Using an animated, big-lipped fish named Marla, BYU researchers are teaching children with autism the steps of conversation. Photo by Bradley Slade.

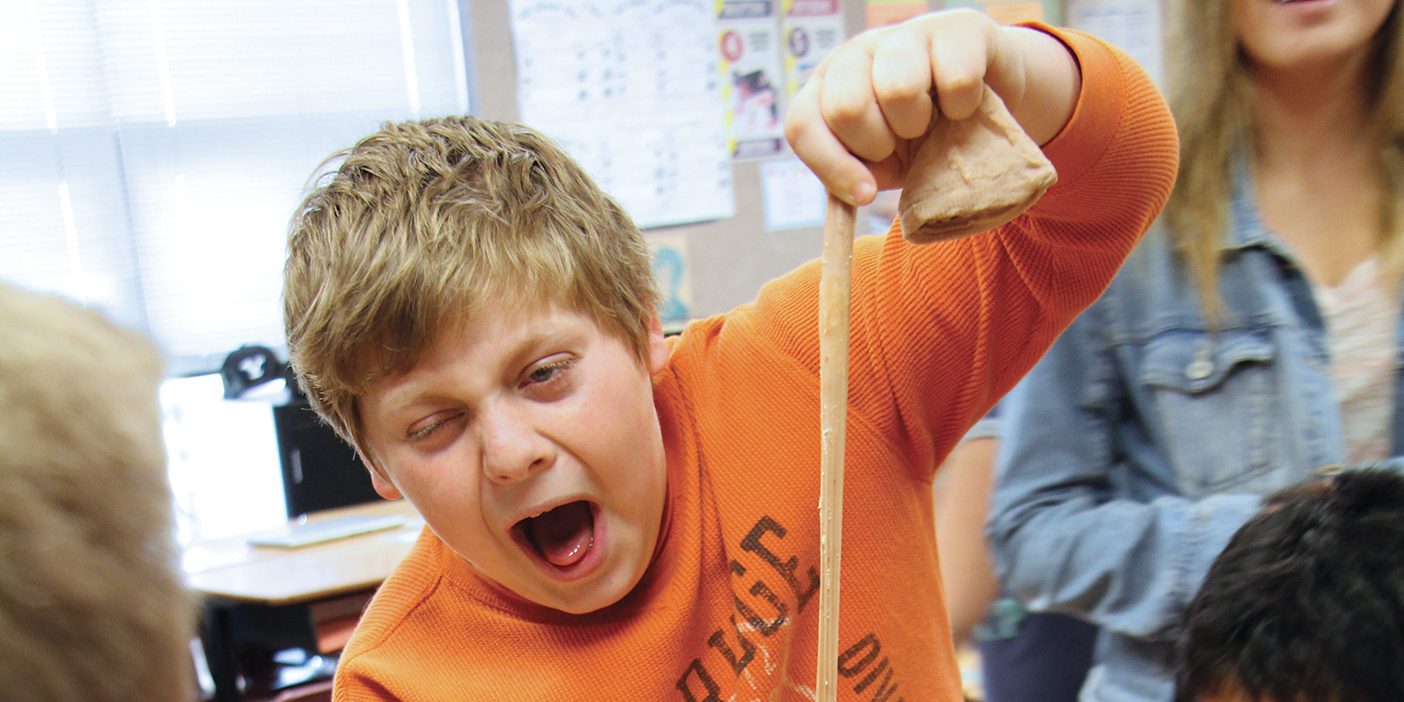

“Hello! My name is Marla. What’s your name?” says a fish. Jack, 8, begins to talk with the wide-eyed purple character swimming on the screen in front of him. As Jack talks, Marla pauses and listens, locking eyes with Jack and smiling widely. The fish never misses a beat, responding on topic, then asking Jack questions about his favorite candy and answering Jack’s questions about her own fishy favorites.

Marla, controlled by a student behind a one-way mirror, is a part of a study led by counseling psychology and special education professors Ryan O. Kellems (BA ’04) and Cade T. Charlton that uses the animated avatar to teach social skills to children with autism.

Many children with autism struggle with aspects of conversation, like maintaining eye contact, positioning themselves at an appropriate distance, not fidgeting, and actively listening and responding. But Marla is a great coach. And for children with autism, an animated character provides a “low-risk environment,” Kellems says. “It’s different when you’re talking to somebody who’s not going to judge you.”

The researchers control Marla with an electronic pad by clicking different areas with a stylus to make the fish move, blink, and show exaggerated emotion. They touch a square marked “happy” and Marla smiles, “sad” and her eyes and mouth droop. They speak into a microphone and Marla’s mouth moves accordingly. Marla walks the children through five steps of starting a conversation: look at the person and smile, stand an arm’s length away, use a nice voice, ask a question, and wait your turn to talk.

“Our goal was never just to teach them to talk to a fish.” —Ryan Kellems

Jack’s mother, Amy Tanner Omer (BA ’02), says, “He really lightened up with the fish and got more creative in asking questions and answering questions.”

And not just with Marla.

“Our goal was never just to teach them to talk to a fish,” says Kellems. After practicing with Marla, the kids practice with a student researcher, and, later, a child the same age. In social situations, even with peers, kids with autism typically avoid interaction. “When we actually saw them start a conversation with the other kids, that was a really neat experience,” says Kellems. And for some, he adds, it was “a really touching moment . . . when the kids would then start conversations with their moms.”

Kellems and his team of student researchers have presented their findings at national conferences—a feat for undergrads—and are planning studies with humanlike avatars. But Kellems sees no reason to wait to implement such tools in homes and schools: “We have this great technology, but we’re not leveraging it to help individuals with disabilities.”

Meanwhile on campus, Jack and his mom are en route to get ice cream, cousins in tow. “You’re going to have a conversation with Miles, okay?” Omer says. “Do you remember the steps?” At first Jack stays quiet, looking down as his cousin Miles talks about his favorite color and food. But after a few minutes, Jack begins making eye contact and sharing his own favorites—the color red and cookies-and-cream ice cream, orange trees and the app Clash Royale (“There’s 2v2 rounds and battle rounds and arenas and you can have cards . . . ,” he explains).

Thanks to Marla, for a moment they’re just two kids talking about Lego sets and popcorn flavors, on their way to get ice cream in July.