IN

Ernest L. Blumeshein, The Gift (1922), SAAM, bequest of Henry Ward Ranger through the National Academy of Design.

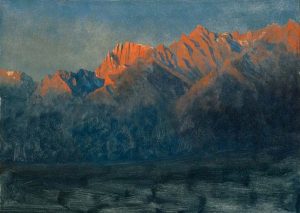

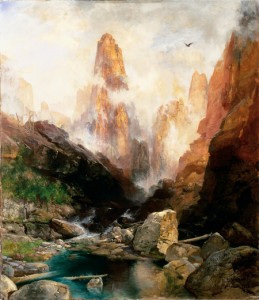

1871 a young artist named Thomas Moran accompanied a U.S. Geological Survey expedition charting the Wind River and Yellowstone country of Wyoming. For him this was a life-altering experience. For the next four decades, he dedicated his life to conveying the wonder and majesty of the Western landscape through his paintings. Moran’s works and those of Albert Bierstadt, another young survey artist, brought to life the great Western wilderness for millions of Americans.

Moran’s and Bierstadt’s works continue to inspire people the world over, and this spring some of their paintings—together with works from 30 other artists—will be on display in BYU‘s Museum of Art. From Jan. 17 through May 18, the museum will host Lure of the West: Treasures from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, an exhibition of 70 works that encompass more than a century of art, moving from the excitement of exploration to the growth of a national mythology about the West.

“First explorers and trappers, then settlers and immigrants were drawn to the lands and opportunities for a new life in the American West,” says Elizabeth Broun, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. “Artists were quick to discover new and exciting subjects in the vast wilderness, mountains, and prairies, as well as in the native and Hispanic peoples who lived beyond the Mississippi River.”

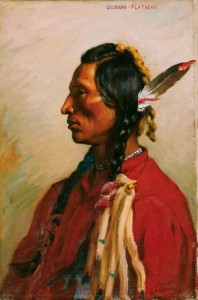

The earliest work in the exhibition dates to 1821, when Charles Bird King created a portrait of five Pawnees in his Washington, D.C., studio. The delegation of Indians had traveled east to negotiate territory rights for its tribe. Wearing wampum ornaments, red face paint, bead necklaces, and fur robes, the figures are noble representatives of a sovereign nation.

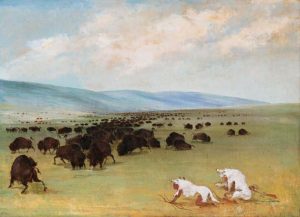

In the early 1830s George Catlin followed the path of explorers Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, traveling up the Missouri River into the Dakota Territories. A group of 18 Catlin works—portraits of Native Americans and scenes of Plains Indian life—forms the exhibition’s centerpiece. These works were part of Catlin’s “Indian Gallery” of approximately 500 paintings that he exhibited throughout the eastern United States and in the capitals of Europe, inspiring a wave of interest in the American frontier and Indian cultures.

Poor Crane, Ya-Tin-Ee-Ah-Wits, Chief of the Cayuses (1891), gift of Alison Warner Waterman in memory of her mother, Frances D. Warner.

Artists’ fascination with the West mirrored the nation’s determination to settle the continent coast to coast. Charles Christian Nahl and August Wenderoth followed the rush to California when gold was discovered there in 1848. Unsuccessful at mining, they turned to recording the life of the forty-niners in paintings such as Miners in the Sierras (1851–52). To illustrate the concept of Manifest Destiny, Emanuel Leutze depicted explorers and settlers heading west in his 1861 oil study for a mural in the U.S. Capitol.

Bierstadt’s three works in the show include his 10-foot-wide masterpiece Among the Sierra Nevada, California (1868). These paintings complement two works by Bierstadt in BYU‘s permanent collection: Salt Lake City, Wasatch Mountains, Uinta Range (1881) and Near Salt Lake City, Utah (1881).

The exhibition also includes works by Joseph Henry Sharp, Eanger Irving Couse, Walter Ufer, and other members of the Taos School, which began informally when East Coast artists visited the Southwest in the 1890s. The exhibition’s three paintings by Sharp show Indians reviving old ceremonies and maintaining craft traditions, which were soon to become part of a new “lure of the West” for a thriving tourist industry. Couse’s life-sized Elk-Foot of the Taos Tribe (1909) presents a wise leader of a native people. Ufer’s Callers (about 1926) imparts a domestic tranquility to Indian life.

“These works give us the opportunity—and I think it’s an important opportunity—to examine how the West has been imaged by the artists,” says Marian Eastwood Wardle, ’73, the Museum of Art’s in-house curator for the exhibition. “Through their works, they have created expectations in us as viewers of how the West should be, so Western landscapes and American Indians look more real to us when they look like these paintings.”

George Catlin, Catlin and His Indian Guid Approaching Buffalo Under White Wolf Skins (1846-48), SAAM, gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr.

To encourage discussion about perceptions created by art, the museum will sponsor a symposium, “Passion for Place: Art and Tourism in a Multicentered Society,” March 7–8.

INFO: Lure of the West runs Jan. 17– May 18 at the BYU Museum of Art; admission is free. For more information call 801-378-ARTS (2787).

WEB: Preview the exhibition online at nmaa-ryder.si.edu/t2go/1lw.