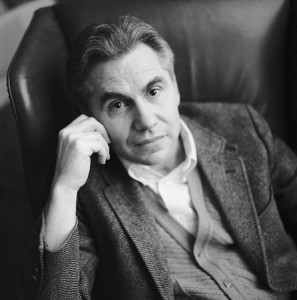

Dennis Packard is combining philosophy literary theory, and filmmaking to teach students to be generous storytellers.

By Todd R. Condie, ’03

PHILOSOPHY

A BYU professor is teaching students to create stories for novels and films after the pattern of the scriptures.

RUBEN, on his knees, reached for the soiled white sheet on the ground. Just as he gripped it, an EMT took his hand and moved it away. ‘C’mon, buddy. Ain’t gonna do no good now.'”

In 1999 Gordon D. Laws, ’00, penned those lines and the 114 pages that follow them in the novel My People. Though an atypical opening to a philosophy class writing assignment, it was exactly what his professor was looking for. At the time, Dennis J. Packard, ’02, was teaching an innovative course on the philosophy of literature; Laws was one of his top students. Packard, Laws, and the rest of the class were experimenting with an approach to literature that combines philosophical insights with gospel principles.

“At family reunions my aunts and uncles used to sit around telling stories while we were eating,” says Packard. “As a people, we Mormons have the storytelling impulse within us.”

Packard’s goal is to draw that storytelling impulse out of his students to produce novels and films that communicate morally.

Generous Storytelling

The roots of the Mormon storytelling tradition, Packard says, are found in scripture. “Understanding how scripture works is the key to our education. Biblical stories aren’t primitive; their moral sensibilities are higher than those of the best of our writers.”

In his classes, Packard and his students analyze scriptural stories, break down their narrative form, and apply similar elements to their own stories. A developed understanding of this sacred form of storytelling, Packard believes, allows his students to deal with worldly subjects in a distinctively spiritual manner. My People, for example, maintains a strong foothold in faith as it follows one young man’s conversion to the gospel against a backdrop of gang violence in the Hispanic neighborhoods of East Los Angeles. In writing My People Laws employed Packard’s storytelling philosophy, which Packard centers on what he terms generosity.

“Generosity is the term that the philosopher Sartre used; it’s a very good term with religious roots,” Packard says. Simply put, generosity refers to an open attitude toward one’s surroundings—an attitude of willing malleability. A generous person does not approach the world with the intent to mold it to his predetermined ideas but is instead receptive to all the positive influences surrounding him. From a synthesis of these influences, he forms his own actions and presence in the world. Packard compares the idea to that of tenderheartedness as found in the Book of Mormon. Being tenderhearted, or generous, entails spiritual responsiveness, willingness to be influenced by the Spirit of God, wherever it might originate.

“Something satanic, like pornography, will try to captivate the attention in such a way that there is no free response,” says Packard. “Good art is similar to scripture in that it invites us to consider and then draws us out to openly respond. Because the generosity of the artist evokes the generosity of the audience, a generous writer can’t manipulate his readers by determining what they should feel. He presents the material in an open manner so that they can respond generously to it, can complete it with their own response.”

Packard believes that this generous responsiveness leads naturally to a focus on righteousness and an accompanying grief for evil. Using such principles, he teaches would-be storytellers how to approach their stories in a way that gives them the same spiritual effectiveness as the stories they find in scripture.

Philosophy in Practice

Packard approaches his life and his scholarship the same way he approaches stories. A generous approach to knowledge disregards boundaries that are often placed on truth. Therefore, he tries to be openly receptive to the variety of sources that might enlighten his work. Since arriving at BYU from Stanford in 1974, where he earned a PhD in philosophy, he has team taught and published articles with electrical engineers and economists, with physicists and Shakespeare scholars.

“Huge splits between disciplines are old-fashioned,” Packard says. “Every discipline has gospel truths that we need to seek out—truths that are relevant to our salvation. Even philosophy. Dante described philosophers as sitting on the rim of Hell, discussing things, but philosophy is at its best when it is relevant to people’s lives.”

“Dennis is able to incorporate gospel principles into all of his work,” says Heywood Bagley, ’01, a former student of Packard’s who has returned to serve as a mentor for actors in the winter 2003 course. “He isn’t satisfied with developing new theories on how to do things; he’s excited about implementing them immediately.”

This approach is evident in Packard’s philosophy of literature classes, where writers and philosophy students team up with actors and directors, with sociologists, artists, and composers. Together, they develop an ethical foundation of generosity that is intended to permeate all of their disciplines.

In spring 2002, culminating 10 years of work, Packard was awarded a second PhD, this one from the Department of Theatre and Media Arts after presenting a dissertation on the film novel. Film novels are hybrids of traditional novels and screenplays. Packard believes film novels can precede great films—what filmmakers hope will work well on the screen should first work well on the page. He cites such examples as Of Mice and Men, The Maltese Falcon, and The Misfits. True to form, Packard’s dissertation was another attempt at pragmatic philosophy; it was, as he calls it, a poetics of the film novel.

“A poetics seeks to explain what a type of literature consists of, what the audience reaction should be to that type of writing, and what can be used to invite that reaction,” says Packard. “The purpose of a film novel, as I explain it, is to engage a generous interpretive response. How do you write film novels to invite that response? How do you film them to do that?”

The method Packard developed to elicit this response involves a tenderhearted approach to creating characters. He encourages student writers to refrain from manipulating their fictional characters to behave in certain ways. Instead, writers should respond naturally to their characters as they emerge. As a result, characters won’t force situations to a desired end but will respond generously to each other and to conflicts. The final result, Packard hopes, is that the audience will also react to the story generously, allowing themselves to be naturally moved by characters and affected by resolutions.

Packard’s unorthodox classes bring together student philosophers, writers, actors, directors, sociologists , artists, and composers.

Since Packard developed the predecessor course several years ago with David T. Warner, ’93, now director over music and performing arts at the Conference Center of the Church of Jesus Christ, his ambitions have expanded. The course has been divided into two halves taught in succeeding semesters. The first half, team taught with Terrance D. Olson, ’69, a professor of family life, uses an altered form of Packard’s dissertation as a textbook—a how-to of sorts in the creation of visually and spiritually centered stories. The second semester’s course, team taught with Charles D. Cranney, ’80, associate director of BYU Publications and Graphics, focuses on performing and producing those same stories in various media.

A Righteous Ambition

Published by BYU in 2001 with Novels for the Next Great Films on the spine, My People is intended to be the first of a series of film novels. Three other novels are currently in draft stages. These efforts have been incorporated under the name Lifesong, a multifaceted mentoring project meant to help students create stories using the principles of generosity they find in their studies of philosophical and scriptural texts.

Packard hopes to have success similar to that of his earlier forays into media production. The television specials Thanksgiving of American Folk Hymns and Songs of Praise and Remembrance, for which Packard was producer, featured BYU‘s choirs and orchestra, won numerous awards, and were shown on hundreds of PBS stations across the country. Packard sought to apply a philosophy of generosity to every aspect of the specials.

“We taught students to be responsive to music that mattered,” he says. “We explained to the cameramen and crew that what they would be seeing was like testimony bearing and should be treated as reverentially.

“People wrote us and said, ‘If there are 400 students like that in the world, then we feel a whole lot better about things.’ Someone said, ‘We saw the face of Jesus on them.’ That’s because the students were being tenderhearted.”

It’s an effect that Packard hopes to replicate in other media through Lifesong. He intends his class’s work with film novels to be a direct transition into something greater—BYU‘s first theatrically released, student-made film.

“This is an innovative way of putting students in an extreme mentoring environment,” says Cranney. “They get equal billing with professionals, but the quality is kept high by including industry mentors.”

Packard hopes to lead a legion of “tenderhearted” students trained both in technical skills and in the philosophical ideals needed to wield them wisely.

And that list of industry mentors is growing. Lifesong’s board of directors already includes some of the most prominent names in the Mormon film industry—people like Kieth W. Merrill, ’67, ofIMAX, Testaments, and Legacy fame; Sterling G. Van Wagenen, ’72, producer of the Academy Award-winning Trip to Bountiful; and Dean C. Hale, ’90, of Excel, distributor of God’s Army, The Other Side of Heaven, and Charly.

When filming for the feature-length motion picture of My People begins summer 2004, Packard and his fellow professors hope to be at the head of a legion of tenderhearted students trained both in technical skills and in the philosophical ideals needed to wield them wisely. While preparations for the filming and funding of My People continue, the second film novel in the series, Creekwater Bends, by Nathan K. Chai, ’02, should be ready for publication by summer 2003. And Packard hopes that the cycle won’t stop there. Profits from that film will be recycled to finance future films emerging from the book series.

“We, as a people, can’t simply be negative about the entertainment industry,” Packard says. “We have to be enthusiastic about the very finest stories and films; we have to study them and learn from them and learn to create them. We want the world to experience the goodness of God as it exhibits itself, not only from the Spirit itself, but from the words of a child, the performance of an actor, the movement of a cameraman.”

Todd Condie, a former BYU Magazine intern, is currently an intern for KUER radio.

For Lifesong stories, novels, films, commentary, courses, and information, see lifesong.byu.edu. Sign up for MyBYU News (mynews.byu.edu), to receive regular Lifesong updates.