long’s team developed a computer-processing technique that produces images sharp enough to reliably track icebergs.

The BYU group has been working with the National Ice Center since 1999, when Long rediscovered a massive iceberg, the size of Rhode Island, threatening Argentine shipping lanes. The Ice Center had lost track of it because of cloudy skies.

Both Long and MacAyeal say this study does not rule out the possibility that global warming is occurring or that it could have a future effect on the creation of large icebergs.

“Global warming is real,” Long says. “The issues are—is this strictly man-made or is it part of normal cycles? There is evidence to support both sides on that one.”

BYU Today