By Richard H. Cracroft

A few recent books offer fictional journeys and nonfictional sidetrips.

A good novel appeals to many of us because it is so downright entertaining and satisfying. Good fiction enables us to step outside of ourselves, take our bearings, and impose order on the chaos of life. It can carry us on others’ mortal journeys and expose us, vicariously, to imaginary, yet real, adventures, emotions, and tests of character—all at a comfortable remove, in an overstuffed chair, and within reach of a handful of salted nuts and an iced drink (7UP, of course!). In reading four recent novels by good writers—three of them BYU alumni—we undertake several satisfying imaginative journeys.

Douglas H. Thayer’s (BA ’55) new novel, The Tree House (Zarahemla Books; 373 pp.; $16.95), is the tale of Harris Thatcher’s harrowing journey from sheltered innocence in Provo to post-war Germany as a struggling but faithful Mormon missionary to Korea as an American G.I. who is shattered by the terror and tedium of the Korean Conflict and finally, wounded and broken, back home to Provo, where he experiences even further loss. At last, Harris’ sad mortal journey begins to wend upward to love, healing, and hope. In content, style, and tone, The Tree House recalls the stoical eloquence of Ernest Hemingway and becomes a kind of Mormon update of A Farewell to Arms. Like the grieving Lt. Frederic Henry, Corporal Harris Thatcher also exits the book limping and battle-scarred. But Harris is heading into a hopeful future on the arm of a bride who will love him into that future. As a Mormon missionary novel, The Tree House is better than anything we’ve had so far. As a story of soldiers-at-war, the novel captures the numbing terror of trench warfare in Korea with an immediacy that recalls Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage. The Tree House—Thayer’s third and best novel—is splendidly crafted stick-to-the-soul literature. Thayer, a professor of creative writing in his (record) 50th year of teaching at BYU, has also published two collections of short stories and a recent memoir, Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood.

Douglas H. Thayer’s (BA ’55) new novel, The Tree House (Zarahemla Books; 373 pp.; $16.95), is the tale of Harris Thatcher’s harrowing journey from sheltered innocence in Provo to post-war Germany as a struggling but faithful Mormon missionary to Korea as an American G.I. who is shattered by the terror and tedium of the Korean Conflict and finally, wounded and broken, back home to Provo, where he experiences even further loss. At last, Harris’ sad mortal journey begins to wend upward to love, healing, and hope. In content, style, and tone, The Tree House recalls the stoical eloquence of Ernest Hemingway and becomes a kind of Mormon update of A Farewell to Arms. Like the grieving Lt. Frederic Henry, Corporal Harris Thatcher also exits the book limping and battle-scarred. But Harris is heading into a hopeful future on the arm of a bride who will love him into that future. As a Mormon missionary novel, The Tree House is better than anything we’ve had so far. As a story of soldiers-at-war, the novel captures the numbing terror of trench warfare in Korea with an immediacy that recalls Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage. The Tree House—Thayer’s third and best novel—is splendidly crafted stick-to-the-soul literature. Thayer, a professor of creative writing in his (record) 50th year of teaching at BYU, has also published two collections of short stories and a recent memoir, Hooligan: A Mormon Boyhood.

Dean Hughes, who won our hearts with the Thomas family in the Children of the Promise and Hearts of the Children series, now returns to the saga to follow the fortunes of Diane in Promises to Keep: Diane’s Story (Deseret Book; 255 pp.; $17.95). Long divorced from her abusive husband, Diane is now a single parent in her mid-30s who is struggling to make a living, earn a graduate degree, avoid entangling relationships, and guide her bright, gorgeous, and headstrong 15-year-old daughter, Jenny, to happy adulthood. Complications ensue when Greg, her ex, interferes and very-good-prospect Spencer Holmes enters her life, lugging his own bag of complications. The novel shares Diane’s struggle to smooth the crinkles in her life. Hughes is a fine storyteller who teaches that timeless values are not always easily taught or learned, that faith trumps doubt, and that it is difficult to avoid the dizziness that sometimes overwhelms when one is keeping an eye single to the Lord, another eye peeled for the well-being of a teenager, and both eyes wide open to possibilities of breakdown, breakup, or breakthrough.

Dean Hughes, who won our hearts with the Thomas family in the Children of the Promise and Hearts of the Children series, now returns to the saga to follow the fortunes of Diane in Promises to Keep: Diane’s Story (Deseret Book; 255 pp.; $17.95). Long divorced from her abusive husband, Diane is now a single parent in her mid-30s who is struggling to make a living, earn a graduate degree, avoid entangling relationships, and guide her bright, gorgeous, and headstrong 15-year-old daughter, Jenny, to happy adulthood. Complications ensue when Greg, her ex, interferes and very-good-prospect Spencer Holmes enters her life, lugging his own bag of complications. The novel shares Diane’s struggle to smooth the crinkles in her life. Hughes is a fine storyteller who teaches that timeless values are not always easily taught or learned, that faith trumps doubt, and that it is difficult to avoid the dizziness that sometimes overwhelms when one is keeping an eye single to the Lord, another eye peeled for the well-being of a teenager, and both eyes wide open to possibilities of breakdown, breakup, or breakthrough.

Orson Scott Card (BA ’75), author of Ender’s Game (1985), Speaker for the Dead (1986), and the rest of the Ender saga, presents Ender in Exile (Tor; 380 pp.; $25.95), a sequel that is really a “mid-quel.” Card goes back in time (and space) to insert a story that takes place chronologically between Ender’s Game and Speaker for the Dead. Young world hero Andrew Wiggins (Ender the Xenocide), prevented from returning to Earth from Eros, becomes governor of a colony on Shakespeare, then an explorer on Ganges, a colony that is full of discoveries and danger. As Card explains in his afterword, getting the particulars of Ender in Exile to jibe with Ender’s Game, which he wrote more than 30 years ago, necessitated some changes in Card’s original story. So he did what any sci-fi revisionist historian would do: he rewrote chapter 15 of Ender’s Game and will publish the revision online and in all future editions of the book. Long live Ender Wiggins!

Orson Scott Card (BA ’75), author of Ender’s Game (1985), Speaker for the Dead (1986), and the rest of the Ender saga, presents Ender in Exile (Tor; 380 pp.; $25.95), a sequel that is really a “mid-quel.” Card goes back in time (and space) to insert a story that takes place chronologically between Ender’s Game and Speaker for the Dead. Young world hero Andrew Wiggins (Ender the Xenocide), prevented from returning to Earth from Eros, becomes governor of a colony on Shakespeare, then an explorer on Ganges, a colony that is full of discoveries and danger. As Card explains in his afterword, getting the particulars of Ender in Exile to jibe with Ender’s Game, which he wrote more than 30 years ago, necessitated some changes in Card’s original story. So he did what any sci-fi revisionist historian would do: he rewrote chapter 15 of Ender’s Game and will publish the revision online and in all future editions of the book. Long live Ender Wiggins!

Heather Brown Moore (BS ’94), in Abinadi (Covenant; 260 pp.; $16.95), spins a novel from the life and times of the Prophet Abinadi as recounted in the book of Mosiah. The author portrays Abinadi as a 24-year-old Nephite who is directed by the Lord to call King Noah and his fallen court to repentance. Moore’s Abinadi falls in love with and marries Raquel, daughter of Amulon, the apostate priest. Meanwhile, back at court, young Alma falls into wicked ways, becomes an apostate priest, and then, on hearing Abinadi’s witness, undergoes the conversion that will launch his rebellion against King Noah and transform him into a prophet of God. Moore, well known as the author of the four-volume Out of Jerusalem series based on the adventures of Lehi, Nephi, and company, has drawn richly on Book of Mormon and Mesoamerican scholarship to ground the imagined life and times of Abinadi and Alma in a welter of anthropological detail drawn from the Mayan civilization and the Book of Mormon account. The product is an exciting and faith-promoting tale—the Book of Mormon in 3-D and Technicolor.

Heather Brown Moore (BS ’94), in Abinadi (Covenant; 260 pp.; $16.95), spins a novel from the life and times of the Prophet Abinadi as recounted in the book of Mosiah. The author portrays Abinadi as a 24-year-old Nephite who is directed by the Lord to call King Noah and his fallen court to repentance. Moore’s Abinadi falls in love with and marries Raquel, daughter of Amulon, the apostate priest. Meanwhile, back at court, young Alma falls into wicked ways, becomes an apostate priest, and then, on hearing Abinadi’s witness, undergoes the conversion that will launch his rebellion against King Noah and transform him into a prophet of God. Moore, well known as the author of the four-volume Out of Jerusalem series based on the adventures of Lehi, Nephi, and company, has drawn richly on Book of Mormon and Mesoamerican scholarship to ground the imagined life and times of Abinadi and Alma in a welter of anthropological detail drawn from the Mayan civilization and the Book of Mormon account. The product is an exciting and faith-promoting tale—the Book of Mormon in 3-D and Technicolor.

Nonfiction, well told, also requires creativity, imagination, and literary finesse. Here are three nonfiction works on LDS history, the Doctrine and Covenants, and the temple, all by BYU alumni and faculty.

Brian K. (BS ’66) and Petrea Gillespie Kelly (BA ’66), compilers of Illustrated History of the Church (Covenant; 617 pp.; $39.95), originally wrote this LDS Church history as audio scripts. The result is a reader- and family-friendly history whose readability, attractive design, and numerous illustrations make this book ideal for reading aloud in family settings. The Kellys organize this big book around the administrations of the 16 Presidents of the Church, from Joseph Smith to Thomas S. Monson, and they color-code the 16 sections for easy reference. This solidly grounded, faithful history not only provides a fresh retelling of the familiar dramatic events of the Restoration, from New York to Utah, but also chronicles lesser-known struggles and triumphs of the Church in the later 19th century, its dynamic growth in the 20th century, and the even brighter prospects of the Church in the present international and temple-building era. The Kellys enrich each section with fresh stories and draw extensively on journals, memoirs, and letters to provide glimpses into the lives of the Latter-day Saints. This enjoyable history is further enhanced by dozens of historical sidebars describing concurrent regional, national, and world events as well as timelines and several hundred color and black-and-white images with informative captions.

Brian K. (BS ’66) and Petrea Gillespie Kelly (BA ’66), compilers of Illustrated History of the Church (Covenant; 617 pp.; $39.95), originally wrote this LDS Church history as audio scripts. The result is a reader- and family-friendly history whose readability, attractive design, and numerous illustrations make this book ideal for reading aloud in family settings. The Kellys organize this big book around the administrations of the 16 Presidents of the Church, from Joseph Smith to Thomas S. Monson, and they color-code the 16 sections for easy reference. This solidly grounded, faithful history not only provides a fresh retelling of the familiar dramatic events of the Restoration, from New York to Utah, but also chronicles lesser-known struggles and triumphs of the Church in the later 19th century, its dynamic growth in the 20th century, and the even brighter prospects of the Church in the present international and temple-building era. The Kellys enrich each section with fresh stories and draw extensively on journals, memoirs, and letters to provide glimpses into the lives of the Latter-day Saints. This enjoyable history is further enhanced by dozens of historical sidebars describing concurrent regional, national, and world events as well as timelines and several hundred color and black-and-white images with informative captions.

Steven C. Harper (BA ’94), in Making Sense of the Doctrine & Covenants: A Guided Tour Through Modern Revelations (Deseret Book; 601 pp.; $35.95), has written a commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants that underscores the unique nature of this modern scripture: It is the only scripture in which the reader is able to hear the voice of Jesus Christ speaking directly “unto all men”(D&C 1:2), as “I, the Lord”(D&C 1:5). It is the only scripture that is not a translation from an ancient language. It is the Lord’s handbook for the last dispensation, containing revelations that reveal, as one non-LDS scholar writes, “realms of doctrine unimagined in traditional Christian theology”(p. 13). Harper’s study eschews the usual verse-by-verse commentary and focuses, instead, on three inquiries about each section: 1) What are the historic origins and contexts of the revelation? 2) What is the content of the revelation? 3) What happened because of the revelation? Harper, an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU, makes no attempt to liken the revelations to modern readers; he leaves that to readers as they are directed by the Holy Spirit. He suggests, however, that a major doctrinal thread woven through the Doctrine and Covenants and very applicable to 21st-century readers is the principle of agency, “the power to choose whether to meet the Lord’s terms and receive his blessings—or not”(p. 16). He writes, “Locating agency in individuals is the doctrine and covenants of the book”(p. 15). The Doctrine and Covenants gradually unfolds the fundamental laws and doctrines of God and the covenants he enters into with Latter-day Saints.

Steven C. Harper (BA ’94), in Making Sense of the Doctrine & Covenants: A Guided Tour Through Modern Revelations (Deseret Book; 601 pp.; $35.95), has written a commentary on the Doctrine and Covenants that underscores the unique nature of this modern scripture: It is the only scripture in which the reader is able to hear the voice of Jesus Christ speaking directly “unto all men”(D&C 1:2), as “I, the Lord”(D&C 1:5). It is the only scripture that is not a translation from an ancient language. It is the Lord’s handbook for the last dispensation, containing revelations that reveal, as one non-LDS scholar writes, “realms of doctrine unimagined in traditional Christian theology”(p. 13). Harper’s study eschews the usual verse-by-verse commentary and focuses, instead, on three inquiries about each section: 1) What are the historic origins and contexts of the revelation? 2) What is the content of the revelation? 3) What happened because of the revelation? Harper, an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at BYU, makes no attempt to liken the revelations to modern readers; he leaves that to readers as they are directed by the Holy Spirit. He suggests, however, that a major doctrinal thread woven through the Doctrine and Covenants and very applicable to 21st-century readers is the principle of agency, “the power to choose whether to meet the Lord’s terms and receive his blessings—or not”(p. 16). He writes, “Locating agency in individuals is the doctrine and covenants of the book”(p. 15). The Doctrine and Covenants gradually unfolds the fundamental laws and doctrines of God and the covenants he enters into with Latter-day Saints.

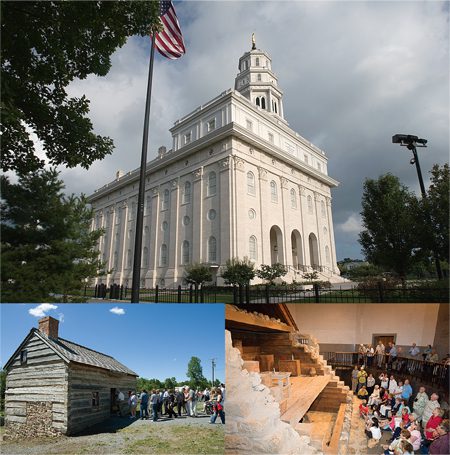

In The Temple: Where Heaven Meets Earth (Deseret Book; 193 pp.; $23.95), Truman G. Madsen, BYU professor of philosophy, emeritus, collects 10 discourses on Latter-day Saint temples and temple worship. Presenting insights gathered over a lifetime of study of the temple, Madsen urges readers to use “the house of God” as a spiritual guide toward “the perfect day”(D&C 50:24) and to use temple truths as impetus to “search deeper and deeper,” as Joseph Smith counseled, “into the mysteries of Godliness” (Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, sel. Joseph Fielding Smith [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972], p. 364). Drawing on the scriptures, Church history, doctrine, and personal experience, he suggests some of the symbolic richness of the temple ordinances and explores the purposes of the temple and the blessings to be found in temple worship. He helps temple worshipers, novice or seasoned, to understand that the House of the Lord is “a place designed for us to get [in Hugh Nibley’s words] ‘our bearings’ on the universe and our own lives” (p. 91).

In The Temple: Where Heaven Meets Earth (Deseret Book; 193 pp.; $23.95), Truman G. Madsen, BYU professor of philosophy, emeritus, collects 10 discourses on Latter-day Saint temples and temple worship. Presenting insights gathered over a lifetime of study of the temple, Madsen urges readers to use “the house of God” as a spiritual guide toward “the perfect day”(D&C 50:24) and to use temple truths as impetus to “search deeper and deeper,” as Joseph Smith counseled, “into the mysteries of Godliness” (Teachings of the Prophet Joseph Smith, sel. Joseph Fielding Smith [Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972], p. 364). Drawing on the scriptures, Church history, doctrine, and personal experience, he suggests some of the symbolic richness of the temple ordinances and explores the purposes of the temple and the blessings to be found in temple worship. He helps temple worshipers, novice or seasoned, to understand that the House of the Lord is “a place designed for us to get [in Hugh Nibley’s words] ‘our bearings’ on the universe and our own lives” (p. 91).

Richard H. Cracroft is BYU’s Nan Osmond Grass Professor in English, emeritus.