An Ode to the Y

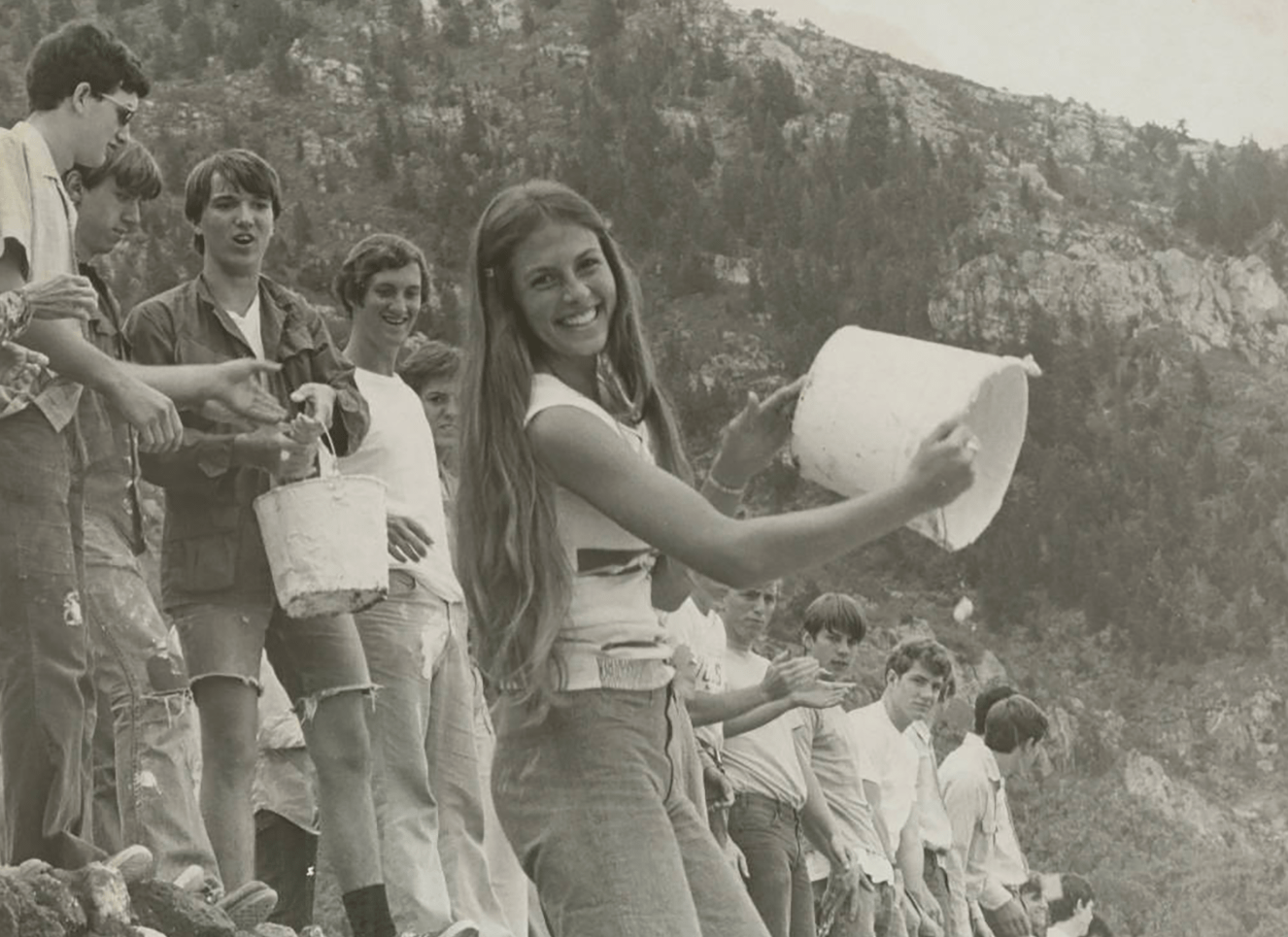

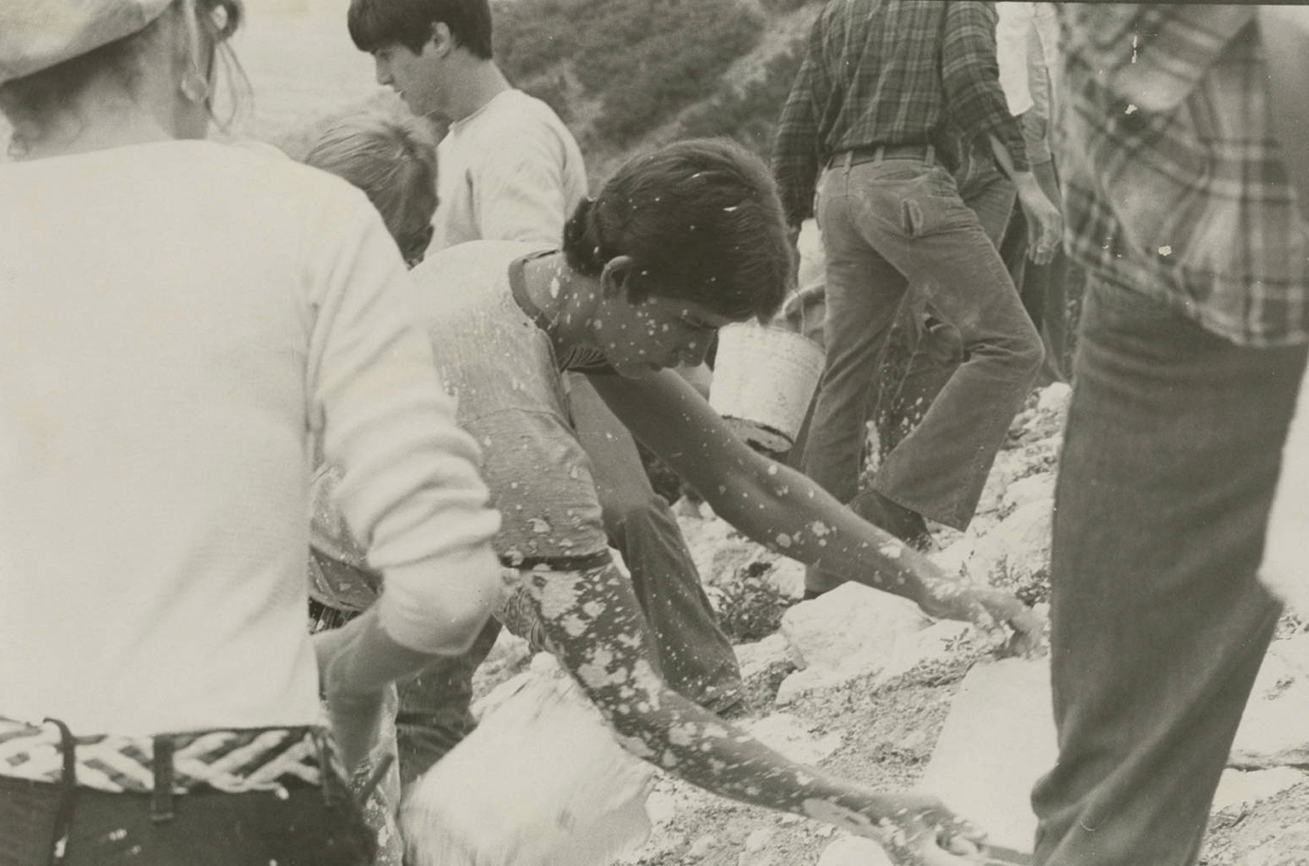

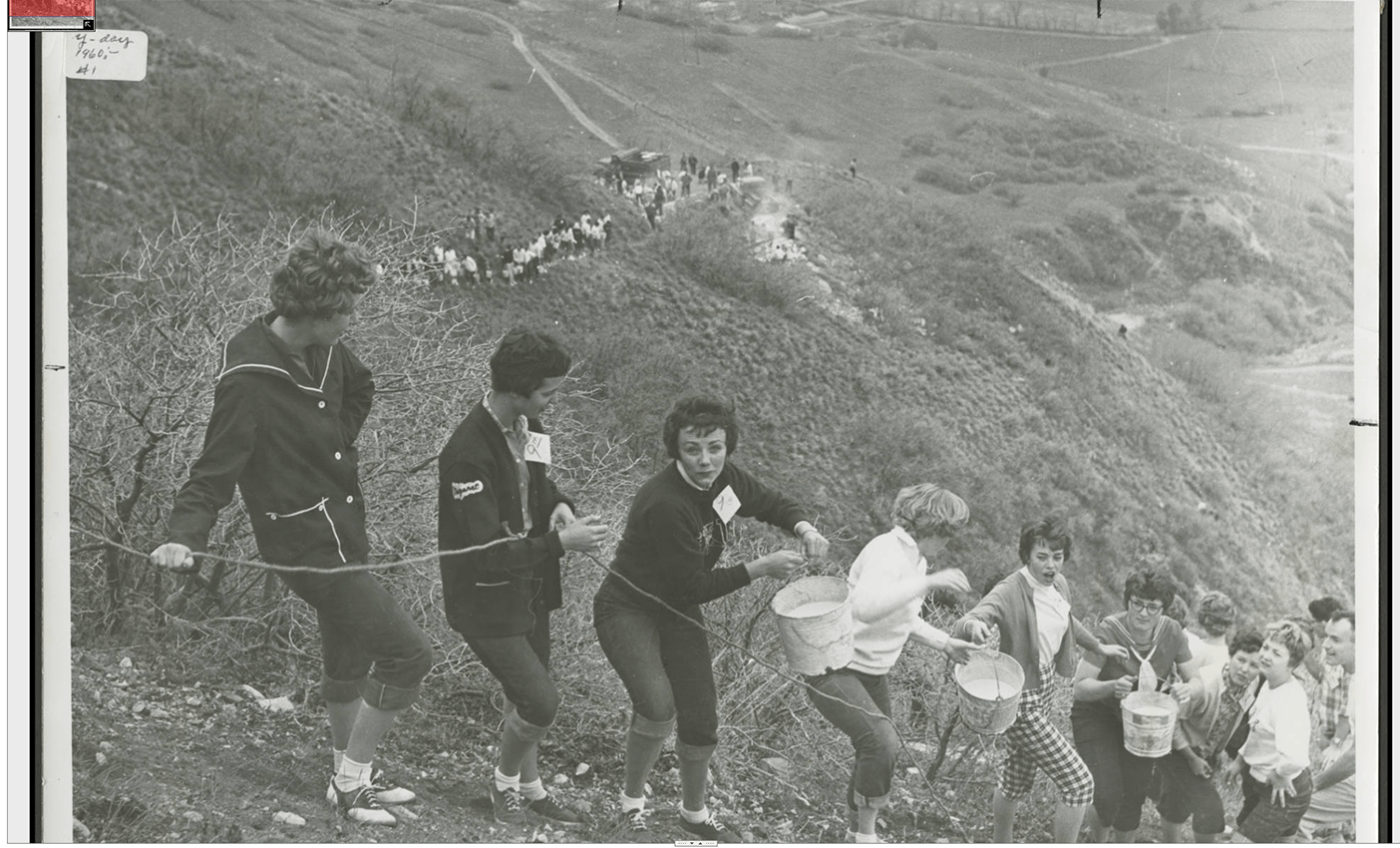

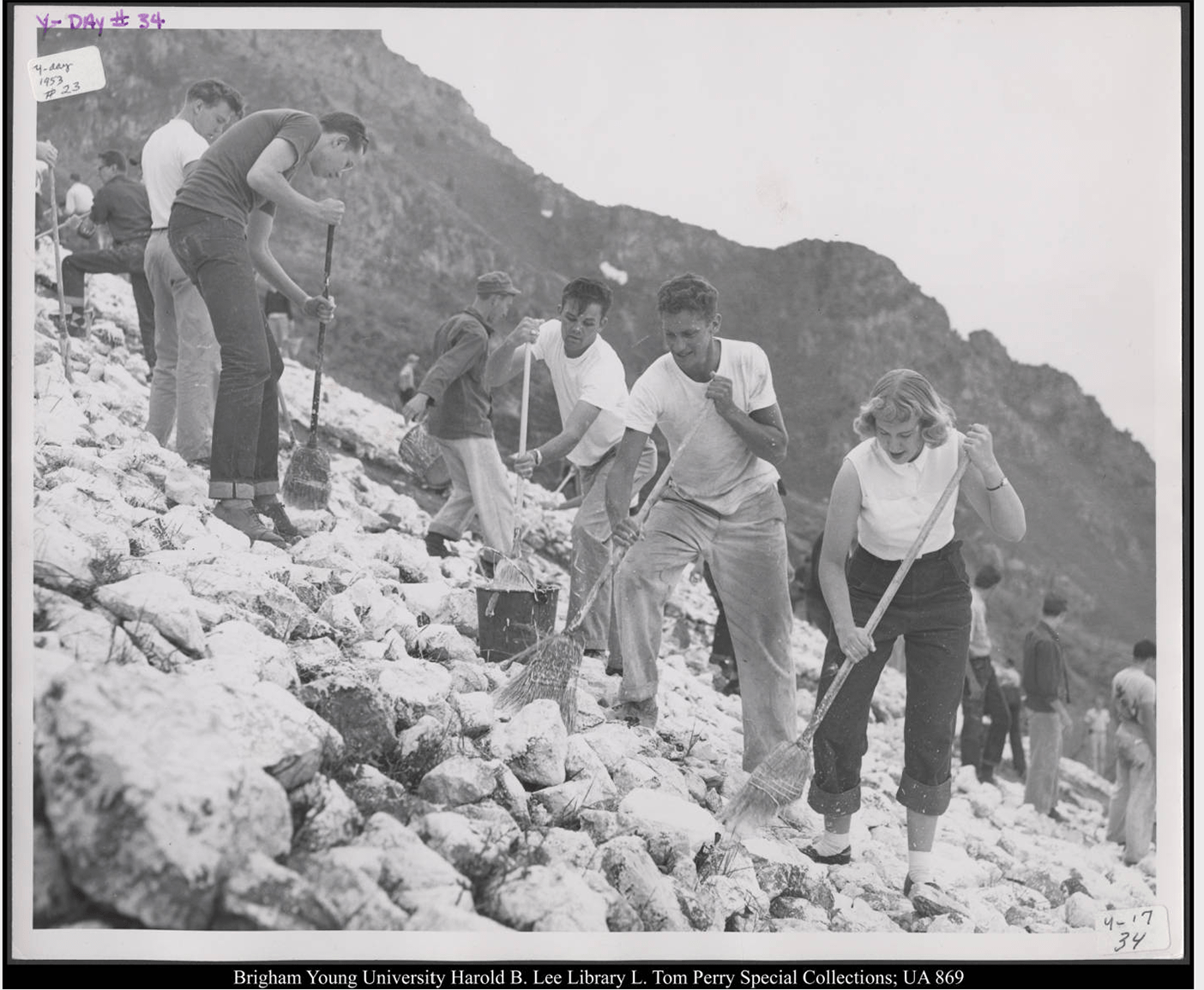

In honor of BYU’s recent purchase of and renovations to the Y and the Y Trail, we offer here a primer on everything you never knew about BYU’s beloved symbol on high.

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04) in the Fall 2016 Issue

Photography by Bradley H. Slade (BFA ’94)

If you look closely at Y Mountain’s namesake letter east of campus, you’ll see that the two arms of the letter form a brush-filled, negative-space arrow, which points downward at a 28-degree angle into Utah Valley. Draw a line from the arrow straight down the mountainside, over craggy cliffs and east-bench dwellings and slicing across town, and the arrow points, unsurprisingly, to the Provo City Library block on University Avenue. Unsurprising because that city block—featuring the restored BYU Academy Building—housed the BYU campus when the massive letter was dreamed up, surveyed, and constructed in the spring of 1906. The students who built it aligned the initial perfectly for their viewing enjoyment.

That line, extended out, eventually reaches Hawaii and Australia and, as it wraps back around, runs right through New York City, Cleveland, and Chicago. And yet, be it fancy or egocentrism or evidence that I’m just plain crackers, I’ve sometimes had the feeling that that mountain symbol is pointing at me. In fact, long before I ever knew there was a BYU, let alone a solitary block Y on a mountain, it was there, pointing straight across salt deserts and snow-capped Sierras to me in the Bay Area, where it had also beckoned to my parents from afar decades before.

After heeding its call to Happy Valley as a freshman, I caught it pointing my way one early-autumn afternoon. With a magnetic pull, the Y drew me on a meandering path through Tree Streets, up pitched roads, and—after a dead end or two—to the base of the Y Mountain Trail, which I set out on, taking little notice of approaching thunderclouds. Trailside scrub oak provided poor shelter from the downpour as I soggily scanned the valley below—a patchwork of verdant fields giving way to the city grid melding into campus quads rising up into blocky dormitories leading the eye to silver stadium stands and the expanse beyond. The Y, it seemed, had brought me up the mountain to introduce me to my new home, freshly bathed and gleaming under streaks of sunlight.

Following a mission I lived for two years in an apartment on 7th North and 5th East, directly beneath the gaze of the Y. During those happy days, as I stumbled my way into a major, an engagement, and my first job as an editor, the full BYU experience seemed to be aimed squarely at me.

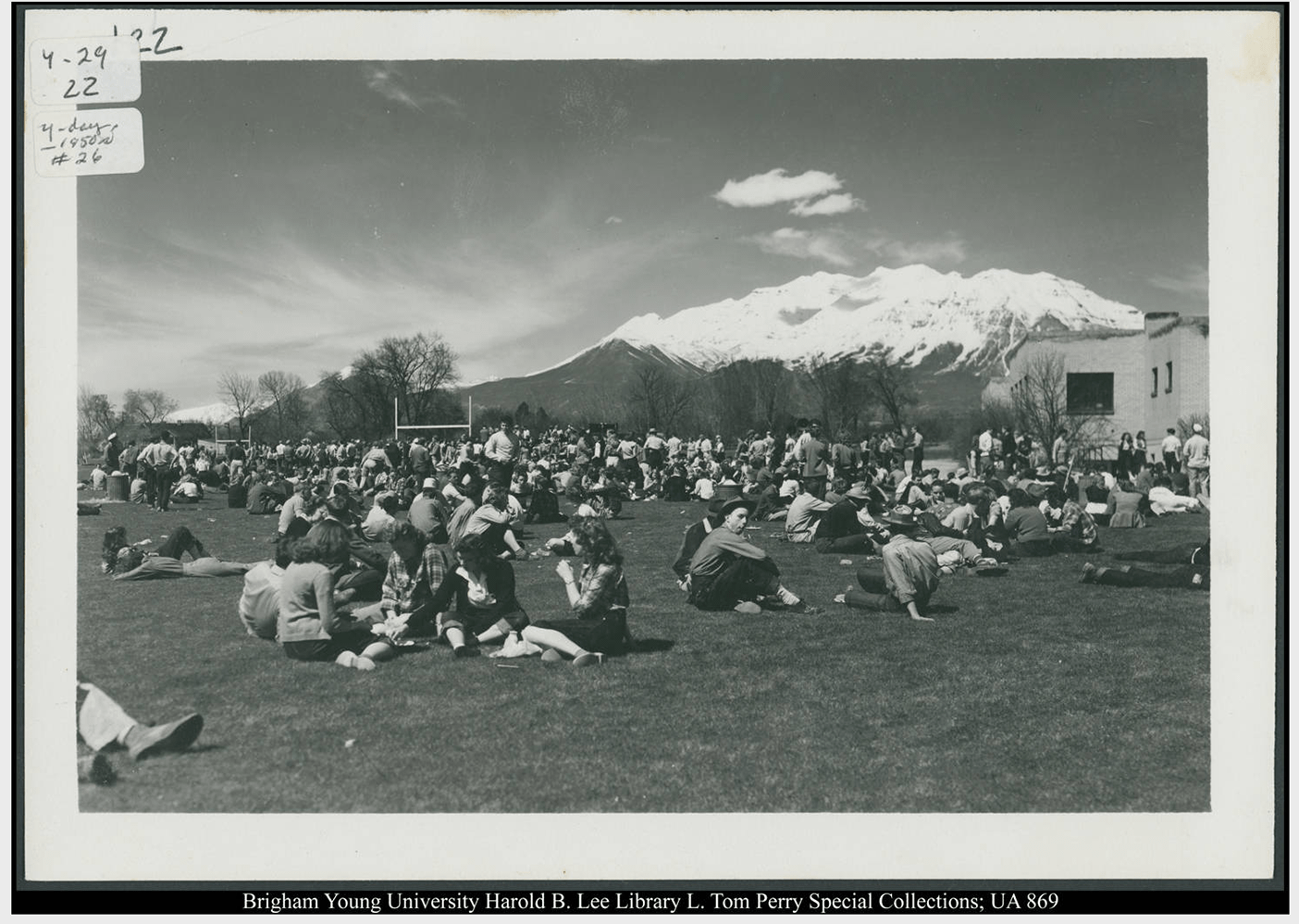

But, of course, countless others have also found themselves in the Y’s crosshairs, the mountain letter catching their eye and lifting their expectations. Just as it did to me, for more than a century the Y—and the university it represents—has called to hundreds of thousands of young people: Come to the foot of the mountain—where you can wonder and question and explore and struggle and worry and expand and cheer and love and, ultimately, find your future.

A symbol? Yes. A placemark? Sure. But much more, the Y stands as an invitation, beckoning all to come to the mountain and to climb.

“Why not . . . place a Y on the mountain side that will signify to the citizen and tourist that, nestled ’neath the snowy peaks is an institution of which we are justly proud.” —In The White and Blue, April 27, 1906, p. 187

Y Origins

It all began in the predawn hours of a spring 1906 morning, when, in an audacious prank, a group of Brigham Young High School juniors snuck onto the mountain with bags of white lime to leave their mark—’07—for all to see. Using epic language, junior students later described the effect of their shenanigans in the pages of the student paper, The White and Blue:

How what [the student body] saw aroused it! It sprang to its feet in angry amazement; the whites of its eyes gleamed like lightning. Its generals too, short, medium, and husky, quivering with pent-up desire, stood quivering. . . .

. . . They ran to the four winds with flaming banners, and crying: “Assemble, ye hosts, prepared to fight!”

The war-cry answered from supper halls, from study dens, and byways. As if by magic, the roaring multitude ran together. . . . So great became the tumult that every living thing, every craftsman, peasant, pedagogue, pedagoguee, from Dan to Bersheba knew that the class of 1907, by placing its emblem on the hill, had stirred the Brigham Young University Student Body to the center. [May 25, 1906 (vol. 9, no. 11), pp. 216–17]

An all-day mountainside altercation ensued as the student mob demolished the numbers and shaved a few ’07 heads, returning down the mountain victorious. Or so it seemed. When Provo awoke the next morning, the ’07 was there again. Following another student “stampede” up the mountain, BYU president George H. Brimhall (1877) and Brigham Young High School principal Edwin S. Hinckley (ND 1891) suggested a compromise: why don’t all the classes band together and put the letters B, Y, and U on the mountain instead?

The juniors claimed this was their “pet scheme” all along: “The B. Y. U. emblem ought to be put on the mountain this year,” they wrote in The White and Blue, “but the necessary enthusiasm must first be aroused—the ’07’s have aroused it” (p. 217).

The Y’s Peers

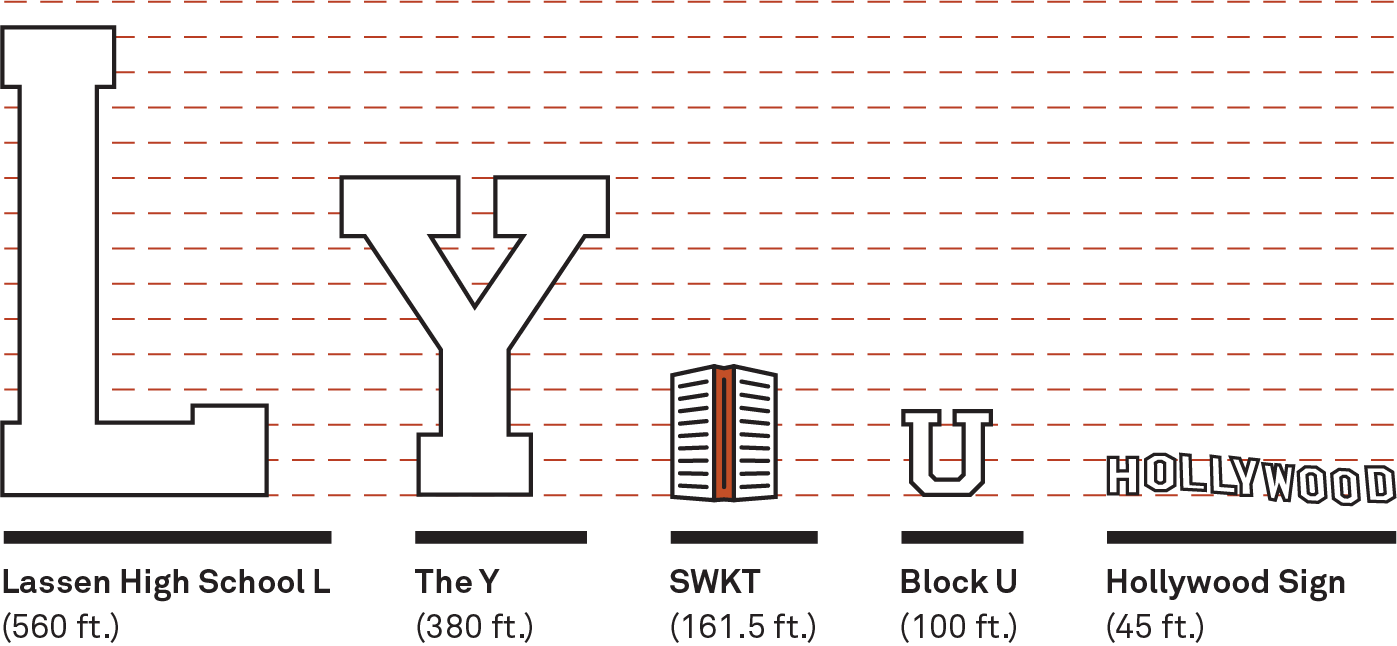

Dotting the hills and mountains of the western United States are more than 500 mountainside letters, marking universities, high schools, towns, and attractions. The Y isn’t the oldest or largest of them—but it’s pretty close on both counts, says BYU geography professor and cartographer Brandon S. Plewe (BS ’92), who created the Wikipedia page “Hillside Letters.”

The first, constructed in 1905, was UC–Berkeley’s 60-foot Big C, which BYU faculty saw while visiting the campus. It was the inspiration for a temporary letter constructed at the University of Utah a few weeks later (replaced with a permanent letter in 1907) and for the Y in 1906. All three were created as part of efforts to unify rival classes at the schools.

The largest letter, at approximately 560 feet in length, is the Lassen High School L in Susanville, California. The Y comes in fourth, at 380 feet. The Block U in Salt Lake City is approximately 100 feet long.

Y Trail by the Numbers

BYU has maintained the Y Mountain Trail for decades, but its recent purchase of the land from the U.S. Forest Service has allowed the university to make more significant improvements—repairing sections affected by erosion, adding a more durable surface of gravel and dirt, and placing new signage at each turn. But the hike remains the same lung-busting bucket-list item that has motivated students and the larger community for more than a century.

One-Way Distance: 1.06 miles

Elevation Gain: 1,074 feet

Average Grade: 18.7 percent

Switchbacks to the Y: 10 to the base; 12 to the top

Toughest Stretch: Switchbacks 4 and 5 (119 feet gain in just .09 miles, a 25 percent grade!)

Time: 30 minutes to an hour each way

Fastest Climb: You tell us. BYU Magazine has created a page on a fastest-known-time website where hiking feats are logged. You can add your best times to the top of the Y at more.byu.edu/Ytrail.

Just Our Type

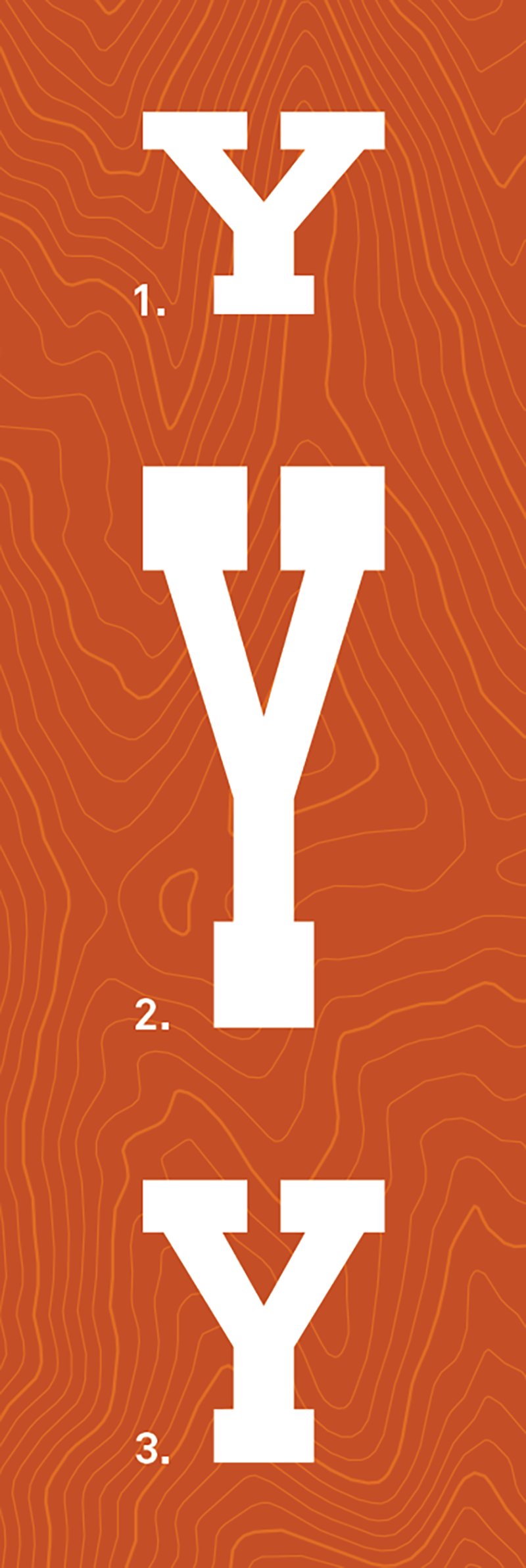

Asked to describe the Y’s type style, BYU design professor Brent K. Barson (BFA ’97) and adjunct design professor Douglas B. Thomas (BFA ’08) call the simple, evenly weighted capital a reflection of the era it was drawn up.

Font family: Egyptian or Antique, a common general type style from the 19th century

Style: Geometric, with its symmetrical, evenly weighted arms

Similar modern fonts: Giza, Rockwell, Memphis

Slab serifs: Added in 1911, the large serifs followed an early-1900s trend of using block letters in collegiate typography.

Font size: In typography 1 inch = 72 points; so at 380 feet, the Y is a 328,320-point letter.

“I am . . . , as a Yale graduate, thrilled to see that big Y up on your mountain. It was extremely thoughtful of you.” —Pulitzer Prize–winning author David McCullough, in a 2005 BYU forum address

A Y of Perfect Proportions

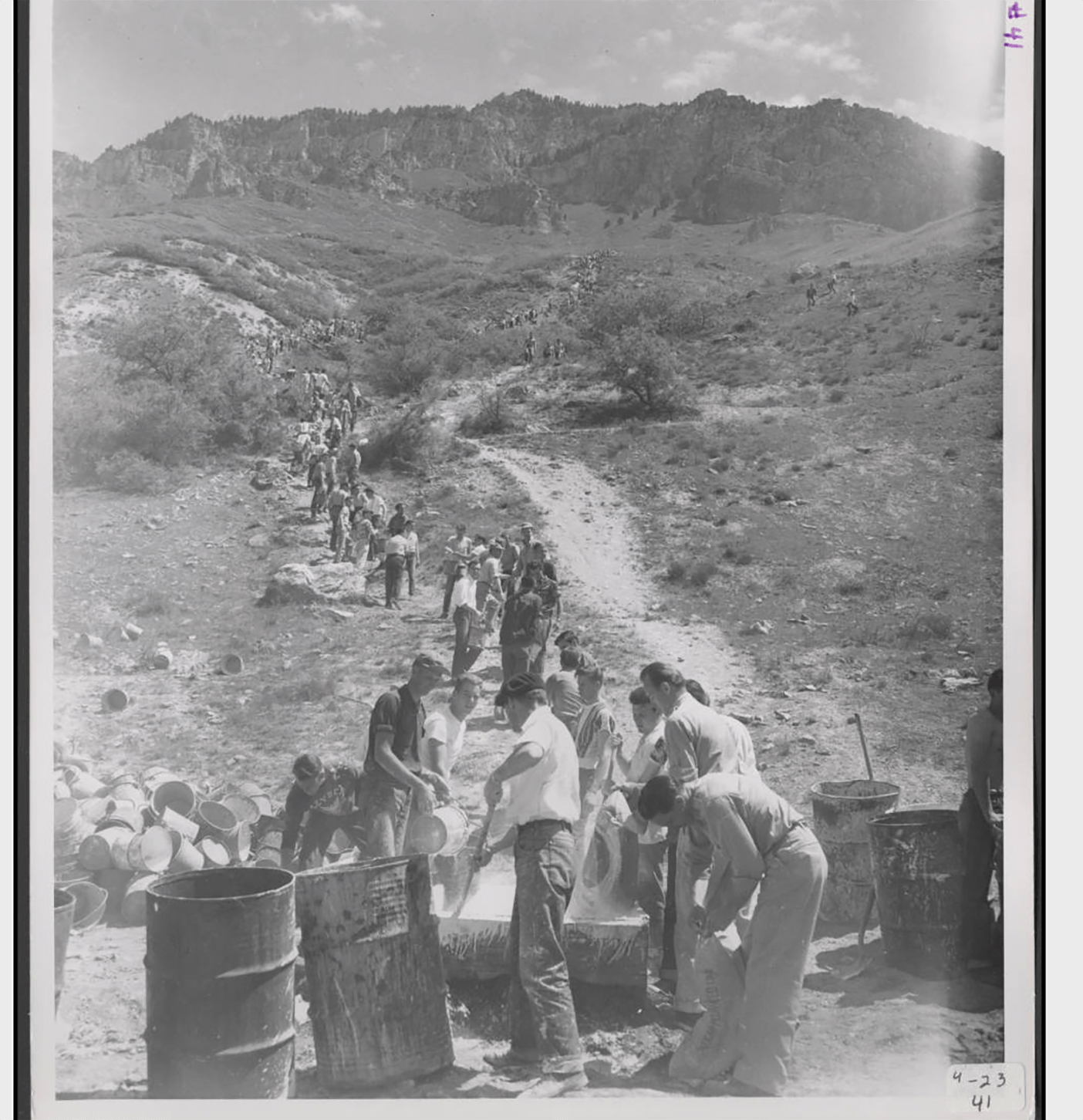

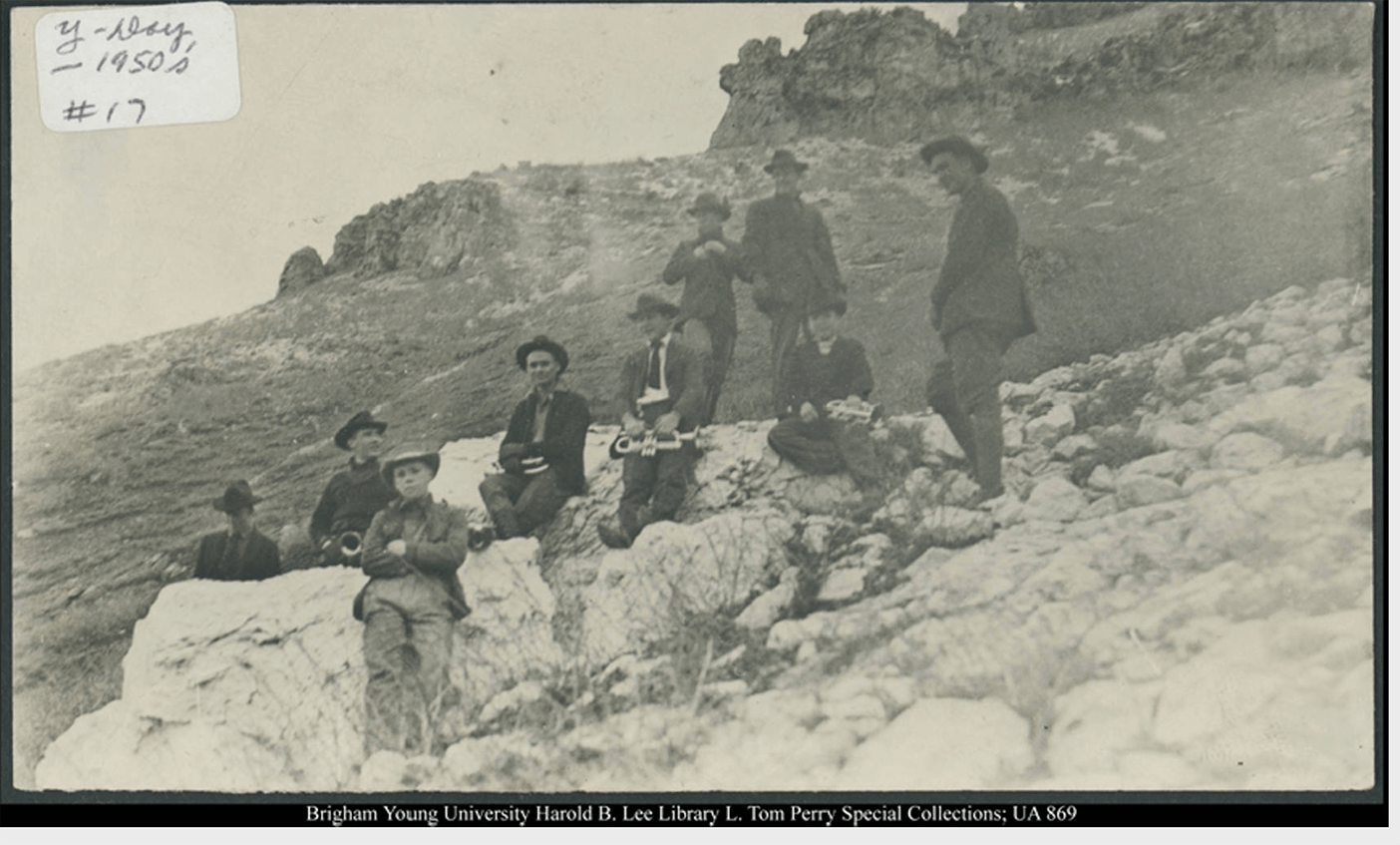

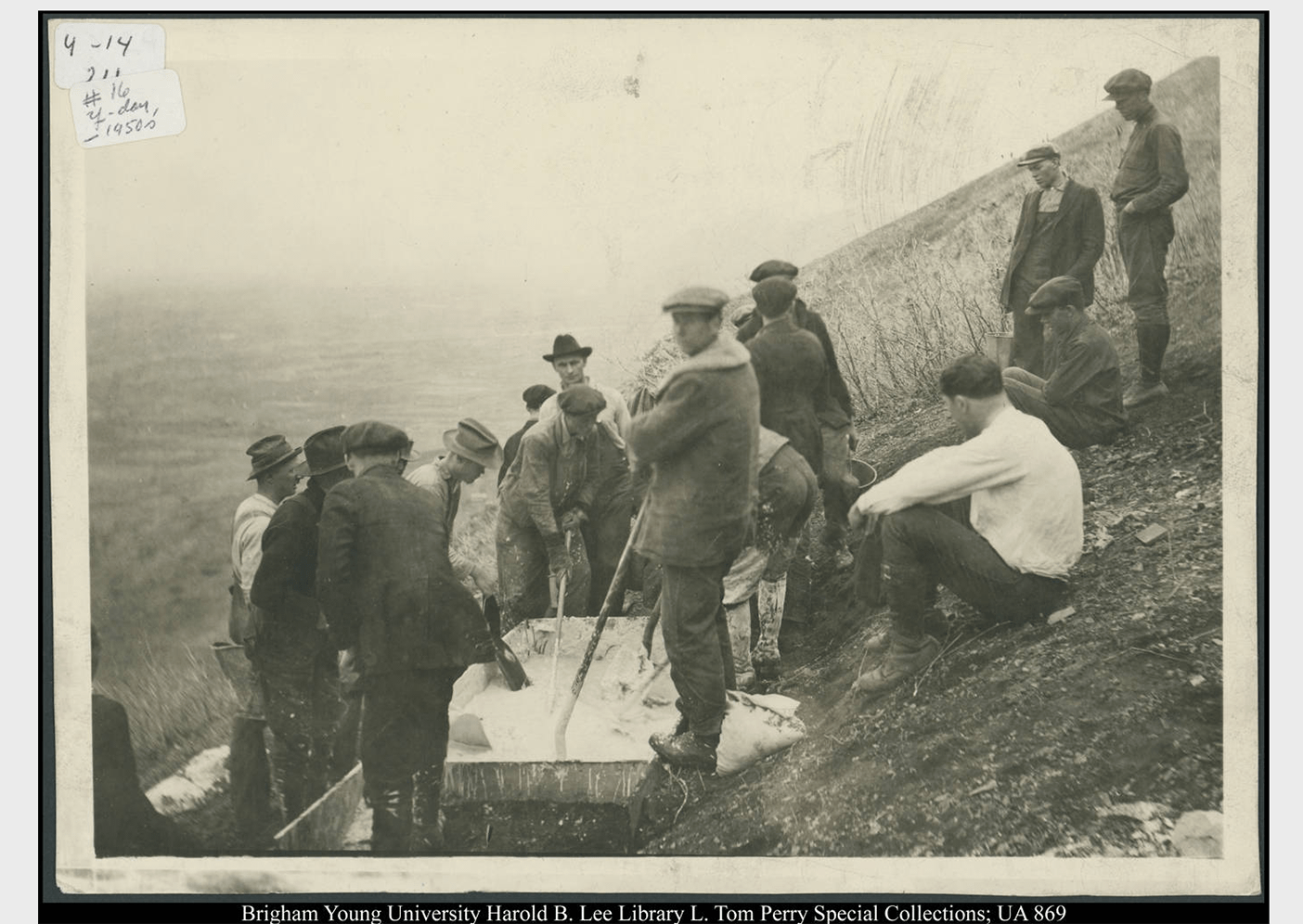

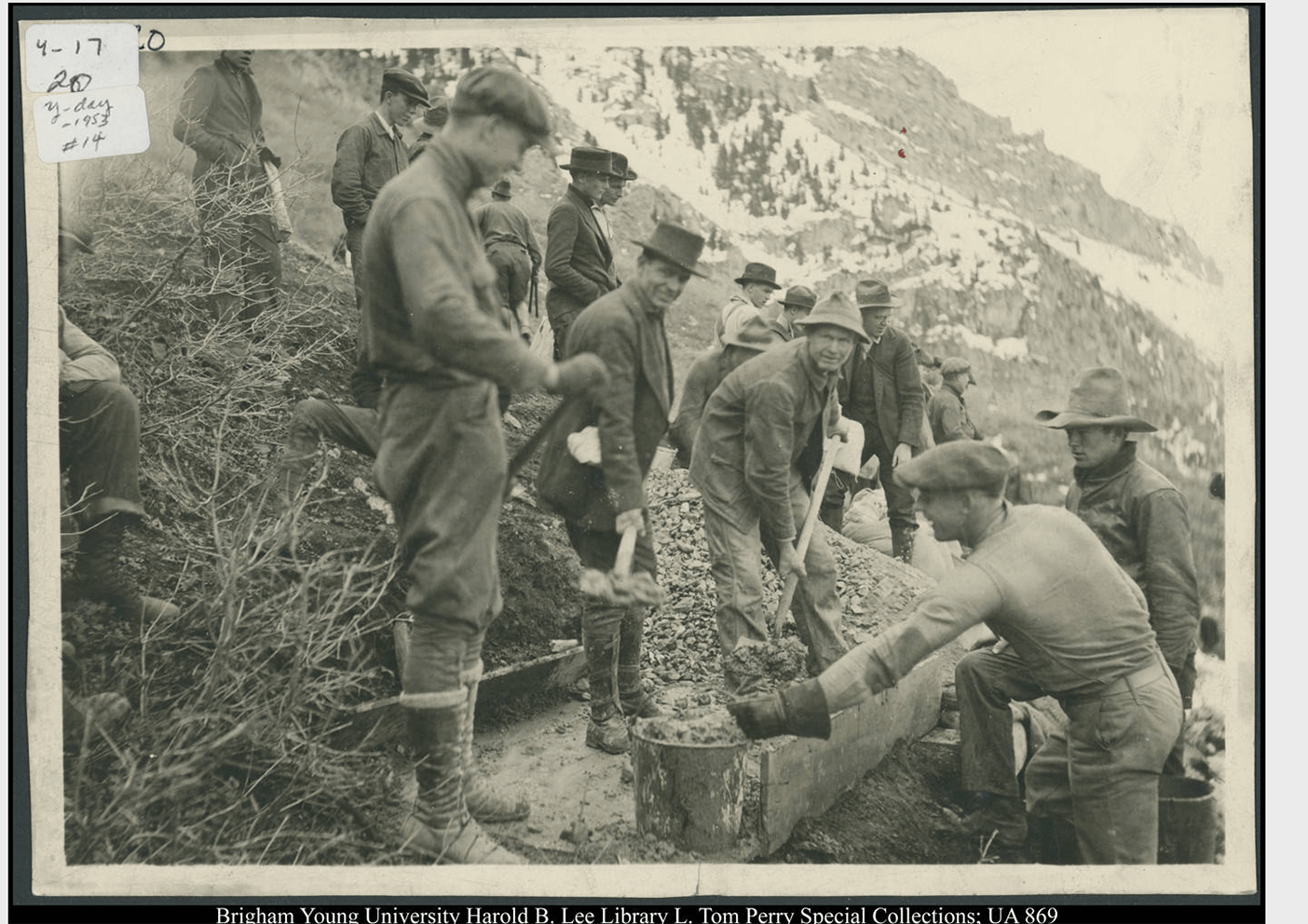

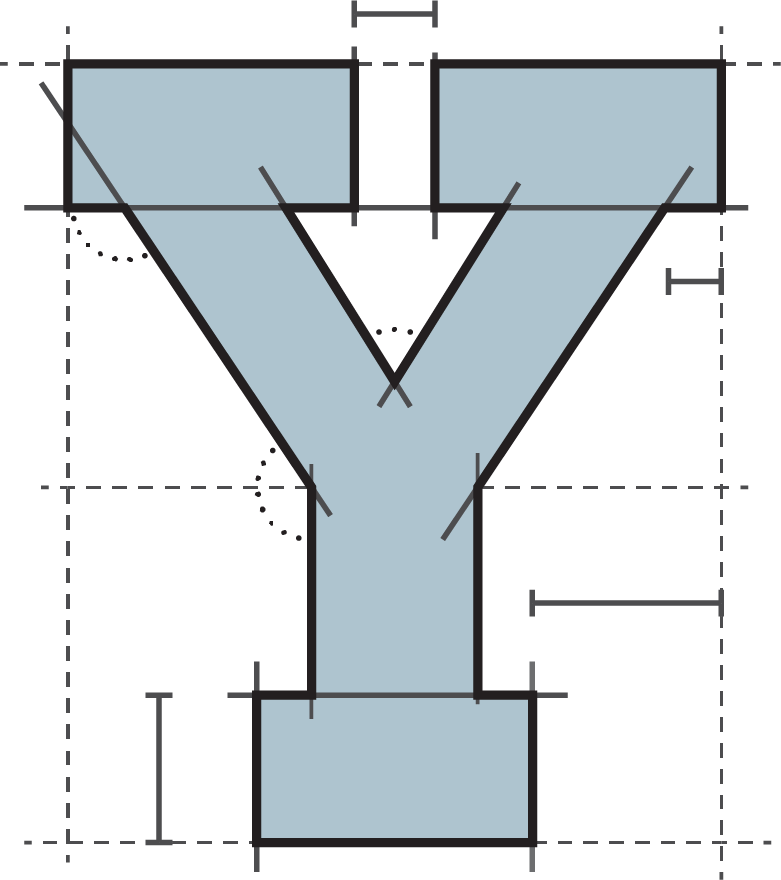

This can’t be right. So exclaimed the student officers leading the band of 400 BYU young men and faculty in the predawn light of a May 1906 morning to put their stamp on the mountain. Staked and already outlined in rock on the steep slope, the shape—at approximately 330 feet tall and just 25 feet wide in the stem—appeared far too slender to their eyes. If they built such a lanky letter for the whole valley to see, they’d be laughing stocks.

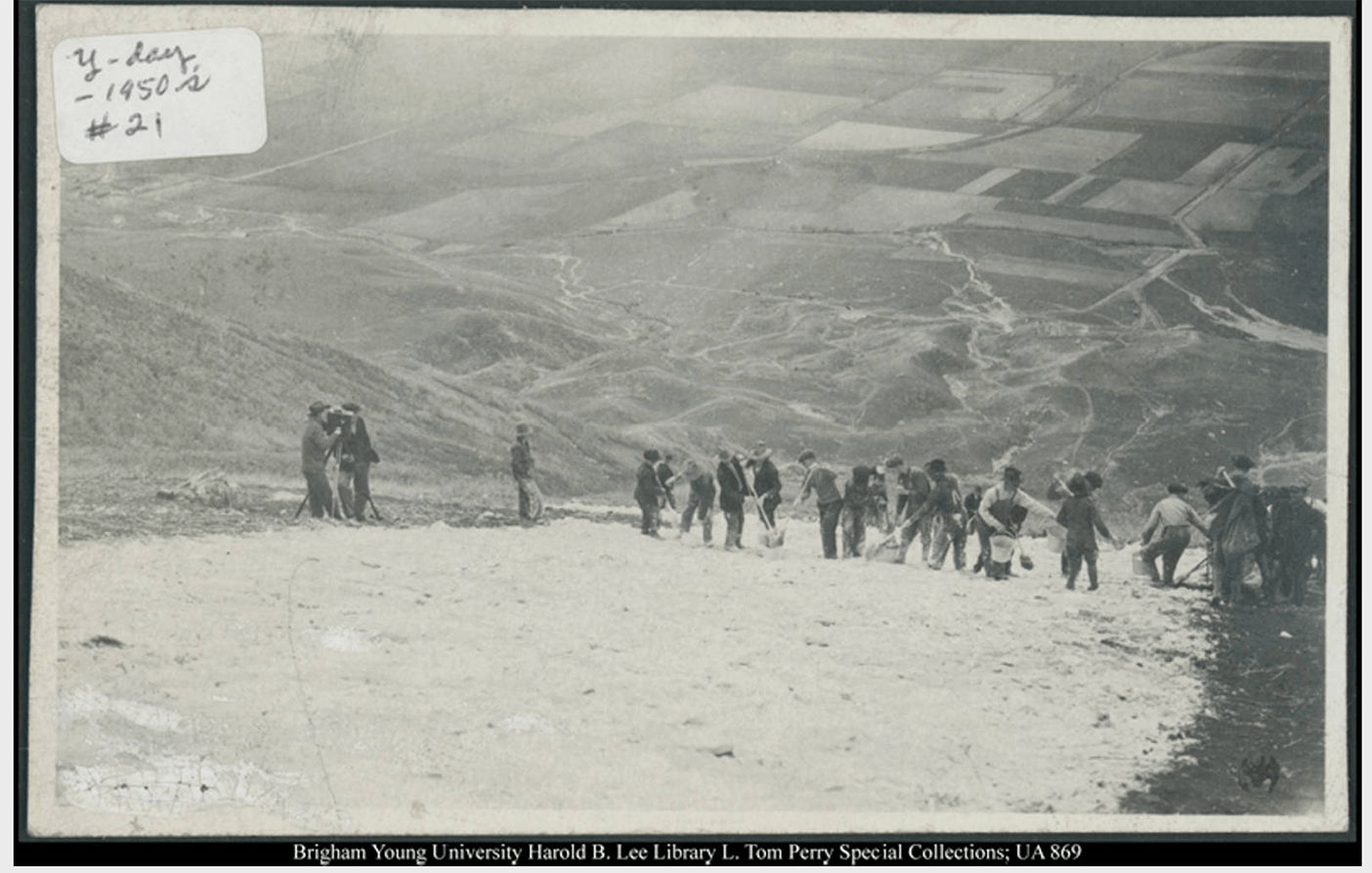

So they called down the brigade line for Elmer A. Jacob (1908), student body president and a member of the surveying team (which also included his brother Clarence C. Jacob [BA 1909] and future famed scientist Harvey Fletcher [BS 1907], overseen by their drafting professor, Ernest D. Partridge [BD 1897]). Elmer scurried up the mountain for a breathless debate. Only when he had convinced them that the letter had been proportioned for viewing from lower campus—not from the mountainside—did they allow the army of workers to begin passing up rock and sand and lime.

To get their measurements, the surveyors had put a level transit at a designated point on the mountain and set a telescope on the flagpole atop the Academy Building on lower campus to read the inclination angle for their calculations. According to BYU adjunct professor of civil and environmental engineering Harold D. Mitchell (BA ’71, MS ’91), they took into account both the angle of the Y to their position in the valley and the slope of the mountain. Here’s the math they would have used to create an aesthetically pleasing Y: Apparent height = actual height x cos (viewing angle).

Solving for Y

1. Viewed from below and sitting on a slope, the Y—without some trigonometric help—would have appeared scrunched to viewers in the valley.

2. The surveyors did the math and laid out an elongated Y that puzzled the original builders and still surprises Y hikers.

3. The Y is best viewed from the Provo City Library—the historic site of BYU’s lower campus, where the surveying team did its work.

Fire on the Mountain

For more than 90 years students have ascended the mountainside to light the Y for Homecoming, graduation, and other notable occasions. Their method has evolved over the decades:

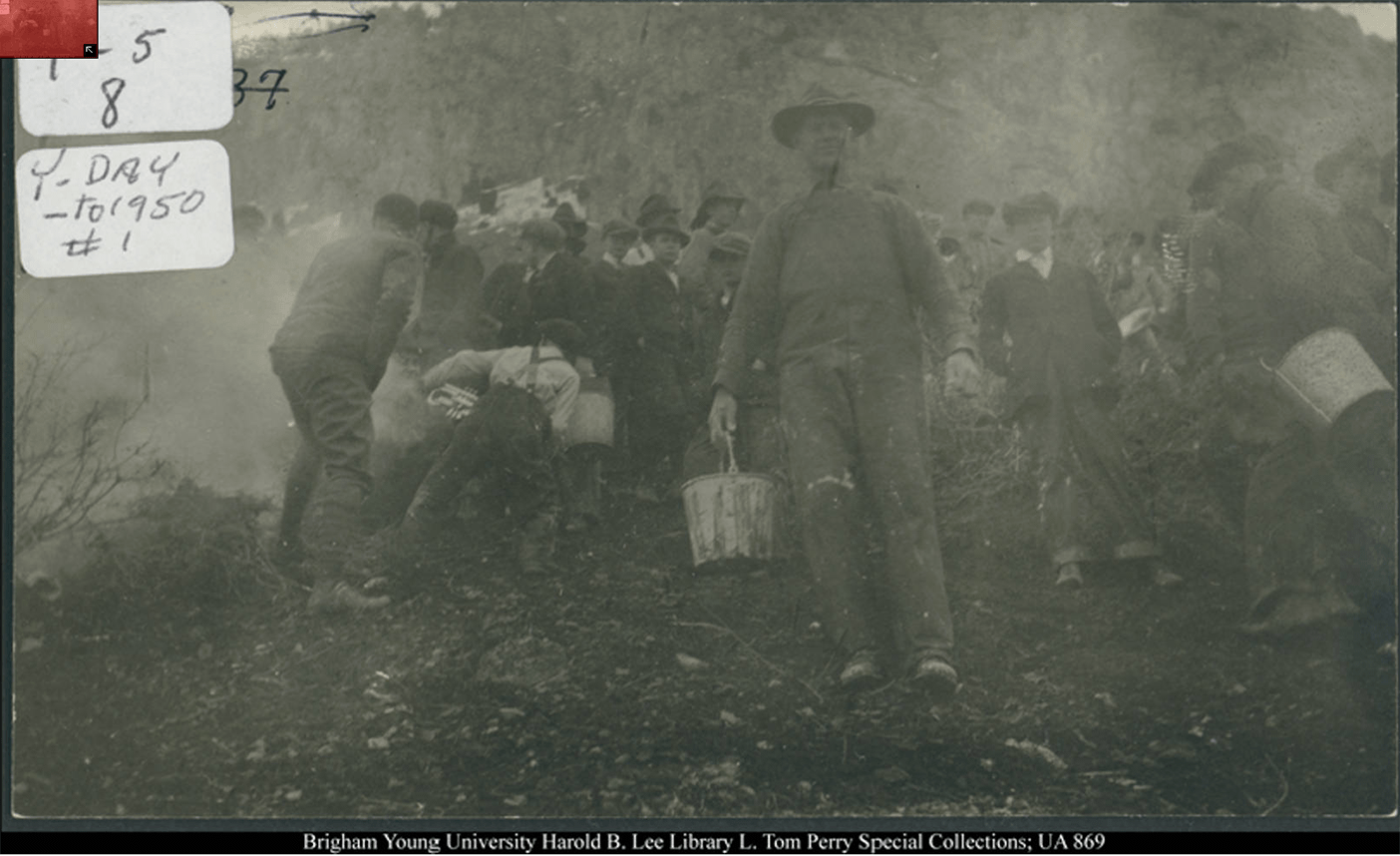

Balls of Fire

Beginning in 1924 students would soak mattress batting in spent automobile oil, then form it into softball-sized balls placed every foot around the Y. To help light them, students would first press a thumb into the balls and fill the indentation with gasoline.

Light Bulbs

Due to the hazard of open fires on the mountainside, BYU transitioned to electric lighting in 1985, using a generator and 14 strands of 25-watt bulbs.

Embedded Lights

With its 2016 upgrade, the Y now has 183 embedded LED lights rimming its perimeter. A conduit line makes it possible to switch on the lights from the electrical shop on campus below.

In an Alternate Universe

If preliminary plans had gone through, all three of the university’s initials would have adorned the mountain, not just the Y. And that would have led to some likely consequences, at least in terms of nomenclature:

There wouldn’t have been Y Days, for one. Would Wymount Terrace have been dubbed Bee-wy-yoomount Terrace? “Lighting the BYU” just doesn’t have the same ring to it. And worst of all, there would have been no Y Sparkle.

And what of the university’s nickname? The BY? Just the B? If you go there—and add in the region’s love for the beehive symbol—how tempting would it have been to brand the athletics teams as the BYU Bees? “Rise all loyal bum-ble-bees, and turn your stinger to the foe . . .”

But thanks to a shortage of lime and energy, the student crew who built the Y in 1906 decided that one whopping letter was ambitious enough. Bullet dodged.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.