With discipline, wisdom, and a whole lot of hard work, Reese Hansen has led BYU’s law school for nearly half of its 31 years.

In warm summer evenings before dinner, the Hansen boys would play catch with their father, BYU law professor H. Reese Hansen. A father playing catch with his sons sounds laudable but not extraordinary, until you consider that Hansen played catch the way he does everything in life—hard.

“When I got older, the baseball was thrown harder,” recalls Dale T. Hansen, ’92. “He and I would stand 20 yards apart and throw the ball as hard as possible. His shoulder and my hand have never fully recovered. One of the old tree trunks at our house still bears the scars of one of his wild throws.”

Working hard has been a hallmark of Hansen’s career, which has led him from assistant dean to associate dean to dean of BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School. This summer, after 15 years as the top man in the dean’s office, Hansen will move to standard faculty quarters. At age 62, he has spent nearly half his life with dean appearing somewhere in his job title, and the law school has only experienced one year without Reese Hansen occupying a place in the deanery.

When Hansen, then just 32, first worked as assistant dean to then-dean Rex E. Lee, ’60, the infant law school had no alumni, just a dozen faculty members, and virtually no guarantee of success. Now, as Hansen leaves the deanship, the law school has an energetic group of 5,000 alumni and friends in the J. Reuben Clark Law Society; a full complement of 43 accomplished full-time faculty members, half of whom were hired by Hansen; and the distinction of being the youngest law school in the top 50, where the average institution age surpasses 100 years.

That a young law school at a religious university in a small state has achieved such prominence is due in no small part to Hansen’s hard work and effective leadership. Perhaps more than anything else, Hansen’s legacy as dean will be the simple principle that has guided his own life: work hard and opportunities will arise.

Small Town Values

Reese Hansen Prepares for his first day of Law School in 1969, the same day his oldest son began kindergarten. The work ethic Hansen learned as a boy in a rural community served him well in law school, where he excelled.

Only with a certain amount of prodding will Hansen speak about himself or the forces that shaped him, preferring to deflect the attention from himself.

“Isn’t life mostly accidental?” he asks whimsically. “It seems accidental.”

Turning more serious, Hansen credits his parents and his childhood environment.

“Being raised in a small agricultural community taught me to work hard,” he says. “I had parents who set expectations that were high and understood but not preached about.”

One of five children reared by Howard and Gayle Hansen in the rural community of Newton, in Cache County, Utah, Reese helped his father tend to their large garden and animals. Later, he spent summers working for his father at the Union Pacific Railroad.

Howard taught his son the kind of lessons that would cause a man to throw a baseball as hard as he could even when just playing a game of catch.

“He was a person who required the very best from you every time,” Hansen says of his father. “He was meticulous and exacting. He was a huge influence.”

While Howard Hansen was demanding, Gayle Hansen was equally forgiving. She was a person, Hansen says, who “you knew loved you no matter how bad a boy you were.”

Hansen stayed in Cache County to attend Utah State University, and he married his high school sweetheart after his sophomore year. By 1969 Reese and Kathryn Hansen had three young boys and a home in Bountiful, Utah. Five years after his USU graduation, Hansen had a position as Salt Lake City manager for Mountain States Telephone.

At that point the Hansens’ lives took a dramatic turn.

During an August 1969 drive home from Omaha, Neb., where Hansen’s father then held an executive position at Union Pacific headquarters, Reese and Kathryn decided that Reese should give up his job to study law at the University of Utah. Classes would begin in less than a month.

“I didn’t know anything about getting into law school,” Hansen told graduating University of Utah law students in a 2001 commencement speech, “and so I did what I have since learned everybody who wonders about law school does—I called the dean and made an appointment.”

Hansen convinced the law school dean to admit him to the 1969 entering class without taking the Law School Admissions Test (LSAT). Within a month of their cross-country drive, the Hansens had sold their Bountiful home and purchased a more affordable one, and Reese had started first-year law classes on the same day his oldest son, Brian, started kindergarten.

In law school Hansen spent 12 hours a day, often six days a week, at school. But Kathryn and their sons appreciated that he never brought his books home, and he never studied on Sunday.

“When he came home, he was ours,” Kathryn says. “It was not bad at all. I think we had learned by then that it’s hard work wherever you are.”

Perhaps in part because hard work was nothing new for him, Hansen excelled in law school. He earned a prestigious position as an editor of the University of Utah Law Review, but success had just as little luck in fazing Hansen as hard work.

“When he became the top student after our first year, a lot of us were scratching our heads, asking, ‘Who is Reese Hansen?’” recalls James H. Backman, Hansen’s classmate at the University of Utah College of Law and now his colleague on the BYU law faculty. “He was just so quiet. But we all came to know him well after that.”

Hansen wasn’t all work and no play. He formed lifelong friendships with classmates, including Backman, who joined the BYU faculty with Hansen in 1974, and Constance K. Lundberg, ’93, whom Hansen recruited to BYU and who now serves as associate dean and law librarian. Classmates also recall that Hansen effectively bridged the gap between returned Latter-day Saint missionary classmates and students with other interests, who were affectionately called “the lounge crowd.”

In Hansen’s third year of law school, the dean introduced him to a young Arizona lawyer who had come to Salt Lake City to seek the dean’s advice about starting a law school at BYU. At the time, Rex Lee, the founding dean of the J. Reuben Clark Law School, who would later become president of BYU, was just 36; Hansen was 30.

A Teaching Dean

Next to Hansen’s parents and his wife, the charismatic Lee would come to influence Hansen more than any other person. Upon graduating from law school, Hansen began practicing with a Salt Lake City firm, but Lee persuaded Hansen to work part-time as a legal-writing teaching assistant at the J. Reuben Clark Law School, where there were no upper-class law students for such positions in the inaugural year of 1973.

Hansen credits Lee with being a mentor, but perhaps more important, he was a friend.

“He was the one who took the chance to hire me,” Hansen says. “His influence in work and the gospel was huge.”

By fall 1974, Lee had convinced Hansen to give up his litigation practice altogether and join the BYU law faculty full-time as an assistant professor and assistant dean. Later, Lee would ask Hansen to serve as his counselor in a BYU stake presidency.

“They worked together seven days a week for years and years,” Kathryn Hansen says. “They jogged together nearly every noon hour. Reese admired Rex greatly.”

In 1976 Hansen assumed the title of associate dean. For years he oversaw law school admissions, and from 1982 to 1987 he was a member of the board of trustees of the Law School Admissions Council, a national organization that administers the LSAT. Elder Bruce C. Hafen, ’66, law school dean from 1985 to 1989 and now a member of the First Quorum of the Seventy for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, credits Hansen’s service on the council for helping to raise the profile and reputation of the J. Reuben Clark Law School on a national scale.

For 15 years Hansen was what Hafen calls “the key administrative advisor” to the law school’s first three deans, Lee, Carl S. Hawkins, and Hafen. “Everybody had to see what Reese thought,” Hafen says. “Everybody looked to him. He just had such great judgment that if Reese thought it, that would usually carry the day.”

Rex Lee, the BYU Law School’s founding dean, recruited Hansen to BYU in 1974 and Later asked him to serve as his counselor in a Stake Presidency. Hansen says Lee, who was president of BYU from 1989 to 1995, was both a mentor and a close friend.

Hansen also developed an expertise in the law of estate planning and distribution. He has authored and edited, with others, two editions of Cases and Text on the Law of Trusts.

Even when his duties as dean threatened to overtake his love of interacting with students, Hansen taught classes on wills, estates, and trusts. Kathryn credits her husband’s teaching responsibilities, along with service in branch presidencies at the Missionary Training Center (MTC), with invigorating him over the years.

“The dean should be in the classroom,” Hansen wrote in the Legal Education Symposium II in the University of Toledo Law Review in 2001. “In addition to missing the personal joy of the classroom and sharing teaching experiences with the faculty, I am convinced that not teaching on a regular basis compromises the dean’s leadership position.”

As a teacher Hansen possesses a mature perspective borne of experience and an even-keeled personality. Although the cases students read in his classes involve some highly unusual situations—such as a preacher orchestrating the murder of a wealthy parishioner to get her assets—Hansen makes it clear that nonsense is not to be tolerated in life or in his class.

At the conclusion of one recent semester, Hansen advised students preparing for his final exam not to give in to the temptation, so vexing to so many lawyers, to overwrite.

“It’s one of those exams where if you know the answer, you can say so in a sentence,” he said. “If you don’t know the answer, a paragraph won’t help you.”

Hansen also has a subtle way of fulfilling his teaching responsibilities while planting seeds in the subconscious minds of hundreds of future lawyers who might one day receive a fund-raising call from the dean: In virtually every example Hansen develops to illustrate legal concepts, the testator (the person who writes the will) gives his or her estate to the BYU law school.

Church, Family, and Health

In July 1989 Hansen slid into the dean’s office, on an interim basis, when Hafen became the provost for BYU’s newly installed president, Rex Lee. On a Thursday in March 1990, Hansen was named law school dean on a permanent basis, and on Sunday of the same week he was sustained as a stake president.

“He doesn’t have a lot of hobbies,” Kathryn Hansen says, explaining that her husband had little time left for much of anything after fulfilling his duties as dean, church leader, and father and husband. “There are not a lot of extra things in his life.”

Reese Hansen does have a penchant for John Wayne movies, and he can sometimes be found watching a ball game. At various times in his life, he has avidly participated in basketball, tennis, racquetball, and running. But his biggest pursuit outside of work and church callings is his family.

Dale Hansen cannot recall ever sitting in sacrament meeting with his father, but Reese Hansen always made time—usually late at night—to help his sons with their homework. Hansen required his children to meticulously walk through complicated math story problems, and “then he would take great pains to explain to us why we got the answer we did,” Dale says.

Hansen frequently engaged his sons in in-depth conversations, but he rarely if ever made conclusions or gave orders. “He does not impose his view on your strain of thought,” Dale says. “He will advise, but he will never tell you what to do. He wants you to make the decision.”

The Hansens didn’t make a point of pushing their sons toward professional degrees, but the family’s long and close association with university life apparently rubbed off, and all four sons received graduate degrees: Brian, ’87, and Dale are lawyers, Mark, ’89, is a doctor, and Curtis, ’97, is a certified public accountant.

“It was the environment they were in,” Hansen says. “We never sat down and said, ‘OK, Son, you’ve got to be thinking about graduate school.’ But we were at BYU, and they just assumed that’s what they wanted to do. It was one of the blessings of being here.”

One of the greatest challenges of Hansen’s life pitted him against a foe that threatened his continued association with his family and that could not succumb easily to his prodigious capacity for hard work. In 1992 doctors diagnosed a rare and aggressive form of cancer called fibrosarcoma in the tricep muscle of his right arm. He had surgery to remove part of the muscle and received radiation treatments.

“It gets your attention,” Hansen says. “You have an opportunity to reorder your priorities because it’s very scary. Confronting the prospect of dying early really changes the way you conduct your life.”

The surgery and treatment were effective, but the range of motion in Hansen’s arm became limited, and later injuries required more surgeries.

“It has been a challenge,” Kathryn says. “But he just worked through it. He’s just gone on. It all goes back to the work ethic—you just do what you have to do.”

Wisdom and Leadership

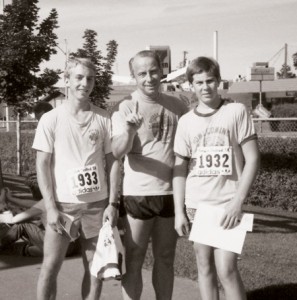

Hansen Celebrates with his sons Dale and Curtis after the 1985 Freedom Festival Race. A participant in various sports, Hansen actively supported his four sons in their athletic and academic endeavors.

Among many contributions to the success of the law school, the greatest accomplishment of Hansen’s tenure as dean might well be the hiring of faculty members. The faculty are of supreme importance to Hansen: they are his friends, but they also represent the product of his most important work.

“The faculty is the most important single component in building a successful law school,” Hansen wrote in the Leadership in Legal Education Symposium II. “It is . . . clear to me that it is worth whatever effort it takes to be sure that faculty hires are good ones. Unlike a student who will only be with you for three years, a faculty member is a permanent part of your life.”

Because the law school was determined to hire only the most extraordinarily qualified people, it wasn’t until the 1998–99 academic year, a full 25 years after the law school opened, that all the available faculty slots were filled.

“My belief is that you really have to work hard to hire people,” he says, “and then when you do hire them, you turn them loose to do the job you hired them to do.”

In contrast to the fears of some at the law school’s founding, there is a large pool of qualified lawyers interested in teaching at the J. Reuben Clark Law School. Hansen regularly converses with highly paid and successful lawyers around the country who say they would never leave their lucrative practices except to teach at BYU.

Those who work with Hansen cite his loyalty as one of his most distinguishing characteristics. Law librarian colleagues at other schools frequently tell Lundberg how lucky she is to work for Hansen because he has taken such a keen interest in the library. He worked diligently to secure $11 million in donations to renovate the Howard W. Hunter Law Library in 1997.

“If he commits to someone, he commits 100 percent,” Lundberg says. “If you work for him, he will do anything to make your life better and your work better.”

Hansen also directed fund-raising efforts to endow professorships, scholarships, and a student-loan program. He built a sense of community and a tradition of loyalty around the law school by building up the J. Reuben Clark Law Society, which includes many influential lawyers, judges, and professors, both alumni and nonalumni.

Hansen also made friends for the J. Reuben Clark Law School while serving on the Membership Review Committee of the Association of American Law Schools and as founding chair of the Section for Deans at the American Bar Association.

Another quality that has served Hansen well in his various roles and assignments is an ability to see solutions to problems.

“I can’t tell you the number of times in the last 35 years that I have seen him walk into a dispute, see past the immediate emotion, and understand what’s really going on,” Lundberg says. “The name for that is wisdom.”

The BYU Dream

To visit Hansen’s plainly adorned second-floor office in the J. Reuben Clark Building is to glimpse his equally unpretentious character. True to Hansen’s modest nature, little in the office draws attention to itself.

A small bobblehead doll in the likeness of Supreme Court Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist presides over a simple desk and two chairs for visitors. Behind Hansen’s own chair are emblems of the three universities with which he has been associated most of his adult life: a Utah State University Aggies water bottle sits on a credenza next to a statuette of a cougar, and just above hangs a painting of an obviously satisfied cougar with part of a red “U” feather protruding from its thinly grinning mouth.

From this unostentatious but not uninviting office, Hansen guided one of the most unusual institutions in American legal education for half its three decades. When Hansen reviews the rankings—the law school is number 31 in the latest U.S. News & World Report list—he does so not to boast but to provide evidence of the true vision of those who believed that an upper-tier law school could flourish at a place like BYU.

Kathryn and Reese Hansen attended high school together in Cache Valley and married when Reese was a student at Utah State. For the last 30 years, though, they have lived in Utah Valley, where Reese has devoted his professional life to helping BYU’s Law School succeed.

“I think it’s fair to say the law school has turned out better than anyone would have dared imagine in 1973,” he says. “The recognition of the law school as one of the really good law schools in the country is gratifying.”

Hansen heard the naysayers in the early 1970s who doubted that a respected law school could be established at a university with ties as strong as those of BYU to the Church. He chose to believe.

“The reality is our relationship to the Church was and is our greatest asset,” he says, recalling that early faculty members had no other reason to leave tenured positions at prestigious schools to come to Provo.

Hafen witnessed Hansen’s commitment to BYU and the law school when they faced a particularly difficult administrative problem while Hafen was provost and Hansen was law school dean.

“He said there are some people who are not so sure the BYU dream really works,” Hafen recalls, referring to the balancing of academics and faith. “He spoke with a sort of passion to me: ‘I’ve given my life to the proposition that, yes, you can be loyal to all of those things. It does work.’

“I think I realized,” Hafen continues, “that one of the reasons it worked is because there would be someone like Reese Hansen to make it work.”

Ed Carter, a 2003 graduate of the J. Reuben Clark Law School, is completing a clerkship with Judge Ruggero J. Aldisert of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.