By Lisa Ann Jackson

As sunlight floods the colored glass, hues of reds, blues, greens, and ambers splash across the walls and pillars surrounding the windows- windows of stained glass set as the backdrop to the new Orem City Children’s Library.

Giving life to favorite fairy tales, Ralph Barksdale of BYU’s design faculty and Tom Holdman of Holdman Studios in Orem spent a year and a half designing, illustrating, and setting to glass a collage of children’s stories.

In the windows, Sleeping Beauty lies draped over a plush pallet with the prince at her feet; Little Red Riding Hood grabs at her cape as she passes the wolf; Puss ‘n Boots slyly grins while a princess looks leery-eyed at an approaching frog; and a grand wizard robed in royal blue oversees the bustle in his quiet majesty.

“The window was designed to draw people into literature,” says Dick Beeson, director of the Orem City Library. “It was meant to bridge that gap from the visual world to literature.”

But the artists found they were bridging not only visual and literary gaps but also a gap between the stained glass techniques used in Gothic cathedrals and those developed by Louis Comfort Tiffany during the late 19th century.

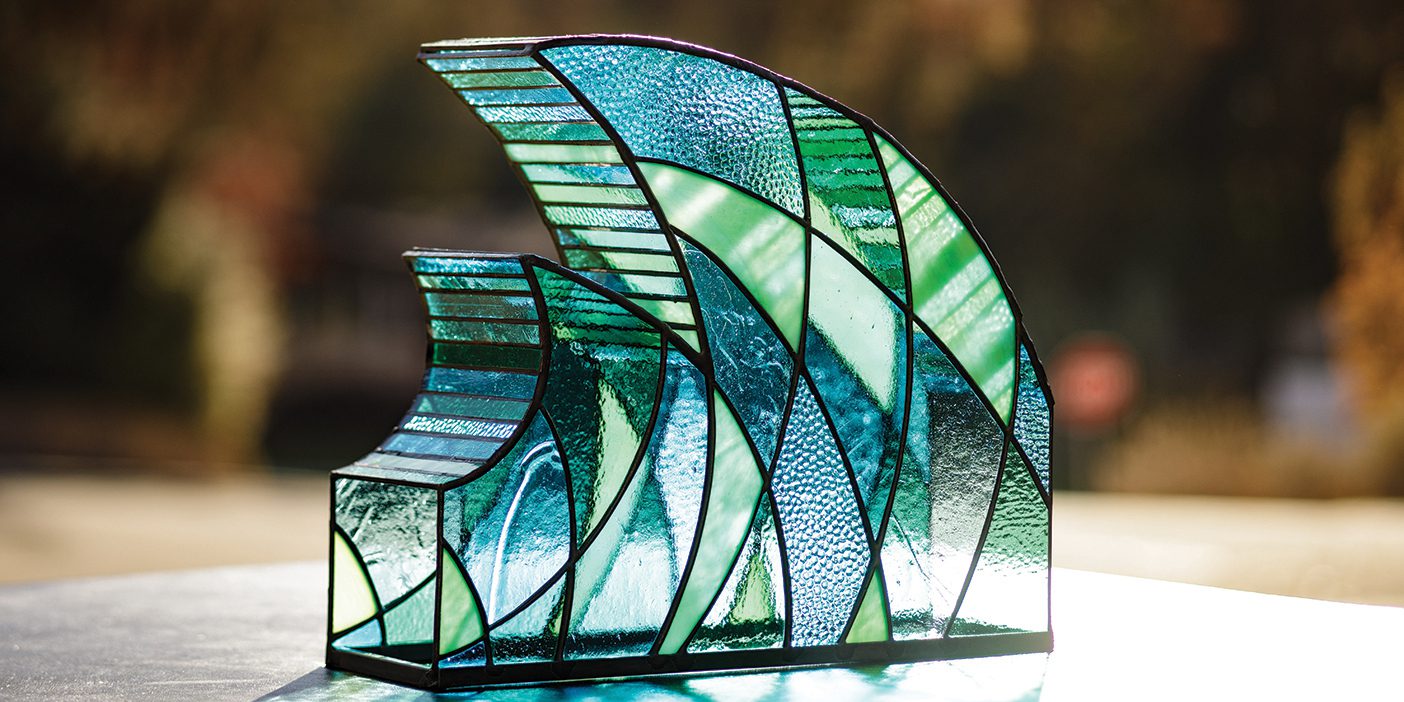

Capturing children’s stories and fairy tales in glass windows, a BYU faculty member and a local artist created eight stained glass windows like the one above for the new Orem City Children’s Library. The windows took 18 months and 5,000 pieces of glass to complete.

Beginning in the 12th century, stained glass workers put small pieces of translucent glass together with lead, producing colorful mosaics depicting sacred events and themes. Through the centuries, artisans increasingly used paint to achieve detail and perspective in windows. By 1800, however, paint had virtually taken over the window, ruining the interplay between light and colored glass.

Tiffany rejuvenated the art of stained glass by limiting the use of paint and once again approaching the window as a mosaic of colored glass. In addition, he invented opalescent glass, a semi-translucent glass containing variations of color within the glass itself. Tiffany style reignited interest in the dying art form, so much so that stained glass increasingly appeared not only in religious but also in public and residential architecture.

Tom, who chose the style of the Orem library window, was particularly inspired by a window in the National Cathedral in Prague, Czechoslovakia, a stained glass collage of figures created before paint became overbearing. He decided to follow a realistic style not unlike that of Tiffany, yet without the loss of translucency, and to harken back to the centuries-old tradition of painting on glass. Not realizing the challenges the pair would face in resurrecting the old style, Tom approached Ralph to illustrate and paint the window.

“We needed help with the painting and all of the design work,” says Gayle Holdman, Tom’s wife and an often-volunteered partner in his projects. “We had known Ralph as an excellent artist, so we asked him if he would work with us in putting Tom’s and Ralph’s abilities together.”

Despite Ralph’s background in art and Tom’s experience with glass (which stems from a stained glass unit in a high school art class and years of self-training), the task of resurrecting the centuries-old stained glass technique of painting realistic figures on glass was daunting. In all their searching, they were unable to find anyone who had recently attempted a painted window like those of the European Cathedrals.

Finally they found Virginia Gabaldo, a stained glass artist they met at a convention in Las Vegas, to introduce them to new painting techniques. What Ralph and Tom were not able to learn from her, they simply had to teach themselves. Doug Soelberg, a stained glass worker from Orem, assisted with constructing the window as did Tom’s wife and Ralph’s family members.

“This thing was the big training ground,” Tom says, adding that he feels he could do almost anything in stained glass after all he learned working on the two 8H-by-18-foot windows made of 5,000 pieces of glass.

Ralph’s training began when he had to actually paint the illustrations he had designed for the windows.

“It’s totally backwards,” Gayle explains. “You don’t take your paint brush and put on the paint where you want it. You put on a lot of paint and then take your paint brush and take it off where you don’t want it.”

“After crying for many weeks after he told me what was going to have to be done, I thought, This is absolutely opposite of what a painter does.” Ralph says.

The paint–which is actually glass itself–is like dust. “It’s dry and dusty and you just whiff it away with your brush and then fire it in a kiln,” he says.

The result is translucent lines and colors, allowing light to breathe life into the painted figures.

“It’s as close as the artist will ever get to painting with light,” Ralph says.

Just as the paint has a technique of its own, the artists often found that the glass, pre-colored stained glass imported from Germany, had a mind of its own as they tried to fashion it.

“Sometimes the glass cooperates in an interesting way–like it has a mind of its own, thinking, I would look better like this, so I’m going to break for you right here,” says Gayle. A few times the glass broke in places where the artists hadn’t planned to join pieces together, but by connecting the broken pieces together with lead, they added accents even better than those originally designed.

But the breaks were not always so helpful in adding character, nor could they always be blamed on the glass’s free agency. One of the largest single pieces of glass in the window–on which is painted a knight’s helmet- decided to break irreparably after a week of work. They simply had to begin again. Another finished piece of glass shattered under the pressure of a fly swatter–Ralph was trying to swat a wasp, forgetting the wasp was on imported German stained glass.

But beyond the challenges of learning techniques no longer in common practice and working with a sometimes volatile substance, Ralph and Tom are pleased with what they accomplished in the children’s library.

“I had one of the library people come right here, standing at my side, and I heard, ‘sniff, sniff,’ and I looked over and she was crying. She said she cries every time she comes up to the window,” Ralph says. “That’s great. That’s a lot of satisfaction.”

“It brought tears to my eyes,” Gayle says, “just to see it, and watching them, knowing what went into it, and seeing the satisfaction that everybody else had.”

Much of the satisfaction comes from the child library patrons for whom the window was created.

“If the children like it, that was what the whole point was because it’s a children’s library. If it gets them excited and they can relate to the figures and relate to the whole imagination scene, then the goal was reached,” says Gayle.

“Art for me has always been a tool to speak to people, because I have a speech impediment,” says Tom.

Spending just five minutes watching children run up to the window shouting, “Look Mommy!” or listening to two girls debate the identity of a character proves that these artists have spoken–they have spoken to the imaginations of their young patrons.