Miles

Miles

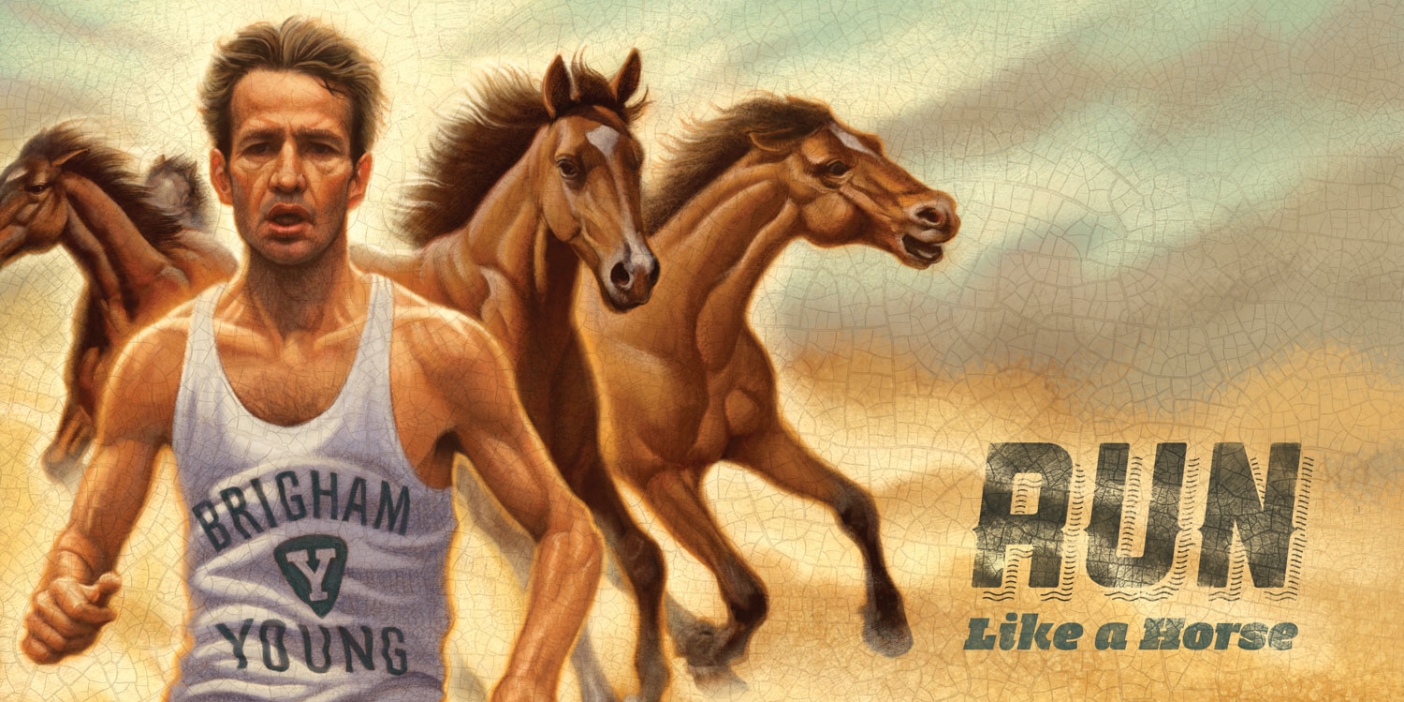

One step at a time, Miles Batty has lived up to his name—claiming records and championships and now making a run at the Olympics.

Miles B. Batty (’12) had just broken the collegiate indoor mile record, yet he felt lonelier than one shoe.

Batty’s historic run—a blazing time of 3:54.54 at the 2012 Millrose Games in New York City in February—was an impressive accomplishment, but he had no one with whom to celebrate it. For the first time in his career, he had traveled alone to an event, without teammates or coaches. “It was kind of a solitary experience,” he remembers.

Batty had lined up in lane one—on the inside—and started slowly, jockeying for position among five other collegians and six professionals in the Millrose Games’ Wanamaker Mile. As Batty found himself boxed in and trailing early on, he knew he needed to be patient. “I waited for things to open up,” he says. “I was watching for any opportunity to go. It was a little nerve-wracking.”

A third of the way into the race, Batty made his move, passing one runner, then another, passing some on the inside, others on the outside. Just before the final lap, he sprinted into second place behind professional runner Matthew Centrowitz Jr., the 2011 World Championship bronze medalist in the 1,500-meter, and followed him to the finish. As the winner, Centrowitz became the center of attention, taking a well-deserved victory lap.

Because Batty finished second, his NCAA record was met with relatively little fanfare in the Big Apple. Batty enjoyed his memorable accomplishment alone.

At the same time, however, thousands of miles away in a packed Seattle hotel room, pandemonium erupted.

Batty’s coach, Edward D. Eyestone (BS ’85, MS ’90), and his Cougar teammates had just completed a competition at the University of Washington. They rushed back to their hotel to watch Batty’s run via live streaming on laptop computers.

“Early on, the room was kind of quiet,” recalls Eyestone, who used his smartphone to record the team watching the race and later uploaded the video to YouTube. “But with each critical pass, the level of enthusiasm in the room grew and grew. The last lap was a fevered pitch. The phone got knocked out of my hand and ended up at the bottom of a dog pile. When the camera emerged, the guys were chanting his name like a bunch of maniacs.”

It’s hard to say which turned out to be more entertaining—Batty’s epic run, or his teammates’ rowdy, impromptu celebration.

“In retrospect,” says Eyestone. “I was as happy seeing it that way as if I would have gone and seen it live.”

A couple of days after the race, Batty watched the video.

“I was shocked,” he says. “You could feel the emotion in the room. It seemed they were more excited about it than I was. It was an awesome experience, probably one of the best experiences I’ve had at BYU—not necessarily that race, but being able to watch the reaction of my teammates and coach. That’s what it’s all about.”

“We’re all like brothers,” says Batty’s teammate and roommate Jared M. Rohatinsky (’13), who watched Batty’s record-breaking run in that Seattle hotel room. “We train with him, and when Miles was going for such a big goal, it was as if each of us were doing it along with him. It was a victory for all of us.”

Batty has given his teammates plenty to cheer about. He owns three school records—in the indoor mile, the anchor leg of the distance medley relay (DMR), and the outdoor 1,500-meter. He also boasts two national championships—in the indoor mile and the DMR—and he’s been an All-American twice in cross country and six times in track. He now has his sights set on representing the United States in the 1,500-meter, just shorter than the mile, at the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

“I’ve tried to keep my expectations high but realistic,” says Batty. “I don’t focus on what I’ve accomplished. One of my high school teammates only talked about the Olympics. My goal was to make the BYU traveling squad. Now, the Olympics are a realistic goal for me. But for him, he missed out on the short-term goals he needed to be accomplishing. I like to set goals within my reach. I’ve tried to stay one step ahead of myself.”

Step by Step

A Chinese proverb states that a journey of a thousand miles begins with one step. Well, Batty has certainly run thousands of miles, but his first steps on the journey were inauspicious. While he played various sports growing up, he didn’t start running seriously until high school. But his parents must have sensed something to name him Miles, which is actually a family name that dates back to the mid-1800s.

“It’s very ironic now,” Batty says. “As a kid in elementary school, there were the annoying name games. ‘How many miles can you run, Miles?’ Now, it actually works.”

In ninth grade Batty tried football but suffered a knee injury the first time he was tackled, essentially ending his football career.

“A friend was doing cross country,” Batty says. “He talked me into doing that.”

As a senior at Jordan High in Sandy, Utah, Batty was the 5A state champion in cross country, attracting Eyestone’s attention. “I saw Miles as a longer- distance guy,” Eyestone says. “He didn’t have a really super fast time in the mile. He wasn’t my blue chip of the year, not at all. I figured he’d be a utility infielder, so to speak.”

In many ways, Batty is an anomaly, taller and bigger than most middle-distance runners, with a 6-foot frame and a barrel chest. “He’s thicker than a lot of guys,” Eyestone says. “We’re used to seeing runners as bird-like creatures. He has an upright running motion that’s noticeable.”

Eyestone soon realized that Batty had significant potential. “We’re fortunate to find diamonds in the rough like Miles,” Eyestone says. At an NCAA regional meet at the end of his first year, Batty defeated three of his teammates in the 1,500-meter and narrowly missed going to nationals. “That’s when I figured I had something here,” Eyestone says.

But then Batty left BYU and running to serve a mission in Brazil, where, at one point, he had added 30 pounds to his frame. He wasn’t sure he would run again at the collegiate level.

“I like to set goals within my reach. I’ve tried to stay one step ahead of myself.”

“During my mission, I had a lot of doubts,” he says. “I was pudgy and overweight. I thought, ‘I’m never going to get back into shape and step foot on the track again in a BYU uniform.’ But that was O.K. It still would be worth it.”

When Batty returned, Eyestone was concerned at first. “I was running behind him on one of our runs,” he says. “I noticed that there seemed to be fat jiggling on his back.”

But it didn’t take long for Batty to shake off the mission rust.

“We’ve worked with missionaries since BYU’s been around, and I’ve been through it myself,” Eyestone says. “There’s a process to getting them back in shape. The best diet in the world is running 80 miles a week.”

Eyestone’s ability to empathize with Batty’s plight served as heaven-sent help.

“Most runners that have come through BYU have gone through similar situations,” Batty says. “It’s something that gives us all confidence. Otherwise we’d think it is a lost cause.”

If anyone can relate to Batty, it’s Eyestone, who starred at BYU in the 1980s after serving a mission. Eyestone captured four national championships at BYU and still owns school records in the indoor 3,000-meter and the outdoor 10,000-meter. Eyestone ended up as a 10-time All-American and a two-time Olympic marathoner.

Batty’s resume is shaping up to look similar; the two are among the best runners BYU has produced. “Coach Eyestone has accomplished great things,” Batty says. “He’s one of us.”

A Competitive Spirit

During his junior year, Batty knew he was close to breaking the vaunted four-minute mile. At a meet in Seattle, he barely missed his goal, running a 4:00.2. Even though he won the race by a massive 40 meters, set a new personal record, defeated several rivals, and qualified for nationals, he punched a wall in frustration after finishing the race.

“I knew where my training was at, and I felt I should have gone faster,” he says. At a subsequent meet in Seattle, Batty redeemed himself by running a 3:55.79, making him the fastest debut sub-four miler in U.S. collegiate history.

“It’s a great record,” Batty says. “It was a great feeling.”

“For Miles to take a whopping four seconds [off his time] when he finally broke four minutes was a big deal,” Eyestone says.

Batty’s mark also broke a 30-year-old school record set by two-time Olympian Douglas F. Padilla (BS ’83)—now an administrative assistant for the BYU track program—by more than a second. Batty became only the sixth Utah native to run a sub-four mile, and his time was the fastest of them all.

“Running comes down to mental toughness,” says Rohantinsky. “I think that’s why Miles is so good. He has this monster inside him that says, ‘I’m not going to let anybody beat me.’ When he’s in a race and he sees someone coming up alongside him, he puts his head down, he grits his teeth, and starts pumping his arms faster. You just know he’s going to do it.”

Then again, Batty is competitive in just about everything he does.

“It goes to bocce ball, bowling, golfing, and it extends to his running,” Rohatinsky says. “He’s the most competitive guy I know.”

Batty takes his studies as seriously as he does his races. His GPA, like his mile time, is just under a four, at 3.93. A double major in exercise science and neuroscience, Batty plans, after his running career is over, to attend medical school, where he would like to study sports medicine, orthopedics, and emergency medicine. To him, the ultimate academic recognition came in spring 2012, when he received the NCAA’s Walter Byers Postgraduate Scholarship, which offers $24,000 per year for graduate studies. “I was glad just to be nominated,” he says. “To win it was a great honor, and it was humbling.”

“People don’t understand what it takes to not only be a national champion and a collegiate record holder but to maintain a 3.9 GPA—[it] is just unheard of,” says Rohatinsky. “No matter what he’s doing, he wants to give 100 percent and be the best at it. He wants to take the hardest route, pick the hardest thing, and excel more than anyone else at it. He just wants to be the best he can be and not settle for anything less.”

Batty’s dad, Gary W. Batty (BS ’81, MAcc ’85), is equally proud of what his well-rounded son has done athletically and academically. “It’s really kind of a package,” he says. “It’s the combination of everything that Miles is and Miles does.” Around campus Batty has a reputation for being humble, gracious, and grounded as well as fun-loving, laid-back, and light-hearted. “He’s not the serious, scary jock that some other athletes are thought of being,” Rohatinsky says. “As a teammate, he’s a good, silent leader. Some guys—when they’re the best on the team, they make it known. Miles isn’t like that.”

Growing up, Batty liked backpacking trips and mountain biking. When he was in elementary school, his family lived in the small town of Pine, Ariz., where he and his brothers had an entire forest to explore. “We’d wander off and see what we could find,” Batty says. “We liked exploring, shooting BB guns, and building forts.”

Gary Batty says his son has always had a competitive nature, fostered in part by being the second of three boys. Miles was always competing against his older brother, Tyler (BS ’11), and his younger brother, Cameron. The three boys constantly played games and sports against each other and against other boys in the neighborhood; their basketball court was the dirt driveway, the backboard nailed to a pine tree.

“I looked up to my older brother and wanted to follow in his footsteps,” Batty says. “I wanted to have a 4.0 [in high school] because my brother had done it. A lot of stuff I’ve done has been following my brother.”

“Miles has always been determined, focused,” Gary Batty says. “In some ways, I’m not surprised by what Miles has done. In other ways, yeah, I’m surprised.”

A Double Championship

In the spring of 2011, Batty was scheduled to run both the mile and the distance medley relay at the NCAA indoor championships. That would require him to run the mile qualifying race on Friday afternoon, anchor the DMR on Friday night, and then compete in the mile championship on Saturday: three mile-long races in less than 24 hours.

“It was a lot to ask of him,” Eyestone recalls. “Miles was the only one attempting that. Nobody was crazy enough to do both. But I felt like he was strong enough to pull it off.”

Batty advanced to the final in the mile, then, hours later, was on the track for the DMR. He took the baton in first place but soon dropped into third, though it was all part of his strategy.

“When you’re leading, you’re acting as a pacer for everyone else and you’re hunted for the second half of the race,” Batty says. “I like being relaxed early on and saving up that energy to attack at the end.”

“There are fewer guys that have run [a mile] under four minutes than have climbed Mount Everest.”

With a little more than one lap remaining, Batty made his move, passing a pair of runners and cruising to victory, capping a brilliantly executed anchor leg.

“That race was ours to lose,” he says. “I didn’t want to let my teammates down.”

Going into that meet, Batty knew that some people were critical of him, saying he was giving up his shot at a national championship in the mile. After claiming the DMR title, Batty battled both fatigue and complacency in the next day’s mile championship. In a physical race that featured some jostling and pushing, Batty again waited to make his final charge. As Tulsa’s Chris O’Hare glanced over his shoulder, Batty, on a full sprint, passed him in the final 10 meters.

“In that last turn, I kept asking myself, ‘How bad do you want this?’” he says. “To get two championships in one meet was unbelievable. I never dreamed it could happen.” He recorded a sub-four mile in both of the championship races.

“He wanted to win both titles and to share that experience with his teammates,” Eyestone says. “He risked his individual national championship for a team national championship and he ended up getting them both.”

Those victories illustrate the way Batty uses his brain when he runs.

“He has extremely good race savvy in terms of placing himself, moving, and positioning,” Eyestone says. “As the race unfolds, there are times when he needs to move up and he senses that. He knows he has to be in certain positions at certain places during the race to have a chance to win or set a record. Some of it is a God-given talent. He’s developed also through experience.”

In 2012 Batty attempted to run both events again in the indoor championships. Though the results weren’t the same, he still made an impression. By the time Batty grasped the baton in the DMR, the Cougars were in seventh place, about four seconds behind the leader. Batty slowly closed the gap, catching up to the pack and then passing team after team in the final stretch to come in third, running his leg in under four minutes.

Physically spent from his heroics in the DMR, Batty also finished third in the mile the next day, running a 4:01 and crossing the finish line just two-tenths of a second behind the winner.

“His opportunity to win the national championship was compromised,” Eyestone says. “He was in the same position, with the same guy [O’Hare] as last year. This time the gear wasn’t quite there. I think it was because of the effort he had given the day before.”

Had Batty run the individual mile as fast as he ran in the team relay, he would have won the event by four seconds.

Olympic Dreams

One of the toughest exploits in sport is running a sub-four mile, which puts Batty in an elite class.

“It’s one of the most exclusive clubs, certainly,” Eyestone says of the sub-four milers. “There are fewer guys that have run under four minutes than have climbed Mount Everest.”

Still, Eyestone adds, running a mile under four minutes is becoming more commonplace. During the last indoor season, 23 NCAA runners accomplished the feat, meaning that earning a spot on the U.S. Olympic Team is a tall order.

“He’s going to have to beat Olympic and World Championship medalists just to make the U.S. team,” Eyestone says. “That’s not an easy row to hoe. But he’s run faster indoors than any other collegian. He’s the hungry collegian with a chance. I think he has a very good chance of making the Olympic team.”

But, as usual, Batty is not taking anything for granted.

“It’s the end-all goal, I think,” he says of the Olympics. “But there’s a lot that needs to be done before then. I can’t get too far ahead of myself. I focus on my next big race, my next big step. There are a lot of steps in the journey. I definitely try to focus on one thing at a time while keeping in mind the whole process.”

Now that his BYU career is over, Batty is looking to secure a professional sponsorship to enable him to continue competing on the track for as long as he can. As far as he’s concerned, medical school can wait.

“I don’t want to be done. I don’t think I’ve reached my full potential,” he says. “I’ve had to do all this while being in school. I want to make it a full-time gig and see what I’m capable of then. My plan is to run for two more years and [then] go to medical school. But if things are going great, I’m not going to stop. In four years, the Olympics are in Brazil, which is where I served my mission. But you can’t count on that. [The 2012 Olympics] could be my only shot.”

As always, Batty is taking one race at a time. One lap at a time. One step at a time.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.