Banishing Poverty to Museums and History Books

Banishing Poverty to Museums and History Books

By Lisa Ann Jackson Thomson in the Spring 1999 Issue

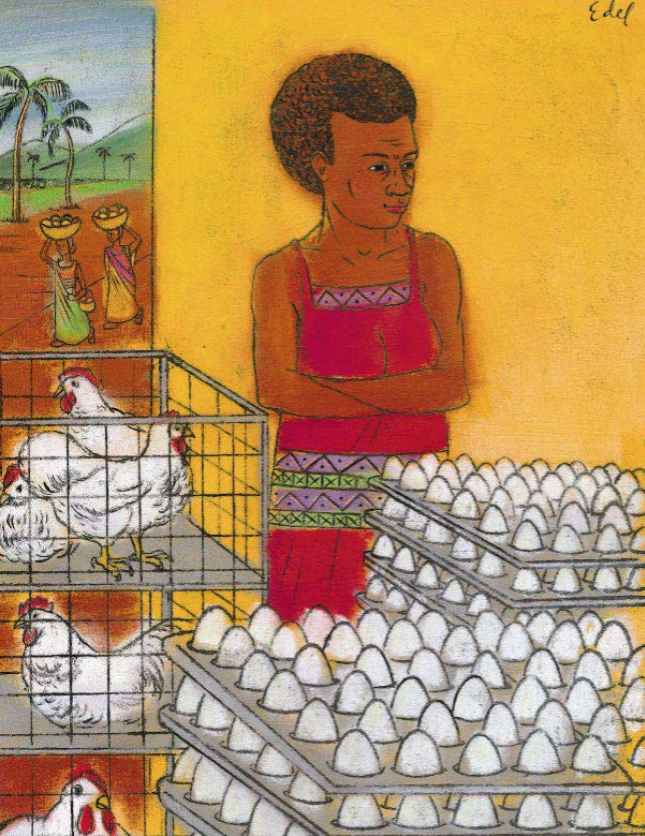

Illustrations by Edel Rodriguez

For Vincent Musaalo, the spectacle of children starving and naked in famine-ravaged Africa was not a PBS documentary or the cover of National Geographic. It was life. Vincent grew up in he kind of poverty most of his fellow BYU students will never know. For him and his family, obtaining life-sustaining food was the primary chore each day. Some days they didn’t accomplish their task.

Vincent is from Uganda and grew up during the drought that crippled much of Africa in the 1980s. He saw malnourished children with bloated bellies devour what should have been life-saving cereal and then die because their weakened systems could no loner digest it. The common cold and seasonal flu became deadly diseases in nutrient-deficient bodies. For many there was no electricity, no indoor plumbing, no running water. The realities of basic survival confronted Ugandans daily.

Vincent, however, was fortunate. He excelled in school and earned a scholarship that took him from the hardships of Uganda to vocational training in Italy. There he met a student from Bolivia who introduced him to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Vincent joined the Church and served a mission in Italy. During his mission he learned from American companions about a Church-sponsored university in the United States, and he was later offered private funding to attend BYU.

Arriving in Provo in 1991, Vincent took a custodial job, working early mornings or late nights while he earned a bachelor’s degree in international relations. But his family in Uganda was never far from his thoughts. His mother wrote often, telling him of their suffering and asking for help. Vincent saved what he could from his student wages and sent funds to his family as often as he could. But it was never sufficient.

Vincent had heard of a Christian missionary from Germany who was helping people raise layer hens in his hometown. He decided to save enough money to purchase chicks for his mother so she could start a small egg-selling business. When he had saved $400 he purchased 200 chicks. His mother successfully raised her first round of chicks and was able to sell the eggs they produced. From her earnings, she fed her family and later expanded her small business. Today her farm consists of 500 layer and broiler chickens, and she has become a supplier for local schools, restaurants, and hotels.

“This is the biggest thing I have ever done,” says Vincent, now a second-year MBA student at BYU. “Some people around me think I’m crazy and laugh about my chickens, but you have to come from the background that I come from to understand what a big deal this is.”

Vincent is convinced that a small amount of money can be a big deal. He is among a growing number worldwide who say access to credit can dramatically change the face of poverty by providing opportunities for the impoverished to earn their way to self-sufficiency.

The notion is called microcredit, and it’s turning traditional third-world development on its head, says Ned C. Hill, dean of BYU’s Marriott School. It began as an experiment in a Bangladeshi village in the mid-1970s. As the experiment has proven itself again and again, the movement has gained momentum, promising to be a leading economic development strategy in the new millennium.

With the stated goals of teaching self-reliance and building self-worth, the microcredit movement has gained strong support from the BYU community. Through providing lectures, hosting conferences, sponsoring interns, and creating microcredit projects, BYU hovers at the forefront of educational institutions championing the microcredit cause. In the process, students and professors in Provo are helping shape a worldwide movement, the ultimate goal of which, according to Muhammad Yunus, the movement’s founder, is to “banish poverty to museum displays and history books.”

Microcredit proponents often cite the old adage, “Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day; teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime.” But they add that the man already knows how to fish–he’s just doing it by hand. Lend him enough to buy a net and you feed a village.

“Some people around me think I’m crazy and laugh about my chickens, but you have to come from the background that I come from to understand what a big deal this is.” —Vincent Musaalo

That’s the microcredit model: provide loans–tiny loans, amounts a bank would scoff at lending–to impoverished people and allow them to earn their way out of poverty by creating and running small-scale businesses.

“We are not talking about businesses that are ever going to be Fortune 500 companies,” says Gary M. Woller, a BYU associate professor of public management. “We’re talking about very small-scale businesses that earn very small incomes, but which enable families to feed themselves and meet their basic needs.”

A typical loan is enough to buy a fishing net or some bamboo or a sewing machine. The average loan given by Grameen Bank in Bangladesh, the largest microlending organization, is $180.

When naysayers claim the poor lack the skills to be successful, proponents remind them that these people have survived under the harshest of circumstances. They have ability; what they need is opportunity, says Woller, who will be spending the 1999–2000 school year on sabbatical, researching and developing microcredit strategies with the Foundation for International Community Assistance (FINCA), a leading microcredit organization.

“The fact that the poor survive is amazing,” he says. “They have acquired tremendous survival skills over the years. Part of those survival skills is the scramble to find ways to make a buck. What microcredit does is provide what they lack–capital.”

“We’ve tended to think of the poor as lazy or incapable,” says Geoff Davis, a program officer for Grameen Foundation USA and a 1995 BYU graduate. “But they’re no different from you or me except we have more money. They are quite capable of working their own way out of poverty given the chance.”

Take, for instance, a couple that Stephen W. Gibson met in the Philippines. Gibson is the Marriott School’s entrepreneur in residence and a member of BYU’s Committee to Alleviate Family Poverty Through Microcredit. Through his work with Enterprise Mentors, a development organization co-founded by BYU professor Warner P. Woodworth, Gibson met Myrna Ramos and her husband, who make cleaning rags to sell at the market. They would crouch on the cement floor of their two-room shanty, taking turns cutting fabric with a dull pair of scissors. Then, because they couldn’t pay for electricity to power their sewing machine, the woman hand-sewed layers together to make durable cloths.

Although the family could sell all the rags they made, their insufficient supplies and equipment limited their productivity. But with a microloan from Enterprise Mentors–about $30–the couple replaced their worn scissors with two new pairs. The added equipment allowed them to produce more rags and increase their earnings. They have repaid their loan and are now working toward a second loan to pay for electricity. Most important, they are better able to meet the basic needs of their family.

Traditional, large-scale development efforts have not fully met people’s basic needs, such as food and shelter, says Woller. Governments and organizations continually pour billions of dollars into roads, airports, and education systems for third-world countries. But it often takes years for the effects to trickle down to impoverished individuals. In the meantime worldwide poverty numbers continue to be staggering. According to 1997 figures, more than a billion people earn less than $1 a day.

“We need to work at the micro level and see to immediate needs,” Woller says. “If we wait for governments to enact the right macroeconomic policy, we could be waiting for decades.”

While microcredit proponents don’t presume to replace macro development, they do hope to address the grassroots niche not being filled by traditional development efforts or even by charities, says Woodworth, a professor of organizational leadership and strategy and the father of microcredit efforts at BYU. Microcredit fills that niche by providing a way for the poor to help themselves out of poverty, merging principles of self-reliance and loving thy neighbor.

“No one has the power to completely change the world, but we do have the power, and hopefully the motivation, to improve a small slice of it.” —Gary Woller

“The notion of microcredit combines the best ideas from all across the spectrum,” says Donald L. Adolphson, associate director of BYU’s Romney Institute of Public Management and a member of the Committee to Alleviate Family Poverty Through Microcredit. “It combines a passion for social justice and caring for the poor with an understanding of how effectively free markets work.”

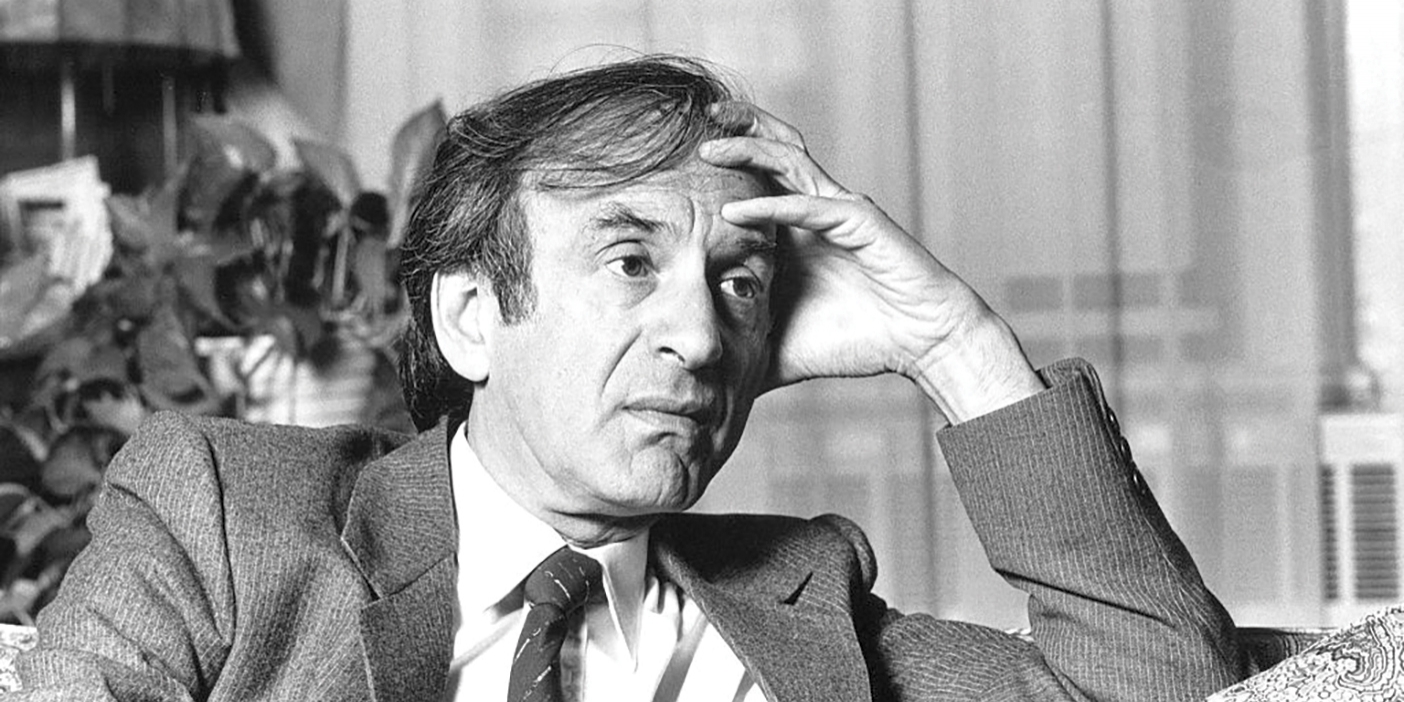

This courtship between capitalism and socialism began 27 years ago in Bangladesh under the hand of Muhammad Yunus, who was awarded an honorary doctorate of humane letters at BYU’s August 1998 commencement. In 1971, with a PhD in economics from Vanderbilt University, Yunus returned to his home in Bangladesh. His country was only weeks old, having just emerged from a civil war in Pakistan. After a nine-month fight for independence, a country the size of Utah with a population half that of the United States was left in economic ruin. Yunus, an economics professor at Chittagong University, was deeply disturbed by the problems facing his country.

“I was teaching on a beautiful campus–teaching grand, beautiful, elegant theories of economics–and outside the classroom in the village I saw people about to die because they did not have enough to eat,” Yunus told an audience at BYU’s Marriott School during his August visit. “I soon realized that there was a great distance between the real life of the poor and the hungry people and the make-believe world of economic theory.”

In his efforts to bridge the gap between theory and real life, Yunus came across a woman who made bamboo stools for a living. He discovered that her small business earned only two pennies a day. She was forced to borrow money from a trader to buy the bamboo and was required to sell the stool back to him at his price.

Yunus asked her how much she would need to purchase the bamboo for herself rather than going through the trader. Her answer: 25 cents. Her situation was not unique. He met 42 people and found that a combined total of $27 was all they needed to bypass greedy middlemen.

Yunus decided to offer them loans to replace the traders’ credits. When he found that these people repaid the loans and, more important, were genuinely grateful for being treated fairly, he approached a local bank about making loans available for others. He was flatly denied and was told, “Poor people are not credit worthy.” He set out to disprove the banker and co-signed on loans in his village. When each individual had paid in full, the banker was still skeptical. Working next in two villages and then in five and 10 and 50, Yunus showed that no matter how many villages and how many loans, poor people are credit worthy and can earn money.

The banker remained unconvinced. So Yunus decided to create his own bank, and in 1983 the first branch of Grameen Bank opened. Today Grameen (a Bengali word meaning “village”) Bank operates in 39,000 villages in Bangladesh, loaning $2.4 billion to 2.3 million borrowers, 94 percent of whom are women. Borrowers are organized into lending groups that provide social collateral: only one person receives a loan in each group, and the group is responsible to make sure the loan is repaid. Only when the loan is repaid can another member of the group receive a loan. The repayment rate currently is 97 percent.

A recent World Bank study shows that about one-third of Grameen borrowers have risen out of poverty, another third are close, and the final third remain impoverished. The study estimates the cycle to take about five years.

More than 150 organizations have imitated and adapted the Grameen model and are successfully reproducing Yunus’ efforts in 60 countries around the world.

“There is no reason any single person on this planet should suffer the indignation of poverty,” Yunus said. “Poverty is not created by the poor but by the systems. If we are going to change poverty, it’s no use looking at the poor. We need to look at ourselves.”

Looking to themselves for change is exactly what members of the BYU community are doing, and they are finding they can help alleviate poverty through microcredit. Their efforts include creating the first student microcredit organization in existence, writing books and articles, hosting microcredit conferences, doing internships with microcredit organizations, and creating microcredit projects.

“Our goal is to sensitize–to make this a topic of dialogue in the school and to make people at BYU more aware,” says Woodworth. “We can’t just think globally and act globally. We have to think globally and act locally.”

Students have taken that charge seriously. In addition to creating microcredit programs in Cambodia, Bulgaria, Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nigeria, students are creating programs in Utah County.

“One of the things Professor Yunus said when he visited BYU is that you don’t have to go halfway around the world to help with poverty,” says Dave Hanley, a BYU student working on a combined BA/MA in public policy. “We have poor people right here in Provo, and we need to help them.”

In the fall of 1997, three BYU students returned from summer internships with Grameen Foundation USA and created the Grameen Support Group, the first microcredit student organization in the nation. The group hopes to have a microcredit project (its first) running in Provo by March. The more than 70 students involved are researching local needs, examining programs in other parts of the country, and lobbying Provo City for grant money.

“This is not just research, it’s action,” says Hanley, co-founder of the Grameen Support Group. “It is really important that we at BYU are doing something and not just talking about it.”

Another BYU student organization, Students for Responsible Business, also plans to create a local program in a joint effort with students in an MBA policy class.

“As a social worker I worked with a lot of individuals who had skills, but they didn’t have capital,” says David Curtis, a second-year MBA student and a founding member of BYU’s chapter of Students for Responsible Business. “I would get really frustrated because there was nothing at all available to help them.”

Curtis met a man and his daughter living out of their car. The man was a roofer with all the necessary equipment, but he lacked capital to put together even simple marketing materials. Curtis also met a homeless man from Poland who was a European craftsman painter. He had operated a successful painting business until his crew stole his van and equipment and left him unable to complete many jobs and without the capital to purchase more equipment.

“There is no reason any single person on this planet should suffer the indignation of poverty.” —Muhammad Yunus

“We’ve got students here with business skills, we’ve got a local need, and we’ve got professors with talents and interests in microcredit, so why not tap into all the strength we’ve got here and get something going?” asks Curtis.

Microcredit does have a strong foundation at BYU. Woodworth has been teaching microcredit concepts for almost a decade. The movement on campus has gained momentum in recent years as Woller, Adolphson, Gibson, and others have joined him, and together they have formed the Committee to Alleviate Family Poverty Through Microcredit. In addition, the master’s of public management program recently added an emphasis on international development and nongovernmental organizations.

Dozens of students have also gained firsthand experience in internships with microcredit organizations worldwide. Last summer three BYU students worked with the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh.

“Visiting small Bangladeshi villages throughout the country helped me realize the hope found among the poor and their desire to reach higher than their present state,” says Hanley, who spent his summer in Bangladesh. “The Grameen Bank acts as a catalyst for that desire, facilitating the rise from abject poverty to a place where the individual feels more noble. Some critics contest that it does little to help the country as a whole. This may be true. But to the woman who now owns two sets of clothing instead of one, sends her children to school, and feeds her family vegetables, the difference is dramatic.”

“If we can send out students, we can significantly impact the direction of this movement,” says Woodworth, who, with a group of students, recently published Small Really Is Beautiful, a collection of articles about microcredit programs around the world.

“There is a great destiny for BYU,” says Adolphson. “Microcredit is consistent with our values, and if we jump on it, we are going to lead the world in training people to be involved in microcredit. People will be benchmarking against us.”

In a sense that has already begun. BYU is an educational institution member of the Microcredit Summit, the goal of which is to reach 100 million of the world’s poor with microcredit by 2005. For its 1998 meetings in New York City, the Microcredit Summit selected three universities (out of more than 100) to present their plans for helping the summit reach its goal. BYU was one of the universities chosen, and representatives presented a plan that includes adding more microcredit to BYU’s curriculum, placing more student interns in microcredit organizations, and sponsoring speakers and guest lecturers.

In addition to these efforts, BYU hosts an annual microcredit conference, which features presenters from every major microcredit organization in the United States. This year the keynote speaker will be Arun Gandhi, grandson of Mahatma Gandhi.

“No one has the power to completely change the world, but we do have the power, and hopefully the motivation, to improve a small slice of it,” Woller says.

The biggest challenges facing microcredit efforts, including BYU’s, are obtaining start-up funding and working with systems and mind-sets that don’t cater to small-scale entrepreneurs.

“We accept the fact that we will always have poor people around us, so we have poor people around us.” —Muhammad Yunus

“We haven’t traditionally included the microentrepreneur in our economic structuring,” Davis says. “And since our theories and our philosophies and our mind-sets dictate the institutions and the environments that we create, there isn’t a favorable legal or regulatory environment anywhere for someone on the street who wants to sell hot dogs and Cokes.”

But Yunus rejects the idea that things can’t change. He sees these obstacles as man-made and therefore man-alterable through efforts like those of BYU and others committed to ending poverty.

“We accept the fact that we will always have poor people around us, so we have poor people around us,” Yunus told graduates and guests at BYU’s August 1998 commencement. “If we had believed that poverty should not belong to a civilized human society, we would have created appropriate institutions and policies to create a poverty-free world. We wanted to go to the moon, so we went there. . . .

“We can create a world where there won’t be a single human being who may be described as a poor person. In that kind of a world, the only place you can see poverty will be in the museums. When school children will be on tour of the poverty museums, they’ll be horrified to see the misery and indignity of human beings. They’ll blame their ancestors for tolerating this inhumane condition and allowing it to continue in a massive way.”

In a 1997 address at BYU, Yunus said, “I hope our generation will be the last generation that will see wide-spread poverty on this planet. And from then on, we will give to the next generations a world where poverty is just a word.”