Hands on Hearts

A BYU program is sending doctors, sonographers, and students across the Pacific to help relieve a hidden sorrow.

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04) in the Fall 2018 Issue

Photography by Nathaniel R. Edwards

A splash of blue and yellow pixels swirls among pulsing bursts of red on the dark screen. From the examination table—really just a few worn wooden classroom desks pushed together and draped with a floral cloth—a schoolboy cranes his neck to see the flashing patterns on the screen. His brown eyes flit from the screen to the face of the foreigner at his side, the woman with a hand on his heart.

The boy will soon learn that, in an echocardiogram of the heart’s mitral valve, blue is bad and represents a turbid spurt of backflow in what should be a one-way route of blood from the left atrium to the left ventricle. Too much backflowing blue—or “regurgitation” of blood—and the heart becomes inefficient and enlarged and can even fail. Such are the ravages of rheumatic heart disease.

For the Rheumatic Relief team—the doctors, sonographers, and dozens of BYU students who have come across the Pacific to peer into the hearts of schoolchildren—it’s hard to see the islands of Samoa as anything but a tropical paradise. Foamy blue surf crashes onto volcanic coastline, ubiquitous foliage is interrupted by sparkling waterfalls and abundant flowers, and bright smiles and waving hands greet at every turn.

But the beauty belies a hidden sorrow, one that team member Colton T. Murray (’20) came to know while serving a mission in Samoa. “Anytime anyone died,” he recalls, “you’d ask what it was, and—almost always—it was ma’i o le fatu, ‘sickness of the heart.’”

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), highly preventable and largely forgotten in developed countries today, stubbornly clings on in developing nations. The islands of the South Pacific, and especially Samoa and American Samoa, are particularly hard hit.

Working with the Samoan Ministry of Health, BYU’s three-pronged Rheumatic Relief program seeks to turn that trend around—with a public-health intervention to teach children and parents preventive steps, a health screening to find undiagnosed cases, and genetic research to get to the bottom of the problem.

Heartache and Hope

A beautiful young woman staggering down a hallway. John S. K. Kauwe (BS ’99, MS ’03) will never forget the image of that first child he saw afflicted with RHD. She “could barely walk . . . without being doubled over in exhaustion,” he recalls six years after his first trip with the team. For Kauwe, a BYU biology professor who serves as an associate director of Rheumatic Relief, the memory remains fresh, both in its pain and in its joy.

“We were able to communicate with local health officials and her parents to get her the help that she needed,” he says. “The feelings I have, both of sorrow for her suffering and gratitude for the chance we had to help her, inspire me even today to be committed to this work.”

That work got its start several years earlier, in 2009, an outgrowth of PhD research by Lori Bowen Allen (BS ’84, MS ’01), a former BYU track athlete and student of health promotion. The director of Rheumatic Relief, she serves today as a BYU adjunct faculty member. Her focus is on prevention, and her mantra is simple—treat strep throat, stop RHD. Prevention, she elaborates, hinges on the child receiving a timely course of antibiotics at the first signs of a streptococcus infection, before it becomes rheumatic fever, which can damage tissues in the heart and other parts of the body.

She enlisted the help of her husband, Marvin R. Allen (BS ’85), a cardiologist and a former linebacker on BYU’s 1984 National Championship team. The main goal for Marv, the Rheumatic Relief clinical director, is to catch the kids with signs of RHD who would otherwise go undetected and refer them to the Ministry of Health for appropriate interventions—interventions that make a normal life a real possibility for most.

“I was captivated by the vision of [the Allens],” says Kauwe. “Their commitment to serve the people of Samoa and teaching and mentoring [BYU] students in the process was and is inspiring.”

The Allens have led groups, which include specialists from Provo and from as far away as the Mayo Clinic, to Samoa since 2009, educating and screening tens of thousands of children. In 2018 alone, Rheumatic Relief visited 24 schools and examined 6,288 students, identifying heart abnormalities in 150 of them, who were then referred to the Ministry of Health for treatment.

“It’s not an overstatement to say that lives are being saved,” Lori says of her most recent trip, the third since BYU became an official partner in 2016. “Children’s lives.”

The Song and Dance

Want to have an impact in the Samoan classroom? Then you’ve got to break out the moves, and you definitely have to sing, says Taylor J. Avei (’19), a half-Samoan premed student at BYU and a second-year Rheumatic Relief intern. “Samoan children are taught from the time they are born to sing, dance, and listen to the beats and rhythms around them.”

And so, sitting cross-legged on woven mats in open-air classrooms with brightly painted cinderblock walls, a huddle of Samoan children watch, wide-eyed at first, as these white visitors strum the ukulele, clap, bounce around, and belt out in Samoan:

Tale, mafatua, fa’apea le fiva,

(The cough, sneeze, and fever,)

manava, ulu, taliga, fa’ai tiga—

(stomachache, headache, earaches, and sore throat—)

o fa’ailoga ia o le rumatika.

(these are the symptoms of rheumatic fever.)

Va’ai le foma’i. Tui penisini e aoga.

(See the doctor. Get your penicillin shot to cure it.)

Ruma Ruma Ruma Rumatikalalala

If the lyrics for “Rumatikalalala” fall on the didactic side, the schoolchildren don’t seem to mind. Within minutes, they’ve memorized the song, which borrows its tune from an old Samoan favorite, and have joined in dancing and clapping along with their new friends.

The BYU interns then stretch out a sheet decorated with an island scene and, with dolls on their hands and voices pitched to silly, present something most of the children have never seen—a puppet show. They act out a simple story—again, entirely in Samoan—about how to keep a sore throat from becoming a sick heart. With audiences ranging from 3 to 16, the interns adapt as needed, sprinkling in enough humor to keep it lively.

Lori Allen has honed the interns’ repertoire over a decade of trips. And her follow-up research, which she has shared at international public-health conferences, shows that concepts delivered via song, dance, and puppet shows get through to and stick with these children, even many years later.

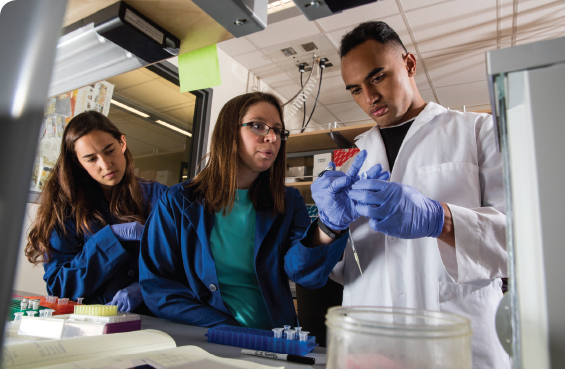

The BYU student interns, 28 in 2018, come from a variety of academic backgrounds, and most don’t speak Samoan. During the semester before their trip, Avei, along with other Samoa returned missionaries, helped them learn the songs and puppet show. Native Samoans Justina P. Tavana (’23), a PhD student who serves as the administrative coordinator for the program, and her father, Gaugau V. Tavana (BS ’85, MEd ’87, PhD ’94), provided cultural support and translations and guided relations with Samoan officials. And faculty instructed students in the basic skills they’d need to assist the BYU faculty and professional cardiologists and cardiac sonographers.

Following the classroom show, the children, in their bright-colored shirts, lavalavas, and flip-flops, stand in lines leading to the main school hall. At the head of the lines sit BYU students, stethoscopes in their ears. The interns have been taught to identify murmurs, the distinctive whooshes that muddy the “lub-dupp” of a healthy heartbeat.

They direct the children to another line, where they wait for their turn to lie on a table and have a professional sonographer peek inside their heart. Whatever is found, there is good news to share. If signs of RHD aren’t present, the child is sent off to play; if RHD is suspected, then Marv Allen and the other cardiology specialists can provide recommendations on how to halt the damage to the heart valves and, when necessary, seek repairs.

They refer children with disease to Samoan health officials. “Clinicians there are very capable when it comes to treating the disease,” says Allen. “This is a great partnership between the skilled personnel of Rheumatic Relief and the already established infrastructure of the Samoan Ministry of Health.”

Of those diagnosed with RHD, the BYU students ask for a sample of their spit. It’s all in the name of science, they assure, to help beat this disease for future generations.

Changing Futures

The saliva samples make their way back to Provo, and, in John Kauwe’s fourth-story Life Sciences Building lab, an army of undergraduate students works to isolate, sequence, and analyze the DNA. Collaborating with researchers at Oxford University and other institutions, they have conducted the first-ever genome-wide association study for RHD. And in the journal Nature Communications, they recently reported their discovery of a genetic mutation that more than doubles the risk of RHD in Samoans and that also raises the risk for other Pacific Islander populations.

From here, says Kauwe, the goal is to better understand why this variant makes Samoans so susceptible to RHD. It’s information that is vital to finding a way to decrease that risk.

In the meantime, the entire team takes satisfaction in improving children’s lives through education and early diagnosis. And they note the trips’ impact on their own mind and hearts. “You can feel the spirit that accompanies this work,” says Richard A. Gill (BS ’93), a BYU biology professor and advisor to Rheumatic Relief. “Students are richly blessed by the love and graciousness of the Samoan people.”

Premed student Avei says working with Rheumatic Relief has given him “so many opportunities to prepare . . . for a career in medicine.” This December, he’ll travel with Marv Allen to present research on echocardiographic screening at the World Congress of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Health in Dubai. But mostly, he says, he’s grateful for the opportunity to fulfill a promise he made as a missionary—that he’d find some way to serve the Samoan people again.

Intern Thomas M. Knapp (’20), another Samoa returned missionary, agrees. “The people here were my family when I was a missionary,” he says with emotion. “Being able to give back to them is something I always dreamed of. It means the world to me.”

Additional photos can be found at BYU Photo.

Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.