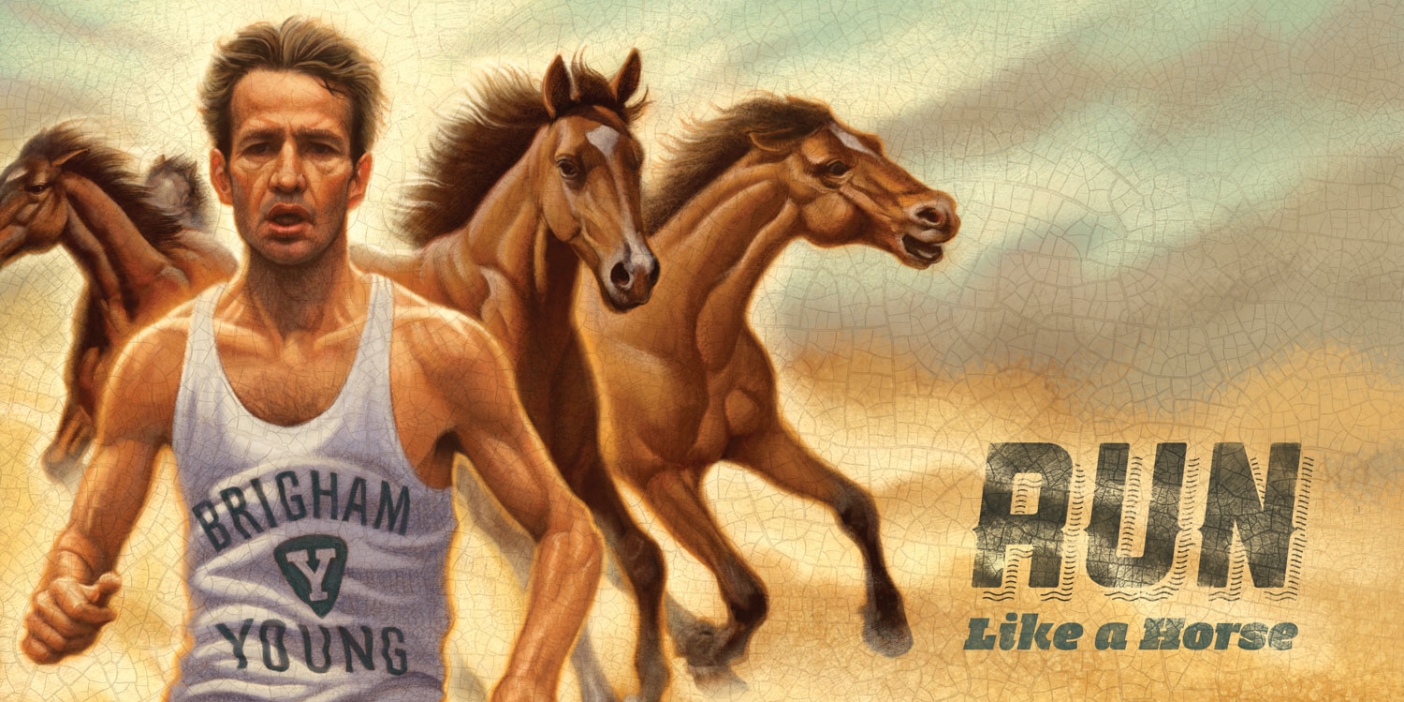

Recipient of a BYU Honored Alumni Award, a former athlete and communications star has been chasing dreams her whole life.

Recipient of a BYU Honored Alumni Award, a former athlete and communications star has been chasing dreams her whole life.

I did many things in my life that my parents didn’t approve of,” says María Guadalupe “Pitty” García Cardiell (BA ’81, MA ’91). Paradoxically, it was the lessons learned from her parents as a child in Toluca, Mexico—“Do your best, try your best, pursue an education”—that led García Cardiell to defy their wishes. “But later on, they were happy with my choices.”

It wasn’t any indiscretion that worried her parents and four brothers. Rather, it was her dogged pursuit of dreams that ran counter to cultural and familial expectations—from becoming a competitive runner as a girl to attending a university abroad to her eventual marriage choice. Despite her family’s disapproval, García Cardiell worked to keep her family close. She succeeded: When her parents visited BYU years later, she recalls, “they wept as they arrived in Provo.” When García Cardiell asked why, they said, “Because this city and university shaped you in so many nice ways.”

Though an excellent student in junior high in the early 1970s, the nearsighted García Cardiell struggled with her PE grades because her teacher gave points for making baskets. So she asked her teacher, “Why don’t you let us run and decide our grade by running?” He told her, “Next class I will run with you, and if you beat me we will think about it.” So they ran, and she won the race—and his encouragement to compete.

But when she asked her parents if she could race, García Cardiell recalls, “They said, ‘No way. It’s not acceptable for a girl to do that.’” Parentally approved or not, García Cardiell competed. “It was in me to run,” she explains. “I’d come home with a medal, and they’d say, ‘What’s that?’ and I’d say, ‘I took first place.’”

Her father, unhappy with Pitty’s disobedience and unsure of where track was taking her, began attending her practices. She pleaded, “Dad, you have to trust me!” and worked extra hard at school to please her parents. In time they relented, and by the age of 15, she had made it to the 100- and 200-meter finals at nationals, where she was disqualified in the 100 for jumping the gun. A year later, more determined than ever, she took first in the same events in the 16–18 age bracket.

Mexican colleges took notice, and several offered García Cardiell a scholarship. “But they were more interested in my running than in my education,” she says. “I wanted a real education and career.”

Gustavo Ibarra (MA ’76, PhD ’82), a Mexican national who attended grad school at BYU and became an assistant track coach, told BYU coaches Nena Rey Hawkes (MS ’65) and Clarence F. Robison (BS ’50) about the speedy sprinter from Toluca. On a visit to Mexico in April 1976, Robison watched García Cardiell practice. Impressed, he offered her a scholarship on the spot—one of the first full-ride scholarships BYU had ever offered an international athlete. But García Cardiell’s father was skeptical of the offer and didn’t like the idea of his only daughter leaving the country. But, despite not knowing English, García Cardiell was determined to go. When a yellow registration packet arrived in the mail, her father tentatively agreed, thinking homesickness would return her to him in a year. He was wrong.

At BYU García Cardiell hit the track running, setting records and performing at ever-higher levels. But learning English was hard, she had to adapt to a new culture as a Catholic at BYU, her advertising program was challenging, and homesickness took its toll. New friends came to her rescue. “I could write a book about the many people from BYU who helped me—even my coach, Coach Hawkes, who became like a mother to me,” she says. Professors worked with and encouraged her, and a few good friends supported her through a time of acute want when a massive devaluation of the peso made any money her parents sent valueless.

“I could write a book about the many people from BYU who helped me.” —Pitty García Cardiell

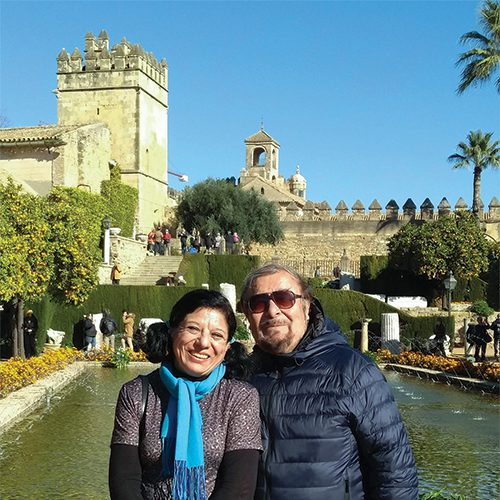

Amid success on the track and in the classroom, García Cardiell also found love during her college years. Though she was initially interested in an American BYU student, her Mexican friend Guillermo “Memo” Alfonso García Santín (MS ’91), a blind shot-putter she’d met during competitions, finally won her heart with his concern, intelligence, and good humor. But matrimony was categorically more important than other choices she’d made before—and her parents were resolute that she not marry a man with a disability.

“My heart was sad and heavy,” says García Cardiell. “My mother nearly didn’t come to the wedding. It wasn’t a very happy day for her. But Memo never put me in a difficult position. ‘You have to respect that this is hard for them,’ he said.”

It took years, but time again proved García Cardiell’s choice right, as the couple’s happiness became clear and Memo eventually won over the family. He even cared for García Cardiell’s mother in her last days. The couple returned to BYU for graduate school, Pitty in communications and Memo in sociology. He later became a professor of sociology at the Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education and published widely about minority populations.

García Cardiell’s career growth in communications was meteoric. She worked in the male-dominated fields of public relations, marketing, and television production and had to be bold to defy those who dismissed her because of her gender. Her work included establishing a radio and TV station, working for the famous architect Eduardo Terrazas, producing the 1994 World Cup and Super Bowl XXIX for Mexican television, and establishing virtual university and digital literacy programs throughout Latin America for the Monterrey Institute of Technology. She also organized 15 international congresses of education.

Now retired, García Cardiell reflects back on what came of her disobedience. “My experience in following my heart and dealing with my family’s opposition to my desires taught me persistence and prepared me for dealing with difficult situations in public relations,” she says. “And running taught me to work hard, to be disciplined, and to believe. And BYU prepared me in so many ways to live the life I have lived. I know who I am, period. That’s something beautiful in life, that a voice inside is telling you what is wrong, what is right, and that you can do it.”