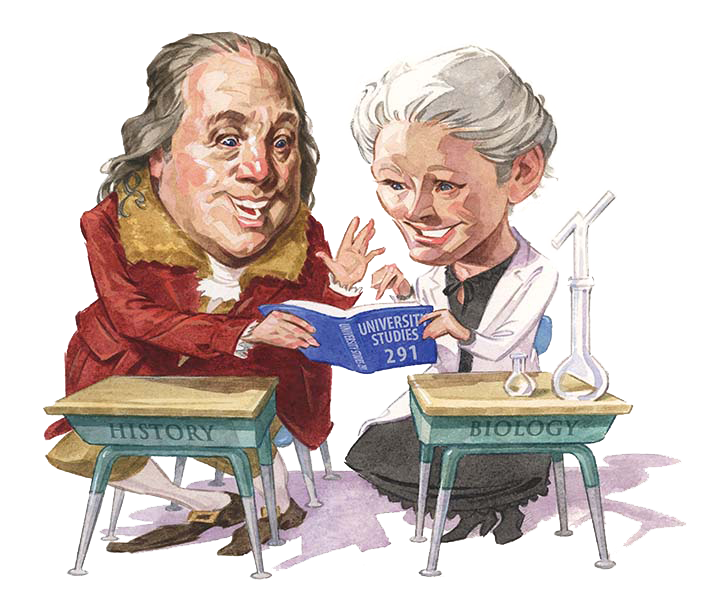

A revolutionary course explores the intellectual intersections of two disciplines.

An unrehearsed rendition of “Come Thou Fount of Every Blessing” echoes down the Maeser Building’s marble hallways. From the front of the classroom, Richard A. Gill (BS ’93), associate professor of biology, tells his 30 students that he loves the hymn because it depicts “the great effort and discipline that are required to reconcile us to God.” And the goal of this class—Unexpected Connections—is to “do a very small version of that, asking you to reconcile two ways of viewing the world,” he says.

Welcome to one of BYU’s three newest general education and honors courses, which invite students to explore the connections between two disciplines: physical science and culture, social science and art, or biology and

letters. In this section Gill and Matthew E. Mason, associate professor of history, are addressing the causes and consequences of revolution.

“So let’s look at this historical view of revolution like a biologist,” Gill suggests. Any revolution—political, cultural, or technological—is preceded by “a motivating factor, some sort of inefficiency in the system,” he says.

“When in life are you most likely to perceive inefficiencies? It’s 18 to 25, as your frontal lobe is being developed. When you are young, you are cued up in terms of your neurobiology to see this and to push for revolution; that is when you are most likely to be willing to self-sacrifice for the good of an idea.”

After weeks of insights from history, students are ready to explore today’s digital revolution. For two weeks they adopt the role of digital revolutionaries, shunning paper and pen and voice calls for blog discussions, e-mail, texting, and Skype. The next two weeks, they become counter-revolutionaries, leaving their phones at home whenever practical, writing in analog journals, making personal visits instead of calling, reading books, and doing research in the library stacks. The final two weeks, they are reformers, working to find a balanced approach.

Mason says that this experiential element ended up being “the thing we did that had the biggest impact on the students, getting many of them to be more thoughtful about how they interact with the revolution in their lives.”

And commenting on blogs or engaging in lively class conversations, they were able to be more thoughtful interacting with others’ views. Gill says it’s exciting when students realize that those with differing opinions are not “dumb,” but rather “their brains are actually responding and adapting to their experiences.”

Student Amanda Berg (’17) agrees. “I think the thing that changed most for me is my willingness to understand other people’s opinions better,” she says. “This has helped me to understand that it is past experiences which cause people to think a certain way.”

How to understand and appreciate different perspectives was a lesson even Gill and Mason learned in teaching the experimental class. “Dr. Mason presented this really compelling argument of ‘this is what a revolution looks like,’” says Gill. “When we switched places a bit, I wanted to try to fit my view of science into that model. And the real insight came that it was different.”

Gill found that in historical research, revolutions are displacing—an old model is replaced with something novel—whereas almost all scientific revolutions involve a synthesis, as in the case of evolution and genetics merging to form much of modern biology.

“When we were identifying gaps in our knowledge and filling them in, I think that’s when the students really perked up,” he says.

On the last day of class, Mason asks students if their views of revolutions have changed. “Before, I thought that revolutions were something in the past,” says Bret S. Blackham (’17). “Now I can analyze revolutions going on around me and see the consequences. What do I feel should happen? Can I do something about it?”