BYU researchers bridge the gap between the ivory tower and the marketplace.

When Scott D. Sommerfeldt dreamed of becoming a world-class acoustic physicist, his thoughts centered on algorithms and anechoic chambers, not such unprofessorial ideas as start-up companies and royalties. But Sommerfeldt, like many BYU scientists, has found his ivory tower endeavors of more use to the real world than he imagined. His noise-cancellation research could soon reduce the whir of your computer fan to a whisper. If you happen to be a heavy-equipment operator, his innovations could make the cab of your backhoe so quiet you might think you’re driving a Miata with the top down.

Sommerfeldt (BM ’83), a professor of physics and astronomy, is one of about 150 BYU scientists whose research has yielded inventions that businesses want to grab and run with in the marketplace. An international fan manufacturer wants to license Sommerfeldt’s technology to reduce fan noise, while Caterpillar hopes to use it in its tractor cabs.

Sommerfeldt (BM ’83), a professor of physics and astronomy, is one of about 150 BYU scientists whose research has yielded inventions that businesses want to grab and run with in the marketplace. An international fan manufacturer wants to license Sommerfeldt’s technology to reduce fan noise, while Caterpillar hopes to use it in its tractor cabs.

Luckily, professor-inventors like Sommerfeldt don’t have to get an MBA to handle the business side of their inventions or a law degree to make sure their ideas are protected. BYU’s Office of Technology Transfer manages all that for them. Director G. Michael Alder and his colleagues promote dozens of innovations each year, from pioneering digital-hearing-aid technology to yogurt spiked with carbonation.

When technology transfer works, society gets valuable, life-improving products, the economy gains jobs, companies garner revenue, and both the inventor and BYU share in profits. Successful products that BYU researchers have sent into the marketplace include revolutionary chemical-analysis instruments, tiny remote-controlled reconnaissance airplanes, and a compound that cures most cases of one form of leukemia.

Despite its modest overall funding for research, BYU regularly places among the top three U.S. universities for the number of start-up companies per research dollar. In 2002 it was first.

Bringing Ideas into the World

BYU’s first quasi-technology-transfer deal took place in the late 1970s. Microbiology professor Marcus M. Jensen, now emeritus, developed a vaccine against turkey cholera that dramatically reduced the mortality rate of young turkeys. He licensed his vaccine to the Schering-Plough Corporation, and when the vaccine became a big moneymaker, Jensen thought the university should share in the profits. Though he didn’t have to, he suggested a legal agreement. He shares his royalties to this day, as does Schering-Plough, even though it is not legally required to do so.

Few technology-transfer deals occurred at any university before 1980 because by U.S. law the government retained all rights to technologies that emerged from research it funded, which was almost all university research.

But in 1980 new legislation allowed universities to keep all commercial rights and share royalties from their patents with inventors. Universities soon began setting up technology-transfer offices.

Since its creation, BYU’s Technology Transfer Office has been charged with tracking inventors on campus, evaluating potential patents, supervising patent attorneys, and licensing patent rights to companies—either to existing companies or to new start-up companies. The new or existing company then transforms the technology into a product and markets it to the world.

BYU’s system stands out from those of other schools for its profit-sharing structure. Most universities give one-fourth to one-third of royalties to faculty, while BYU gives 45 percent. BYU also has an unusual policy that says if faculty are willing to put their royalties into their research account, BYU will match the amount from its share of the revenue. A large number of inventors choose this option. Alder says this generous profit-sharing model is one reason BYU has such an impressive record of technology transfer in proportion to its research dollars.

Lynn Astle, recently retired director of Technology Transfer at BYU, says the university’s philosophy views technology transfer as a service to faculty rather than as a profit center. “We made it our mantra that we do some things for money, but never just for money,” he says. “We’ve still done well with respect to money, so you get rewarded when you do things for the right reasons.”

He says their main goal is to help bring great ideas into the world. “These faculty have been ‘pregnant’ with their baby for five or 10 years, and they don’t want to tuck the baby into a closet,” says Astle. “Our main job is to get what they’ve done out into the public and see it used.”

Technologies Transferred

So far the Technology Transfer Office has shepherded 78 technologies through the patent and licensing process, generating a total of $36.8 million in income. According to Astle, one of the most successful technologies is water-modeling software developed by professor Norman L. Jones (BS ’86), associate professor E. James Nelson (BS ’89), and associate research professor Alan K. Zundel (BS ’88) in the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department. The software, licensed to start-up company Environmental Modeling Systems, is used in more than 100 countries to predict how water will behave in different scenarios, such as where and how fast a toxic spill will spread in a river. It has become the world standard in its field.

Astle says another highly successful license is for a drug that literally cures most cases of a rare cancer called hairy- cell leukemia. The compound was synthesized decades ago by chemistry and biochemistry professor Morris J. Robins when he was a graduate student at Arizona State University. The synthesis was improved at BYU by his late second cousin, chemist Roland K. Robins (BS ’48), then patented and licensed to pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson. Morris Robins later joined the BYU chemistry faculty and further improved the synthesis. According to the Web site hairycellleukemia.org, Robins’ drug, 2-chlorodeoxyadenosine, is the “current treatment of choice” for the disease, sending the cancer of 85 to 95 percent of all sufferers—about 800 a year—into remission without the typical chemotherapy side effects of hair loss and nausea. The drug also is used for treatment of other types of cancer and is under investigation with additional diseases.

“It’s a nice little niche drug that is extremely nontoxic,” says Astle. “It has saved a lot of lives.”

One of the most promising new technologies from BYU is an antibiotic developed by chemistry and biochemistry professor Paul B. Savage (BS ’88). With the medical world extremely concerned about bacteria that are rapidly mutating to resist known antibiotics, creating an antibiotic that prevents such resistance would be revolutionary. By imitating the chemical structure of natural antibiotics, Savage may have found just such a groundbreaker. His synthetic antibiotic molecules, called cationic steroid antibiotics, are smaller than other antibiotics, making them easier and less expensive to generate.

“We have shown quite conclusively that we have the same antibacterial activity as natural antibiotics even with our small molecules,” says Savage. In fact, his compounds go a step further than natural antibiotics. Bacteria produce enzymes to wage chemical warfare on the antibiotics trying to kill them, and these enzymes will chew up the natural antibiotics. But Savage’s compounds, he says, “the bacteria can’t touch. They come in and kill bacteria very rapidly. They will kill bacteria that are resistant to all other types of antibiotics.”

A Denver company called Ceragenix has licensed Savage’s compounds and is doing preclinical trials, which will lead to the longer and more expensive human clinical trials in the near future.

Thanks to assistance from the Technology Transfer Office, Savage’s work and that of dozens of other professors is moving beyond the world of laboratories and academic journals and into the lives of people around the world.

“As a professor I don’t have the time to go out and get the necessary capital to get the testing done,” says Savage. “This is the only way these ideas can get out of my laboratory to benefit people.”

Sue Bergin teaches writing in the BYU Honors Program.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

Fruits of Faculty Labors

BYU has licensed dozens of technologies developed by faculty to existing companies or new start-up companies. Here is a sampling.

Digital Hearing Aid

Digital Hearing Aid

Developed by electrical and computer engineering professors Douglas M. Chabries and Richard W. Christiansen.

Licensed to start-up company Sonic Innovations (Salt Lake City).

What it does: This hearing aid amplifies sound using a process that imitates the human nervous system.

Thin-Film X-Ray Window and X-Ray Detector

Thin-Film X-Ray Window and X-Ray Detector

Developed by professor David D. Allred (BS ’71) and professor emeritus Larry V. Knight (BS ’58), both of physics and astronomy; James M. Thorne, professor emeritus of chemistry and biochemistry; and Raymond T. Perkins (BS ’75).

Licensed to start-up company Moxtek (Orem, Utah).

What it does: These technologies are used in electron microscopes to more precisely detect chemical compositions.

Water-Modeling Software

Developed by professor Norman L. Jones (BS ’86), associate professor E. James Nelson (BS ’89), and associate research professor Alan K. Zundel (BS ’88), all of civil and environmental engineering.

Licensed to start-up company Environmental Modeling Systems (South Jordan, Utah).

What it does: This software is used worldwide to predict how water will behave under different circumstances.

NanoParticle Production

Developed by chemistry associate professor Brian F. Woodfield (BS ’86) and professor Juliana Boerio-Goates.

License pending with start-up company Cosmas (Provo).

What it does: This new method for producing ultra-high-purity metal-oxide and mixed-metal-oxide nanoparticles is less expensive and has higher production yields than previous methods.

Friction-Stir-Welding Technology

Developed by mechanical engineering associate professors Tracy W. Nelson and Carl D. Sorensen (BS ’81), along with Scott M. Packer (BS ’86).

Licensed to MegaStir Technologies (Bountiful, Utah).

What it does: New technology for friction stir welding—which allows metals to be joined without melting—permits the process to be used for alloys with high melting temperatures.

Autopilot Technology for Unmanned Air Vehicles

Autopilot Technology for Unmanned Air Vehicles

Developed by associate professor of electrical and computer engineering Randal W. Beard and associate professor of mechanical engineering Timothy W. McLain (BS ’86).

Licensed to start-up company Procerus Technologies (Vineyard, Utah).

What it does: Lightweight hardware and sensors coupled with ground-control software make it possible to fly small un-manned air vehicles either autonomously or semi-autonomously and receive live video feedback. These can be used in surveillance and reconnaissance applications.

IsoTruss

IsoTruss

Developed by professor of civil and environmental engineering David W. Jensen (BS ’80).

Licensed to IsoTruss Structures (Brigham City, Utah) and Tauruss (Tokyo).

What it does: IsoTruss uses a composite material in geometric patterns to create extremely rigid and light structures for such applications as transmission towers, beams, and bicycle frames.

2-Chlorodeoxyadenosine (2Cda)

Developed by Morris J. Robins, professor of chemistry, and Roland K. Robins (BS ’48), professor emeritus of chemistry.

Licensed to Johnson & Johnson (New Brunswick, N.J.).

What it does: The preferred treatment for hairy-cell leukemia, this drug sends the cancer of most patients into remission with minimal side effects.

Whole Blood Platelet Aggregometer

Developed by professor of chemical engineering Kenneth A. Solen and colleagues at the Utah Artificial Heart Institute.

Licensed to Thrombodyne (Salt Lake City).

What it does: This instrument allows doctors to quickly evaluate whether a patient is responding to certain medications as expected.

Near-Field Active Noise Suppression

Near-Field Active Noise Suppression

Developed by Scott D. Sommerfeldt (BM ’83), professor of physics and astronomy.

License is being negotiated with an international fan manufacturer; optioned by Caterpillar (Peoria, Ill.).

What it does: This technology creates sound waves to actively cancel noises.

Hand-Portable Ion-Trap Detector

Developed by chemistry professor Milton L. Lee.

License pending with start-up company Palmar Technologies (Provo).

What it does: A portable device to detect low levels of chemical and biological substances, this technology could be used in security, food-safety, and pollution-control applications.

Sparkling Yogurt

Sparkling Yogurt

Developed by professor of nutrition, dietetics, and food science Lynn V. Ogden.

Licensed to a U.S. food company.

What it is: Lightly carbonated yogurt.

Cationic Steroid Antibiotics

Developed by Paul B. Savage (BS ’88), professor of chemistry.

Licensed to Ceragenix Pharmaceuticals (Denver).

What it does: These synthetic antibiotics are being tested for treating a broad spectrum of bacterial infections and for coating implantable medical devices.

Putting Creativity to Work

Putting Creativity to Work

While the Technology Transfer Office conveys scientific advances into the business world, a second office at BYU transfers to the marketplace “content” products such as software programs, instructional materials, music CDs, and even limited-edition art prints. The Creative Works Office, directed by Giovanni Tata (BS and BA ’77), is believed to be the only organization of its kind at any university.

“We help faculty get their creative works seen and used beyond the BYU audience,” says Tata. “Our major mission is to provide a service to faculty.”

The Creative Works Office operates under the same principles as the Technology Transfer Office. Creative Works helps products created on campus find their way into the market and shares in profits with the creators.

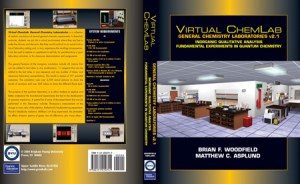

One high-profile product promoted by Creative Works is BYU chemist Brian F. Woodfield’s (BS ’86) Virtual ChemLab. Distributed worldwide, ChemLab is a sophisticated and realistic simulation of instructional chemistry laboratories and covers high school and freshman and sophomore college chemistry. Licensed to Prentice Hall, ChemLab is used by more than 150,000 students.

Another best-selling product is CultureGrams. These reports offer brief descriptions of the daily life and customs of 187 cultures throughout the world. They were first developed in the 1970s by the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies to help students, faculty, and LDS missionaries traveling abroad learn about the cultures they were entering. In the late 1990s CultureGrams was licensed to an outside publisher. CultureGrams has brought more than $340,000 of revenue to the Kennedy Center since it was licensed.

Another best-selling product is CultureGrams. These reports offer brief descriptions of the daily life and customs of 187 cultures throughout the world. They were first developed in the 1970s by the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies to help students, faculty, and LDS missionaries traveling abroad learn about the cultures they were entering. In the late 1990s CultureGrams was licensed to an outside publisher. CultureGrams has brought more than $340,000 of revenue to the Kennedy Center since it was licensed.

Other popular products include OrganTutor and Computer Adapted Placement Exams (CAPE). OrganTutor is a CD-ROM or online course developed by associate music professor R. Don Cook (BM ’80) to teach organ techniques; licensed to Rodgers Instrument Corp. and the Allen Organ Company, it has sold thousands of  copies nationwide. CAPE is a series of online tests to help foreign-language students assess their ability level and select appropriate courses; the tests are used by more than 600 universities in the United States.

copies nationwide. CAPE is a series of online tests to help foreign-language students assess their ability level and select appropriate courses; the tests are used by more than 600 universities in the United States.

When the revenue possibilities for a product are too small to be attractive for licensing to an outside company, the Creative Works Office itself makes the product available through its Web site, creativeworks.byu.edu. There, customers find a variety of products, including documentaries produced by BYU Broadcasting, music CDs featuring BYU faculty and BYU performing groups, a nursing-skills encyclopedia, foreign-language courses, and BYU film classics such as Cipher in the Snow, John Baker’s Last Race, and Johnny Lingo.