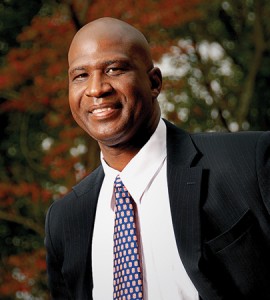

Keith Hamilton, the BYU Law School’s first black student, has written a book about the priesthood and blacks.

Keith N. Hamilton (JD ’86) believed he had reached the pinnacle of life. As a black student at North Carolina State University in 1980, he was a popular DJ doing private dances and occasional club gigs. His fraternity had a strong campus presence, and with only a couple of classes required for graduation, he anticipated a fun-filled senior year. Hamilton had no idea his life was about to change profoundly when two young men in white shirts and ties knocked on his door on a muggy afternoon.

Hamilton, seeing them sweltering in the heat, invited them in for ice water. When he learned they were missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, he was surprised, declaring he did not think Mormons were recruiting blacks. After he was advised otherwise, he said, “Well, whenever you’re in the neighborhood, stop by.”

That was all the encouragement the missionaries needed. They became frequent visitors and soon challenged Hamilton to get an answer about the gospel. His prayers led to his testimony and a changed life. In a little more than two weeks from first hearing about the Church, Hamilton was baptized.

“I found a truth that resonated and guides my life,” he says. “Yet I know my experience is unique to me. I mean, how many members of the Church . . . [grew] up in the Deep South during the Jim Crow era? My grandfather was a Southern Baptist minister. I saw the unfolding of the civil rights movement.”

Comfortable with the doctrine, Hamilton’s assimilation into the culture of the Church was more challenging. “LDS culture, like any other specific culture, has its own unique vernacular, composed of completely uncommon words: patriarchal blessings, Quorums of the Seventy, and the Relief Society. And what had I ever heard about Adam-ondi-Ahman, Deseret, and people named Amulek and Moriancumer?

“I also wondered how people would respond to me,” he says. “I wanted people to recognize that I’m a person of worth and not avoid me because my skin didn’t look like theirs or [because] I was from another part of the country.”

After graduation, Hamilton served a mission in Puerto Rico. When he returned, he entered BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School as its first black student and embarked on a career that has included serving in the military, working for the BYU Alumni Association, serving on the Utah parole board, and teaching classes at BYU’s law school.

While Hamilton says the Church’s background on blacks and the priesthood has never bothered him, a few experiences he had in the late 1980s while serving first as counselor then as bishop of the San Francisco Bay Ward motivated him to help those for whom the issue is a stumbling block. He began to research the historical relationship between blacks and the Church, and his findings became so extensive, he realized he had enough material for a book. After 20 years of research and two years of full-time writing, he finished Last Laborer: Thoughts and Reflections of a Black Mormon. The first half of the book is his autobiography, and the second half contains what Hamilton calls a “doctrimonial” text, where he shares his personal story of faith and testimony, trial and triumph.

Among the reviewers of Hamilton’s book is Edward L. Kimball, retired BYU law professor, who wrote, “Beyond telling a fascinating story of his life and conversion, Hamilton illuminates what it means to be black and Mormon. . . . This is a careful, thoughtful book.”

“I just hope people feel the song of my soul and my testimony about God’s plan,” Hamilton says.