3.2 million volumes in the library • 17,000 parking stalls • 439 research laboratories

8:00 AM

IN THE FRENCH HOUSE, they might call it BYU’s raison d’être. English majors might describe it as BYU’s thesis statement. In the Tanner Building it would be BYU’s bottom line. To construction management students, it’s BYU’s foundation.

It’s the magnetic pull that draws some 30,000 students out of bed and onto campus every day. Whatever their academic persuasions, they all enter BYU to learn—to gather facts, bundle skills, winnow assumptions, and harvest the fruits of their mental, physical, and spiritual labors.

By 8 AM on Sept. 22, thousands of students had already begun their educational exertions. They converged on campus in hourly swarms and filtered into about 300 classrooms. Not everyone entered campus solely for a formal education: grounds crew workers planted thousands of pansies, tennis players perfected serves, and students in khaki uniforms issued hundreds of parking tickets. But all these activities helped create an atmosphere for learning.

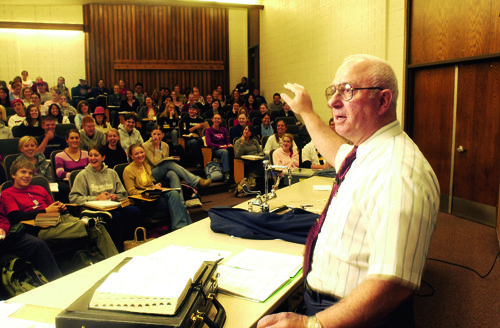

Nowhere was the “enter to learn; go forth to serve” ideology, as BYU’s philosophers might put it, more literally obeyed than in Sharing the Gospel classes, like that taught by associate teaching professor Randy L. Bott (EdD ’88) at 9 AM. There, some 270 students entered to hone the skills that will help them as they go forth to serve on missions and elsewhere. With about 1,100 students crowding his classes each semester, the former mission president has no small influence. “There are missionaries that I’ve taught in every single mission in the world,” Bott claims.

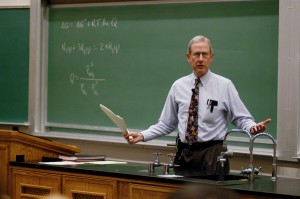

Most classes that students entered, though, provided somewhat more figurative applications of the motto. Among other things, in their classes students studied genetic, geographic, and career mapping; they dissected organisms, sentences, and arguments; they wrote scripts and read scriptures; they considered electrical, social, and oceanic currents; they drew figures, blood, and allusions. And their classrooms were not always indoors: an integrative biology class paraded onto the quad to examine a Douglas fir, and nursing students donned masks and earmuffs and ventured about campus to better understand people with disabilities.

As the tide of classroom learning began to ebb around midday, the number of students in other learning venues swelled. Political science majors packed a lecture on documentary filmmaking abroad; the women’s soccer team honed skills on the field; undergraduates teamed with professors and graduate students in research labs; and students consulted one-on-one with professors in cramped faculty offices.

Cathryn A. Knoles (’06) spent three hours of the 22nd pursuing the melody of her BYU experience, as she might call it, alone in a music practice room deep within the Harris Fine Arts Center. A harpist from Centerville, Utah, Knoles is one of just six BYU harp majors. She has strummed for 15 years and has the calluses to prove it. Despite her love of the harp, she’s glad for a second major in comparative literature, which takes her from the HFAC catacombs to explore other educational realms and ideas.

Encountering and engaging ideas is a fundamental right of every student, a law student might argue. Or, as a physics major might propose, it’s the grand unifying principle that binds BYU students of every academic persuasion.