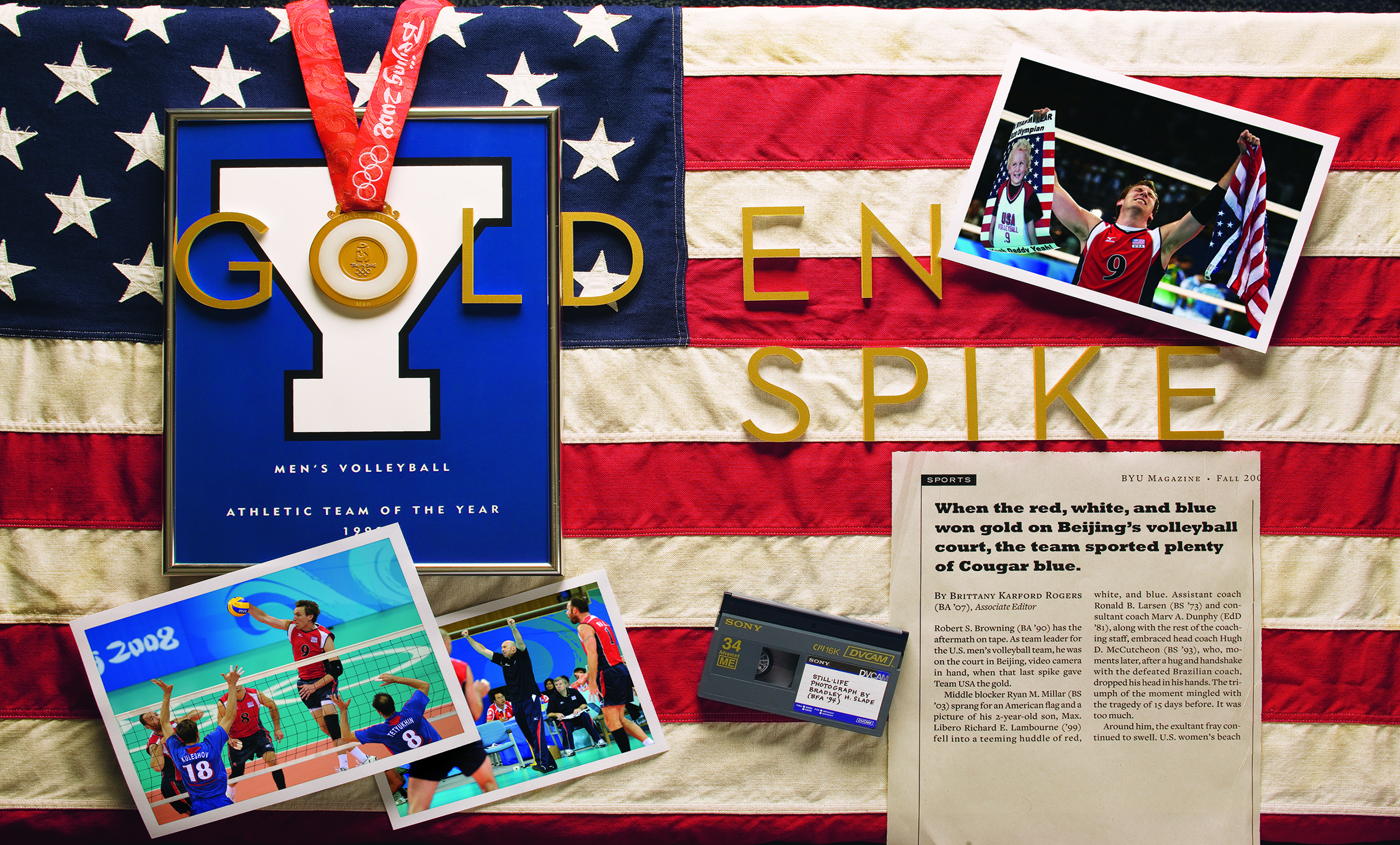

Golden Spike

Golden Spike

When the red, white, and blue won gold on Beijing’s volleyball court, the team sported plenty of Cougar blue.

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07) in the Fall 2008 Issue

Still-life photograph by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

Robert S. Browning (BA ’90) has the aftermath on tape. As team leader for the U.S. men’s volleyball team, he was on the court in Beijing, video camera in hand, when that last spike gave Team USA the gold.

Middle blocker Ryan M. Millar (BS ’03) sprang for an American flag and a picture of his 2-year-old son, Max. Libero Richard E. Lambourne (’99) fell into a teeming huddle of red, white, and blue. Assistant coach Ronald B. Larsen (BS ’73) and consultant coach Marv A. Dunphy (EdD ’81), along with the rest of the coaching staff, embraced head coach Hugh D. McCutcheon (BS ’93), who, moments later, after a hug and handshake with the defeated Brazilian coach, dropped his head in his hands. The triumph of the moment mingled with the tragedy of 15 days before. It was too much.

Around him, the exultant fray continued to swell. U.S. women’s beach volleyball coach Troy R. Tanner (MA ’02) made his way down to congratulate the men’s team. And from the stands, team scout Carl M. McGown (BS ’63) cheered on.

“It was amazing to see all of these people there,” says Browning, whose job at the Olympic Games was to handle the logistics—transportation, media, that sort of thing—for the team. “I was looking around and seeing Carl and Rich and Ryan and Hugh and Troy and Ron and Marv. It was amazing in particular to see all of us who were involved in that first [BYU] national championship team in ’99. And here we are all together again at the Olympics, suddenly winning the gold medal, . . . and Hugh’s the man in charge of the whole show.”

At BYU, these are the names of volleyball lore.

Cougars on the Court

The BYU men’s volleyball team claimed its first national championship in 1999 with a squad that featured Millar and Lambourne on the court, Olympic veteran McGown as coach, and future USA Volleyball mainstays McCutcheon, Tanner, and Browning as assistant coaches. Dunphy and Larsen also had earlier careers at BYU.

But how did all these Cougars end up with USA Volleyball?

“That’s a good question,” says Millar.

“When you’re coaching in any major event,” explains McCutcheon, “you want to work with people you know are good, . . . people who are at least philosophically aligned with the way you do things.”

For Browning, the answer is clear, and it’s rooted in the quality of their training: “There is one reason why so many Cougars landed on the Olympic team, and it’s Carl McGown.” Indeed, at one point or another, each of the seven was under the tutelage of McGown, who was prominent in national volleyball circles and coached BYU’s team for 13 years.

“I’m not sure what the adjectives are,” says McGown, seeking to describe watching his former players and apprentices reach the pinnacle of their sport in Beijing, where McGown himself scouted other teams on behalf of Team USA. “You’re deeply satisfied. There are just all kinds of wonderful emotions.” It was McGown’s seventh Olympic Games on the U.S. coaching staff, and it had been 20 years since he last saw the U.S. players with gold around their necks. (Tanner played on that 1988 gold medal team, which Dunphy coached.) The last medal for the team had been bronze in 1992.

The Trail to Beijing

McCutcheon, who played and coached for McGown at BYU, got involved with USA Volleyball in 2002. He signed on as the head men’s coach in 2004, grateful for the presence on the team of Millar and Lambourne—both of whom he had coached as an assistant at the Y. “You have to earn [respect] a little bit more with the national athletes to get the buy-in you need to make changes,” McCutcheon says. “Having a couple guys there who already knew me and the way I wanted to teach the game and coach the team helped the transition.”

“If Hugh was phenomenal in one aspect, it was this: everyone played for the team and not for themselves,” says Larsen, McCutcheon’s assistant. “We were invested in each other and in this team goal to win a medal.”

Five players on the squad were Olympic veterans returning for a second, third, or fourth attempt at gold. Millar was one of them. Returning for the third time, he had experienced placing second-to-last in Sydney and then narrowly missing the medal stand in Athens. For the former three-time collegiate All-American, the team had something to prove, and McCutcheon was going to lead them to it.

Yet the unexpected—the unspeakable—occurred the day before the Games would start. McCutcheon’s wife, Elisabeth, and her parents, Todd and Barbara Bachman, were attacked by a man with a knife while touring the Drum Tower, a popular Beijing tourist site. Elisabeth went unharmed; her father, however, was killed, and her mother sustained serious injuries.

McCutcheon tended to his family immediately, his absence from the team indefinite.

“You have all this hope and optimism going in,” says Millar, “and then something like this puts a dark cloud over everything. We only had a few days to get over it—I can’t imagine what it was like for Hugh.”

Larsen stepped in as interim head coach, and the team won its first three matches without McCutcheon.

“The fact that [Hugh] was unable to be on the sidelines with us the first few matches was not irrelevant,” says Lambourne. “But certainly, he had put in a great deal of work, and that ended up carrying us, even in his absence.”

Going for Gold

McCutcheon’s return for game four fueled the team’s momentum. “Both my wife and my mother-in-law and the rest of my family were very much encouraging me to stay and to try to finish what we started,” says McCutcheon. “They’re big supporters of USA Volleyball. They knew how much had gone into it.”

The quarter- and semifinals would be the true tests. Both matches came down to the fifth set—a game to 15 points instead of 25. Facing Serbia in the quarterfinals, the Americans, down 4-7 in the fifth, had to claw their way back. “It was a five-game thriller, and the boys pulled it out,” says McGown.

Team USA advanced to the semis to meet Russia—perceived by McGown, after scouting out all the competition, as the biggest threat. “That fifth set [against Russia] came down to who was going to make the plays at the end,” says Millar. “And we gutted out a victory.” Team USA was headed to the gold-medal match.

They couldn’t have been more confident going in. They’d already beaten their opponent—no. 1–ranked Brazil—within the last month at the World League Championship, played in Rio de Janeiro, claiming their first World League title. And while volleyball was not aired during primetime hours back in the states during the Olympics, the Americans had an entire country rallying around them. “Because of the circumstances surrounding the death of Todd Bachman, we became the nation’s team in many ways,” says Larsen.

The final was a four-set match. In the last set, Lambourne made a key dig that the team converted for a point, tying the game at 20. Millar took the team to match point with a kill from the middle. A few plays later, the team had the gold.

The tragic events that had forced the U.S. men’s volleyball team into the spotlight turned all eyes on McCutcheon in those first celebratory moments after the match.

“I stepped out and had a moment to myself,” says McCutcheon. “I was overwhelmed.”

Elsewhere, Lambourne, Millar, and other U.S. players ran around the court, pointing and waving to loved ones in the stands. Coaches grinned and congratulated. There were interviews. McCutcheon returned to the celebration; the euphoria, tempered by tragedy, would be enjoyed to its fullest.

“I told Rich and Carl, after we won this Olympic gold together, ‘It’s like winning the national championship in ’99,’” says Millar. “Except this time, it’s just a little bit better.”