By Charlene Winters

NOTE

Much of the information for this article came from the book

prepared to accompay BYU’s Maynard Dixon exhibition:

Linda Jones Gibbs, Escape to Reality: The Western World of Maynard Dixon

New York art historian Linda Jones Gibbs, ’73, has taken an academic approach in the Maynard Dixon art exhibition she curated for BYU’s Museum of Art. But, she says, her fondness for the western artist’s work is separate from the critical analysis she has applied to his paintings.

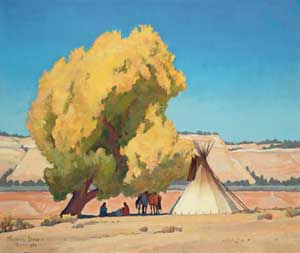

“Scholarship aside, I like so many others am an unabashed fan of Maynard Dixon’s work,” Gibbs explains. “Since childhood I have loved Native American culture, and Dixon’s images of Native Americans in the Southwest are awe inspiring. When I was a student at BYU 25 years ago, Dixon’s Lazy Autumnhung over my work table in the BYU Art Department. I fell in love with his art then and there.”

She is not the only person enamored of Dixon’s western vision. “Among those on the inside of the pictureby that, I mean professional artists, museum curators, and art scholarshe is loved, respected, and admired,” says Vern Swanson, ’69, director of the Springville (Utah) Museum of Art. “In my opinion he understood the western landscape better than anyone else.”

The BYU exhibition, Escape to Reality: The Western World of Maynard Dixon,reflects Dixon’s desire to find spiritual revitalization and artistic inspiration in the desert Southwest. He frequently referred to these remote, untamed regions as “the real thing,” and his goal as an artist was to get as close to the real thing as possible.

Though Dixon (18751946) is best known for his paintings of southwestern landscapes and Native Americans, he also created compelling images of the Great Depression and victims of social unrest. Both are included in the museum’s comprehensive Dixon exhibition that opened for a yearlong run on Oct. 26. It showcases BYU’s unsurpassed collection, as well as 22 additional pieces on loan, and is the first time BYU’s original collected works have been displayed in their near entirety.

Western Poetry and Pathos

Born in 1875 in Fresno, Calif., Dixon made the first of his continuing journeys from California to the Southwest in the summer of 1900. He worked as a magazine and newspaper illustrator in San Francisco and a commercial illustrator in New York City, but he resented creating melodramatic imagery for publication, and in 1912 he returned west, where he spent the remainder of his prolific career.

Dixon saw himself as a true westerner. As Gibbs explains, “He strolled the streets of San Francisco near his studio wearing a wide-brimmed black Stetson hat, hand-tooled cowboy boots, and a Navajo silver belt. One could apparently hear him coming from the faint buzz of the rattle from a rattlesnake skin attached to his rawhide hat band and the tapping of his ebony cane tipped with silver, the handle of which was engraved with his thunderbird logo” (Linda Jones Gibbs, Escape to Reality: The Western World of Maynard Dixon[Provo: BYU Museum of Art, 2000], p. 10).

For nearly half a century, Dixon captured the arid landscapes of southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, and Utah. As he sketched and painted remote regions of the country, he often said his mind was set to tell the truth about this western world.

One work in the BYU exhibition, Round Dance,a 1931 oil on canvas, characterizes his poetic, even mystical, interpretation of the Indian as a symbol of simpler times. While living in an old adobe house in Taos, N.M., he witnessedon Christmas Eve 1931a traditional Native American social dance and painted his observations. “In this closely cropped image . . . figures on both sides of the picture plane are cut off,” says Gibbs, “giving the viewer a sense of their slow, deliberate movement. The participants, physically connected and moving in unison, personify what many outsiders saw as a communal soul” (Gibbs, Escape to Reality,pp. 103105).

Lazy Autumn, oil on canvas, 1943. American painter Maynard Dixon sought to interpret the “poetry and pathos” of western people.

This work and others underscore Dixon’s desire to dignify Native American culture at a time when the U.S. government was attempting to “civilize” and assimilate Native Americans into the white culture. Banning dances was one government restriction, and this rule was still officially intact when Dixon painted Round Dance.Indians were allowed to dance at home only on certain holidays, including Christmas, when this painting was done.

“Dixon chose not to address the poverty and disease rampant among the Indians,” Gibbs explains. “It was an era where government agencies were wresting children from their homes and putting them into boarding schools, were cutting their hair and putting them into the white culture’s clothing. There was a horrible scenario going on among the native people that Dixon doesn’t paint. In his images Native Americans were most often depicted in contemplative postures within a natural setting or participating in a communal activity such as a ceremonial dance.”

Yet Dixon was aware of the challenges faced by the people he painted. After visiting the Hopi Indians in 1923, he explained his philosophy by writing, “Many people . . . might see only that these Indians are poor and dirty . . . that the kids go naked. . . . But when you see one of their ceremoniesthere for an hour something fine flashes out clear; there is savage beauty in them. . . . They have dignity and form. . . . In these later canvases you will probably see traces of all this. There is something of magic in it, and legends endow it with strange meanings. The imagination moves free and the past and present are one. So the visions of the old days have been as important to my work as things actually seen” (Maynard Dixon to Robert MacBeth, from Walpi, Ariz., 1922; Maynard Dixon Collection,Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley).

Even though Dixon sought to reject sentimental images of the West, he in fact created his own romantic view, attempting, as he said in 1921, “to interpret . . . the poetry and pathos of the life of western people, seen amid the grandeur, sternness and loneliness of their country” (quoted in Anthony Anderson, “In the Realm of Art and Artists,” Palette and Brush, Los Angeles Times,Jan. 12, 1913, p. 4).

Much-Loved Art

Although BYU’s holdings represent much of Dixon’s career, Gibbs has added more examples of his Native American art for the exhibition. As she attempted to collect them, however, she discovered how much their owners loved them.

“This art was a challenge to come by because people simply did not want to be parted from it,” she says. “In the western United States especially, the Maynard Dixon following is growing at a phenomenal rate, and most of his important works are in private hands. They have become a precious commodity that is not so much an investment as a possession. People hang Dixon paintings in their homes because they love them, and some people flatly refused to let me exhibit their personal works. They said they would simply miss them too much.”

Not everyone, however, admires Dixon’s style, Swanson says. “Dixon offers a more intellectual taste than what most western art gives you. Many uninitiated patrons at first do not like his highly abstracted, dry surfaces. It is not the country or cowboy art they expect. They think his work should be more detailed and narrative, so they miss a sumptuousness that isn’t done with varnish or transparent colors. Some even think his stylization is actually archaic.”

Swanson encourages first-time viewers to come back. “Maynard Dixon can’t be taken in all at once,” he explains. “If his work were food, it would be vegetables, not dessert. He offers roughage for your aesthetic diet. Dixon is substantial and real, all right, but he takes a little work. I believe anyone who really gives Dixon a chance will certainly come to like, if not love, Maynard Dixon’s art.”

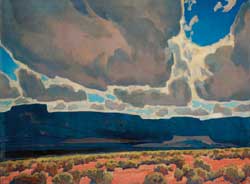

Mesas in Shadow, oil on canvas, 1926. A true westerner, Maynard Dixon found inspiration in the untamed desert Southwest.

In the ongoing and escalating affection for Dixon, many of the writings about the artist take a biographical “great man as artist” approach. By contrast, BYU’s exhibition will focus on the art instead of the artist.

“While Dixon’s physical bearing, his attire, and the decor of his studio enhanced his claim to depict the ‘real’ West,” Gibbs says, “such trappings cloud the power of his art. We will provide enough information about Maynard Dixon to provide a context, but we are not so concerned that he was a lanky, gruff guy who wore a cowboy hat and wrote poetry as we are about what his art says to us. Rather than using anecdotes of his personality, we are examining the actual images to see what they have to tell us about an entire era and an entire mind-set.”

“Our intention is to avoid adding to the mythology of Maynard Dixon as the quintessential western artist,” says Campbell B. Gray, director of the BYU museum. “Other people have already provided a rich understanding of his personality and personal history. We hope the exhibition will challenge thinking and prompt inquiry as part of a collaboration between the exhibition and the museum-goer.”

A Window into the Psyche of America

While Dixon’s southwestern landscapes and Native American portraits will be featured prominently in the exhibition, his haunting Depression-era works are most likely responsible for BYU’s large collection of Dixon art. More than 60 years ago, those paintings caught the eyes of Herald R. Clark, an economist and dean of the BYU School of Business. Clark admired Dixon and made an unannounced trip to San Francisco in 1937, hoping to meet Dixon and bring his art to the university. When Clark asked Dixon if he would permit BYU to acquire examples of his work, the artist allowed the university to select and purchase 85 paintings and drawings that spanned almost his entire career. In the ensuing years, the university has collected additional Dixon artworks, and with more than 100 pieces, BYU maintains the largest Dixon collection in the world.

Dixon’s Depression-era art still commands attention. As a way of highlighting its collection, the BYU museum makes postcards of the most imporant works in its collection, including those of Maynard Dixon. One of them, Forgotten Man,has sold out. “We made 2,000 of them, and they are gone,” says Dawn Pheysey, ’66, a BYU art curator assisting with the show. “Students ask for that postcard all the time. Somehow it speaks to them.”

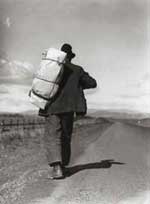

Forgotten Man, oil on canvas, 1934. One of his many Depression-era paintings, this work was inspired by homeless wayfarers Dixon saw while traveling from New Mexico to California.

Forgotten Man,a 1934 oil on canvas, was painted after Dixon and his wife saw many homeless wayfarers as they traveled from New Mexico to California. This painting depicts a lonely transient on the curb of a busy city street. “The pathos of the scene is enhanced by the painting’s somber tones as well as its cropped composition, which allows us to see only the legs and shoes of the heedless passersby,” wrote Gibbs in a description of the work for the museum’s permanent exhibition, 150 Years of American Painting. “Not only are the faces of the crowd unseen, but the visage of the forgotten man is downcast and lost in shadow. As in Round Dance,the viewer is given a front-row seat, so to speak, to the scene at hand, sharing a proximity to the figure without peripheral distractions” (Linda Jones Gibbs, 150 Years of American Painting [Provo: BYU Museum of Art, 1994], p. 156).

As Dixon captured the Depression on canvas, his second wife, photographer Dorothea Lange, captured it on film; 40 of her photographs compose an exhibition displayed in the BYU museum in tandem with her husband’s work. “We will look at both artists equally and see how they influenced, encouraged, and fed off of each other,” says Pheysey. “Dorothea Lange, for instance, really encouraged his Depression-era images that were painted during their 15-year marriage. She, in turn, became known for her documentary work of the Great Depression.”

The images created by the two artists represent a cultural and historical era. “You could say Dixon was a pivotal painter of the Depression as much as Woody Guthrie was a pivotal singer of the Depression with his anthem ‘This Land Is Your Land,'” Swanson says.

Round Dance, oil on canvas, 1931. Rejecting common prejudices on his day, Dixon was fascinated by the dignified simplicity he saw in Native American culture.

Dixon’s images, for example, can open a window into the psyche of America at a specific time. In the early decades of the 20th century, a wave of artists and writersincluding Dixondisillusioned with materialism and other ills of industrial society, sought artistic refuge in a place where humans seemed to have remained in touch with the earth, with themselves, and with each other. “His works teach history, not so much in providing specifics about historical facts but in guiding us to understand what drove Dixon and so many people like him into the Southwest at the turn of the century,” says Gibbs.

Beyond the historical perspective, however, Dixon’s paintings offer an escape that extended through the world wars and continues today, says Gibbs. “In 1940 an art critic for the Los Angeles Timescounseled his readers, ‘If world war jitters have got you down, drop into the Biltmore Salon . . . and see the great Southwest through the eyes and temperament of the desert’s foremost pictorial interpreterMaynard Dixon.’ Now, decades later, we are at the turn of yet another century wrought with new tensions. Dixon’s paintings continue to function as a therapeutic escape valve” (Gibbs, Escape to Reality,p. 9).

Migrant Worker on California Highway, June 1935. The moving Depression-era photography of Dorothea Lange, Dixon’s second wife, accompanies her husband’s exhibit at the Museum of Art.

Dixon landscapes are not what people would call picturesque, Gibbs points out, but they signify what he found to be beautiful. “He did not paint green trees and lakes or the things we would consider pretty landscapes. What we find are intriguing empty landscapes that allow us to go into them and dwell mentally and think and ponder. When we consider why particular landscapes are so moving for people, it might be related to his incredible way of organizing form. Maynard Dixon was a phenomenal draftsman in terms of his composition. When you look at Cloud Worldwith the clouds moving across the sky, or Round Dance,where he pulls us right into the middle of the circle, we become part of the experience. The way he constructed space is commanding. His landscapes are not photographic. Rather, he combined views and shifted things to arrange them to his liking. It is ironic that we think of his open freedom of the range, yet his images were very controlled. He decided how to place that mountain and where our perspective would be.”

Ultimately, Dixon’s goal was to touch his viewers emotionally with his landscapes and scenes of the city. And many have found inspiration from the provocative sun-, rock-, cloud-, and desert-scapes. “After more than a decade of living on the East Coast (and maybe because of it),” says Gibbs, “I am still enthralled by Dixon’s art. I have had the experience many times of driving through the western landscape only to find myself immersed in a ‘Maynard Dixon sky’that deep, intense, unvarying blue, dotted with uniform cloud shapes that appear to be silently and endlessly marching across a flat horizon. Even with the actual landscape within my view, I would envision and remember what Dixon had seen. It is during instances like thesewhen works of art become so compelling that they actually transform the way we see the world, when life begins to imitate art and not the reversethat one comes to realize and fully appreciate the potency of an artist’s vision” (Gibbs, Escape to Reality,p. 15). ![]()