BYU’s Larsen Yellowstone Collection reveals the colorful history of the world’s first national park.

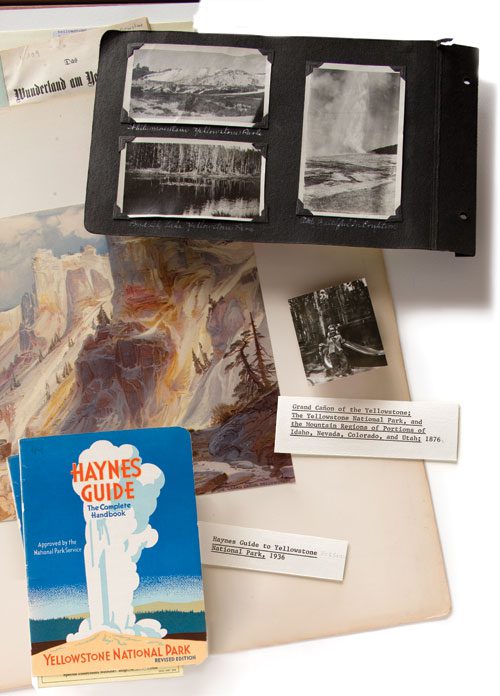

(Above) Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone is one of 15 chromolithographs in Louis Prang’s portfolio The Yellowstone National Park, and the Mountain Regions of Portions of Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah. Appraised at $350,000, the portfolio is the most valuable piece in BYU’s A. Dean Larsen Yellowstone Collection. (Below) This 1936 copy is similar, if not an exact match, to the Haynes Guide Dean Larsen purchased at age 10. It was the first piece of Yellowstone memorabilia the BYU librarian ever owned.

BYU’s Larsen Yellowstone Collection reveals the colorful history of the world’s first national park.

Before the heat of the summer of 1940 set in, and before the rationing and tight living the next year’s entrance to the war would bring, Ariel and Vera Larsen piled their children into a 1936 Packard and drove to Yellowstone National Park for the opening of fishing season. Fishing Bridge was only three years old then, and from there the Larsens cast their lines into the Yellowstone River, hoping to pull up some of its famed cutthroat trout.

Sometime during the days of fishing, hiking, and geyser watching, 10-year-old A. Dean Larsen (BA ’54) set down his fishing rod and wandered into a souvenir shop near Fishing Bridge. Sneaker-shod and overalled, he sauntered past the rows of Old Faithful key chains, collectible postcards, and other assorted kitsch and stopped in front of a copy of Haynes Guide to Yellowstone National Park.

The guidebook, with its bright, blue-and-yellow cover depicting a stylized geyser, held his attention. Dean pulled a few coins from his pocket, paid the attendant, and walked back into the sunshine clutching the first piece of what would become one of the finest collections of Yellowstone materials in the world. “From the first time he visited the park, Dean just immediately became interested in pamphlets and guides and maps of Yellowstone,” says his wife, Jean Maycock Larsen (BS ’53).

When Dean married Jean in 1958, they began a 40-year tradition of visiting Yellowstone once or twice every year. Throughout those years the Larsens added to their collection of Yellowstone materials, aided by connections and friends Dean made as the director of collections development at the Harold B. Lee Library.

By the time they donated their collection to the L. Tom Perry Special Collections in 2000, it comprised roughly 2,000 items—items as varied as “do not feed the bears” flyers, firsthand accounts of trips to the park, volumes of academic research on Yellowstone’s bears and wolves, and colorful 1880s railroad circulars advertising vacation packages. The Larsen Yellowstone Collection substantially increased in size in 2006, when Ron and Jane Lerner, friends of the Larsens, donated their equally sizeable and valuable 800-plus piece collection of Yellowstone materials.

“Having that kind of a collection at BYU … will draw people to BYU to study about a very famous place in the history of the American West,” says Fred R. Gowans (BS ’60), emeritus professor of history. Lee Whittlesey, official historian for Yellowstone National Park, ranks the Larsen Yellowstone Collection among the top five best collections of Yellowstone materials anywhere in the world. “It is wonderful,” he says. “There are some really rare individual items, where rare books are concerned.”

A few other libraries—Yale’s Beinecke Library, notably—have admirable Yellowstone collections made up almost exclusively of rare, expensive items. But according to Russell C. Taylor (BA ’70), who cocurates the Larsen Collection with Larry W. Draper (MLS ’78), the Larsen Collection is remarkable in part because it records an experience familiar to so many American families. “We have an everyman’s library of Yellowstone Park,” Taylor says. “It’s the sort of thing you would have found in the store in West Yellowstone.”

Exploring Wonderland

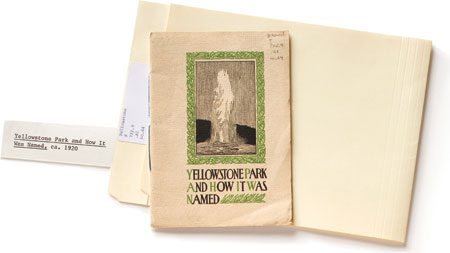

The Yellowstone Collection’s many pieces of ephemera – items such as pamphlets, maps, booklets, and postcards originally meant to be discarded – are now collectibles that provide a window to the park’s history.

Reliable information about the Yellowstone area was scarce in the 19th century. Trappers and explorers reported, as cited in numerous Yellowstone histories, craters that “issued blue flames and molten brimstone” and springs “so hot that meat is readily cooked in them.” With a tone of awe, most people simply called the place Wonderland.

In 1871 the government commissioned renowned surgeon-turned-geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden to survey the area, collect geological samples, and separate truth from fiction. Hayden’s expedition included photographer William Henry Jackson and painter Thomas Moran, a late and somewhat unlikely addition to the group. Their ostensible purpose was to provide artistic proof that this Wonderland lived up to its name. Hayden, however, had a slightly different plan for his guest artists. He wanted them to help set the stage for one of history’s greatest acts of conservation.

For months, Moran sketched and painted, Jackson labored over his heavy photographic panes, and Hayden’s team took meticulous notes. Jackson’s stunning photos of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone—several of which reside in BYU collections, along with much of his other work—present its grandeur and jutting angularity with scientific exactness. But as Hayden later wrote, a black-and-white picture of Yellowstone “is likeHamlet with the part of Hamlet omitted.” Moran’s paintings supply the missing link—color. His brushstrokes contrast the blue-green of the river with the stunning mineral hues of the canyon walls—chalk white melting into terra-cotta, pushed up against rust and burnt brown.

When the party returned east, Hayden submitted his report and began lobbying Congress to set aside more than 2 million acres of land as the world’s first national park. According to many accounts, the success of Hayden’s efforts leaned heavily on Jackson’s photographs and Moran’s art.

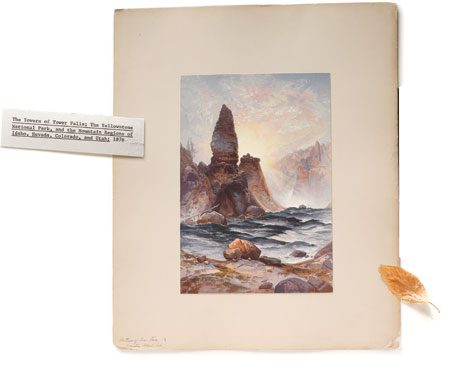

The Towers of Tower Falls, like all of the chromolithographs in the Prang portfolio, is a reproduction of a Thomas Moran painting. While Moran originals remained the province of the wealthy, Prang’s chromolithographs made the works of Moran and other artists available to a broader audience. To Prang, chromolithography was the democratization of art.

After many months of negotiations, Yellowstone National Park was born on March 1, 1872. The legislation that created the park, in truly democratic fashion, stipulated that the land be set apart “for the benefit and enjoyment of the people.”

Riding on the coattails of the national excitement over Yellowstone, Bostonian Louis Prang commissioned Moran to paint a series of pictures from his time in the West, with the intention of creating a portfolio of chromolithographs—or color reproductions—from the paintings. Some critics alleged that chromolithographs were cheap imitations, but Prang wanted to offer everyday Americans access to affordable fine art, and reproducing the work of a respected artist like Moran lent weight to his cause.

Published four years after Yellowstone National Park was established, the Prang portfolio—officially titled The Yellowstone National Park, and the Mountain Regions of Portions of Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, and Utah—is the centerpiece of the Larsen Collection. One thousand copies of the portfolio were produced by Prang by 1876, however only about 150 were initially sold. The other 850 copies were destroyed in an 1877 fire. BYU’s copy is one of the few that still exist in complete form. It came to the university in 2007 through the generosity of collectors Ron and Jane Lerner and donors Rex G. (’62) and Ruth Methvin Maughan (BA ’60).

The portfolio includes 15 prints (nine of which are scenes from Yellowstone), accompanied by text written by Hayden. The prints, distributed in an unbound portfolio so that they might be framed, could easily be mistaken for watercolors. Even on close examination, it is hard to believe that the delicate pinks of the mineral deposits and the vibrant cobalt of the water in “The Castle Geyser, Upper Geyser Basin” are the direct product of Prang’s lithography and not of Moran’s paintbrush. Castle Geyser, which is shaped like a miniature fortress, is surrounded by a number of hot springs and steaming pools—a blanket of vivid oranges, whites, and aquamarines. In the text that accompanied the print, Hayden aptly observed that the Castle Geyser area “must be seen to be appreciated, for even the artist’s pencil in this case falls short of nature.”

Yellowstone Ho!

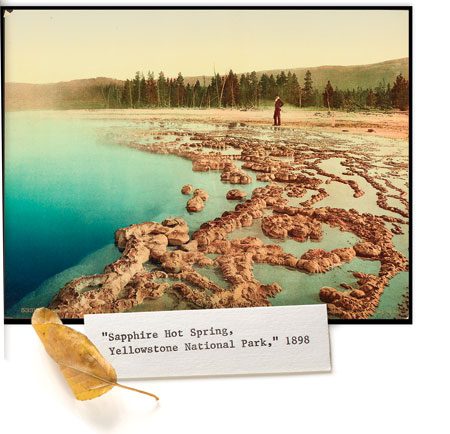

This hand-colored photograph was taken by William Henry Jackson, the first person to photograph the wonders of Yellowstone. Jackson’s photographs aided in the effort to create the world’s first national park. BYU own 56 of Jackson’s original Yellowstone images.

Spurred on by articles in popular magazines and images like the ones Prang produced, tourists began traveling to Yellowstone almost immediately after its inception. Jane Washburn and her husband were among the first generation of adventurers to experience the park after the railroad reached it.

Part of the Larsen Collection, Washburn’s 1887 book, To the Pacific and Back, is a collection of letters the Washburns sent home to their children in New York while journeying throughout the West. Washburn regales her children with stories of train crashes and lost luggage and even meeting the Mormons during a stop in Salt Lake City. That meeting must have made an impression, because the flyleaf of BYU’s copy bears a yellowing inscription: “To Mr. Heber Grant, with the compliments of the authoress. New York, May 14th, 1887.”

The highlight of the Washburns’ western trip, though, was undoubtedly their stay in Yellowstone. Speaking of Artist Point, from which perspective Moran’s The Grand Cañon of the Yellowstone is painted, Washburn says, “This afternoon we rode on horseback on the trail four and a half miles up the cañon, to see the greatest wonder in the world of its kind.… I immediately selected the point of observation in Moran’s great picture, and the coloring in that is as true to nature as art can ever be, and not at all exaggerated; but oh! How small and weak a thing a picture is to portray this marvelous work of God!”

Her referencing Moran’s painting—which in fact takes many artistic liberties—is evidence of the powerful effect the images had in creating the American West in the minds of easterners. Even those who could not come to Yellowstone in the early days felt a certain pride for this national wonder. “From very early on there was a real sense of Yellowstone as a national possession,” says Susan Sessions Rugh (BA ’74), associate professor of history, whose recent research on the history of travel and tourism in the United States drew from the Larsen Collection.

This feeling of ownership may account in part for the proliferation in the late 19th century of Yellowstone images, such as those made for then-popular devices called stereoscopes, which give photographs a three-dimensional effect. One of the many stereoscopes housed in the Larsen Collection is a device made from a dark metal, with swirled coppery accents and a worn wooden handle. Getting the scene of Yellowstone’s Grand Canyon to come into focus requires a bit of tromboning, but the moment it does—tall pines springing out from the frame, steep canyon walls stepping forward, and the powerful spray of the 308-foot-tall Lower Falls receding into the distance—it’s easy to see how people in the East felt that owning a stereoscope was the next best thing to being there.

Paving a Way through the Park

The year 1917 brought an important change to Yellowstone: cars. And with the cars came many more visitors. The average park attendance per year in the 1920s was more than triple what it had been in the previous decade, because cars made the trip more affordable for people of ordinary means, like Jean Larsen’s parents, who took their honeymoon to Yellowstone in 1923. A government pamphlet from the collection that was issued when the cars were first allowed in reinforces the sense of national possession: “This Park is yours,” it said. “You, its owners, are free to see it and enjoy it in your own way.”

During the ’20s, a culture of traditions and commerce grew up around the park and the large staff who began working there each summer to accommodate the boom in tourism. The Larsen Collection contains various souvenir books that were sold in the park—both professional items produced by official park photographer F. J. Haynes and scrapbook-like products that allowed travelers to insert their own photos and write down memories.

Also in the collection are songbooks from various Yellowstone camps, with ditties about campfires, mosquitoes, passing the cheer germ, and the general joys of Yellowstone. The back covers feature glossaries of Yellowstone slang. There, tourists are alternatively termed “dudes” or “sagebrushers” (depending on how they travel), dishwashers are “pearl divers,” and dating in Yellowstone is “rotten logging.”

Though laundry services were available at places like the Old Faithful Inn (courtesy of the “pillow punchers,” or lodge maids), many tourists staying in the Upper Geyser Basin during the early 20th century preferred an alternate method of keeping their personal effects clean.

John A. Ward, whose book, The Story of My Life, resides in the Larsen Collection, reports, “We went to a lake, or rather a bubbling spring, where we washed our handkerchiefs. It was called the

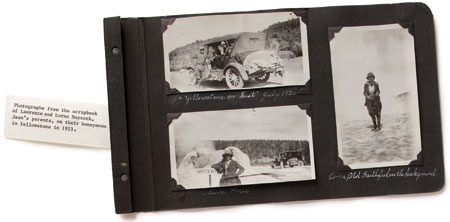

Photographs from the scrapbook of Lawrence and Lorna Maycock, Jean’s parents, on their honeymoon in Yellowstone in 1923.

‘Laundry Spring.’ We could see an opening downward, a sort of cavernous opening, the walls were coated with sulphur mingled with a green substance all flashing in the sunshine.” Unfortunately, so many enthusiastic visitors attempted to wash handkerchiefs in this spring that it was clogged in 1929, and placing anything in a thermal feature in Yellowstone was later declared illegal.

Like many travelers, Ward marveled at the clarity and vastness of Yellowstone Lake, the beauty of the Yellowstone River as it “goes purling and rippling through the valley,” and of course Old Faithful’s timeless regularity. “This old geyser,” he writes, “spouts boiling water a hundred feet high at regular intervals of one hour, never ceasing, always on the job.”

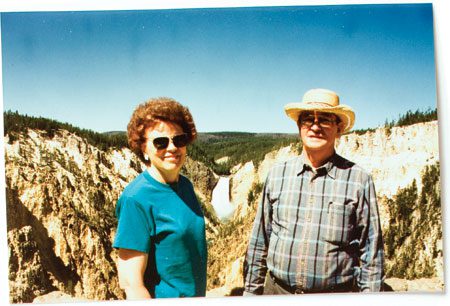

Jean and Dean Larsen visit Artist Point’s in 1988. The couple donated their personal collection of more than 2,000 Yellowstone items to BYU and established an endowment for the collection’s continued growth.

Ward summed up his overall astonishment, and that of many visitors, with this pronouncement: “We don’t have to cross the sea to behold the wonders of the world,” he writes. “I visited Yellowstone Park.”

The Preservation of a Legacy

Dean and Jean Larsen traveled all around the world together, but it was to Yellowstone they returned every year, including in 2001, the year before Dean died. “Yellowstone is home,” Jean says, simply. And Jean and curators Taylor and Draper all emphatically agree that you haven’t seen Yellowstone until you’ve seen it with Dean.

With the gift of the Larsen Yellowstone Collection, Dean and Jean Larsen have passed on their legacy of love for the park to future generations. It’s a passion shared all over the world, and one well worth being a

One of the largest and finest collections of Yellowstone materials in the world, the Larsen Collection is replete with publications describing how, and how not, to interact with the wildlife.

part of—for as Hayden wrote of Yellowstone, “all the ordinary

standards of landscape beauty fail in the presence of these marvels.”

As was intended, many of those marvels have remained largely unchanged in the 136 years since the creation of Yellowstone National Park. Going back to nature in the 21st century may mean sharing it with tens of thousands of other adventurers on any given summer day.

But on the south rim of the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, signs lead to Artist Point, which still affords Moran’s famous vista from the edge of the rugged cliffs. Travelers from around the world line a boardwalk every hour to see Old Faithful put on a show, muttering, “Come on, come on … ,” and holding cameras at the ready as the geyser’s jet starts to rise. Nearby, Castle Geyser’s sulphurous smell and brilliant hues are as strong as they ever were. Fishing is no longer allowed on Fishing Bridge, but families come anyway, leaning over the railings and watching pelicans fly and land in graceful formation on the smooth water of the Yellowstone River.

And across the river in the general store, wide-eyed children still peruse the merchandise, pull coins from pockets, hold tightly to their new treasures, and understand—perhaps for the first time—that they belong to this place, and it belongs to them.

Riley Lorimer is an editor at the Joseph Smith Papers Project. As an 8-year-old on a summer vacation in Yellowstone, she spilled milk on her shorts at dinner and left them atop the tent pole to dry overnight. The shorts froze solid.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

More info: To learn more about the A. Dean Larsen Yellowstone Collection, e-mail larry_draper@byu.edu.