A BYU research team studies NGOs and why they often fail.

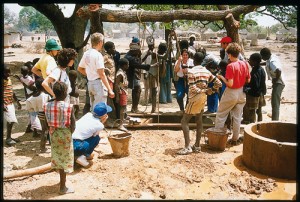

Members of the Ouelessebougou-Utah Alliance (OUA) work with villagers to dig a well in Sirimambougou, Mali, in 1989. Since 1997 a BYU research has been studying the OUA to see what makes NGOs succeed or fail.

Psychology and Sociology

Women in Ouelessebougou, a rural region in the savannah of western Africa’s Mali, spend long days working at the physically demanding tasks of feeding and caring for large families. So when a Utah-based nongovernmental organization (NGO), set up a two-hour evening literacy class for Ouelessebougou villagers, few women attended. They were too tired. And even if they’d had enough energy to attend, most of their husbands would not have allowed them to go out alone at night. Despite the Utah group’s good intentions, its limited understanding of this aspect of Ouelessebougou culture hindered its attempts to improve the women’s literacy.

Eight years ago, however, a team of BYU researchers began to gather insight to help the the Utah NGO, the Ouelessebougou-Utah Alliance (OUA). Inspired in part by a desire to find out what makes NGOs flourish or fail, the team became one of few groups to study the successes and failures of an NGO from an objective standpoint. The team began a 10-year project to study the work of the alliance, founded 20 years ago to help the poverty-stricken and drought-ravaged country with health, education, and economic development.

“In teaching literacy to women, there are cultural barriers that the NGO did not take into consideration but needed to be aware of,” says Bonnie Ballif-Spanvill (BS ’62), a psychology professor and director of BYU‘s Women’s Research Institute who heads the project with Carol Ward, associate professor of sociology, Addie J. Fuhriman (MA ’65), emeritus professor of psychology, and Yodit Solomon (BA ’92), associate researcher at the Women’s Research Institute. “But if they’re aware of these traditions and circumstances, they can find ways to reach these women and help them learn the skills they need.”

Though the team has focused on the OUA for its research, its findings have far-reaching implications for NGOs across the world and have been published in various research journals.

“There are many NGOs that have been started from people’s well-intentioned desires to help other people in the world,” says Ballif-Spanvill. “The problem is that most development projects are not successful because the process of giving and receiving–culture to culture, country to country, people to people–is not well understood. What we have been doing is studying that process and trying to identify what has to happen to create mutually beneficial opportunities for people to grow.”

Cultural Literacy

In studying the OUA and its various projects, the team found that NGOs must first become culturally literate before trying to have an influence on a foreign community. “NGOs often do not carefully consider the traditions and the cultures of the people, and they don’t go in and integrate themselves into that community and that social structure,” says Ballif-Spanvill.

Researcher Yodit Solomon travels to Mali once or twice each year for up to three months at a time; she eats the local food and gets to know the villagers as she speaks with them both in French (the official language) and Bamanankan (Mali’s most widely spoken language). With the help of a local village researcher, she keeps clued in on the culture of the people she talks to, works with, and observes.

After working to understand the culture of the rural Malian villages, Solomon is able to offer the research team detailed insights into why the OUA‘s interventions succeed or fail–insights that are in turn passed on to the OUA to help them better cater their programs to the needs of the people.

Mothers and Daughters

Ballif-Spanvill says that successful cultures are ones that consider and promote the welfare of their women and girls, who in turn lift entire communities. Luce Cannon (BS ’83), a research assistant, notes that a recent dramatic decrease in malnutrition worldwide is directly attributable to literacy increases in women. In Mali, 81 percent of the population is illiterate, and the number of illiterate women is two and a half times that of illiterate men. “The system is absolutely and categorically failing the women,” says Cannon.

“When women are educated, they are more likely to be using better health and sanitation procedures, they have fewer health and reproductive problems, and there is a lower mortality for children. When the women are educated, the whole family benefits,” Ballif-Spanvill says. A frequent problem with NGOs, she adds, is that, however well intended, their projects tend to overlook women, because men are typically able to make their voices heard first. But, she says, “these projects are much more likely to be very effective if they involve women in the planning, coordinating, and timing. So you have to consider the woman’s role and her involvement.”

In Mali the OUA is looking for ways to better meet the needs of women, says Addie Fuhriman. “One of the priorities of the organization is increasing the number of children, and girls in particular, who are in school, because the priority would naturally be for little boys,” she says. “The impact of the research has allowed us to see that little girls need to be in the schools too.”

Giving and Taking

During a break at a literacy meeting in a Mali village, OUA worker Michelle Hagen enjoys a traditional meal with local women. BYU research shows that NGOs are more often successful when workers value the local culture.

Central to the success of an NGO, the team’s research has shown, is the need for the giving, receiving, and learning processes to be collaborative and mutual, rather than one-way. When the alliance set up a clinic-based health-care system, for example, the research team found that the villagers, who were unfamiliar with the style of health care, did not respond enthusiastically or take ownership. The OUA soon shifted to a village health program, which better used the community resources. The change in villager acceptance was quickly visible.

“It was like the light went on,” says Fuhriman. “You could see it in their faces. It was like they were saying, ‘We can do this? This is ours?'”

“In the new approach, they began with the people, so there was identity and ownership, and the people could develop confidence in themselves to solve their own problems,” Ballif-Spanvill says. “Whenever you can engage people in the process, and it becomes a mutual effort, that’s when there will be success.” She acknowledges that there are inevitably times when the people an NGO is helping need assets or training, but, she emphasizes, “there is an enormous amount that they already have, and it’s important for NGOs to appreciate that and capitalize on the strengths that are already there.”

Acknowledging the strengths of the societies it enters, rather than planning patronizingly to “fix” a particular culture, says Ballif-Spanvill, is perhaps the most important key for an NGO. “It’s wonderful to want to help,” she says, “but if you see yourself as the giver and them as the receiver, rather than seeing it as a collaborative effort, you’re in danger of destroying the confidence of the other people.

“Very often people serve out of pity, and that’s the wrong emotion. You need to go in with an appreciation of the person being served as an equal but as someone who has developed in very different ways.”