For four decades Clayton White has oft taken to the wing in a quest to understand peregrine falcons and mentor fledgling scientists.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

For a wingless creature, Clayton M. White has spent a surprising amount of time in the sky, dangling over cliff faces and otherwise catching air in his passionate pursuit of eagles, hawks, and falcons. The wandering zoology professor often uses helicopters, ultralights, or seaplanes to reach his subjects, and he’s not one to complain about the need to occasionally rappel down a rocky crag to peer into a nest.

White admits that he has a recurring dream about flight, a worrisome episode in which he can only move slowly, unable to make it to the plane. But with an early start, today he is airborne, sitting comfortably inside a shiny 737 that hugs the coast of North America en route from Seattle to Fairbanks, in central Alaska.

He first visited Alaska as a graduate student 40 years ago, in the years before a vast pipeline cut across the wilderness, a time when the future of many birds of prey looked bleak. During this critical juncture, when several species were facing extinction, White followed the flight path of the peregrine falcon. He took hops to Alaska and leaps to Australia, Fiji, Vanuatu, Argentina, and Brazil, all to study the dwindling populations and make recommendations on how to save them.

The name peregrine is derived from the Latin peregrinus, meaning wanderer. The name fits both the migratory bird and the nomadic professor who has visited 58 countries. His recurring trips to Alaska also earned him the name “Birdman of Umiat” after a remote airfield on the North Slope that became a frequent starting point for raptor research.

Four decades of study have made White a recognized expert on raptors, and he is often asked to consult on projects for U.S. government agencies and commercial industries. The latest invitation, from friends at the U.S. Forest Service, is an opportunity to share his expertise and enthusiasm with staffers of Alaska Senator Ted Stevens.

“One of the most important things you can do is to get a politician out where he can have a hands-on experience in the wild,” says White. The group will spend the day on the Tanana River, searching for fledgling falcons and listening to White talk about the bird’s journey back from the brink of extinction.

Out in the Middle of Nowhere

From the plane’s oval window, White sees the familiar arctic terrain draw closer. Ragged green-brown islands are rimmed with white chunks of glacier that have traveled the muted blue sea and stranded themselves in the shallows. As the coast becomes land, granite peaks and deep valleys, carved by ice and time, emerge through the gray smoke of a nearby forest fire.

On the ground, White makes his way through the streets of Fairbanks. The day is hazy but mild as he heads to a riverside restaurant near the airport to talk over details of the next day’s trip with former grad student Douglas A. “Sandy” Boyce (PhD ’89) and his boss, Thomas M. Quigley.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

Boyce, who now heads a Forest Service research lab in Juneau, asks about BYU football and the underground library addition and then starts to rib White, who is seated across from him at a table on the restaurant’s wooden deck.

“Clayton’s office has deep stacks of papers,” says Boyce, explaining White’s filing system. “I’d go in and ask him for a reprint of an article and he would thumb about a quarter of the way down, remove a stack, and pull out the paper. Once, to test my theory that he knew where everything was, I moved an old piece of steel to the left about a foot and put a piece of paper over it. He noticed something was out of place almost immediately.”

White explains, “I have 7,300 reprints, and they are all filed except this one stack. I’ve been in the same office since Sept. 5, 1970, and I’ve accumulated a lot of stuff.”

White has published over 160 articles and coauthored dozens of book chapters. Currently he is coauthor with Tom Cade of Peregrine Falcons of the World, an illustrated book by Cornell University Press. To honor his academic achievements, BYU gave him the Karl G. Maeser Research Award in 1996.

Boyce has shared many adventures, from Argentina to Alaska, with his former professor. He first met White in 1977 when they went looking for gyrfalcons, peregrine falcons, and rough-legged hawks.

“We went up to Umiat, in the far-northern part of Alaska, where it’s all tundra. It’s just this outpost in the middle of nowhere with a gravel runway,” he recalls. “After we land there, we jump into this helicopter and start flying along the river. And below we start seeing all these grizzly bears along the river.

“After we land Clayton turns to me and says, ‘I want you to go that way,’ but he and the rest of the group go the other way. And I think, ‘Okay, no problem. I’ll just do what he says.’ Soon I’m hiking along through 8- and 9-foot willows and it dawns on me that we’ve just flown over about 10 grizzly bears and he told me to head off that way by myself!”

White interjects, “I had to break him in properly. If you don’t keep them off balance, they get too confident.”

Boyce was the unknowing beneficiary of an ornithologist tradition—fledgling students are urged out to the edge of the cliff to test their wings. White explains that his own mentor, Tom Cade, then a professor at Cornell University, also liked to throw students into research.

“In 1965 Cade asked me to go up and run a project in Alaska on the Yukon River—to collect some falcons and establish baselines for pesticides,” says White. “I was thrown into research and he trusted I could do the work. The fact that he had the confidence I could do it was very good for me.” White has since mentored scores of students—like Boyce—the same way.

Boyce recounts another trip, another flight “way out in the middle of nowhere,” followed by a six-day trip down a shallow river.

“We go down this river against the wind and I see that in the first six hours we’ve used about half to three-quarters of the fuel.” After the first day Boyce decides that to ration fuel they’ll pull the boat; but White hadn’t brought hip boots.

“We went for days while I pulled this boat,” says Boyce. “I’d look behind me and he’d be sitting on the boat and I’d be pulling him down river, thinking, ‘I guess it makes sense; he doesn’t have any hip boots.’”

“There are only two ways to solve that problem,” laughs Clayton. “You can either sit in the boat or you can say, ‘May I borrow your boots?’ But the second option would deprive him of the learning experience.”

The stories and laughter linger into the cool evening. After the meal they discuss the next day’s tour and where they will meet Jim Egan and Diane Hutchinson, staff assistants from Stevens’ regional offices.

“What we want to do is build relationships,” says Quigley. “Having a relationship with them can make a big difference. They are willing to listen and understand the issues and not just go by the rumors.”

After looking at a map with likely falcon eyries circled, the researchers are hopeful. “The timing should be perfect for when the birds are fledging or just fledged,” says Boyce. “But let’s cross our fingers.”

Down on the River

The next morning, the smoky skies begin to clear, appearing a shade lighter than the murky channels of the Tanana River. The group—now with Egan and Hutchinson—boards a lightweight aluminum boat (with plenty of fuel) for a trip down the silty, timber-infested river, where they hope to see Falco peregrinus anatum, the dark-plumaged cousin to the falcon subspecies Falco peregrinus tundrius, which White named back in 1968.

Each year the dynamic Tanana River meanders and splits as it freezes and thaws, creating a turf war between water and land. In the spring the thick ice breaks into chunks that shred and tear at the bank, dislodging both soil and plants. Damaged trees lean dangerously outward and branches and logs float by in the liquid periphery.

Dodging sandbars and floating logs, the guide moves the group down the river for about four miles and then, with a cue from Boyce, idles the craft on a smooth stretch of river bordered by a 90-foot cliff.

“Peregrines are attracted to the cliff,” White says. “That’s called philopatry, the love of one’s home. It brings the falcons back to the same cliff year after year.”

An unimpressive narrow ledge, about 30 feet above the water, is all that marks the falcon eyrie. The nest itself—nothing more than a shallow scrape in the rock surface, just enough to keep an egg from rolling—would be invisible if it weren’t for a single surviving falcon chick. With black wings, buff-colored breast, and fluffy white down on its legs, the fledgling is eating lunch—a green-winged teal—recently delivered by its parents. “This is perfect,” White says. “Peregrines were called duck hawks until about 1950. There’s a classic painting from the early 1800s by John James Audubon that shows two young ones feeding on a duck just like that one.”

As the observers watch from the boat below, the bird eats its fill and then totters awkwardly around the nest with the stiff-legged movements of a creature built to fly, not walk.

For White, who worked on the Tanana River in the 1960s when the birds had all but disappeared here, seeing the young peregrine is a thrill and his voice is enthusiastic as he explains its significance to his appreciative tour group.

For the two political advisors, this exposure to Alaska’s wildlife will enrich their perspectives and inform their opinions. Across the continent, in his

Washington, D.C., office, their boss grapples with sensitive issues, as oil interests and environmental groups lobby hard for their respective positions.

Hutchinson and Egan ask about falcon eggs, flight, and life span. White’s replies are full of details. “Eggs are about the size of a large chicken egg. But these are a spectacular color—a beautiful reddish chestnut, a cinnamon red, with black spots on them—really pretty.”

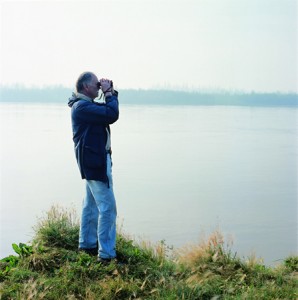

White looks at the nest with his binoculars. “When they are born, they are all white with fluffy down. They can fly with that on there but normally don’t until black feathers have replaced most of the down.”

A moment later, Egan points to a tall tree at the top right of the cliff and says, “When you get a chance, check out the female. She’s cleaning herself.”

White trains his binoculars on the tree. “She’s just not one bit concerned, is she?”

From her perch on a bare snag, the young falcon’s mother watches over the river and the nest, occasionally preening and stretching.

“Her life span is probably 10 to 12 years,” White says. “The longest we know of is about 18 years in the wild. And longevity depends in part on how many young she raises.”

Then all eyes turn to the sky as a slightly smaller falcon, the adult male, soars in from the horizon. He swoops, screaming in alarm, then speeds upward, talons trailing. His long elliptical passes are dizzying above the boat.

White observes aloud, “When they reach about 200 miles an hour in a dive, they change their configuration by pulling a wing up and becoming asymmetrical, allowing them to go even faster. It is called hyperstreamlining. The maximum speed recorded in a dive is 242.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

“If we can get them both in the air, you’ll see that she’s got a much longer tail proportionally than he does and a much lower call. You’ll hear him going ‘cack, cack, cack, cack,’ and she’ll be going ‘cyack, cyack, cyack, cyack.’”

As the male adult continues his surveillance overhead, White pauses a moment to write in his yellow waterproof field notebook. This trip may be more about making friends than gathering scientific data, but the observations are still noteworthy to a researcher who has devoted his life to studying these magnificent birds.

After studying redpoll finches and working on a master’s degree from the University of Alaska in 1963, White conducted high-profile research on wildlife for government agencies and oil industries. He recommended realignment of sections of the Alaskan Pipeline to protect falcons, measured the effects of underground nuclear testing on birds in the Aleutian Islands, and studied the Exxon Valdez disaster’s impact on bald eagles in Prince William Sound.

White became an eyewitness to the peregrine falcon’s hopeful history, watching as falcon populations—which had dropped to just 39 nesting pairs in the western U.S.—began to rebound after the government banned the agricultural pesticide DDT in 1972. Adult birds could endure exposure to DDT, but the chemical made their eggshells too thin to survive.

“I just happened to be studying them at the time so I was kind of at the crest of the wave,” he says. “The solution, very simply, was to ban the chemicals. Now these birds are back in great numbers. They are coming back in higher numbers than we ever thought possible.”

A moment passes with just the river and the cliff and the birds painted against the sky, quiet but for the gurgle of the engine and the light splash of water lapping against the sides of the boat. Unable to contain the perfect moment any longer, White claps his hands and offers an enthusiastic “All right!” His joyful outburst is loud enough that both humans and falcons pause for a moment. “Now, Clayton, don’t get so excited. It’s just a bird,” says Boyce.

White responds with a thoughtful smile: “Yes. But it has godlike characteristics.”

Boyce later says, “He’s been studying the peregrine for almost five decades. When you understand something that deeply, you have a sense of awe about it. You can see why Clayton would have a great deal of respect for a bird like that.”

On their visit to the falcons on the Tanana, Egan and Hutchinson have seen firsthand how informed policy making in Washington, such as the decision to ban DDT, can affect wildlife populations. Such informed politicians will be important in the environmental challenges ahead, says Boyce.

The Pipeline and Preserving Alaska

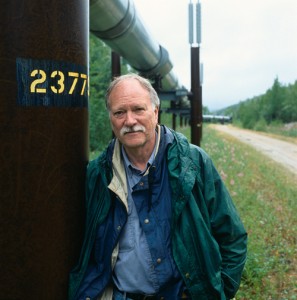

The sun never sinks below the horizon during the Alaskan summer night, and the new day arrives without the fanfare of dawn. The relationship-building expedition over, today White will make a quick tourist stop at the Alaska Pipeline, which winds for 800 miles over mountain ranges and rivers, from the oil-producing fields of the North Slope to Prince William Sound on the southern coast.

On a drive north to the pipeline on the corrugated, weather-warped Steese Highway, White explains his role in its construction. In 1975, he worked for the Department of Energy, researching the proposed pipeline route. “My job was mainly to find out where peregrine falcons and other birds might be nesting relative to the pipeline, make some predictions, and recommend how to lessen its impact on wildlife.”

Once he reaches the pipeline, White parks on a gravel maintenance road and surveys the line for a moment, his boots crunching in the gravel as he strides past the massive man-made phenomenon. Light rain drips down the sides of the 48-inch-diameter carbon steel pipe; vibrant scarlet blooms of Alaskan fireweed reach up on tall stems from a green carpet of moss and lichen-covered soil.

Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

“Many of the dire predictions have turned out not to be true. One was that caribou would see the pipeline and be afraid of it,” says White, noting that the line was elevated to allow for migration of Alaska’s large caribou herds. “The fact is that they often don’t use the special crossways built for them, and they just go under the line instead. They stand there for the shade, too.”

Through his experiences, White has gained a practical, balanced vision of the environment, but that doesn’t mean he favors industry at any cost. When the latest budget resolution included a provision that would allow oil drilling in the Alaska National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), he shared his frustration in a Daily Universearticle. “Congress didn’t vote on ANWR, they voted on a budget. There is 73 percent of the Northern Slope that is already available for drilling. My question is, ‘Why do they have to go into the other 27 percent?’”

Later, in a guest column in the Daily Herald, White explained that the United States has but one chance remaining to keep, for who knows how many generations, the country’s remaining intact block of Arctic habitat. “The question really is not one of birds, caribou, or other animals,” he wrote, “but rather the inheritance that we leave others in a busy world, an inheritance that will have increasing value in the long term.”

“Because of all his travels and his strong bonds with people in other countries, Clayton is concerned for the world at large,” says his wife, Merle, who works as an advisor in BYU’s College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences. “I think that’s part of the reason he has such strong feelings about the drilling in Alaska. It’s an educated vision of what’s happening from someone who has worked in Alaska, has studied the habitats, studied the wildlife, but it’s also personal.”

From the pipeline, White heads south, back through Fairbanks and past North Pole, Alaska. This trip to Alaska is quickly drawing to a close but White has learned of another active falcon eyrie right by the Richardson Highway. As he nears the designated mile marker, an F-16 Viper from nearby Eielson Air Force Base can be seen cruising just above the horizon.

Unlike the Tanana River eyrie, this nesting site is on a small cliff just 100 yards off the busy road. Through his binoculars White spots three young falcons, two dark ones and one that is almost completely down-covered. The birds seem unruffled by the noise of the nearby traffic.

“When those young grow up,” White says, “they’ll come back and find yet a punier cliff because all the big cliffs will be occupied. This is unbelievable. I could almost walk into that nest site, but I would get soaking wet because of the rain on that thick brush.”

Unable to resist, White crosses the road and disappears into the trees. Moments later the female falcon flies from her bare snag. The male soon joins in the aerial display, and they both swoop and scream overhead. White carefully works his way in to get a closer view of the eyrie and contemplate the future of the three young falcons.

In a few short months, this family of birds living in arctic Alaska will migrate over 7,000 miles, perhaps as far as Argentina, before the cold winter. Next spring they will return to compete for the same narrow cliffs, then breed and raise young. Chances are Clayton White will find a reason to fly in and see how they are doing.

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

The Fall and Rise of the Peregrine

Photo by Dan Brimm

Clayton White had just captured a young peregrine from its eyrie 60 feet down a cliff on tropical Wakaya Island, Fiji, in 1986. “Just as I prepared to ascend I slipped on a rock and with full body weight my knee hit the rough volcanic face. The pain was excruciating,” he writes in his new book,Peregrine Quest: From a Naturalist’s Field Notebooks. Two hardy Fijians hauled him up hand over hand to the top. The young falcon (pictured below) was later taken to a captive breeding facility.

In the early 1970s White also took a young peregrine from Peregrine Point in the Aleutian Islands as part of a program to reintroduce falcons into the eastern United States.

Although North American falcon populations have staged a remarkable comeback in the last 30 years, falcon populations in Fiji continue to decline. There, at the extreme end of the falcon’s range, White and colleague Daniel Brimm are leading a research and recovery effort.

“Where we started with 15 eyries 20 years ago, we now have only two or three left. Something’s happened and we’re not quite sure what it is. We don’t understand tropical bird biology well, but it may simply be a cyclic phenomenon.”

White’s DNA studies of the falcon population reveal that it is highly inbred, that there wasn’t “one cent’s worth of difference” in the DNA of birds from four separate Fijian islands. Because of the difficulties and expense of a thorough study, the researchers have been unable to determine whether the declines are due to inbreeding, male infertility, or even hunting. Whatever the cause, White and Brimm have introduced genetic material from Australia into the population to breed falcons for release in Fiji.

While they have had very limited success, many Fijians are grateful for their efforts; a plaque on the captive breeding facility in Kula EcoPark dedicated to White and Brimm thanks them “for more than 15 years of research they have devoted to the Fiji Peregrine Falcon.”

Ghosts of the Prairie

Each spring since 1995 White has sent two students– like Jeremy B. Hutson (’06) and Katie Gibbon Hutson (’05)– to Utah’s high desert to search for elusive mountain plovers. Photo by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94).

On the high desert plain of Eight Mile Flat near Castle Peak, Utah, oil wells dot the landscape where years ago a handful of mountain plovers nested. The birds have not flown in from California to nest here, perhaps continuing on to Montana or Colorado. White and his students are still hopeful that the birds will return.

Since 1995 two BYU students have ventured out each spring to look for mountain plovers—a shorebird that lives in the short grass near prairie dog colonies—or, in their absence, to study whether conditions in the area would sustain the elusive birds should they return.

“Because these birds once qualified as a candidate or threatened species, the Bureau of Land Management wanted to know if oil production bothered the plovers,” says White.

“The most we ever found were four nests, and they were hard to find. When they are in low numbers, they’re even harder to find. The plover is such a secretive bird, sometimes called the ‘ghost of the prairie.’ You’ll be looking at one of them and blink, and it practically disappears right before your eyes.”

White doesn’t think that oil production displaced the missing plovers, suggesting instead that years of drought or other factors might have led to their decline.

For White and his students, this section of the Uinta Basin has become a proving ground, where biology students decide whether or not they want to be scientists.

“I ask in class for two students to come and do some really boring work in the summer,” White says. “I explain to them how boring it gets, how hot it gets, and try to discourage them—and those who persist are people who want to do biology.”

Four times each month in the spring of 2004, undergraduate married couple Jeremy B. Hutson (’06) and Katie Gibbon Hutson (’05) contacted White to report on insects, birds, prairie dog pups, pronghorn calves, and vegetation at the site.

“He keeps us excited about the work because he always has so much enthusiasm in his voice. It just makes work more enjoyable,” Jeremy says. “The average person after two weeks of this would probably get really discouraged and frustrated, but Dr. White doesn’t just want to know about plovers. He wants to know if we’ve seen golden eagle chicks or a peregrine nest—or he tells us to go check out a different location.”

“He’s probably heard the same information year after year,” says Katie, “but he still sounds excited.”

If the ghosts of the prairie don’t return to their old haunt, White has an alternative. “I guess we can always take a trip over to the Pawnee grasslands in Colorado and see some plovers,” he says with a wink. His lack of concern reveals that his work here is not counting plovers, but helping students earn their scientific wings.

The Love of One’s Home

After flying south for the winter, anywhere from Texas to Argentina, peregrine falcons return to the same Alaskan cliffs to breed and raise their young. According to scientific summaries written by Clayton White and his colleagues, these swift raptors are “one of the most widely distributed of warm-blooded terrestrial vertebrates.” Only humans inhabit more areas of the Earth.

White explains that falcons, like humans, will leave home but often return when it comes time to raise a family. “Peregrines are attracted to the cliff. That’s what we call philopatry, the love of one’s home. That brings the falcons back to the same cliff year after year.”

As it turns out, every two years the White family would return to Utah after moving, for school or work, to a different state—first Alaska, then Kansas, New York, and Maryland. “It felt like we were always moving. I think that it was consistently every two years,” says White’s wife, Merle.

As Clayton walks across the thick, green lawn in front of his modest Orem home, Merle gives a wry smile when asked what Clayton likes to do in his spare time. “He likes to mow the lawn,” she says. “He mows it twice a week because I fertilize it. He gripes about it every time, and he hides the fertilizer from me occasionally so that I won’t. Look how green it is.”

Through a long hallway filled with primitive masks from his travels, Clayton carries bags of groceries to the kitchen, where he will prepare a spaghetti dinner. When he finds some extra time, he says, he would like to attend chef school. “I really like fine cuisine. I really do. Probably 50 percent of cooking is the spices you use.”

“Clayton does most of the cooking and does all of the grocery shopping. I have to ask him if something’s a good price,” Merle says. “He makes pancakes for the grandkids and they love that.

“Every year Clayton dries the golden delicious apples from our tree and makes apple chips that are just perfect. We have people who line up for Clayton’s apple chips.”

Merle works on campus as an advisor in the College of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, and she and Clayton chat about the events of their BYU workdays. Then their discussion turns to retirement as Clayton has recently turned 69.

“I’m going to work at least two more years. Either you have a job or a profession. For me, it’s a profession. Actors, senators, the Pope—they don’t retire at 65. There is a litany of successful people who enjoy their professions, and they don’t want to quit and come home and sit in a chair and read books. I kind of have adopted that philosophy. I really like what I do.”

Merle makes the lighthearted suggestion that Clayton could put his international experience to use directing traffic. “I know, you want to go direct traffic down at the roundabout by UVSC.”

“Some people just don’t know how to drive the roundabouts and I think I could help.” Clayton says with a smile.

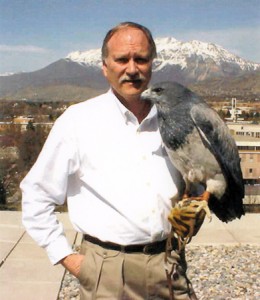

White says one of his joys is spending time with his wife, children, and grandchildren. Merle produces a picture of Clayton with a majestic grey bird perched on his fist.

“Here is a family member who died last year,” she says of the bird. “We called him Picchu, and he’s gone to every grade school that our grandchildren have ever attended. That has been a real bonding experience—taking creatures to school and talking about our relationship to nature.”

White’s family shares his adventurous spirit and love of world travel. He and Merle stood at the mouth of a volcano in Vanuatu. With his grandsons, he recently floated on a Brazilian riverboat from which they saw pink dolphins and caimans and swam in the confluence of the Rio Negro and the Amazon. This trip was part of a White family travel tradition that began when their children finished high school. “We take our kids somewhere around the world so they will have an experience outside the country, to see other things. We’re doing it now with our grandkids when they turn 15. I wouldn’t give up that experience for anything,” Clayton says.

Before driving home, White gave a final exam to the small group of grad students from his Birds of the World class. The class was held downstairs in the Monte L. Bean Museum, in a room with row upon row of metal drawers. White is curator of the museum’s bird collection which houses about 9,800 scientific specimens and 5,000 eggshells, representing about 98 percent of the world’s bird families.

One of the students’ assignments last semester was to get up in front of the class and share research gathered about different bird species. After a short report on dippers, a darting songbird that often builds its home near creeks or alpine waterfalls, White reveals that, if he could be any bird, he would be a dipper.

“Have you ever thought about a dipper, a water ouzel?,” he says. “It’s a dark gray bird and when it blinks, its eyelids are white. It has very few predators. It enjoys a nice cozy nest where it can listen to the water. It’s a great life.”

The globetrotting professor who has spent decades following falcons and other wandering birds of prey now seems content with a more tranquil life closer to home.