By Peter B. Gardner, ‘98, Associate Editor

By Peter B. Gardner, ‘98, Associate Editor

In his tan, starchy serviceman’s uniform and with guitar in hand, Stanley W. Bronson, ’74, was led into the Song Jook Won Orphanage on the outskirts of Seoul, Korea, for the first time in April 1967. The 80 orphan girls, ages four to 18, who were assembled to greet him were shocked at first by the American’s 6-foot-4-inch height but quickly warmed to his kind demeanor and gentle mannerisms.

Bronson, a musician from Blanding, Utah, who had recorded an album of “cowboy songs” before being drafted, had arranged with Whang Keun Ok, a local Latter-day Saint and director of the Protestant Christian orphanage, to perform for the girls. Before he could play, however, Whang announced that the girls had prepared something for him as well.

Bronson listened in amazement as the girls performed Korean folk and Christian songs. “I was blown away,” he says. “These little kids were singing in two- and three-part harmony. I thought, They sing better than I do.” One sprightly 12-year-old, who seemed to be a leader among the orphans, particularly caught his attention.

“I’ll never forget that day,” he says. “That’s the day I met Cho Yoong Jin.”

Cho Yoong Jin was born in 1954, one year after the official end of the Korean War. In the survivalist culture that followed in the wake of the fighting, Yoong Jin’s parents separated and left their 18-month-old daughter to be reared by her grandmother.

Impoverished, Yoong Jin and her grandmother lived in a remote village in a thatched-roof cottage and had to be resourceful. Since they could rarely afford rice, Yoong Jin caught grasshoppers and gathered edible herbs, roots, and berries to eat. Other food was scarce and treasured. For one memorable birthday Yoong Jin’s grandmother gave her an egg, the only egg she ate that year.

Despite her poverty, Yoong Jin’s grandmother was highly educated and had been a member of the aristocracy before the war. After losing her home and much of her family, one of her few remaining possessions was a tattered old book, from which she taught her granddaughter.

“My grandmother had everything to do with my desire for an education,” recalls Yoong Jin, now Jini L. Roby, ’77, an assistant professor of social work at BYU. “She was always saying that to be uneducated would be undeserving of our heritage and that education was the way out of our current family poverty.” Yoong Jin clung to this promise of liberation, entering elementary school a year early and eventually winning an academic scholarship to a prestigious junior high school in Seoul.

Her aging grandmother, however, could not make the move. Instead, she entered a Buddhist monastery, where she spent her remaining years. At age 11 Yoong Jin entered the Song Jook Won Orphanage in Seoul and enrolled in junior high school.

Front-Runner in Everything

“In Korea children without families are the lowest on the scale because everything is tied to family,” says Bronson. So when he told them he wanted to help them record an album, the girls couldn’t believe it.

Yet, after several months of practicing, the Song Jook Won Children’s Choir recorded its album and became a national phenomenon, even exceeding Bronson’s optimistic expectations. “They went from orphan status to instant celebrity,” he recalls.

The choir, which they would later name the Tender Apples, toured U.S. Army bases, was featured on national television several times, and had appearances with broadcasting personality Art Linkletter and comedian Bob Hope. Yoong Jin, who was learning English in school, was the choir’s spokesperson in front of audiences and cameras for all its appearances. “She was the front-runner in everything,” Bronson says. “She was a charming little girl.”

As the Christmas of 1967 approached, Bronson wrote to families in Blanding, encouraging them to send winter coats to supplement the girls’ meager wardrobes. The Bart and Venice Lyman family responded, sending Yoong Jin a new coat. Using a dictionary, she wrote back in rudimentary English, “Thank you for present.” This reply marked the beginnings of both a steady correspondence and major changes in Yoong Jin’s life.

“One day Stan wrote us a little note,” Venice Lyman recalls. “He said, ‘If you want to adopt this girl, you’d better start adoption papers.’ We had never thought about adopting her. We already had a family of seven children. But we thought about it for a while, and then we decided that maybe we should.”

During the complex and agonizingly slow adoption process, Yoong Jin discovered that Bronson, Whang, and the Lymans were all members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Although the Lymans assured her they would love her whatever her religion, her experiences with these people led her to receive the local missionaries. She eventually decided to join the Church, but she wanted to wait until she was adopted so her new father could baptize her. She also decided to change her name to something more American. Friends called her Yoong Jini, and Stan suggested that Jini would make a beautiful name.

More than a year after the Lymans had offered to adopt Yoong Jin, the 14-year-old finally boarded a plane for America. “We had many disappointments and many discouraging experiences, but finally she came,” her mother remembers.

Wanting to give her an American experience, one of the first things the family did after picking up Jini at the airport was visit a nearby fast-food restaurant and order a root beer. She was repulsed by the taste.

“I didn’t really care for the food all that much,” Jini recalls of her early experiences in America. “But I was just in heaven, because I was in a family, and I had a mother and a father and people who were there for me everyday. All the little details didn’t matter.”

Although American beverages didn’t sit especially well with Jini, most everything else did. She was amazed at the contrast between the urban congestion and density of Seoul and the broad skies and red rock of rural southeastern Utah.

In her memories, those first days were like a dream. “In Korea there wasn’t an organized social life, many fun things to do, or much adult attention. But when I got here, I always had adult attention and was being driven to activities and parties. I found it rather easy to adjust to that,” she says with a smile. “I didn’t have any trouble at all.”

In her new environment, Jini not only didn’t have trouble, she excelled.

“She came determined to learn,” says Lyman. “She’d stay up in her room sometimes until two or three in the morning, comparing words in her dictionaries and learning.”

Jini’s rigorous training in Korea and her natural tenacity prepared her well for school. “Once I knew what the words were, I thought, I know this stuff,” she recalls. “The content material was so easy that I literally didn’t have to study for about three years—except for American History; I had to pay attention to that.”

Her mother tells of her determination to always do her best. “She got a job in a fast-food place during high school. It closed at about nine, but then they had to clean up. But when Jini cleans up, she cleans up,” Lyman says. “It would take an hour and a half for her get home. I’d say, ‘You don’t have to do it that good. Nobody else does.’ Jini would say, ‘I do. I’m the one who knows what I’ve done.’ That’s the way she is with everything.”

The Tender Apples, the Song Jook Won Orphanage choir, appears on the Art Linkletter Show in 1968. After Stan Bronson (center, with guitar) helped the choir record an album, the group became a national phenomenon in Korea.

Jini says her parents opened a world of opportunity to her. During high school she took piano lessons, joined school singing and dancing groups, and took advantage of every chance to learn and grow. “We gave her all the opportunities we could. Even if we hadn’t, she would have gotten them somehow, in some way,” says Lyman. “There was no stopping Jini. She was off and running and has been to this very day.”

The Road to Scholarship

Thirty-three years after arriving in the United States, Jini Roby is now an internationally respected scholar on adoption law and policy, a well-known advocate for neglected and abused children in Utah, and an influential member of the Korean American Society of Utah. In 2000 she received the Overseas Korean Leadership Award from the Korean government, and in 2001 she received the Utah Women’s Achievement Award.

Her serendipitous road to these achievements includes a wide swath of family, volunteer, and work experiences, all of which she met with the dogged determination that has become her trademark.

W. Eugene Gibbons, a mentor of Roby and a former administrator of the social work program, says she was a “professor’s dream” as an undergraduate. “She was totally self-motivated and self- disciplined. It was all I could do to stay ahead of her,” he says. “To be mediocre was to be a failure in her mind.” Roby describes Gibbons as a second father to her. “He took me under his wing. Twenty-six years later he is still my mentor.”

Amid her studying, Jini met and married Carlos Y. “C.Y.” Roby, ’77. When she graduated, she worked for several years as a social worker while he worked toward a doctoral degree. C.Y. has repeatedly returned the favor, says Jini, supporting her in many activities. “He is really rare,” she says. “To him, my project is his project.”

Yoong Jin (with Bronson, at right) meets Elder Gordon B. Hinkley in the spring of 1968. Bronson created many opportunities for Yoong Jun, including her eventual adoption by the Lyman family of Blanding, Utah, where Bronson was from.

When Jini became a mother, she met those responsibilities with the same determination. “In terms of being a housewife and a mom, I just jumped in. I really devoted my energy to that,” she says.

“She always says, ‘Family first!’—probably because she grew up partially without one,” her oldest daughter, Micia, ’02, says. Despite all her mother has accomplished, Micia says their family has always remained her mother’s top priority.

When Gibbons encouraged Roby to return for master’s degrees in social work and marriage and family therapy, she agreed only after a special program was devised for her that would not interfere with her family. She received both degrees in 1984.

Adopted Specialty

After C.Y., who had been adopted at birth, and Jini decided to marry in 1974, they went to a park and tape- recorded a message to their future children about their hopes for their family. “We talked at that time about wanting to adopt kids,” he says.

They would eventually adopt two daughters, both of Korean birth. Until they had their third daughter, their biological child, C.Y. would joke that adoption was hereditary in their family.

With the integral role adoption has played in Roby’s life, it has been natural for her to seek out ways to serve adoptive parents and children in her professional and volunteer activities. In addition to working as an adoption specialist for the World Association of Children and Adoptive Parents for several years, she was a member of the Utah Adoption Council for seven years, serving as president in 1993. She also went to the Marshall Islands in 2001 to help draft the country’s adoption law and perform research with her students.

Having been adopted from another country and culture, Roby understands the difficulties of dual-culturedness faced by some adopted children. Many international adoptees never learn about their heritage because they are adopted as infants or because they are raised in an orphanage where traditions are not observed. Those who are exposed to both cultures often struggle to maintain and find value in their former culture as they are immersed in a new one.

“My earliest recollections are of my grandmother teaching me about Korean history and helping me develop a love of Korea,” says Roby. To provide a similar opportunity for other young adopted Korean Americans, for five years Roby directed Korean Heritage Camps. One week each year children from all over the United States come to Utah, where Roby and others teach them Korean history, language, music, cooking, and current events.

“It makes them proud of their heritage, rather than feeling like it is something that makes them weird,” says C.Y. “They start to fall in love with being different.” All of the Roby children have attended the camps, and the two oldest daughters now volunteer as counselors.

Weaving Safety Nets The umbrella of Roby’s influence covers more than just adoption issues. Since 1987 she has been a member of Results, an organization that lobbies for political intervention to promote child survival, basic education, and self-sufficiency in third-world countries. In 1993 she cofounded a chapter of Results in Provo. She has also done research on such issues as elder abuse and domestic violence.

The umbrella of Roby’s influence covers more than just adoption issues. Since 1987 she has been a member of Results, an organization that lobbies for political intervention to promote child survival, basic education, and self-sufficiency in third-world countries. In 1993 she cofounded a chapter of Results in Provo. She has also done research on such issues as elder abuse and domestic violence.

“She just can’t stand to see suffering in the world,” C.Y. says of his wife’s interest in social work. “She can’t stand to see people who are not able to fulfill their potential.”

The experience that set Roby solidly in the field of social work was ironically also one that nearly persuaded her to leave it. To help put her husband through graduate school, Roby worked as a substance abuse program specialist at the Utah State Prison. As she counseled men being held in medium security, she realized that many of the inmates were fundamentally good people whose troubled childhoods and bad decisions had led them to crime. The discouraging and often overwhelming work caused her to reexamine socially accepted conceptions about crime. She discovered that almost all the criminals she counseled had been abused as children and had turned to substance abuse as a coping method, and most of them were under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time they committed their crimes. “It’s not to say they didn’t have a choice,” Roby says. But she came to recognize the vital importance of family life and early intervention in helping children develop into strong adults.

“That prison experience always guides me,” Roby says. “I believe in creating a safety net for those who are vulnerable, for those who are falling through the cracks.”

She sees dedicated parental guidance as the principle material of this safety net. “Children need to have at least one adult whom they can come to trust, who will always be there, and who will devote his or her life to that child.”

Thus in her work she views adoption as a way to help vulnerable children find security in a loving home. “It’s about finding a good home for children who are at risk of being abandoned or neglected or who have been through a significant amount of neglect.”

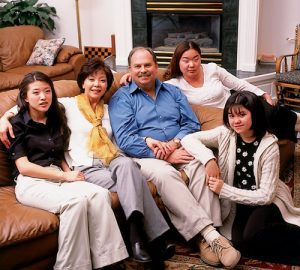

For several years Roby’s husband, C.Y. (center), would joke that adoption was hereditary in their family. Both Jini and C.Y. were adopted as children, and they adopted Micia (left) and Mikkel (second from right) before Jini gave birth to Marika (right). Adoption has been a focus of Roby’s volunteer and professional activities; she has also worked with and studied child abuse, elder abuse, and domestic violence.

In 1984 Roby founded the Utah Valley Family Support Center (now the Family Support and Treatment Center) to shelter children at risk of abuse or neglect and to educate families to avoid further risk for children. She later worked as interim director of Provo’s Center for Women and Children in Crisis.

When Roby realized that many of the problems facing such children lie at the policy level, she returned to BYU and received a law degree in 1990. She later worked in private practice with a specialization in adoption law and child advocacy. From there she went on to work as a guardian ad litem, a court-appointed counsel representing abused and neglected children. “I really loved it because it helped me to put all my education to work,” she says.

In 1998 Gibbons encouraged Roby to apply for a faculty position at BYU. Drawing on her varied background, she now teaches courses on social welfare policy, social work and family law, and international child welfare. “I really love teaching at a university, not only for the teaching itself but also because I’m learning so much. I probably learn more than 10 times what I teach.” And she hopes the lessons she is learning will make her a more capable tool for allaying suffering in the world.

Adopting the World

To hear Roby speak of her accomplishments in life, it all comes off as rather unremarkable. She sees herself as “an ordinary person who has been loved a lot and given great opportunities.” She attributes her successes to the influence of those “who had faith in my future,” she says. She stresses the impact of her adoptive parents and C.Y., as well as early benefactors like Whang and Bronson, both of whom have become lifelong friends and mentors.

Such gratitude is characteristic of the way she views her life, even the difficult episodes. “Sometimes I think, How can she not be bitter or mad?” Micia says. “It’s almost like she’s glad for everything she’s gone through.”

“Jini would find a way to be happy in any circumstance. She makes the most out of life,” says Bronson, who named one of his daughters Jini to inspire her to become like her namesake. “She would get in and be a bright spot no matter where she was.”

C.Y. says his wife’s early hardships have given her an understanding of the suffering and poverty that exist in the world and a sense of kinship with her fellow man, especially with those in need. “Jini believes that her family is everyone,” he says. “She sees everyone as her brothers and sisters, and she feels a real commitment to do what she can.”