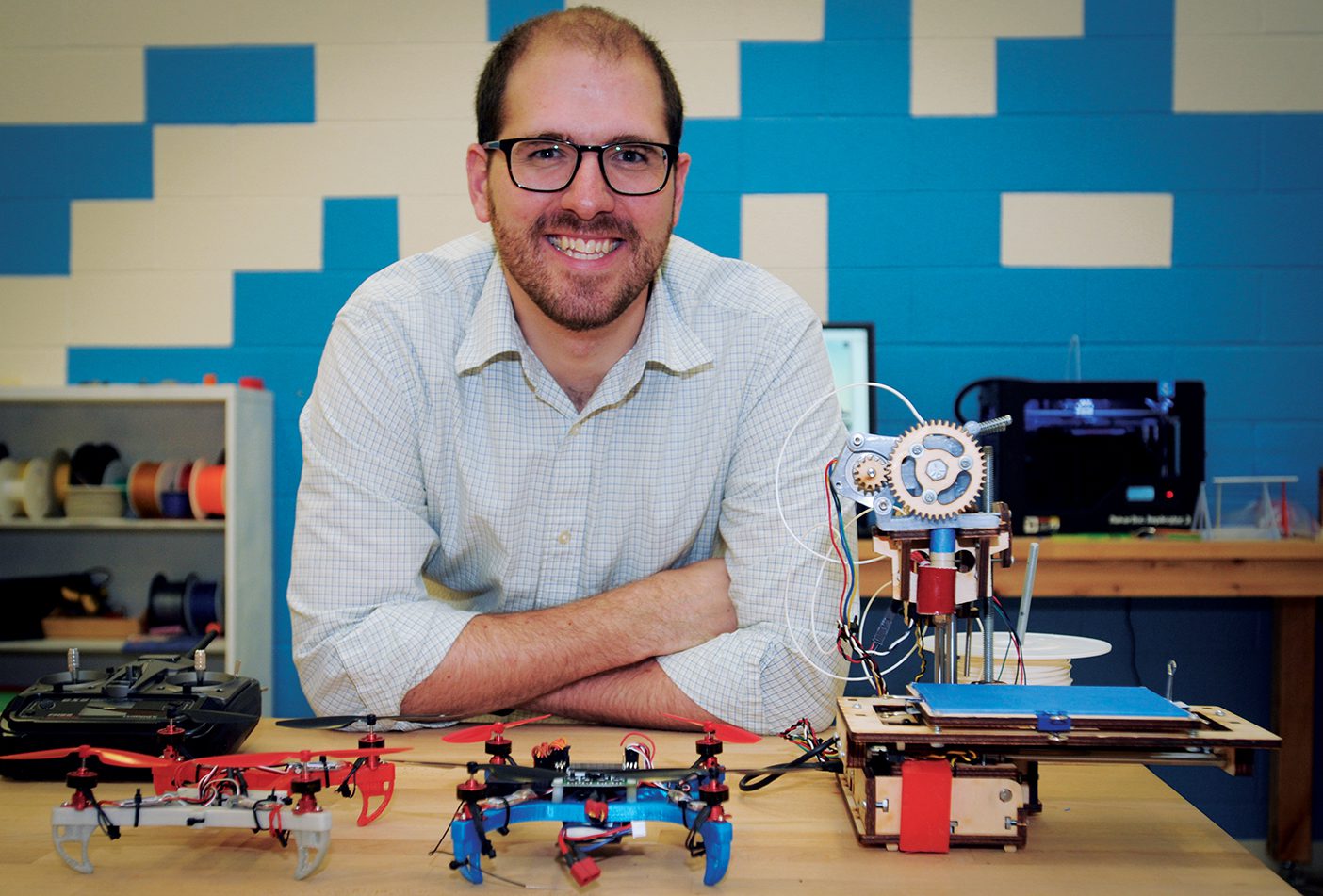

A BYU history grad is helping rewrite the narrative for disadvantaged youth in Baltimore.

“You and I are here upon the earth to prepare for eternity, to learn how to learn, to learn things that are temporally important and eternally essential, and to assist others in learning wisdom and truth.” Those words, spoken by Elder David A. Bednar (BA ’76, MA ’77) at the April 2008 BYU commencement, stuck with history student Andrew B. Coy (BA ’09).

After graduating the next year, Coy signed up for Teach for America and was soon standing in a classroom at Digital Harbor High School in Baltimore, Maryland. Seeking to create opportunities for his low-income and minority students, Coy started an after-school tech club to teach teens how to build websites. When a local rec center shut down, the club moved in and was renamed the Digital Harbor Foundation.

In their tech center, Baltimore youth program robots, code software, and create 3-D-printed masterpieces. It’s a place where they can imagine, collaborate, try, fail, and try again. Coy’s work on interactive and collective learning eventually led to his appointment as a senior advisor in the Obama White House, where he helped lead the Nation of Makers initiative. Here he shares insights on how to prepare disadvantaged youth for the changing workforce and expand their perspective about their place in the world.

How did teaching in Baltimore change your perception of education?

Coy: It was overwhelming. Being a teacher is incredibly hard work, especially in a high-needs area. After school, problems would happen that the kids would bring to school the next day. It felt like there was more need than we could meet during school.

“It felt like there was more need than we could meet during school.” —Andrew Coy

How does being “high need” affect a child’s life and career trajectories?

Coy: There are so many things that life has thrown at these kids. To get out of situations like poverty, they have to do everything perfectly for 20 years. Any mistake is potentially fatal—sometimes literally, but also figuratively, in the sense of pulling them off of the path that gets them out. That’s really one of the defining differences between privilege and lack thereof—the ability to recover from mistakes.

In my classes I would teach about people who made the technology we use today, talking about dorm rooms and garages. Then I was like, “Wait a second—my kids don’t have garages. They’re in row homes in Baltimore.” Too many of them aren’t making it to the college dorm room. The kids have ideas that could be a next big thing, but they don’t have the network of support they need. Many have a love for technology or creativity, but they don’t have a clear pathway from the classroom to a career. It’s the informal opportunities that make a difference.

What inspired you to create the Digital Harbor Foundation?

Coy: One day I told my students that I could get them a job making a website—a fantastic interdisciplinary experience that mixes technical components, the words on the page, visual communication, and graphic design. So I taught them web development, and they made a website for the client and got paid. More kids came knocking on my door: “Do you have any more jobs?” I kept finding opportunities to apply real-world learning. That was how it started, as an after-school club. As it grew, I would invite folks from the community to come meet the kids. When the city shut down a nearby rec center, I said, “What if we turned this rec center into a tech center?”

What can a tech center do better than a traditional classroom?

Coy: School can be like eating a cup of flour, having a drink of water, and eating yeast and salt. The ingredients are good, but it’s a disgusting way to eat bread. Bread is only bread when you mix the ingredients, give it time to rise, and cook it. This is why students always say, “When am I going to use this? Why does this matter?” When in the experience of traditional education are we mixing the ingredients of knowledge?

Too often the dominant focus in education is on compliance. There are reasons why it’s that way. But, what it’s unintentionally communicating to the young person is that the world is something that happens to you, instead of something that you can design. But if you can realize that much of the world was designed by people and that you are a person who can make a piece of your world, it changes your perspective. That level of realization is so rare in the current educational environment.

“If you can realize that much of the world was designed by people and that you are a person who can make a piece of your world, it changes your perspective.” —Andrew Coy

How does becoming a “maker” change a child?

Coy: The maker movement is about imagination coupled with creation. It connects to some of the deepest pieces of what it means to be human, what it means to be creative. It’s the start to divinity. How can we allow more people to experience that and to feel empowered in their day-to-day experiences instead of that the world is happening to them?

I remember asking a young man named Darius McCoy, “Do you want to build a 3-D printer?” He’d only come that day because he was tagging along with one of his friends. He was like, “I guess. I don’t know what 3-D printers are, but I’ll give it a shot.” Then every single day he came after school to work on it, eight weeks in a row. He had to take it apart and put it back together, but eventually it worked. I could see this transformation in how he saw himself. Not only did he make something but he made something that made other things. Today he works at Digital Harbor as an employee, managing the youth employee program and the 3-D print shop. He’s still in his early 20s, but he’s recognized nationally for his expertise in 3-D printing.

How can we better prepare students for the future?

Coy: The tragedy of the American Dust Bowl was that the knowledge for how to farm in a way that could have prevented it already existed at the time. That knowledge just wasn’t distributed to the frontline homestead farmers. I think we’re in a digital dust bowl at the moment. When it comes to technology education, we are deficient, and especially in educating women and minorities. More and more every job is a tech job or tech enabled.

When it comes to technology, it doesn’t matter what you learn right now. It’s going to be obsolete. So you have to learn how to learn, and you have to learn to love learning to keep doing it.

With the Digital Harbor Foundation and the maker movement, we’re building a robust network for students to have access. Because they have the creativity, they have the potential, they have the desire. They just need the place and the support to get there.