Recalling a particularly poignant moment, BYU sociologist Brian K. Barber tells of visiting a class of 14-year-old boys at a school in Rafah, a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip. After they asked him the typical questions—”How old are you? Are you married?”—they asked other things he had also heard before, questions revealing an insecurity and woundedness that, he says, “has seeped into their very identity.” It was then, he says, that he felt moved “to tell them that they were good, that they were lovable.” As he turned to leave, the boys gave him a standing ovation, and one of them at the back said, “Please go back to America and tell them we are not all terrorists.”

Politics are an omnipresent facet of Palestinian life, Barber says. Where casual conversation among Americans might turn to sports or the stock market, daily discussion among Palestinians is consumed by politics. Through radio and television, Barber says, most Palestinians are keenly attuned to the larger currents that affect their political and personal destinies. As a consequence, they are acutely aware of international perceptions of them and suffer deep pain because they are regarded so differently from how they see themselves.

An associate professor of sociology, Barber has spent the last six years researching among Palestinian families in the West Bank and Gaza. His work focuses on adolescent development—specifically, how Palestinian youth have fared growing up in times of conflict. Barber describes the 1987–93 Palestinian revolt against Israeli occupation—a movement known as the Intifada—as a laboratory where political, social, and economic pressures combined to offer a unique glimpse into adolescent development under conditions of severe stress.

But such a clinical image conveys little of his immersion in Palestinian life—the months spent learning Arabic, living with the people, and growing to love them. Barber’s research on the socialization of children has also taken him to Colombia, South Africa, India, and Bosnia; he has traveled 250,000 miles in the last three years. But Palestine is where his affinities lie, and it is the core of his research effort.

When he first heard about the possibility of doing research in Gaza, however, Barber had to look at a map to see where it was. He had no political agenda; his interest in the situation was “purely scientific,” he says.

Isolated from the world, Gazan Palestinians call their homeland “the big prison”—a strip of land on the Mediterranean Sea averaging 5 miles wide and 25 miles long, fenced and guarded by the Israeli military on the north, on the east, and along the Gaza/Sinai border to the south. This is strategic ground, a historically contested crossroads between Africa and Eurasia with a legacy of occupation by ancient Egypt, Rome, the Ottoman Turks, the British, and, since 1967, Israel.

More than one million people now live in Gaza, most of them families of refugees from the 1948 war with Israel, known to Palestinians as al-naqba—”the disaster.” Since then, cinder block buildings have supplanted tent housing in camps built by the United Nations, but resources are scarce and unemployment hovers around 50 percent. It is one of the poorest and most densely crowded places on earth. In 1987 pride, frustration, and anger combined to foment a spontaneous uprising against Israel. Carried out by all sectors of society, with youth playing a major role, the movement achieved a measure of autonomy for Gazans. With the establishment of the Palestinian National Authority in 1994, Palestinian Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat moved his headquarters from Tunis to Gaza City.

RESEARCH ORIGINS

A BYU study of the Palestinian family was first proposed by J. Bonner Ritchie, a BYU professor of public management. In the early 1990s when Ritchie began consulting with Palestinian businessmen and educators, many of them told him the same thing: “The Palestinians are worried about their families.” Ritchie reported back to the BYU administration and suggested that a study be done. Sociology professor Bruce A. Chadwick took the lead of the project, reviewed the relevant literature, and enlisted Barber and fellow BYU sociologist Tim B. Heaton. The three were later joined by Camille Fronk and Ray L. Huntington, then PhD candidates in sociology. Fadi Nahhas, a Palestinian from East Jerusalem and a BYU graduate student at the time, provided contacts in his homeland. In the spring of 1994, the team, described by Barber as “five novices,” visited the Palestinian West Bank and East Jerusalem. There they met with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA), the agency responsible for the educational, medical, and relief needs of Palestinian refugees in the Middle East.

BYU researcher Brian Barber (left) visits the Mediterranean Sea with Ahmed, the nephew of Barber’s Gazan host. In Gaza Barber has found a youth population that weathered the Intifada surprisingly well. And for at least some of them, he has become more than a researcher. Ahmed says, “Brian is like father – not friend or brother, but father.”

Concluding that family interviews would be impractical on a large scale, the team set about creating a survey to be administered through the schools. Team members submitted questions according to their specialties: Chadwick, marital satisfaction; Heaton, demographics; Barber, socialization of children. Fronk and Huntington emphasized gender issues. “It was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” Fronk says. “We wanted to find out as much as we could.”

After several rounds of translation and pilot testing, this zeal coalesced in a 25-page Arabic document. Then the researchers began the arduous task of placing the survey in all of the 64 UNRWA schools in the West Bank and training principals to administer it. About 3,500 ninth graders in the West Bank—along with both parents of each student—participated.

Sheer volume and the corresponding weight of the questionnaires posed a challenge. “We worked our tails off,” Barber relates. “Sometimes the back of the car was weighed down so low I didn’t know if we’d make it.”

For their trouble, participants received a plastic retractable BYU pen. According to Fronk, some respondents sent pictures with their completed surveys and expressed thanks for the survey as well as the pen. “They were grateful we would ask,” she says. “It was endearing.”

The Jerusalem/West Bank effort raised a question for Barber: “How can you understand Palestine without Gaza?” After gaining approval from school administrators there, he and Huntington surveyed another 3,500 students and their parents in the Gaza Strip.

The resulting baseline information on Palestinian Arabs in the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza was the first of its kind and sheds light on important questions. How much did the Intifada change Palestinian society? Did participation of women, teenagers, and children as stone throwers, tire burners, sentinels, and flag bearers destabilize the community? And did women’s involvement redefine traditional gender roles? The answer to all of the above: not as much as some observers might have thought.

The survey results signal that the Palestinian family is intact and resilient. One telling figure: a divorce rate of less than 1 percent. Critics scoff and suggest that the marriages must be miserable, but Huntington says, “We have the figures to show that they’re happily married” (this in spite of the fact that only about half had spoken to their spouses before marriage). Marital commitment undergirds other important findings, such as strong parental involvement in children’s schoolwork and close supervision of other activities.

And though today’s Palestinian women are better educated than their mothers were, after active involvement in the Intifada, most returned to traditional roles in the home. Fronk and Huntington, now BYU assistant professors of ancient scripture, conclude, “Despite a great deal of exposure to education, political movements, and contact with the West through the media and Israeli society, the Palestinian family has maintained its traditional gender roles and withstood significant pressure to change.”

DELVING DEEPER INTO THE CULTURE

Barber visits with his host, Mohammed, a 1998 BYU graduate, in the family orchard. Like his homeland, Mohammed’s family property has been both a refuge and a scene of conflict.

Data from the survey has provided grist for student dissertations (including those of Fronk and Huntington), numerous published articles, and a book in progress. And Barber has continued an intense focus on Palestine and the Intifada experience.

When Barber travels to Gaza—which he does regularly—his social calendar fills quickly. “There is little else to do in Gaza but visit family and friends,” he says. “No theaters, bowling alleys, concert halls, or shopping malls—so it isn’t clear how much of this socializing is cultural and how much is a function of the absence of other diversions.”

The socializing includes a full slate of meal appointments. Eaten from a communal platter, meals are an important part of establishing trust and friendship in Palestine. They are also part of the groundwork for Barber’s continuing research, which relies heavily on extended interviews and a second survey of youth, conducted in 1998 with funding from the Social Science Research Council in New York City.

In 1996 Barber began extensive interviews with Intifada youth, including Hussam, twice imprisoned in the Negev Desert; Naji, paralyzed by a bullet to the spine; and Waheed, one of a group of prisoners deported to Lebanon. What really prompted their participation? The interviews yield what Barber calls “crystallizing moments”—moments when, because of what they had observed or experienced personally, they believed they could no longer stand by passively.

Mohammed’s brother Tarik (left) and nephew Ahmed enjoy more tranquil times from the roof of the family home – used during the Intifada to monitor Israeli troop activities.

Up to 80 percent of Palestinian youth voluntarily participated in the uprising—an extraordinary level, considering that 10 to 20 percent of youth took part in other documented political movements, such as the American Vietnam War protests and movements in Northern Ireland and South Africa. Not surprisingly, Intifada participation was highest in Gaza and among children from the poorest and most beleaguered neighborhoods. Devotion to Islam was also a factor: the more religious the youth, the more active in the resistance they were likely to be. The six-year involvement of many youth indicates to Barber that their participation was not frivolous—a product of caprice or thrill seeking—but was inspired by a genuine desire to act in behalf of their society despite considerable risk.

Their impact was considerable as well. Whereas adolescents in Western society have been described as disenfranchised from useful, contributive labor, Barber says Palestinian youth not only participated fully in the Intifada but also provided significant leadership for the movement. To Barber, Palestinian youth provide demonstrable proof that youth can act competently and achieve intended ends. Prominent in the front lines, he says, they were “harassed, shot at, arrested, detained, and imprisoned” more than other sectors of Palestinian society.

But if adolescent competence has been vindicated by retrospective observations of the Intifada, how are these “children of war” doing now? Barber notes that other empirical studies of the Intifada report negative consequences. For example, one study found that traumatic events suffered by children—tear gas attacks, night raids, broken bones—were associated with psychological adjustment problems.

The BYU study bears out inescapable consequences of war-like experience, including two direct correlations: Females harassed by Israeli soldiers experienced higher levels of depression, and males most active in the movement now show higher levels of tobacco use. But the research reveals that, overall, Palestinian youth have proven surprisingly resilient.

Barber found that the strength of the social fabric was an important factor. Stabilizing elements, such as parental approval and support, communication networks, and religion, permeate Palestinian culture to such a level that, Barber concludes, they buffered the severity of the trauma children experienced. Barber is comparing his Gaza findings with Bosnia, a disrupted community where the support structures are not as strong. After a recent trip there he noted, “These youth have not coped nearly as well with the trauma as Gazan youth have.”

More fundamentally, Barber believes that the psychological effect of the conflict hinged on the meaning individuals might attach to it. The sense of doing something necessary for the welfare of their people blunted the trauma of war.

In fact, he writes, “The more youth were involved in the resistance movement, the higher are their current levels of psychological well-being and social and civic functioning. Active youth feel good about themselves and their identity and are actively involved in political organizations and in volunteer service in the community.”

For many Palestinian youth, civic involvement finds expression through education. Barber notes that Palestinians respond readily to opportunity and that, with unemployment high, “Education has long been the key to any type of meaningful employment or social mobility.” Hussam, now a graduate student at BYU, relates in Barber’s interviews that even when he was heavily involved in the Intifada he continued to study. His father exhorted him to “be aware. Just be aware, and maintain your studies during the actions.”

Barber also found that for many incarcerated Palestinians, Israeli prisons became “academies” of the revolt, with rigorous days of study and strategizing. In some cases, the Intifada was conducted with leadership formed within the prisons. In a remarkable example of dedication to learning, Waheed tells of his deportation to Lebanon in a group of 415 Palestinians. Though they tried to escape, it was impossible. “They started shooting over our heads and we were afraid,” he says. “So we decided to organize our days and time and work.” Since there were 80 university students and 30 professors among them, they started a university—with accreditation from the home institution. As part of a lab he was taking, with the help of his professor, Waheed even started a small museum featuring snakes and foxes. “Though it was a severe and very difficult time,” he says, “this experience changed my life from misery to a gift, from deportation to a journey.”

In a recent essay (in Roots of Civic Identity,ed. Miranda Yates and James Youniss [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999]) Barber considers the paradoxical outcomes of youthful Intifada experiences. One irony stands out. Their involvement wrested young participants forcibly from childhood and thrust them into adult roles. This accelerated maturation process left them with new self-knowledge and capabilities, but, he writes, “It is a strange and unsettling experience . . . to realize how little opportunity there is for this growth to be used or expressed in the social structures there.”

Barber finds that post-Intifada frustrations have, for some, called the validity of the whole movement into question. While some of the participants interviewed relate feelings of cautious optimism, others feel a palpable sense of defeat and despair. “So much so,” he writes, “that some expressed a sentimental desire to return to the movement just to reexperience the unity” they felt then.

For Barber, Gaza itself presents a series of contradictions: Abject poverty just off of beachfront real estate. A man assiduously ironing his clothes and applying cologne before stepping into the relative squalor of the street. (“These are not slovenly people,” Barber says.) Consuming political concern among a people who have little control over their political destiny. A quiet, respectful people, deferential toward authority, who conducted a prolonged rebellion. A people who value education and learning yet have few outlets for the skills they seek to gain.

From this paradoxical balance between hope and discouragement, Barber has distilled some overarching lessons. First, “how robust hope can be—the almost naive belief that, despite years of disappointment and betrayal, things will get better.” Second, Barber is often moved by the joy of people who are humble, long-suffering, and poor. He says, “It’s a profound experience to witness firsthand how people find joy in life in the absence of accoutrements.”

Once while walking in Gaza with a friend, Adnan, Barber felt tired and wanted to return to the amenities of Jerusalem. But as he thought about it, he recognized that Adnan had always been in Gaza—there was no other place for him to go. Then Barber had something of an epiphany. He looked at Adnan, handsome, clean, well dressed, intelligent, and caring—for his family and others. How is it, he thought, that such a grand person came from this environment? It was then, he says, that he began “to appreciate what it is to be human—that it has nothing to do with possessions. It’s the ability to develop potential despite surroundings and despite persecution.” In the presence of such people, “seeing them in circumstances we see as appalling,” Barber says, “we want to be with them more. It’s like being treated to a lesson or display of humanness you didn’t know existed.”

THE GAZA EXPERIENCE

Indeed, Barber has spent so much time in Gaza that he has become somewhat of a luminary there. As his driver, Daoud, shuttles us from Jerusalem to Gaza, he smiles as he comments on Barber’s renown, saying, “He is president of United States.”

Barber’s friend Mohammed picks us up at Erez Crossing and takes us to Maghazi, one of eight refugee camps, where we get situated in his second-floor flat—one of six units in a large apartment-like structure housing his extended family. The March day is warm enough that he leaves an outside door open, affording a view of the sizable family orchard below. Ahmed, Mohammed’s nephew, boils water and makes tea from fenugreek seed, sage, and sugar. We drink this traditional Middle Eastern offering from small glass cups in a sitting room displaying Mohammed’s BYU diploma and a map of Palestine.

Somehow the tablecloth, with its cross-stitched images of campus landmarks and the Cougar mascot—a token of Mohammed’s graduate experience in Provo—seems out of place in Palestine. Perhaps to some in Gaza, what he learned at BYU does, too. After earning a master’s degree in educational leadership in 1998, he is under consideration for a promotion to district superintendent within Gaza’s strict and very traditional school system. One colleague, Mohammed relates, has seemed hostile, saying that Mohammed’s ideas are “too Western.” Yet within two days he gets the job. Afterward he is noticeably more relaxed. As the oldest son, he assumed responsibility for his mother, two younger sisters, and four younger brothers when his father died 25 years ago. No doubt, a top position within the school system helps to even out risk in a household where three of the brothers look for work.

Mohammed’s mother and her grandchildren play in the family orchard. A BYU study of the Palestinian family found that strong traditions of family unity and shared community values helped Palestinians cope with the challenges of the Intifada.

Enticed outside by the warm afternoon, we walk through the fruitful orange grove. After the 1948 war Mohammed’s father donated land from the orchard to help shelter Palestinians fleeing the conflict with Israel. What remains has stood as a refuge of sorts within Maghazi. But nothing is sacrosanct. The gate bears evidence of an Israeli tank that broke through when the street outside was blocked with burning tires during the Intifada, and more recently the Palestinian National Authority expropriated a plot for “public works”—probably a school. Mohammed’s youngest brother, Tarik, uses the word “thief,” indicating what Barber has found to be a prevalent feeling among Gazans: that the Israeli occupation has only been replaced with another heavy hand—a newly imported power structure from Tunis that treats native Gazans as second-class citizens.

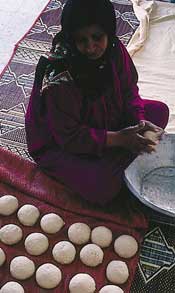

The men talk while Mohammed’s mother, a Bedouin woman, walks among the trees with her goats. As she watches the animals graze, her daughter Hadia and various daughters-in-law with their children join the group. Their presence speaks to the trust Barber has earned. He has arrived with strangers, and customarily the women do not show themselves among men they haven’t met. All of the women wear long gowns and the hijab, or head covering, an expression of modesty for Muslim women.

In the stillness of the late afternoon, shadows deepen on the trees and globed fruit. The shrouded matriarch with her goats and the eager, playful children lend the scene a timeless, archetypal quality. As the sun sets and we return to the house, Barber describes Gaza as a paradox: “It’s one of the most peaceful and most troubled places in the world.”