By Julie Walker

Whether sitting cross-legged on the floor of a Nigerian hut or working at a Jordanian clinic, Rogers willingly serves on the front liens of conflicts that endanger both body and heart.

The face of poverty is something most of us see only under controlled circumstances: We drive by a stranger on a street corner or see a pitch for “Save the Children” on a TV screen. For the most part, we keep such images a comfortable distance from our hearts and our homes.

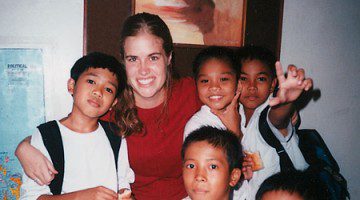

But to Sandra Rogers, dean of BYU’s College of Nursing, the battle against poverty and disease is much more personal–as real as the smiling faces in her office photos. These images of friends she has met in nursing endeavors around the world are reflections of a vast brother- and sisterhood–reflections of bonds that transcend culture, language, and geography.

“When you are personally involved in this type of work, I think it puts a face of a brother or a sister on the circumstances, which is, for me, very important,” Rogers says. “They’re not a statistic, not a newsreel. I’ve been where they live, and I have held them or talked to them. It makes them real, not an abstract concept. And the other thing it does is make me real. They know me, and hopefully that makes a difference as well.”

Whether she is sitting cross-legged on the floor of a Nigerian hut or working at a Jordanian clinic, Rogers has willingly served on the front lines of conflicts that endanger the body as well as the heart. Her nursing work in the Philippines, Nigeria, Jordan, and Romania has taught her of the interconnectedness of our health crises and of the need to prepare nurses to deal compassionately with human issues.

“Being sensitive about other people’s suffering and needs has been regarded as something that people were just born to do. People believe you can’t teach compassion,” Rogers says. “But I have found that if we can place students in circumstances where they can be guided to understand the many factors that influence a patient’s decisions, then the student understands that human beings are complex people who operate in complex worlds.”

Regardless of whether they will work in Utah or Uganda, nursing students need exposure to different cultures, Rogers believes. So when the nursing curriculum underwent a major revision in 1995, she was a key proponent for establishing a cross-cultural training program. The program now allows students to work in Guatemala and Jordan and with Native Americans in Arizona and Utah.

“We see our nursing students as people who will need to provide appropriate care for a very diverse population here in the United States, and we see them occupying positions in the Church, which also has a diverse membership,” Rogers says.

“We want to try to provide them with opportunities to learn, work with, appreciate, care for, and be interested in people whose life experiences haven’t been exactly like theirs.”

With a curriculum that was already crowded–and pressures to meet the demands of the industry and the university–there was some initial skepticism about the feasibility of a cross-cultural program. Yet the revised program is receiving positive feedback from faculty, students, and graduates as well as from others. The National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission recently gave the college a full eight-year continuing accreditation, giving high marks for the elective experiences and the broad range of diverse experiences offered to nursing students.

While industry recognition is gratifying, Rogers admits that the college’s development-oriented work is aimed at even larger university and Church objectives, grounded in the directive to “enter to learn” and “go forth to serve.” Nursing students receive continual reminders of their role as healers. They begin each semester singing the LDS hymn “Lord, I Would Follow Thee,” paying special attention to the words, “I would be my brother’s keeper, I would learn the healer’s art; To the wounded and the weary, I would show a gentle heart” (Hymns [Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1985] no. 220).

Rogers’ own background in the nursing profession has spiritual roots, including service as an LDS welfare missionary in the Philippines. After receiving a bachelor’s degree from BYU and a master’s from the University of Arizona, she pursued a doctoral degree at the University of California, San Francisco. Living in Nigeria for a year, she evaluated nursing programs and their integration into the country’s health-care system, characterized by frequent political upheaval and economic hardship.

Rogers has continued to be involved in the Nigerian health-care system. In 1989, when she saw that educators were using outdated medical texts in teaching, she organized a book drive and sent a shipment of 26 crates of new or nearly new medical reference texts to the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital. When she returned in 1996 to speak at the 25th anniversary of the school, she saw that the donations formed the bulk of the nursing library.

As she talks about life in Nigeria, Rogers says she learned many lessons from the everyday heroes she encountered there. She accompanied a Catholic nurse who “built the Lord’s kingdom through patient, joyful service to a small leper colony” and observed the work of another nurse who spent weeks teaching a poor widow how to buy food and feed her family. She remembers well the rebuke a Nigerian nurse gave her colleagues when they were more concerned about receiving recognition than serving others. “There’s good enough for all of us to do without worrying about who takes credit,” the nurse said.

“I can’t think of a gospel principle that hasn’t been amplified or reinforced by my experiences with these people in terms of faith, hope, and charity and doing good and seeking after every good thing,” Rogers says. “My work has taught me the importance of a person’s heart, and I have learned how much people love God when they know him.”

It was also in Nigeria that Rogers was exposed to heartbreaking poverty. In one case, she was overwhelmed by the generosity of a family that had not eaten for two days but that provided bottles of soda for their guests, a gift that could not be refused. Rogers wrote of the experience:

“I drank very little and handed the bottle to the children because I was weeping so much I could not swallow. Every part of me ached with concern for this family and thousands like them, a concern that could only be communicated through my tears because I had no other language.”

Rogers’ reaction to the family’s plight also touched their lives. The woman told Rogers’ Nigerian colleague,”If a white woman can cry with a black one, then maybe there is some hope for the world” (Sandra Rogers, “Stones, Swords, Seeds, and Tears,” Brigham Young Magazine 48, no. 4 [November 1994], p.35).

Such experiences and the generosity of kind and hospitable people worldwide have also given Rogers reason to hope and to work harder. “I have had people who have nothing give me everything they have. There are tremendous feelings of obligation that go with that,” she says.

Rogers has also been involved in numerous Church- and government-sponsored projects. She worked in Romania as a member of an LDS Church Humanitarian Services team. She also evaluated nursing education programs in Jordan as part of a $12 million six-year USAID project.

Because the issues that impact health care are so complex and are subject to the whims of prevailing powers, Rogers says she has become convinced that the infrastructures and insurance programs are only part of the equation. She feels the only change that will have any real, lasting impact on world health is a transformation of hearts.

“We have a situation in the world today where the hearts of men are a little colder so we see a lot more suffering,we see a lot more struggle in the lives of people. I have become convinced that the best political, social, and cultural public health and development strategies are doomed when administered without moral insight and character,” she says.

“We have a situation in the world today where the hearts of men are a little colder so we see a lot more suffering,we see a lot more struggle in the lives of people. I have become convinced that the best political, social, and cultural public health and development strategies are doomed when administered without moral insight and character,” she says.

It has become apparent, says Rogers, that money alone will not solve the complex problems that impact world health care. For example, while the United States spends more money on health care than any other country, its health statistics lag behind those of other industrialized countries. “In our country, we have an infant mortality rate that matches Jamaica. If we were to compare our minority populations, our statistics would be worse.

“There’s a zip code in inner-city Salt Lake where the infant mortality rate looks like an African nation. In this particular zip code, if you were a child, you’d have a better chance of being immunized if you lived in Nigeria than if you lived in Salt Lake City.”

In using such statistics, Rogers hopes to make the point that one doesn’t have to board a plane for Africa to find opportunities for service.

Rogers admits it can be discouraging to see the widening gap between rich and poor both home and abroad. Why does one corner of the kingdom nibble on white bread and bologna while others feast on prime rib and rolls? She struggles with the core issues but looks inward for solutions.”I’m like the guy in The Music Man who always believes there’s a band,” she says with a laugh. “I think I have optimism tempered by reality, but I refuse to lose hope.

“The gospel teaches us about meeting our needs and sharing with others and looking at life as brothers and sisters, having some sense that the children who suffer in Nigeria are somehow connected to us. I believe the Lord expects us to learn how to care for one another, that this is one of our tests.”