A trip to Ghana gave four illustration students a meaningful BFA project and exposed them—firsthand—to the faith of modern pioneers.

A trip to Ghana gave four illustration students a meaningful BFA project and exposed them—firsthand—to the faith of modern pioneers.

“You want me to go to Ghana?” asked illustration professor Richard D. Hull (BFA ’87), staring at the student in front of him in disbelief. “Why can’t we go somewhere quieter—like Montana? There are nice little landscapes we can paint there.”

But illustration student GayLynn Pettersen Ribeira (BFA ’07) wasn’t giving up. It was the fall of 2005 and she wanted Hull to mentor her BFA illustration project, which would include a trip to Ghana in the spring of 2006. For her project, she wanted to bring to life on canvas the early Ghanaian members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, with the hope of inspiring others through their stories of faith and sacrifice.

After making her case, Ribeira looked resolutely at Hull and said, “You know you’re going to take me, don’t you?”

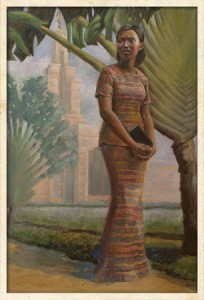

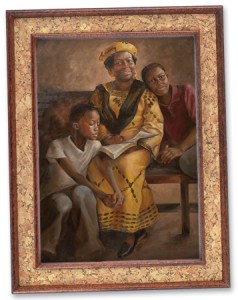

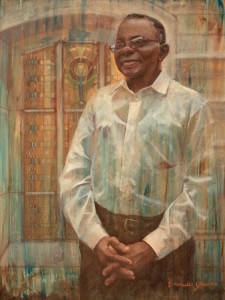

Joseph William Billy Johnson gained a testimony of the Church in 1964 and began preaching the gospel. By the time the first missionaries came to Ghana in 1978, he had established 10 congregations with about 1,000 members. His grandson is among those who flourish in the Church, now well established in West Africa. (Holiness to the Lord, by Emalee Glauser)

Her persistence prevailed. Hull consented, and preparations began. With the help of numerous grants from BYU, three other illustration students—Jesse Bushnell (BFA ’07), Emmalee R. Glauser (BFA ’07), and Angela Nelson (BFA ’07)—eventually joined the project. Ribeira and Nelson, who committed to the trip early on, met with Hull weekly for nearly four months to receive lessons on composition, portraiture style, and paint quality. The other students joined later. “This was far more in-depth than a typical class situation and was geared toward one goal—to portray the Saints through narrative painting,” Nelson says of Hull’s instruction. “This pushed us much farther and harder than any assignment we’d done before.”

The students also prepared by learning about early Ghanaian members of the Church. They used most any resource they could find on the topic, from classes on African culture to lengthy books about the history of the Church in Ghana, recording the names of Saints they wanted to meet and paint.

They planned their nearly two-month trip to include visits to the cities with the highest concentrations of Church members, where they would gather stories, take photographs, and, of course, paint. After months of preparation, the group boarded a plane for Africa.

Accra: Joseph W. B. Johnson

On their first morning, sunlight illuminated the concrete buildings and shanties of Accra, where people cooked on fires near the open sewage running along the streets. Brightly dressed women balanced heavy loads of nuts and mangoes on their heads as they walked the busy streets of the capital city, in southern Ghana. The BYU group walked through the flood of faces, feeling overwhelmed and excited about their new surroundings. Several days later, Hull wrote about his experience taking in the country: “I pray that my painting skills are up to the task. How can my pictures convey the charm, kindness, and beauty of these people?”

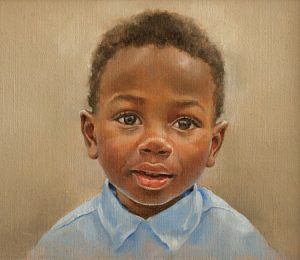

One day about a week after they arrived, Glauser wiped a light drizzle off her brush as she painted on the grounds of the Accra Ghana Temple. A smiling couple approached, asking if she would paint a portrait of their son. The father pulled out a picture of the little boy.

“He looks just like his grandfather,” he said with obvious pride. Looking up from her canvas, Glauser asked who the boy’s grandfather was.

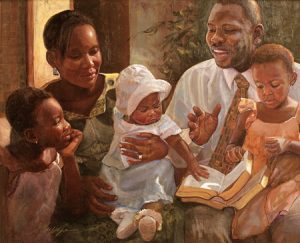

While finding and recording the stories of Ghanaian pioneers, the BYU students also encountered hundreds of everyday Saints who welcomed them into their lives at church meetings and in homes throughout the country. Kuame’s Sunday Nap, by GayLynn Ribeira

“Joseph William Billy Johnson,” the man responded. Glauser knew this name. Johnson is one of the most beloved Saints in Ghana and had been an energetic, though unofficial, missionary for the Church long before the first official missionaries came to the country in 1978.

Glauser was delighted to learn that Johnson, now a stake patriarch, was just around the corner. He was waiting in a car that would take him to the airport, and he would not return to Ghana until after the students had left the country. The couple offered to introduce them, and Glauser quickly found Bushnell, who was nearby.

Stepping out of the car with a warm smile and crooked glasses, Johnson extended his hand to the two young women and thanked them for their service in the Church. He pointed to the temple, saying, “Isn’t it wonderful we have a temple here? I was not sure if I would live to see one in my own country.” Although Johnson had very little time, the students eagerly asked questions and snapped pictures as he explained what it was like to help introduce the gospel to his country.

Before the Church was officially established in Ghana, Johnson had seen the Book of Mormon in a dream and was determined to find out more. After receiving the book from a friend, Johnson went door to door for 14 years, preaching the message within its pages before the missionaries arrived. As his tiny congregation grew, so did persecution from other churches. He promised the early believers that the Church would someday come to Ghana, and he encouraged them to continue worshipping in faith with the knowledge they had. Because of his persistence, the first missionaries to Ghana found hundreds eager for baptism.

That evening, Glauser wrote of the unexpected meeting in her journal: “I began feeling a bit ashamed of myself. Here was this great man. A modern-day Alma the Younger. . . . A man who lives in holiness to the Lord by fully consecrating his life and soul to God, and he was thanking me and showing me love? I have never felt so honored.”

After closing her journal, Glauser sat in a circle with the rest of the group for their nightly meeting. Many of the members had meager incomes, so for the entire trip the group stayed in guesthouses and hotels, which were often full of cockroaches and lacking showers. Sitting on the floor, they planned the following day, held a short devotional, and then took turns sharing the pioneer stories they’d gathered that day. In the mornings, and without formal guides, Hull and the students paired off to interview Saints they’d learned about while attending local meetings of the Church.

As the early Saints continued to come out of the woodwork, Bushnell recalls, “it felt like God allowed us to meet many of the key players who helped the Church to really grow there—the pillars in the past and present. He guided our footsteps from one person to the next.”

Kumasi: Kofi Sosu

After nearly three weeks in Ghana, the group squeezed into a crowded tro-tro (minivan bus) that took them about 150 miles northwest of Accra into the rain forest to Kumasi, Ghana’s second-largest city.

At church in Kumasi, the students met Bishop Kofi Sosu, who consented to share his story. He looked at them closely with his kindly eyes, pausing as if to take the sacred memory carefully off the shelf. He then related what he called a “small, simple story.”

Sosu was baptized as a young adult, despite his parents’ severe opposition. Shortly after he became a member, the government initiated a “freeze” on the Church, forbidding members from worshipping. Sosu tried to show devotion inside his home but was hindered by his parents’ threats to inform the police.

After the freeze ended, Sosu became determined to serve a mission. His parents threatened him again, promising to disown him if he chose to don the suit and nametag for two years. Sosu chose his faith and was renounced by his family.

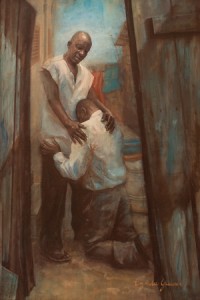

While serving in Nigeria, Sosu sent a letter to his family once a week, but not one was answered. After two years he arrived home with no one to contact but his branch president, who found him a place to stay temporarily. Unsure of where to go next, Sosu prayed and fasted. Despite his apprehension, he felt he should return to his father’s house. As Sosu approached the gate, his father saw him and asked who he was.

“I am your son,” Sosu replied.

“My son?” his father said.

“Yes—your son, Kofi.” Tears came suddenly to his father’s eyes. No longer able to bate his emotions, Sosu’s father embraced him.

“Oh, my son, my son. I am so sorry,” he said, pulling away for a moment to look at Sosu’s face. “I have not had a moment’s peace since I disowned you. I know you did the right thing, and I accept you as my son.”

Cape Coast: Priscilla Sampson-Davis

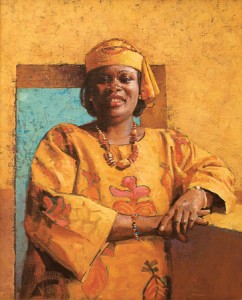

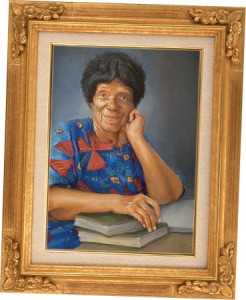

On entering the stucco home of Priscilla Sampson-Davis, the students stepped into the living room to find the first woman baptized in Accra perched on a chair amid her tidy surroundings. She had moved from Accra to become a school principal in Cape Coast—a quiet ocean-side city built on the slave trade during the 1500s.

Sampson-Davis remained poised as she answered the students’ questions and they quickly scrawled notes. She replied each time in a professional but gracious tone, explaining her efforts to strengthen the Church in Accra.

When missionaries first knocked on her door while she was living in Holland, Sampson-Davis eagerly welcomed them in. Her husband hovered in the background, listening with a skeptical ear. Although he did not accept their message, when the family returned to Ghana, Sampson-Davis joined Johnson’s congregation. After finding the gospel, she and her children waited 14 years—until 1978—to be baptized. Soon after, Sampson-Davis became concerned about members in her ward. Many of them could not read the gospel in their own language and remained quiet when others sang the hymns. In a vision, a white-clad figure asked her, “Wouldn’t you like to help your sisters and brothers who can’t read and who can’t join you in singing praises to Heavenly Father?” She questioned her own abilities but answered, “I will try.” She went on to translate several hymns as well as parts of the Book of Mormon and other Church texts into Fanti.

The interview with Sampson-Davis was one of the last evenings the students would spend with a Ghanaian pioneer. During their trip they had completed nearly three dozen such interviews with Church members. Within a week the group was on a plane bound for Utah. Nelson recalls that the words of Sampson-Davis and Johnson and so many other faithful Saints filled her mind on that flight. She looked out the window at Ghana—a place that had become her entire world for nearly two months but now appeared as small and distant as when she had first seen it on a map. She started to cry. “I kept thinking of all the people that had rubbed off on me. . . . They had welcomed us into their homes and made us a part of their families. And because of this, we all went home very different people.”

The Translation to Canvas

Back home with brushes in hand, the students were faced with an even greater challenge than collecting the stories of the Saints in Ghana: rendering those experiences in paint. Other than Hull’s continued guidance, they had only their sketches, photos, journal entries, and memories to work from.

“It was overwhelming to think we were going to portray these wonderful people,” Bushnell says of her paintings. “I wasn’t sure about my capabilities and I often felt inadequate to do these Saints justice.”

Of her experience creating the portraits Glauser says, “I painted hours and hours a day for more than a year, and I paint differently now because of it. I painted many faces over and over again. Some days I’d get so much done and on other days far less, but through this project everything I’ve been learning at BYU finally sunk in.”

At the completion of the students’ BFA project in fall 2007, more than 30 paintings hung in the Harris Fine Arts Center’s main gallery, conveying the spirit not only of the early Ghanaian Saints, but of more than 32,000 Church members now living in the country. Brushes had touched some of the canvases just hours before, and the paint on some of the pieces was still shiny with moisture as they hung at the opening of the exhibit. Standing close to the paintings, some observers became very still, studying the images and lives of strangers. Others allowed tears to fall unrestrained. Time, language, and distance were erased as the faces of Ghanaian Saints told their stories.

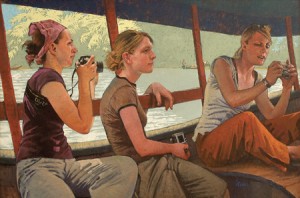

Volta River Tourists, by Richard Hull. Gliding by jungle forests overhanging the water, Angela Nelson, GayLynn Ribeira, and Jesse Bushnell (from left) take in life along Ghana’s Voltra River. Mentored by their professor during nearly two months in the country, the three BYU art students and their classmate, Emmalee Glauser, immersed themselves in new customs and culture to find stories of familiar faith.

“I was grateful that the paintings touched so many people and that we could use our talent to share such an uplifting history,” Ribeira says of the project. “People thanked us for helping them ‘meet’ the Saints of Ghana, and that is ultimately what we wanted.”

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.