Literally and figuratively, Jumana Amer Salti has come a long way to play basketball at BYU. Of course, she isn’t your typical BYU basketball player. Yet when you consider the thousands of miles she has traveled and the scores of serendipitous events that have led her to Provo, she begins to look like a natural in a BYU uniform.

Right now, though, she’s sitting at the end of the bench. It’s a Saturday afternoon at the Marriott Center, and with 14 minutes remaining in the first half, the BYU women’s basketball team is losing by 10 points to heavily favored University of Portland. Salti, a redshirt freshman from Amman, Jordan, is leaning forward slightly, eagerly awaiting her turn. Finally, Cougar coach Soni Adams summons her 6-foot-2-inch backup center into the action. As Salti takes the floor, she quickly adjusts the white scrunchee that holds her dark ponytail in place. Almost as quickly, she adjusts the overall complexion of the contest.

Portland has taken command, but Salti’s aggressive style of play commands attention. Within 20 seconds of checking in, Salti picks up her first foul. Less than one minute later, she scores a layup off a nifty entry pass. Ten seconds after that, she forces her opponent into a turnover. Fifty ticks later, Salti glides down court on a fast break, receives a pass, misses a layup, but follows her miss and scores. With that, the Cougars cut the deficit to just five points. Then she forces a Portland player into an errant pass. She alters an opponent’s shot and, in the same sequence, blocks another. Not long after that, she is whistled for setting an illegal screen. Nothing like adding a pinch of Salti to spice up a game.

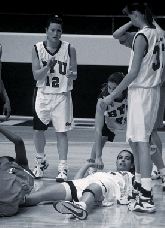

During a ten-minute stretch in the second half, Salti–she of the eclectic number double zero on her uniform– shoots an air ball, stands practically flat-footed to block another shot (the ball never even leaves the shooter’s hands), and leaps and crashes down hard on the floor as she fights for a loose ball. As a result of her fall, Salti’s arm is bleeding, and she leaves the game. Heading to the bench, she ex-changes high fives with her teammates and coaches. The sparse crowd acknowledges her effort, momentarily forgetting that the home team is trailing by 25 points. She flashes a 200-watt smile that lights up the Marriott Center.

The scene begs a question. How in the world does a nice, non-LDS, Jordanian girl like Jumana Salti (pronounced Ju-mah-nuh Sahl-tee), the daughter of an American mother and a Palestinian father, wind up playing basketball at an LDS school like BYU? Well, it helps that she possesses a good turnaround jump shot, a knack for rebounding, and well-above-average height.

Perhaps more important, however, is the fact that her parents are BYU graduates and that she has had two former BYU presidents, a princess, some newspaper clippings, some LDS Church representatives in Jordan, a little bit of luck–and a lot of destiny–on her side.

Jumana Salti is the Michael Jordan of Jordan. Of course, that’s the equivalent of being the Wayne Gretzky of Greece. Or the Ty Detmer of Thailand. Still, Salti, who took women’s basketball to another level in Jordan, is proving she can play American basketball at BYU. In fact, she is one of the few Jordanian athletes ever to compete at the NCAA’s Division I level in any sport.

Having grown up in a country that is populated by about 4 million people and has exactly two regulation hardwood basketball courts (one of which happened to be at her high school), Salti became the star of the first Jordanian women’s national team in 12 years. In 1996, she was voted by Jordanian sports editors as “Best Woman Basketball Player in Jordan.”

“She’s well-known here,” says Jumana’s mother, Rebecca, who has lived in Jordan for nearly 22 years. “She is very beloved by the girls she played with. She is very much missed in Jordan, and the people here are proud of her. People we don’t even know ask me how she is doing in America. She’s captured their imaginations.”

The Kingdom of Jordan, slightly larger in area than Indiana, is surrounded by Israel and the West Bank on the west, Saudi Arabia on the south, Iraq on the east, and Syria on the north. Because of the cauldron of cultures and ideologies boiling in the Middle East, the region represents one of the hottest hotbeds of social unrest on the planet as Arabs and Israelis, amid decades of conflict, try to co-exist. Compared to the country’s economic and political concerns, basketball ranks very low on the national scale of importance in Jordan. “Over 60 percent of the people here are Palestinian refugees,” Rebecca says. “The country puts its energy into getting people housed, fed, and clothed.”

As the daughter of well-to-do parents, Jumana put her energy into sports. Soccer is the most popular sport in Jordan, although basketball is catching up. For Jumana, basketball has long been more than just a pastime. It has been a way of life. “I took it to heart,” she explains. “Going to college in the United States was a goal for me. Other girls in Jordan played for fun. For them, it was just a hobby. There were no incentives to play other than it’s fun. They didn’t sacrifice as much as I do. I practiced harder.”

In high school, Salti would be in class until 2:15, practice until 4:30, go home to grab something to eat, and then practice from 5 until 7 p.m. with her club team. After that, she would lift weights for an hour, study, and then go to bed. On weekends, she had her games.

Starting with the third grade, she began attending the American Community School, a private institution for the children of expatriate and Jordanian families. When it came to sports, particularly basketball, she dominated.

By 1995, Jumana was part of the first Arab women’s team invited to an Olympic qualifying tournament. Although the upstarts from Jordan wound up winning just one of its six games (it won its final contest, against Indonesia), Salti, who averaged 20 points a game, was named to the tournament’s five-member All-Star team. “That experience told me I could play in the States,” Jumana says. “It was my first time against good competition.”

Yet the real triumph of the experience was that the team got there at all. Although the Jordanians were sponsored by several companies in Jordan, just days before the tournament began, the team still lacked about $5,000 needed for the trip to Japan. Fortuitously, the English-language newspaper in Amman detailed the team’s plight. One person who read about it was Princess Sarvath, the wife of Jordan’s Crown Prince Hassan, whose brother, King Hussein, is the head of state in Jordan. Apparently touched by the team’s desperate need, the princess donated the money necessary to send the Jordanians to the Orient. The team arrived two hours after the opening ceremonies began.

The news reports about Salti and her team captured the attention of others as well. As a result, little did she know, Jumana was forming her own little link to BYU.

During a visit in July 1994, then-BYU president Rex Lee toured Jordan and heard about this potential recruit whose parents had attended BYU in the 1960s. During that visit, President Lee met Amer and Rebecca Salti and invited Jumana to BYU. Not long after that, he wrote a letter to Jeanie Wilson, who was BYU’s head coach. When Adams took over the BYU women’s basketball program in 1994, she inherited the letter. “When the president speaks, you’d better take a look,” Adams says. After the Asia tournament in 1995, an LDS couple from Utah, Richard and Donna Butler, who are BYU alums and were serving in Jordan as representatives of the Church, also wrote Adams and sent her an impressive pile of newspaper clippings about Jumana.

“We knew she had to be kind of good,” Adams says. “We’re always looking for the best players. You look at the top programs around the country, men’s and women’s, and they have foreign players. For us, the BYU alumni help find us find good players. Since most of them aren’t experts at evaluating talent, you rarely know what you’re going to get. But we try to follow up the best we can.”

Consequently, Adams wrote a letter to Jumana and invited her to BYU to try out for the team, although Adams didn’t have a basketball scholarship for her. Salti decided to turn down her acceptance to Syracuse University (Salti never had had any contact with basketball coaches there) and came to Provo.

That tryout in the fall of 1995 was the first time Adams had ever seen Jumana (whose name means “pearl”). And Adams knew right off she had found a pearl. “It was really a blind try-out,” Adams remembers. “There were no tapes of her available. Her athleticism jumped out at us and we were kind of smiling after we saw her. It wasn’t until I met her that I realized she was 6-foot-2. If I would have known, I probably would have pursued her a little harder. We were lucky.”

As it turns out, Jumana considers herself lucky as well. “She was looking at the east of America,” Rebecca says of her daughter’s initial interest in Syracuse and other East-Coast schools. “Provo was the wrong direction. Destiny had something else for her.” Maybe destiny did lead her to BYU.

In 1960, Rebecca Buchanan was a young freshman from Missouri living in Helaman Halls. During her first week at BYU, she met a freshman from the Middle East named Amer Salti. “I was interested that he was a Palestinian,” Rebecca recalls. “We used to talk over lunch about his people.”

Amer was a bright student who was eager to learn and grateful to be in America. He had arrived in Provo via the Arab Development Society in Jericho. Amer had studied at a school founded by Musa Alami, who had established a Boy’s Town of sorts on the West Bank. While attempting to reclaim land in the Jordan Valley, Alami started the school to educate young men and prepare them for college. For 10 years, Amer studied under Alami.

Alami had visited the United States on numerous occasions and had met then-LDS Church President David O. McKay. President McKay in turn introduced Alami to BYU president Ernest L. Wilkinson, who later visited the project on the West Bank. It was President Wilkinson who personally invited Amer to further his education at BYU.

Alami had prepared Amer to go to school in the United States, so when the time came, Alami, who was fond of the Mormons, encouraged Amer to accept President Wilkinson’s offer. “Musa knew that there were warm, genuine people at BYU who would take good care of Amer,” Rebecca says. “Mormons are similar to Muslims. Both are very generous people. The Mormons were good to my husband at BYU. Amer was a happy student, happy to be at BYU. He took advantage of everything the school had to offer. He learned about Mormonism. He took music and dancing classes. He studied hard.”

Meanwhile, Amer and Rebecca’s friendship gradually bloomed, and a six-year courtship resulted in marriage in 1966. Both graduated from BYU (Amer also received his master’s degree from the school), and then the Saltis delved into their postgraduate education at various schools around the country and around the world. In 1975, they moved to Jordan.

(Today, Amer is deputy general manager of a major bank in Amman. Rebecca works for the Royal Society for the Conservation of Nature, managing projects for Bedouin and villagers who live in nature reserves. Both Amer and Rebecca are prominent, influential citizens in Jordan.) It was in Jordan that Rebecca and Amer raised their two daughters, Soraya and Jumana. Jumana, who was born in Amman in 1977, grew up playing sports. “People got a kick out of her,” Rebecca says. “There were three boys who lived next door who were rough, tough, and older. Jumana went there to play. She would come home crying and then go back and play some more. I think that made her strong.”

At age five, Jumana began participating in Jordanian little leagues, which were organized by transplanted Americans who live in Jordan. Jumana proved to be an outstanding all-around athlete. “She was the best soccer player, boy or girl, and was a great volleyball player,” Amer explains. “But she loved basketball the most.”

Amer, who stands 6-foot-2-inches, is quite an athlete himself. And it was he who provided the biggest boost to Jumana’s basketball career, although unwittingly. As a banker, he helped finance the $1.7 million gymnasium at the American Community School. It became the nation’s first hardwood basketball court. At the time, Amer could not have fathomed the role that gym would play in Jumana’s life.

As she grew, Jumana played for her high school team as well as the Jazira Club team and steadily improved. She visited summer basketball camps in the United States to receive instruction from American college coaches at Utah, North Carolina, and Stanford. “I came in as raw as can be, but I learned a lot,” she says.

Because of her mother, Jumana was already intimately acquainted with the United States long before she went to those camps. She spoke English as well as Arabic. “Jumana grew up belonging to two communities: Jordan and the United States,” Rebecca says. “I think that helped her become mature at a young age.” When she was 13, two days before the Gulf War began in January 1991, Jumana was put on a plane to Salt Lake City to live with her LDS grandmother, Virginia Bennion Buchanan. Jumana’s sister, Soraya, was already living with Virginia at the time and was a student at the University of Utah. (Soraya played volleyball briefly for the Utes.) “I remember it was very hectic, a very scary situation,” Jumana says about Jordan during the Gulf War. “No one really knew what would happen to Jordan.”

Six months later, Jumana returned to her homeland. By the time she finished high school, she was faced with the decision of what college to attend. Initially, BYU wasn’t at the top of her list. “I never expected to be coming here,” Jumana says now.

“She was reluctant at first,” Amer says. “She wasn’t sure she wanted to go where we went. But we kept persisting.”

In the end, Jumana decided Provo was the place for her, although it hasn’t always been easy to be a foreign student-athlete at BYU. According to Jumana, there are only 50 Arab students at BYU, although they have formed a close-knit family. Some of them attend Jumana’s games.

W hile Jumana grew up a Muslim, she has always been familiar with the LDS Church. Yet living in a Mormon society has been challenging. It has also been rewarding. “I expected a lot worse,” she says. “The people here have been so nice. It’s been great. I love the atmosphere. I didn’t think I’d like it before I came because I knew it would be so strict. But I’m glad I came.”

Amer and Rebecca are glad, too. “Best of all is the basketball team,” Amer says of Jumana’s experience at BYU. “That’s made the whole difference.” It’s clear Jumana enjoys playing with her teammates (who have nicknamed her “Jo”), and the feeling is mutual. “She is a great addition to our team,” Adams says. “She has leadership qualities and her smile lights up the room. She’s lovable. The players really like her.”

Jumana says she feels more comfortable all the time at BYU–not only with the atmosphere, but also with basketball. Last season, Jumana opted for a redshirt year in order to make the transition from international basketball to American basketball. After all, Jumana had never played with a U.S. women’s basketball, which is slightly smaller than the ball she had been used to in Jordan. She also had to get used to American rules, which are somewhat different from international rules.

Upon arriving at BYU, Jumana admits, confidence was her biggest nemesis. Instead of being the center of attention, like she was in Jordan, she felt like just another player. “I thought everyone was better than me because I’m from Jordan,” she says.

This year, her attitude has changed. Not only does Jumana have a basketball scholarship, she knows she belongs in women’s college basketball. “Playing time will give her more confidence,” Adams says. “I am trying to bring her along gently, trying to get her minutes. She’s playing against much better basketball competition than what she had been up against in Jordan. She will have an impact on this program. How much remains to be seen. She is our center of the future.”

As for her future, Jumana eventually wants to go to law school or earn a master’s degree and, like her parents, return to Jordan and work. In Jumana’s mind, it’s doubtful Jordan will ever have a team that will compete at the Olympic level.

For now, though, Jumana is wishing her parents could watch her play. “My dad has always been like my coach,” she says. “He came to every game since I was in the second grade. And if it wasn’t for my mom, I wouldn’t be playing, either. She sacrificed a lot to drive me to practices. I had time to go to school and concentrate on basketball.”

Amer and Rebecca visited Jumana at BYU last fall for a few weeks, but not long enough to see her play in a game. Now, she talks to her parents on the telephone about every ten days, speaking in either English or Arabic–or both in the same sentence. Of course, she gives them updates on her games. “I tell them everything that happens,” she says. “That is the best support system ever.” She also has her grandmother, who drives down from Salt Lake City to watch her play.

At BYU, thoughts of her parents aren’t far from her mind. “It’s kind of weird. I see Arab guys here on campus,” Jumana says, “and I can imagine how my dad was when he went to school here.”

Nine time zones away, back in Jordan, Amer and Rebecca are happy their daughter has found a home at the same place they met 35 years ago. “We wish we could travel in a conduit of light to watch her play,” Rebecca says. “The fun for us is she is doing her dream. A lot of effort has gone to helping her do that. We’re grateful for all of the people who have helped her.”

Among those Jumana could thank are a princess, several journalists, two LDS Church representatives, and a pair of late BYU presidents.

Indeed, Jumana Amer Salti must have been destined to play basketball at BYU.

Jeff Call, a 1994 graduate of BYU, is an editor of Cougar Sports Magazine.