The game of Scrabble offers some important life lessons.

Scrabble runs in the family. It began with my grandmother and passed to my mother and then to me. When I was young, we visited Grandma regularly and each visit involved as many Scrabble matches as necessary for her to win. She knew all the tricks: words with q but not u, like qanat, which I later studied as an engineer, and short words like aa, which once stumped me on a BYU geology exam.

She also knew some not-so-fair tricks. A pure Scrabble set contains only two blank tiles—freebies that can substitute for any letter—but Grandma sometimes added blanks from other sets or just flipped over a plain letter to make it appear blank. Playing with novices, she had the upper hand. But she never fooled anyone in my family, and we usually played along. I often recalled what a high school English teacher had taught me: “If you cheat, I may or may not know. But either way, may you burn in guilt forever.”

When I moved to Boston for graduate school, I met with a bishopric member to receive a new church calling.

“We’d like you to serve as Cubmaster,” the counselor said.

What? Cubmaster? I flashed back to my own Cub Scouting experience. My den leader crying in her kitchen as our bake-off turned to bedlam. Another leader hospitalized after a rope swing accident. Boys plastering Oreos on the cubmaster’s truck. Really? You’re asking me to risk my life every Wednesday night with a mess of intractable, half-uniformed 8-year-olds?

Now is a great time for a blank tile, I thought. Something to fill in the gaps and make meaning out of this mayhem. I reached into my mental Scrabble pouch but found no blank. I thought about Grandma. Should I fake some excuse? Like “I’m allergic to Cubs?” No. I’d burn in guilt forever.

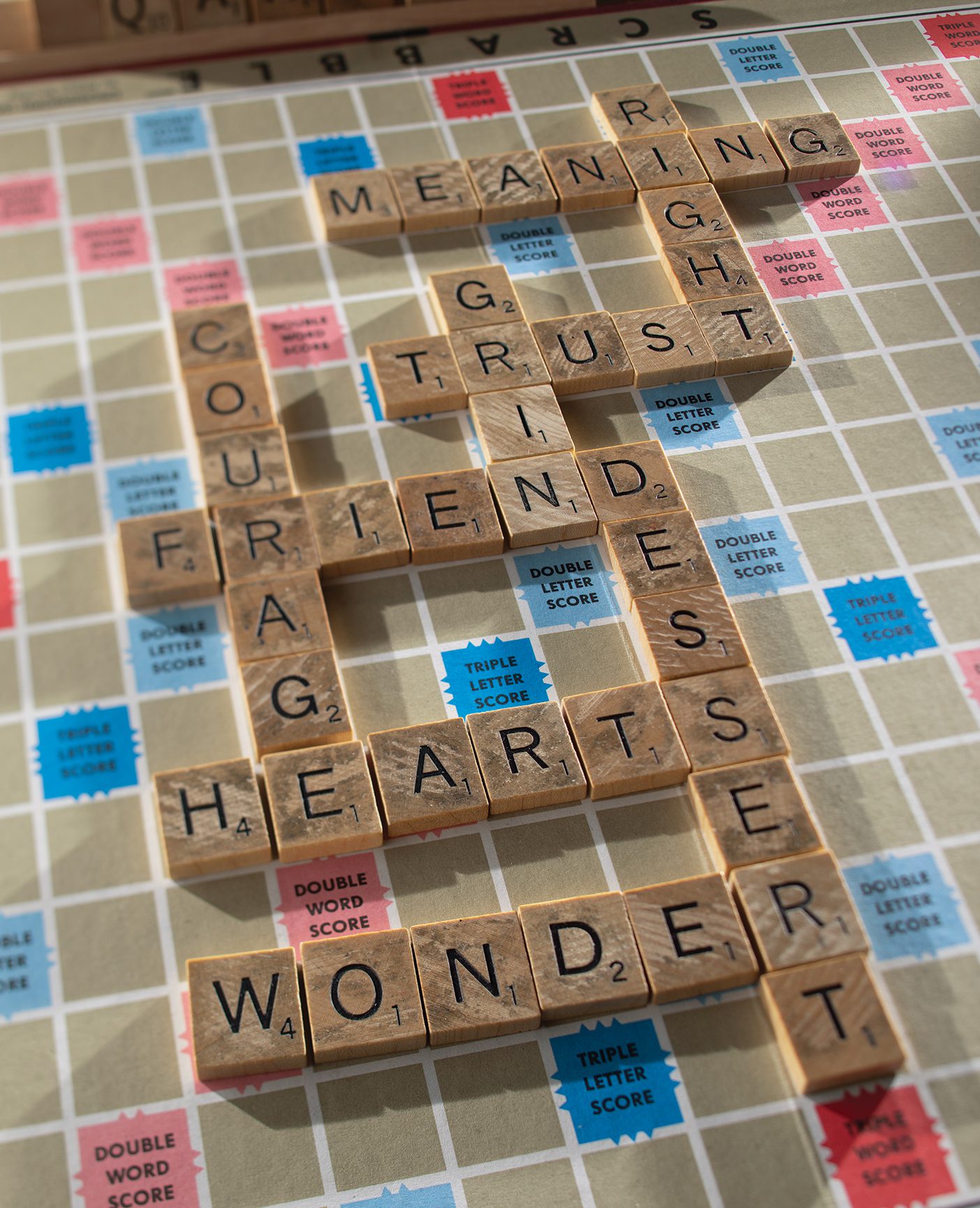

A Scrabble board transforms and gains meaning with each new letter. Sometimes it’s not so good. Grin turns to grind, right turns to fright, and sorrow becomes sorrows. Yet in the course of the game, end becomes friend, rust becomes trust, and age becomes courage. Only later do we appreciate the journey that shaped the outcome. Maybe my year as Cubmaster to those fatherless city kids wasn’t a mistake after all. Unlike Scrabble, life allows for multiple victors.

Scrabble is a language game where players arrange letters to create meaning—it’s the only way to earn points. But players draw the tiles blind. Some rejoice when blessed with valuable letters; others groan when they see their poor collection. It seems unfair.

We’ve all felt this way. It’s part of the human experience to deal with conditions beyond our control. Naturally we wish for an alternative. Even ancient prophets shared this sentiment. Alma conceded that “I ought to be content with the things which the Lord hath allotted unto me” (Alma 29:3), and Nephi was “consigned that these are my days” (Hel. 7:9).

Regardless of what letters we draw, we must still make sense of them. Somewhere on the board, we find pieces that help us make something meaningful—to find patterns, to explore possibilities, to grow. And there’s the irony: We can’t succeed with just our own tiles. It may be a competition, but we actually need the other players. We need their tiles, their contributions. We need them to create opportunities for us to make meaning, and they need us to do the same.

Yes, Scrabble runs in the family. I think of my grandparents. They played their part. And my parents play theirs, and my wife plays hers. I think of our special-needs daughter and our future family. Will I play my part? Will I leave enough words to help them fill an otherwise empty lifetime with meaning?

After countless games of Scrabble, I’ve learned a few good lessons.

When you see hater, think heart.

When life gives you a downer, turn it into wonder.

And when you get stressed, make some dessert.

Share a Family Story

In Letters from Home BYU Magazine publishes essays by alumni about family-life experiences—as parents, spouses, grandparents, children. Essays should be 700 words and written in first-person voice. BYU Magazine will pay $350 for essays published in Letters from Home. Send submissions to lettersfromhome@byu.edu.