By President Eric B. Shumway, ’64 One of the most significant episodes in our Savior’s mortal ministry is the raising of Lazarus from the dead after he had lain in the tomb for four days. It is an astounding public miracle that illuminates core truths about Christ and His Atonement.

In the story Christ receives desperate word from Martha and Mary to come to Bethany, for their brother is deathly ill. Jesus deliberately delays His journey for two days, then announces that Lazarus is dead and that He and His disciples must go to him.

When Christ arrives in Bethany, Martha greets Him with weeping and a gentle rebuke: “Lord, if thou hadst been here, my brother had not died” (John 11:21). Martha’s complaint is followed by her fervent testimony: “But I know, that even now, whatsoever thou wilt ask of God, God will give it thee” (v. 22). Jesus affirms His own role and identity: “I am the resurrection, and the life: he that believeth in me, though he were dead, yet shall he live” (v. 25).

The grieving of the sisters, the wailing of the mourners, Christ’s own tears, the hostility of certain ones in the crowd, and the melancholy of the grave site constitute a crescendo of human emotion. Jesus commands that the stone covering the tomb’s entrance be removed. Martha objects, saying, “Lord, by this time he stinketh: for he hath been dead four days” (v. 39). Christ says, “If thou wouldest believe, thou shouldest see the glory of God” (v. 40). The stone is removed, and Jesus offers a prayer of gratitude.

The climactic moment comes when Christ cries out in a loud voice, “Lazarus, come forth” (v. 43). Can you imagine the combination of hope, terror, and surprise the people feel when Lazarus obeys and rises, “bound hand and foot with graveclothes: and his face . . . bound about with a napkin” (v. 44)? The sight and smell of this dead man must have been more than some could bear. Then came Christ’s second command to certain others standing by: “Loose him, and let him go” (v. 44).

Christ was commanding the people to free Lazarus, to remove the graveclothes and unbind the wrappings from around his eyes, mouth, hands, and feet—the wrappings of the grave. For he lived again! Think of the joy! But can we imagine also the hesitancy of some to reach out and remove the graveclothes? No doubt some shrank away completely.

For me the Lazarus story provides one of the most powerful metaphors of the Atonement of Christ for all humankind. We are all like Lazarus, beloved of the Lord, but wrapped about in the graveclothes of this world.

These two commandments to “come forth” and to “loose him, and let him go” constitute the way and the power of the Atonement. Let me illustrate from the life of a BYU—Hawaii professor.

Katsuhiro (Kats) Kajiyama, ’67, was among the first Church College of Hawaii (later BYU—Hawaii) students to come from Japan. Now a professor of Japanese on our campus, he reminisced about his rescue, Lazarus-like, from soul death. His tomb was a dark hopelessness; his graveclothes a bitter cynicism and hatred toward Americans. As he said in the account he sent to me: “I lived numbly, desensitized, and cold.”

Of his early childhood, he especially remembers his mother—beautiful, soft, kind, gentle. His home in Hiroshima was a place of peace. On the morning of Aug. 6, 1945, 7-year-old Kats was playing with a friend at school. These are his words:

An extraordinarily bright flash of light exploded as if a thousand flash photos had been taken, the light enveloping the whole building and sky. . . . There was a thunderous blast and a gust of force so strong that it shook the entire building and ground. . . . All around me there were noises of things being crushed and of shattered glass cascading to the floor. Kats describes the panic that ensued. Covered with blood, he ran out into a world surreal in its horror: houses on fire, whirling dust and smoke, hysterical screaming from every direction. “Floating, groping along in the chaos,” he longed for his beautiful mother’s comfort, her soft, gentle touch. However, when he arrived home, he says:

I [encountered] a strange woman in baked, dirty clothes with a grotesquely swollen face and burnt, short, kinky hair. . . . Severe burns disfigured my beautiful mother into a stranger. . . . I looked on in disbelief as her sweet voice called my name, “Kacchan.” I cried for relief that it was she, but also [in terror for her dreadful look]. It took 20 agonizing days for her to die. His brother was never found.

Motherless and reduced to abject poverty, Kats was tormented by the images of the pain and death of his mother and brother. “It seemed that [he] would never find peace in this cruel and harsh existence,” until one day years later an American named Elder Gary L. Roper, ’60, spoke to him: “How is school? Do you live nearby? I see you often in the streetcar. Would you like to join an activity for young people?”

Kats says he was amazed by this American’s tender smile. “I was unfamiliar with this type of gentleness from foreigners. . . . Until then I had [believed] all Americans were heartless monsters who willingly sought to hurt and degrade the Japanese people.”

A year after his introduction to the Church, he was still reluctant to join. But at a district conference, the voice of Christ from the mouth of mission president Paul C. Andrus, ’50, commanded, “‘Come forth.’ Be baptized.”

In contrast to the horrific flash of light in the atomic bomb blast, Kats writes of his baptism: “At that moment . . . I felt as though the brightest sun had broken through the clouds and streamed through the building. The whole auditorium seemed to be brightly lit and glowing. I was . . . filled with incomprehensible happiness and joy.” The graveclothes of his tortured past were now unwrapped. The cynicism, hatred, and bitterness were gone.

Nearly every true conversion or repentance sequence is an analogue of the story of Lazarus.

But what if Lazarus, exercising his agency even as a spirit, had decided not to return to a decaying, tortured body? Or what if those present were squeamishly reluctant to touch the death wrappings of a man who clearly had been dead? Some people among us today would not be inclined to obey either commandment.

Sometimes the wrappings of death are manifest in the clothes of addiction and behavioral patterns that paralyze righteous thought and action, such as alcoholism, gambling, drug use, pornography, anger, and violence. These wrappings are made of coarse cloth and smell of hell, and they bind people in a tomb of hopeless illusion and despair.

But what about the death wrappings of a finer texture: the silken wrappings of pride and self-importance, of obsession with one’s appearance, of wealth devoid of any generous impulse? Many of these finer-textured addictions are mutations of things that satisfy basic needs; for example, the need we all have for encouragement morphing into a desperate search for praise and flattery.

The act of helping to remove someone’s “graveclothes,” as it were, is the essence of a Latter-day Saint’s errand from the Lord. You may ask yourself, “Am I an unbinder or am I a binder? Do I help remove the graveclothes of others, or do I wrap their graveclothes more tightly around them?”

Alma the Elder was, in effect, bound in heavy graveclothes. The act that unbound him was his willingness to listen to a prophet (see Mosiah 17). Abinadi gave his life to unbind Alma. In turn, Alma the Elder was an unbinder for his son, Alma the Younger, for whom all he could do was sincerely pray (see Mosiah 27:14). Prayer is part of the great unbinding process. Enos also found that out in his all-day-long prayer (see Enos 1).

Sister Shumway belongs to that vast army of unbinders in the Church whom we call Relief Society visiting teachers. For 10 years she has been a visiting teacher to a woman who has never once come to Church. During one visiting teaching session, Carolyn asked her if she ever read the Ensign magazine that she had sent her every month.

“No,” she said, pointing upward, “but I know Father in Heaven is there because you keep coming back and you do not judge me.”

This lady’s graveclothes are loosening. Her son became active and is now serving a mission in the Philippines.

I pray that the story of Lazarus will take root more deeply in all of us; that the power of the Atonement will give us courage to “come forth” and allow our graveclothes to be removed; and that we might be both the healers and the healed, the unbinders and the unbound.

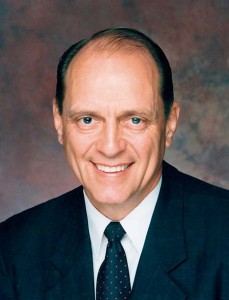

The complete text of this March 26, 2002, devotional address by Eric B. Shumway, president of BYU—Hawaii, is available at speeches.byu.edu/devo/2001-02/ShumwayW02.html.

LESSONS IN VIRTUE

Given the tremendous importance of . . . virtues now and in the world to come, should we be surprised if, to hasten the process, the Lord gives us, individually, the relevant and necessary clinical experiences? We do not usually seek these, however. Yet they seem to come, don’t they, even when we do not remember having signed up for a particular course? Sometimes we find ourselves enrolled again in the same course. Apparently we were only auditing before; perhaps this time it can be for credit! . . .

The Lord loves each of us too much to merely let us go on being what we now are, for he knows what we have the possibility to become!

—Elder Neal A. Maxwell, “In Him All Things Hold Together,” Fireside Address, March 31, 1991

WEB: The full text can be purchased at speeches.byu.edu/Detail.tpl?sku=0890A.