“I should be dead by now, but here I am,” says Erika Muschik Burton (BA ’20). She adds, “I have a lot of evidence that God has been in my life and rescued me many times.” Burton waded through war, repression, and life as a refugee to realize a dream she’d had since age 4: someday, she had told everyone in her village in Czechoslovakia, she was going to go to America. “They would laugh and tease me. . . . But I thought, ‘I’m going to do it!’”

She did. And last year, in her 80s, this dreamer fulfilled another longtime goal when she officially graduated from BYU. Her degree became a legacy for her posterity—a symbol of what can be accomplished by faith and will.

Burton was 6 years old when Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia and her hometown of Marienbad became part of the Nazi Reich. Even after the Allies liberated Czechoslovakia, Russia’s communist regime was brutal. One night armed Russian soldiers invaded their home and robbed them of their belongings. Erika, her brother, and their mother were all forced into labor at various times. At one point Erika and her brother were taken to work under awful conditions in the fields of a large estate far from their home. She remembers her brother being whipped for taking a bite of an apple from the ground.

When Erika and her brother heard that the Russians were rounding up people and sending them to Siberia, they decided to escape from the estate. Without permits to travel, they left in the middle of the night but were soon captured by Russian soldiers and held in a government building overnight. However, the next day, the head officer gave them an envelope to deliver to a man in a town near their home and provided each of them with travel permits.

“When we got to the town we really tried to find the person,” Burton recalls. “We asked several people but were told that no such street address existed and they had never heard of the name on the envelope. We also discovered that we were now close to home. My brother was so happy that he started to sing out loud. When we got home, Mother cried and laughed. Mom was convinced that the man wanted to help us make it home safely without raising suspicion,” says Burton. “We thanked God for watching over us.”

It wasn’t the last time young Erika saw God’s hand in her life. When she was 12 it was rumored that the government would allow those with proof of German or Austrian descent to leave the country. She was determined to use this opportunity to get her family out, but their faith was tried in the process. Erika managed to secure paperwork that allowed her family to leave the country, but her younger sister was recovering from an emergency appendectomy and scarlet fever in a makeshift hospital in a former hotel. Erika had pushed her sister to the clinic in an abandoned baby carriage, her sister’s legs dangling out the back.

The train to West Germany was scheduled to depart days after the surgery, but Erika knew this was their only chance to leave and begged her mother to go. “I badgered her into it, and she relented,” says Burton.

The family and thousands of others were crammed into cattle cars, 30 people in each, and locked in for the night. “I stood on one leg all night long because all the space had been taken by people sleeping,” Burton remembers. When the train started moving the next day, she didn’t know if they were really going to West Germany or to Siberia, but hours later she was startled by everyone in the cattle cars laughing and cheering. When she saw their yellow identification armbands littering the ground, Erika knew they’d made it into West Germany.

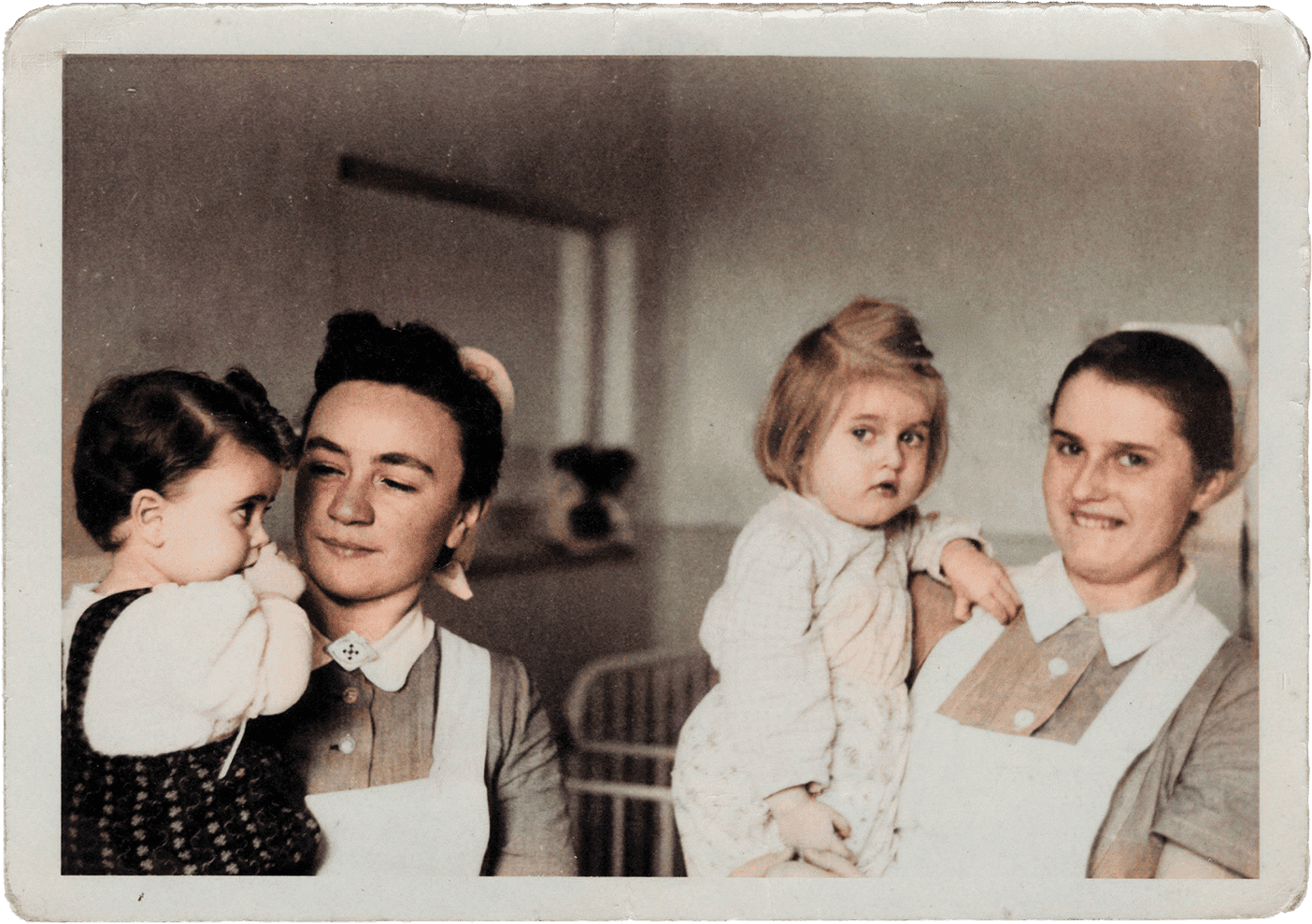

America was a step closer. Erika wanted to become a translator, but college was financially out of reach. She trained to become a nurse instead. Later, she was working as a nurse at the Second General United States Armed Forces Hospital in Landstuhl, Germany, when she met her first husband, an American soldier. They moved to America, settling together in Missouri and later in Illinois.

Three children and many years later, she and her husband ended their marriage. “I had no money, I had no resources, and I didn’t have any family here in America besides my children,” relates Burton. Burton moved to Provo in 1982 and shared a basement apartment with her BYU-student daughter Sonja. “Our little apartment was always full of people who would visit,” says Burton, who joined her daughter in taking classes. When her daughter left to serve a mission, Burton was sure she’d be lonely, but, she says, the students “just kept coming! I was just another student to them.”

“Being a student at BYU brought my mother great joy and restored her hope for the future,” says Sonja Cowgill Jorgenson (BFA ’84). But supporting her children and dealing with health problems kept Burton from finishing her degree. Just a few credits short, she left BYU and married Kay Burton from the Salt Lake City area.

When Sonja recently discovered that her mother had long ago completed related courses while living in Illinois, she petitioned BYU to count these for her remaining credits. Petition granted, Burton graduated last December with a bachelor’s degree in German studies.

“She wanted to finish what she had started for her grandchildren,” says Jorgenson, “to show them that sooner or later, if we persist, we can reach our dreams.”