Robert Frost’s poem “Directive” begins with the following lines:

Back out of all this now too much for us,

Back in a time made simple by the loss

Of detail, burned, dissolved, and broken off

Like graveyard marble sculpture in the weather,

There is a house that is no more a house

Upon a farm that is no more a farm

And in a town that is no more a town.

[Complete Poems of Robert Frost (New York: Holt,

Rinehart and Winston, 1962), p. 520]

I want to take you to a house and a town that are no more. Though the town is still a town, it is no longer the town I’ll take you to. But the house is no more. In fact, the house was never a house, but an inside-out granary, an 8-by-10-foot structure with exposed upright 2 by 4s covered by rough-sawed boards inside. It had an east door and a south window 2 feet square. It was my home from the time I was 3 until I was 9. I remember a single event of our moving in–an image: the furious straining and rush of a pair of horses dragging a cast-iron cookstove on a slip (a sort of earth-going wooden raft) up to the door, the sun flashing off the nickel-plated trim of the stove.

The town is Stringtown, a settlement in 1933 of 11 families strung along a mile of dirt road at the mouth of Georgetown Canyon, a mile east of Georgetown in Bear Lake County, Idaho. When Georgetown was settled in 1872, it was named Twin Creeks (because of an obvious geographical feature). The soil was black loam, deep, rich, without rocks. Brigham Young and George Q. Cannon visited the village a few years after its settlement, and Brigham suggested the village be named in honor of Elder Cannon. So the sign on Highway 30 between Montpelier and Soda Springs reads, “Georgetown, Population 501.” That number includes Stringtown. One of the early settlers was my great grandfather, Alma Hayes, who had been orphaned at Mount Pisgah, Iowa, in 1846 and who, at the age of 6, had walked barefoot among strangers from Mount Pisgah to Provo, Utah, where he nearly starved before his Grandmother Hess learned of his whereabouts and brought him to Farmington to care for him and his younger brother. It was good for me to grow up in Georgetown.

The town is Stringtown, a settlement in 1933 of 11 families strung along a mile of dirt road at the mouth of Georgetown Canyon, a mile east of Georgetown in Bear Lake County, Idaho. When Georgetown was settled in 1872, it was named Twin Creeks (because of an obvious geographical feature). The soil was black loam, deep, rich, without rocks. Brigham Young and George Q. Cannon visited the village a few years after its settlement, and Brigham suggested the village be named in honor of Elder Cannon. So the sign on Highway 30 between Montpelier and Soda Springs reads, “Georgetown, Population 501.” That number includes Stringtown. One of the early settlers was my great grandfather, Alma Hayes, who had been orphaned at Mount Pisgah, Iowa, in 1846 and who, at the age of 6, had walked barefoot among strangers from Mount Pisgah to Provo, Utah, where he nearly starved before his Grandmother Hess learned of his whereabouts and brought him to Farmington to care for him and his younger brother. It was good for me to grow up in Georgetown.

Our granary-house was on the banks of Big Creek, back through the pasture north past my Aunt Vera’s house, through my grandfather’s corral, and beyond his tin-roofed barn. The house was sparsely furnished. The creek was full of native rainbow, cutthroat, and eastern brook trout.

When deep snow covered the ground and the temperature outside was 40 below zero, I have lain deep under mounds of homemade quilts and watched the shimmer of the white-hot cooking surface of the stove, the pipe red-hot to the ceiling while the fire roared in the stove and the wind outside roared against the house.

Pigweed (above) and native trout provided a meal that the young Hayes considered providential.

I knew starvation there. For quite some time in the spring of 1935, we had been subsisting on milk from our single cow and on yellow cornmeal and split peas we had received through the WPAassistance program. Then the cow had gone dry, and we had run out of cornmeal (have you ever eaten leftover cornmeal mush–fried?). We had eaten nothing but split pea soup for several days. I reached a point where I could no longer stomach split peas. My father was away from home looking for work. I told my mother that I was ready to die and would eat no more. She pulled me close to her, told me she was sorry, that we had to keep eating, and asked me to take my little brother down the creek to see if we could find some fish while she would try to find something to go with the fish. That morning the water master had diverted the water from smaller irrigation channels back into Big Creek, and in the small pools left in those channels we found several fish, which we caught with our hands. Mother, in the meantime, had found growing in the abandoned corral a small patch of pigweed (also called lambsquarter), a green much like spinach but milder when cooked. I have always counted that meal providential. Ritually, now 60 years later, I nourish a small patch of pigweed each spring in my garden, enough for a single meal, a reminder of having hungered.

Others during those times also hungered. They came to our home–in ragged coats and trousers, dirty, unshaven, shoes worn through–to beg a bite to eat. Mother always gathered us children into the house. Though she never invited them in, she always fed them: often nothing more than a cup of creek water or a glass of milk and slices of her homemade bread spread with homemade butter and wild currant or chokecherry jelly. They were the hobos who rode the Union Pacific freights, the ones about whom my father sang,

Oh, I went to a house, and I knocked on the door,

The lady said, “Bum, bum, you’ve been here before.”

Hallelujah, I’m a bum. Hallelujah, bum again.

Hallelujah, give us a handout to revive us again.

As a child, I found it strange that they would find our home in Stringtown, for they had to walk a mile from the railroad tracks to Georgetown, pass through Georgetown and walk another mile to Stringtown, and then go through the pasture and the corral past the big barn. How did they know that back behind that big barn and against the creek, a granary they could not see from the road housed a woman who would always feed a beggar? Mother’s comment about them was “You never know who they might be.” When my father was home, he invited them into the house where I listened to them recount their conditions and their travels.

These events taught me of the poor, the meek, the hungry and thirsty, and the pure in heart. They refresh for me my mother’s love and goodness, and a generosity known beyond the tiny community in which we lived. They also remind me that, in this day of abundant wastefulness, while I have much, there are still those who have nothing.

My mother was representative of all mothers in that community. It was a safe community of doors without locks, of people trusting, respecting, looking out for one another, working together, sharing what little they had. I know of no child there of my generation who ever ran away from home. It was a community where youth were nurtured for the roles they would assume as adults. Events in that community were part of the process for helping us come of age and for building, even creating, a society with common values.

Those values were simple, but profound in their influence. Education was essential, and thus reading, mathematics, geography, history, and language arts were essential skills. Every child who hadn’t learned to read at home before starting school learned to read well in the first grade. It was unthinkable that we would not do our homework, and we had homework every night. Other essential values were compassion and kindness, decency, honesty, integrity. So was appreciation of our own and others’ histories and cultures. I often wonder now if our fifth and sixth grade teacher, Mr. Dunford, who scolded us in French when we were unruly and told us countless stories of his experiences in France, did it deliberately to pique our interest in language and culture.

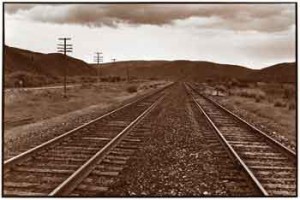

After riding in on Union Pacific freight trains, hungry hobos walked the two miles from these tracks west of Georgetown, Idaho, to the 11-family settlement of Stringtown, where Hayes’ mother always fed them. By watching her example and listening to the hobos’ stories, Hayes became acquainted with the poor, the meek, the hungry and thirsty, and the pure in heart.

We learned also to value the underdog: Virgil Hall, who came as principal for one year and who played softball with us at recess and noon hour, often suspended school until some of us who were not adept at hitting a ball not only hit the ball but scored a run. Sometimes a ball game lasted all afternoon. We knew, moreover, that as citizens of that little school and of that community we were to be responsible. I find it ironic today that parents or public school personnel would ever entertain the notion not to teach values of individual worth, morality, or citizenship.

I remember an incident when I was in fifth grade. Just after the noon hour, the county sheriff, with parents of two boys and the grandfather of another, arrived at school in the sheriff’s car. Within a few minutes, Mr. Nielsen, the principal, called five boys from the classroom and shortly thereafter called all students to gather in the gym. He introduced the sheriff and told us he was visiting the school on official business. The sheriff then explained: During the night, Mr. Hess’s service station had been entered, the place had been messed up, and many items had been stolen. Some of the things taken had been recovered; the thieves, whom he named, had been arrested and would not be attending school the rest of that day or the next, since they must appear before the judge at the county courthouse in Paris. Then the sheriff and his party left, with our classmates in tow. Mr. Nielsen asked us to return to our classes and to our work.

That event affected the community profoundly: the wrongdoers and their act were made known. So was the judge’s decision. The next afternoon the sheriff informed our teachers, who informed us, that the boys were to make full restitution, pay a fine, and remain on probation under parental supervision for a specified time. We were asked not to ridicule the boys since they had been appropriately judged. They were to remain part of us. And together we must get on with our studies and with doing that which was right. Neither those boys nor any of the rest of us ever ran afoul of the law again. I find an irony today in news reports of anonymous wrongdoers. We learned we were responsible to the community for our conduct.

Lewis Munk taught physics, agriculture, and English. He taught us standard English without diminishing the security we felt with our local dialect and without destroying our respect for our elders who used that dialect. His strategy was simple: he taught us a principle of grammar or usage; we practiced that in speaking and writing. I wrote a paper every school day for four years in high school. Often he read only until he found an error we should not have made after his teaching; then he would drop the paper in the wastebasket. Somehow we never disliked him for that.

Farmers still cultivate these fertile fields north of Big Creek. In Hayes’ tiny, rural town, the rhythms of seasons and harvests brought neighbors together for crew work as well as entertainment. Boys and girls learned, as they grew, how to sustain life and perpetuate the values and activities of the community.

Mr. Munk would also send us into the community to collect samples of spoken language that violated the principles he had taught. We attended seriously to the speech of our elders, recording their “errors” on 3-by-5-inch cards–at church, in the store, in public and private activities. Then once a week we would examine our collecting. He would begin class by asking who the most brilliant people in our community were–one week, it would be the most compassionate; another, the most articulate; another, the most inventive. We knew them: we knew that Joe Bee was a m

echanical genius, that Roy Robison was the county’s most persuasive and interesting public speaker, that Aunt Maggie King genuinely cared about each of us, that tiny, gentle Dad Felch was a highly skilled blacksmith. We would discuss all the townspeople in detail. We knew everyone and their strengths and their lack of formal schooling.

Then Mr. Munk would stop. “How did I get off on that? You had an assignment for today. What did you find as you listened to the way people use language?” he would say. On the board we would list the errors we had collected. Then he would ask us to write the corrections beside the errors, and we would discuss what the errors told us about persons who use language that way.

In our innocence and ignorance, at first we would respond with stereotypes–that such speakers were not very intelligent, or not very good, or not very whatever. . . . Then he would have us write the names of our sources for each error. And suddenly, he would seem to notice something. “Wait a minute,” he would say. “Didn’t you just say these people were our village’s best? Is there a contradiction here? Make up your minds.” He led us to know that one’s language does not reflect intelligence or morality or goodness but one’s community and customs and, perhaps, schooling. We learned that English has many varieties and that we might use different varieties for various occasions or purposes, or in different places with different people.

None of us ever disparaged our elders, or others, for their use of language after that. Our elders were our heroes and our models in community conduct. We looked to them for wisdom. I find it ironic today that we study the literature of the Native Americans or similar cultures who look to their grandmothers or grandfathers for wisdom, but we disparage or dishonor our own.

Entertainment was also a community concern. Everyone–young and old–was invited to the dances, the dinners, the Christmas party, the 17th of March Doin’s (as we said in Georgetown), and even, at times, the Old Folks’ Party. Each celebration provided not only fellowship and entertainment but a reaffirmation of community values and the development or display of talents–for all ages. We played out our Halloween pranks following the tradition of our elders–the buggy on the haystack or the barn roof, the upset outdoor plumbing–but always with the admonition not to destroy anything.

Work, too, was a community concern, a fine-tuned apprenticeship for adulthood: men and their sons and grandsons, women and their daughters and granddaughters, men and women working together. A boy learned what a man in the community did; a girl learned what a woman in the community did. My father had a saying he had learned from his mother: “When we have a job to do, we do it, we do it right, and we do it till it’s done.” And we all had jobs at an early age: When I was 6, I rode the horse, keeping him between the rows, while my grandfather or father cultivated the garden and orchard. At 7, I held lambs for the spring docking. You had to hold the lamb on its back on a 2-by-4 rail, its four legs held so that, no matter what, the lamb could not kick the docker in the face. I was part of a crew. Much work was crew work: whether branding or trailing stock, putting up hay, harvesting and threshing grain, preparing the meals, attending to a burial, or replacing a burnt-out barn or house–people worked together.

When one had successfully apprenticed in all the tasks of preparing, planting, nurturing, gathering, and preserving the harvest and then could plan its uses to perpetuate and sustain life, and plant again, one was prepared for full citizenship in the community. When a boy could build a haystack–symmetrical, watertight against the rain and snow–by himself, directing the rest of the crew and controlling the appropriate mix of moist or green and dry hay to guarantee against spontaneous combustion and the loss of the harvest, he was a man. When a girl could oversee the feeding of the haying or threshing crew and provide a meal that outdid the one the day before at some other house, she was a woman. Both were prepared to sustain and perpetuate life and the values and activities of the community. There was dignity in being a significant part of the whole.

Two brief ironies and I am finished. In that nurturing community, not all was perfect, of course. And events may not have affected others as they have me. I may have skimmed only the cream that has risen to the top of the milk that has stood undisturbed a while. But there was enough of goodness to prevail against blatant wrongdoing and foolish failure.

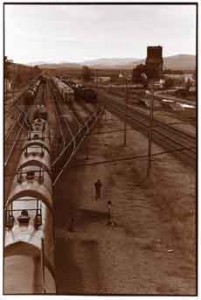

When I was 11, I used to ride the milk truck to spend Saturday in Montpelier with a close friend. My Uncle Albert, a Union Pacific Railroad engineer who ran the switch engine in the Montpelier yards, had brought Delmer and me together. Delmer’s father was a porter for Union Pacific. Though we occasionally spent some time at his home, most of the morning found us in that great steam locomotive with my uncle, riding back and forth, bumping railroad cars into a train destined for points east or west. We felt important, riding in the cab of that great engine, watching the gauges, feeling the heat from the fire that helped fuel that great iron horse. At the noon whistle on the Roundhouse, we went routinely to the Grand Cafe, where for 50 cents we could have either a salisbury or chicken-fried steak dinner. We laughed and talked and planned the next Saturday over dinner; then at 2 o’clock we parted and I caught the milk truck home.

O

ne morning during Christmas vacation (it was December 1941), the milk-truck driver let me off at Delmer’s as usual. As I crossed the bridge over the stream to his house, I noticed the front windows of the house were smashed and the door was open. The house was vacant. Painted on the walls in the room where two weeks before I had stood with Delmer near the heaterola and soaked up the warmth of his family, I read, “Dam nigger.” I was stunned. When I turned to the door at the sound of footsteps, a frightening old man asked me, “You lookin’ for that nigger kid?”

“No, I’m looking for Delmer.”

“Yeah. That nigger kid.”

I fled past him across the bridge, to the street, and toward the railroad yard, where I would find my uncle, my mind in turmoil, uncomprehending. As I passed Gamble’s Hardware, I saw the full-length crack in the plate-glass display window and the words “Nazi Go Home” painted in red. A black swastika marked the door.

The Grand Cafe farther down the street was closed. A hand-painted sign inside the window read,

CLOSED.

VERY SORRY.

On the outside of the window, someone had painted, “Dirty Jap.”

Hayes and his friend Delmer spent hours at the Montpelier, Idaho, train station (above) and switching yards, where Hayes’ Uncle Albert ran the switch engine. The boy’s friendship ended abruptly when racial prejudice, intensified by World War II, forced Delmer’s family to move.

In the Roundhouse, I found my uncle. He didn’t ask where Delmer was. We didn’t talk much that morning as he bumped cars together. When the noon whistle blew, he told me he had a sandwich for me in his lunch bucket. I wasn’t hungry. I felt I was a stranger in a strange and dangerous land. At 1:30 he stopped at the station to let me off and told me that in a half hour the milk truck would be across the street from the cafe.

It was there earlier than usual, and the driver was standing at the curb, waiting. He opened the door for me and shut it after I was seated. Then he went around and got in.

When he asked how I was, I began to cry. He put his hand on my shoulder and said, “Yes, at the creamery I heard what happened. It’s sad what hatred does to people. It’s sad what war does to people.”When I got home, I recounted the events of the day to my mother, and I cried again. “I’m sorry,” she said. “I thought once that I should warn you, but I knew it didn’t matter.”When I was 16, a man I worked for, a man I love as I love my father, told me, in one of those conversations in which people come so close together that there is no reason for secrets of any sort on either side, that a delegation of concerned parents had asked him to ask me to stop associating with the Mexican kids in town. There were two families. He made it clear to me that he did not agree with those who had approached him, but they had prevailed upon him. I think I was the only friend Viktor Madrid had. I thought of the times I had walked the two miles to his sheep camp just to be with him and to eat Mrs. Madrid’s tortillas and mutton stew and to listen to Mr. Madrid speak to me in Spanish. He spoke English to other gringos but never anything but Spanish to me. I thought of the times Viktor had come home with me. Without anger, feeling again the loss of Delmer, I said something I had never said to my elders before. I said quietly, without heat, “Tell them to go to hell.”My few years and limited experience have led me to believe we must create the kinds of communities we desire; we cannot assume they will perpetuate themselves indefinitely without tending. Left alone, they diminish and decay like a garden or a house abandoned. I am reminded that it is they who hunger and thirst after righteousness that are blessed. I am reminded of the importance of feeding the hungry and taking in the stranger.

–Darwin L. Hayes is a BYU Professor Emeritus of English. This article was given as the English department awards banquet address in 1995. -PHOTO CREDITS- Photographs of Stringtown and Montpelier, Idaho, were taken by John Snyder in June of 1999. Early 1970’s view of the now-dismantled granary (p.1 of this article), courtesy of Darwin L. Hayes.