By Tad Walch

When George D. Nelson arrived at BYU in 1972 as a freshman walk-on for the football team, he hoped to be LaVell Edwards’ first quarterback and planned to become a lawyer.

According to Nelson, only divine intervention could have turned him into a BYU associate professor of theatre and film who recently earned national recognition for his work using theatre to rehabilitate young criminal offenders.

Fortunately, divine intervention is exactly what happened. Now the American Alliance for Theatre and Education (AATE) has named Nelson the 1995 recipient of the Lin Wright Special Recognition Award, the past recipients of which include the Seattle Repertory Theatre, CBS, and the National Endowment for the Arts. The prestige of the award is a fitting honor for the success of Nelson’s innovative program. Under the name Clime International, Nelson’s work is touching the lives of more than 100,000 criminals in 10 states and four countries.

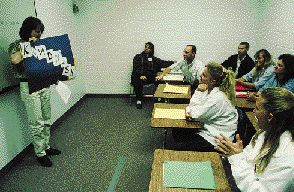

George Nelson helps reform young criminals by teaching them in a way they like to be taught – through theatre.

How successful is Nelson’s program? “We had one offender who was due to be released from a residential lockup facility before he could finish George’s course,” says Melissa Venner, a Corrections Department administrator in Harris County, Texas. “He actually asked to stay locked up until he could finish the program.”

Nelson says the reason young offenders enjoy the program so much is it uses theatrical and psychological principles; it teaches them in a way they like to be taught.

“One of the first things we do is an exercise to help people understand their personality style,” he says. “One personality type, the Sensory Perceiving group, makes up the majority of the offender population. These are the at-risk students we always hear about. The reason these students are ‘at risk’ is that they learn in a completely different way than our public school system offers.”

Nelson is not the first to believe that the way to reach this group is through theatre; however, he is the first to find a way to reach more than a handful of them at one time. He has produced 84 lessons that correctional facilities use after their instructors are trained by Nelson to properly use the techniques to which the offender population responds.

The 41-year-old former LDS bishop has a unique perspective of the criminal population: He belongs to the same personality group as most of them. “That’s one of the reasons this is so important to me,” Nelson says.

Another important project to Nelson is providing theatre teachers across the country with more than 1,000 step-by-step lesson plans through an Internet web site. (The site is found at https://www.byu.ed:80/tmcbucs/arts-ed/StanHome.html.)

In addition to those national programs, which have made him a popular workshop presenter, Nelson carries a heavy teaching load as the theatre education program coordinator in the Department of Theatre and Film. He also directs training films, infomercials, plays, and music videos.

“The range of his projects has really been phenomenal,” says Harold Oaks, the BYU professor whose class changed Nelson’s life when Nelson stumbled upon it in 1972. “Where the rest of us may need to focus on fewer things to do them really well, George’s abundant energy allows him to be involved in more things and to be successful in all of them. He usually does so with exceptional skill and inventiveness.”

Such exceptional skill was evident when Nelson was a star high school quarterback in New Jersey who spurned several small-college scholarship offers to attend BYU.

He practiced with the Cougars as a freshman but realized that at his size, and because of theatre (which he found through football), his future was elsewhere.

“I was a political science major who needed a morning class so I could go to football practice in the afternoon,” he says of his freshman year. “The Theatre Department had a graduate class in educational theatre, but they took me because they needed people in the class.”

Oaks was the teacher of that class. Through the course, Oaks taught Nelson and his classmates that theatre is an outstanding teaching tool and can be used to enhance education and build empathy.

“As I was involved in that class, I was trying to figure out what I was going to do with my life,” Nelson says. “My patriarchal blessing was real clear that I needed to seek the Lord’s guidance in my profession. I had never done that. I made it a matter of very heavy prayer. That class became the answer to my prayer–using theatre to teach needed to be what I did. I changed my major and went into theatre, much to the dismay of my parents and everybody else.”

The dismay has not lingered. Nelson’s inherent energy helped him through BYU in three years, and he completed his four-year master of fine arts program at the University of Washington in just two. It was at the University of Texas, where he was teaching secondary education teachers how to teach theatre, that he was approached about working with criminals.

The work quickly expanded into a successful business, the forerunner of Clime International.

Nelson left academia in 1983 when his new business grew too large, but he was ready to return when BYU offered him a position in 1990. Oaks, then chair of the department, was pleased: “George has taken over a

program (theatre education) which has always had a solid base, but the enrollment and enthusiasm had dropped off. George has reinvigorated the program. According to people who are hiring our students, the training of those students has improved and the program is very well respected.”

Oaks says one of Nelson’s students told his review committee–Nelson is a candidate for continuing status–that she had been looking for “a mentor among the faculty that represented the kind of influence Robin Williams’ character had on his students in Dead Poets Society–someone able to fire young minds with his energy. She said George was that teacher.”

Corrections Administrator Venner, who helps run Harris County’s boot camps for young first-time offenders, says Nelson’s enthusiastic example and program have changed her view of the Texas requirement to teach life skills at the camps. “I didn’t believe in life skills, but this program has made a believer out of me,” she says. “George’s enthusiasm for it extends through us and is carried right to the students.”

Nelson is developing a study of the program’s effectiveness, but Venner says Harris County’s boot camp is proof that it works. The camp has a far better recidivism rate than others around the country: Only about 15 percent of young offenders who go through the camp return to the criminal justice system.

“What I’m trying to do,” says Nelson, “is say, ‘How does the offender population, or this at-risk population, learn?’ We’re not teaching anything different than anyone else; we’re just teaching it differently.”

Keeping first-time offenders from repeating, says Nelson, involves helping them learn empathy and realize that they have values, too: “An offender believes what he needs supersedes what you need. But if I can help him to understand that everybody has needs and to gain empathy for others, the likelihood of his committing a crime again is very low.”

First, an activity helps the offenders understand where they are and where they want to be. “Then we find out who they really are by finding out what personality type they are.”

This can be an amazing lesson for the offenders, Nelson adds. “One gang member in a Los Angeles jail said to a rival gang member in his same personality group, ‘You know, I may run across you in the street, and I may be required by my gang to kill you. But now I realize that I have more in common with you than my own gang. And I’m Hispanic and you’re Black.’ “

The next step is designed to motivate participants to develop empathy through a simple application of theatre. By creating a commercial about an opposite personality style, the inmates “learn how hard it is to understand the world from somebody else’s perspective,” says Nelson.

Perhaps most intriguing is Nelson’s belief that criminals have values but have allowed their actions to deviate from what they believe. “We’re

filling our prisons with people who shouldn’t be in prison. Very few of them don’t have values.”

Nelson, who served a mission in California and is raising six children with

his wife Leslie, bases his program on principles he’s learned in the Church.

“I can’t say, ‘Wickedness never was happiness. You need to repent,’ ” he notes. “But I can say, ‘You can’t be happy in your life because you’re not living consistent with what you know is right.’ I can use role-playing to illustrate it. The golden question in acting is ‘What is it the character really wants?’ I use the golden question here: ‘What is it you really want?’

” ‘I want to be home with my wife and children.’

” ‘Well, you’re behind bars. How can I help you be home with your wife and children?’

“It’s not, ‘I’m going to force you to change your life.’ It’s, ‘I’m going to help you get what you want.’

“If they begin to understand these things, they realize that they need to make themselves whole. When they start to act in their own self-interest based on what they really want, a different person comes out the other end.”

A program that makes such a difference in people’s lives is what the AATE wanted to recognize, according to Karina Naumer, the organization’s awards coordinator: “Our adjudicators felt his work was innovative and very much needed in our society.”

In retrospect, it would be hard to imagine Nelson making such a large scale contribution to society on the football field.

For more information about George Nelson’s work with criminal offenders, call (801) 378-4269.