It’s a tale told in the pages of two Banyans, the onetime BYU yearbook. While the 1916–17 edition is filled with pictures of the Founder’s Day Parade and sporting rivalries (“The ‘Y’ men return the visit of their ‘U’ friends, with disastrous results to the northerners.”), the following school year’s volume is a somber affair, compiled after the United States’ entrance into World War I. The first 28 pages honor the sacrifices during the Great War with poems, war-bond ads, and photo collages of military garrisons. And there are far fewer faces as BYU students answered the call to serve. The 1917 student body boasted 118 male students, while 1918 showed only 52. The Banyan noted the change: “War has ravaged [our] ranks and taken . . . many of its strong college men.”

A hundred years on, BYU is commemorating the service of its alums with a special display in the library and a Nov. 10 conference put on by the Saints at War Project (see saintsatwar.com). Here we remember the service and sacrifice of the Y community during the “war to end all wars.”

In early 1917 the U.S. Army had only 133,000 soldiers, but a draft and floods of volunteers increased that number to 4.8 million who served in World War I. A 22-year-old Spencer W. Kimball was one BYU draftee, writing to BYU leadership on Sept. 26, 1917, that his “abrupt discontinuance” from school was due to his “authoritative call to arms.” About 160 students and a handful of faculty members would serve.

“War has ravaged [our] ranks and taken . . . many of its strong college men.” —Banyan, 1918 edition

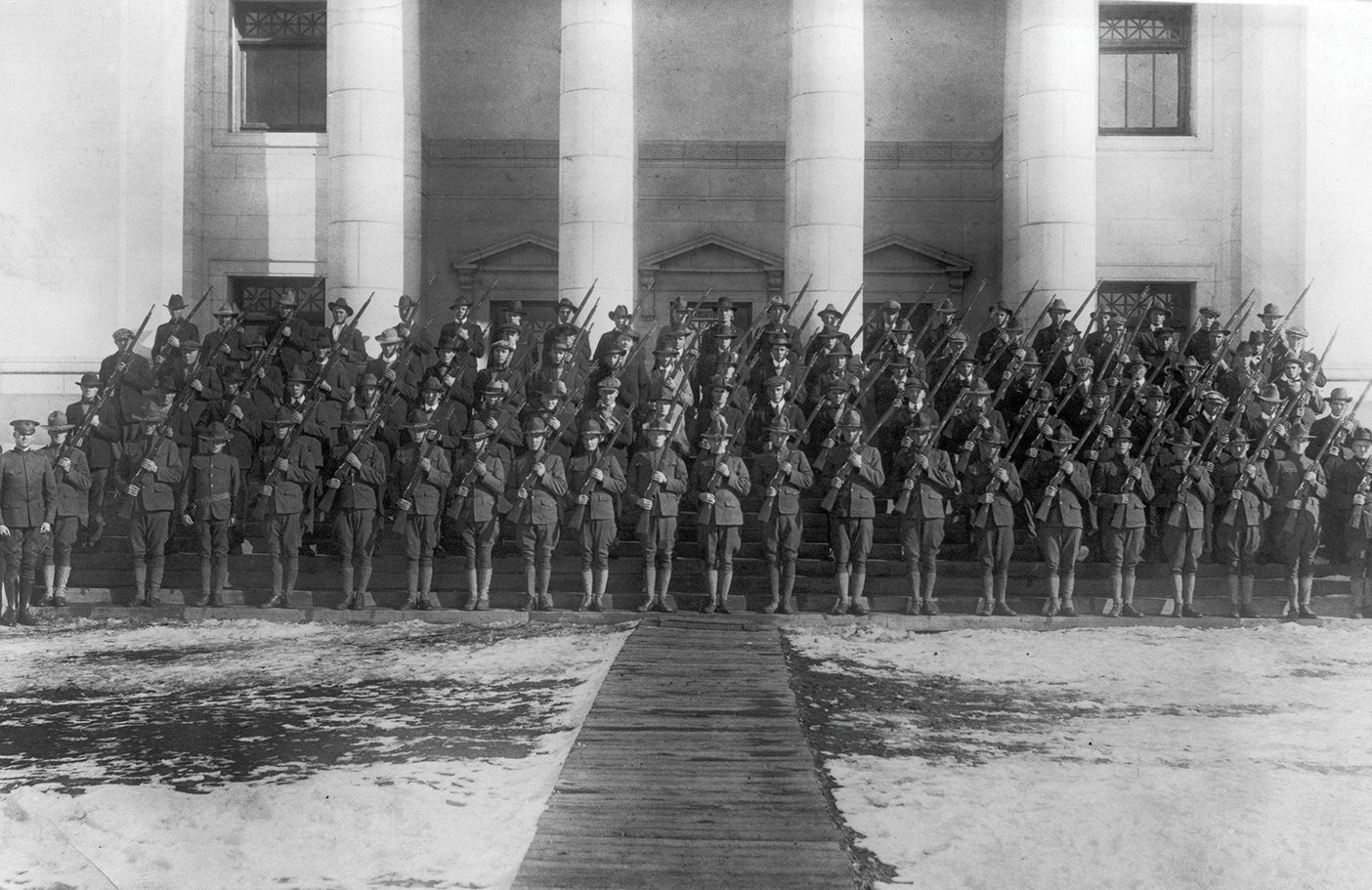

Campus itself also helped the cause. In September 1918 a Student Army Training Corps unit was established at BYU, and the Maeser Memorial Building was transformed into military housing. Students rallied behind the motto of “to the front or to the farm,” providing goods to the troops. The Women’s Club raised $300 (worth around $5,000 today) for the Red Cross and the Belgian Relief Fund.

A knitting frenzy swept across campus: “Yarn—more yarn—needles and more yarn. ‘Knit your bit,’” proclaims a Banyan calendar item. BYU students knitted 174 sweaters, 50 pairs of socks, 25 shawls, and 19 scarves.

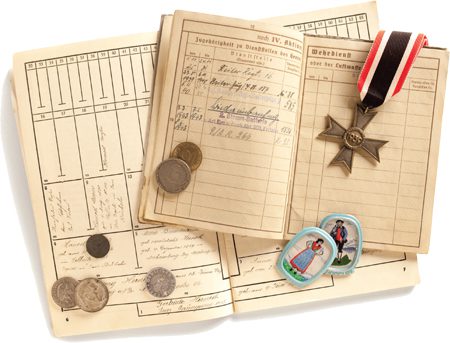

Service groups sent care packages to BYU students-turned-soldiers such as Nels Anderson (AB 1920), who religiously kept a journal during the war: “Time is still dragging and so is the war,” Anderson wrote while serving on the French front. “I wish I could write down just how it feels to be under fire for four or five hours.”

Fifteen BYU students perished in the war—from combat and from the Spanish influenza, which also hit Provo and closed down BYU for several weeks. On Nov. 11, 1918, when the armistice was signed and the war ended, all rejoiced—including Anderson: “So this is peace and I am alive. I am so surprised. I don’t know how to act so I just sit and think. . . . How good it is to be alive.”