By Jeff McClellan

For centuries, the shores of Fish Lake were a gathering place for native cultures. Among the pines and aspens, they hunted. In the hills, their children played. At the lake’s edge, they performed sacred ceremonies. Last summer, these ancient cultures crossed paths with modern peoples as Native Americans and a BYU-led team of archaeologists collaborated to uncover the history of Fish Lake. In the process, they found a connectedness, not only with the past but also with each other–and with the future.

This is sacred land. So the local Indians tell me. And, surveying the landscape from a grass-covered ridge in Fish Lake Basin, I am inclined to agree. Stretching away to the south, the long, narrow lake highlights the basin, tucked away at the top of a high-country plateau. The lake’s smooth surface reflects the aspen- and pine-covered mountains that rim the basin, and the early morning central Utah sun lights the pale green grasses on the surrounding low hills.

A hushed stillness reigns over the land. Two lonely cars sit at the base of the ridge, and the empty two-lane road winds through the hills and along the lake’s edge like a braid of long black hair slung over a soft shoulder.

The air is still. The Paiute Indians who live nearby say that in the early morning hours there is no wind, so the smoke will go straight up. It is at this time of day that they perform their burial ceremonies. One year after someone dies, the Indians burn all that the person owned–sending the belongings with the smoke and ashes straight up to the deceased.

In the calm of the early morning, I can easily picture such a sacred ceremony taking place on this ridge–called Moon Ridge–or perhaps on the next hill over, when there wasn’t a road separating the two. I can’t, however, picture these hills as a hub of activity–a Grand Central Station, a Times Square, or a Wilkinson Center. But when BYU archaeologist and associate professor of anthropology Joel C. Janetski looks at this ridge, that’s exactly what he sees: a gathering place, a crossroads.

If the barriers of time were removed, Moon Ridge would be covered with people–campers from a year ago building a fire; hunters in the 1960s loading a shotgun; Ute and Paiute children a century and a half ago playing games; their grandparents 50 years before them performing a burial ceremony or perhaps cooking a rock chuck; Fremont people building a temporary summer home on the shores of the lake nearly 1,000 years ago; and other people gathering roots and bulbs about 300 years after Christ.

Fish Lake has historically been a gathering place, an area where people come to hunt and fish, to enjoy the cool summers, to perform sacred ceremonies. The summer of 1995 proved no different than hundreds of summers before, but this time Fish Lake was the site for a gathering of a different sort. During a unique BYU archaeological dig led by Janetski, Fish Lake became a get-together for two cultures that are traditionally at odds, two cultures that sometimes seem to be separated not only by differing philosophies but also by time–the cultures of the archaeologists and of the Indians.

Conflict of Cultures

To Rick Pikyavit, a Southern Paiute, the pit of ashes Joel Janetski was excavating looked suspiciously like the pits his family used when they roasted rock chuck–yahaputs in the  Paiute tongue–during his youth. But he also thought the pit could be the remains of a burial ceremony.

Paiute tongue–during his youth. But he also thought the pit could be the remains of a burial ceremony.

“That’s one of the things that really made me get involved with the Fish Lake project,” says Rick, who had been invited by Janetski to join the BYU excavation. If the pit were the remains of a burial ceremony, he says, “that’s really spiritual and shouldn’t be bothered or tampered with at all.”

Keeping sacred burial sites untouched is one of the main concerns of Native Americans when it comes to archaeology, says Mel Brewster, a Salt Lake City-based archaeologist with the Bureau of Land Management. Brewster spent a week observing the BYU Fish Lake project last summer.

“American Indians have traditionally looked down upon the profession of archaeology because, in many ways, archaeologists mess with items of cultural patrimony–such as burials and grave goods–that no one is supposed to touch,” explains Brewster.

In the burial ceremonies of most tribes, the burial site is given to the care of the creator, he says. “Nobody ever has a right to disturb that sacred area because it belongs to God.”

In an effort to guard their burial grounds and sacred sites against archaeologists’ trowels, Native Americans pushed for legislation to provide legal protection. In 1990, Congress granted their request through the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

Although NAGPRA returned control for Native American human remains and sacred objects to the descendants of those people, the traditional rift between archaeologists and Indians goes beyond the protection of graves, says Brewster.

As both an archaeologist and a Northern Paiute Indian, Brewster sees the conflict as a lack of understanding on both sides. Among Native Americans, there is a general lack of knowledge about archaeology; that lack of knowledge leads to natural suspicion. The corollary is true for archaeologists, a large majority of whom are not American Indians. “Many times archaeologists grow up in an environment where they don’t know Native Americans, and they’ve only read about them in books,” Brewster says.

Because the two groups are so unfamiliar with each other, archaeologists sometimes unintentionally offend Indians, who sometimes, as a matter of defense, don’t give archaeologists a chance to prove themselves.

To solve the problem, Brewster says, efforts need to be made from both sides to educate each other–efforts not unlike those taken by Janetski last summer.

Seeds of Friendship

“To be honest, I didn’t really have all of this in mind,” says Janetski of the project and its inclusion of Native American consultants. “It sort of evolved.”

As part of its Passport in Time program, the U.S. Forest Service invited Janetski to Fish Lake in 1993 to survey a few archaeological sites where some 10,000-year-old projectile points had been found. When Janetski visited the sites, however, he realized that the ancient points may have been transported there by people who lived much later.

“I am interested in really late time periods–like the 14, 15, 16, and 17 hundreds a.d.,” says Janetski, director of BYU’s Museum of Peoples and Cultures. “When I saw some of these sites, I recognized that they were very late, and that’s when I got really interested.”

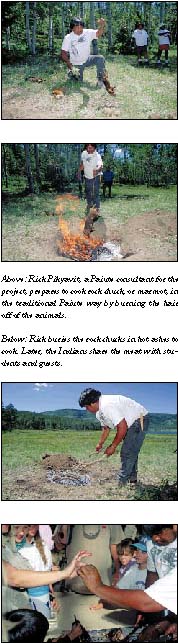

That’s also when he realized an archaeology project at Fish Lake would benefit from the memories of local Native Americans. Using a unique blend of archaeology and oral histories, Janetski and his team decided to create a film to document the human history of Fish Lake Basin. To recruit help with the oral histories, Janetski invited Rick and Rena Pikyavit, of the Kanosh Band of the Paiute Indian Tribe of Utah, to visit the Fish Lake excavation. As a former president of the Richfield, Utah, chapter of the Utah State Archaeological Society, Rena welcomed the invitation.

During Rick and Rena’s visit, in the summer of 1994, Janetski began discussing with them some of the ash pits he was finding. It was then that Rick told Janetski how his family, and more ancient Paiutes as well, would use similar pits to roast small mammals called rock chucks or marmots.

“Joel was really interested in that,” Rick recalls of the BYU archaeologist. “And I said, ‘You know what? I can shoot a couple and make the students taste it.’ Then Joel started talking about involving the Native Americans in the excavation.”

During the next year, Joel contacted the Paiute Tribe. By the time the project resumed in June 1995, Ganaver Timican and her uncle, Douglas Timican, joined the team as representatives of the Koosharem Band, the band that traditionally used Fish Lake. Together with Rick and Rena, their purpose was to consult on the archaeological dig and to help with the oral histories for the film. Moving their families up to Fish Lake, the four Native American consultants joined the group of nearly 20 students- including two non-BYU students–who would spend the summer learning the ins and outs of archaeology.

Initially, there appeared to be some uneasiness on the part of the Paiutes, Joel says.

The night before Rick and Rena first came to visit Joel at Fish Lake, Rick had a dream. “The old ones were telling him, ‘This is your blood. We don’t want them digging this up, and we don’t want them doing anything to it. Don’t bother it,’ ” Rena explains.

Troubled by his dream, Rick approached the project warily, but after that first visit, Rena says they felt good about the excavation.

Ganaver says she was also concerned at the beginning. “We didn’t know what to expect, really.”

As the project began, uneasiness lessened and excitement grew. Ganaver explains, “At first we just helped the students with what they found. And then we started getting involved with screening and digging for the artifacts, and it got more and more exciting.”

“I felt funny at first digging around and sifting through,” says Rena, “but when we started finding things–like I started finding game pieces made out of bone–I figured maybe I knew what they were: ‘Gosh they’re game pieces. These are like hand game pieces. These Indian people were playing with these just like we play with our game pieces!’ “

Discovery in the Dirt

As the Indians and the students dug side by side for seven weeks, an interesting discovery experience occurred. What may have appeared like a puzzling polished bone to a student was for Rena a game piece. The students discovered a new dimension to their work, and the Indians discovered a connectedness with their past.

“The Native Americans can tell us things we’ll never find in the dirt, and we can tell them things they’ve lost,” says Lis Nauta, one of the student crew chiefs.

In the oral histories done for the film, the archaeologists learned of traditions and stories that had been passed down from previous generations, Janetski says. Through the archaeology project and other historical means, some of those hazy memories were verified.

For Rena, the experience was one of finding an identity with the past as she dug up jewelry not unlike her own or as she found other artifacts that reminded her of her life today.

“The pottery was the most important part for me,” she says. “I could feel where they have been. I could touch what they’ve touched. I could see where they have gone by. With every piece of pottery I picked up, I looked at it, and I felt it, and I put my nails where their nail marks were. It was just like maybe I was picking it up for them and living it again for them. I felt like I was a part of what they were doing. I felt good about it. They were teaching us, and we were teaching everybody else.”

In addition to building a connectedness with the past, the project brought to the Paiutes a sense of pride for the present.

“After we went up to Fish Lake, my kids started wanting to learn how to speak Paiute,” says Ganaver.

For many Paiutes, the old ways, including their language, have been lost. Sent to White boarding schools when they were young, the grandparents of today’s Paiute children were punished for speaking their language and for practicing Indian ways. As a result, many of them forgot or were afraid to use what they had learned from their parents.

“After this project, I told my kids to be proud of who they are and not to be ashamed,” Ganaver says.

The project also gave the Paiute Tribe increased visibility and showed others that the tribe has a long history in central Utah. Like many Indian tribes, the Paiutes have suffered a troubled past and near invisibility at times. But the invisibility of the Paiutes has been more official and perhaps more brutal than most.

Through an experimental policy to integrate Native Americans into society, the government terminated federal assistance for the Utah Paiutes in 1957. Although tribal status and federal assistance were restored in 1980, the intervening 23 years took their toll. Subject to property taxes, the Paiutes lost much of their land. And denied federal health care and social services, the tribe experienced a dramatic rise in the death rate.

After restoration the situation improved, and the Paiutes were again given reservation land. But the 4,770 acres they received is much less than the more than 13,000 acres lost during termination. And, even combined with the other Paiute reservations in Utah, Arizona, and Nevada, it pales in comparison to the land the Paiutes once claimed as the Paiute Nation.

Sun Dances at Fish Lake

The Paiutes, or Nuwuvi as they call themselves, were a peaceful people who farmed, hunted, and gathered food on land stretching from the southern California deserts to northern Arizona and central Utah.

Although the Ute Indians used Fish Lake Basin before the Paiutes, when the Paiutes came, the two groups peacefully shared the land as a traditional summer retreat.

As Ralph Pikyavit, Rick’s uncle who calls himself Red Cloud, says, “It’s just an area where the Indians came up to have a good time. We came up here to do all of the spiritual things because it’s pretty high, and the Indians like to get up high to talk to the Great Spirit.”

Among the spiritual things done at Fish Lake was the sun dance, a week long ceremony of fasting and dancing in which the participants seek visions, guidance, and help for their people.

“It’s been 60 years since they had the last sun dance up here,” says Rick. “My grandfather was the last one to dance the sun dance here.”

Over the past century the Utes and Paiutes were gradually moved off the land at Fish Lake and onto ever-diminishing reservations. In recent years the government gave the Paiutes 480 acres at Fish Lake to use four weeks out of the year for ceremonial purposes, but until the summer of 1995, the tribe had not used the land. When Joel decided to take Rick up on his oVer to cook rock chuck for the students, the event soon turned into an official tribal gathering at Fish Lake.

Standing at the south end of the lake, where the Paiute ceremonial land is located, 57-year-old Red Cloud enjoys the first tribal gathering at Fish Lake in his lifetime as his nephew cooks rock chucks for a mixture of Paiutes, archaeologists, students, and reporters.

“It’s pretty country,” Red Cloud says, surveying the landscape. “I wouldn’t give it away.”

Land of Many Peoples

The Paiutes and Utes weren’t the first to recognize Fish Lake as pretty country. As Janetski and his students discovered last summer, the Fremont people spent time at Fish Lake a few hundred years before the Paiutes. And before the Fremont, there were others.

Fish Lake has been a gathering place for centuries, says Janetski. “The native peoples were up here spending the summers fishing, hunting, gathering food, and getting out of the heat of the valley just like tourists do today.”

At the BYU dig called Mickey’s Place, a low hill just north of the lake, student Lis Nauta gives one reason the researchers believe the Fremont only spent the summers at Fish Lake. Pointing out a circular structure of rocks, she explains that Fremont people usually lived in pit houses. The structure that stood here was likely a wickiup, an above-ground dwelling the Fremont would build as a temporary summer home.

The Fremont people–called Moki by the Paiutes–spent about 1,000 years in the central Utah area. Carbon dates from the Fremont occupation at Mickey’s Place indicate the site was used between about 800 and 1,100 years after Christ.

A crew of five students and one crew chief worked on the site at Mickey’s Place. Two more crews of the same size worked at the other site of the BYU dig: Moon Ridge.

“There are multiple occupations on Moon Ridge,” says Suzanne Cowen, a student from Georgetown University who joined the BYU project and worked at Moon Ridge. “It’s not like there were only people there during a certain time period. There were people camping there last year, 50 years ago, 100 years ago.”

There were also people living there nearly 2,000 years ago, says Janetski. Unlike Mickey’s Place, Moon Ridge shows evidence of several occupations in different time periods. Near the top of the ridge, the team found two circular rock formations like the one at Mickey’s Place. That occupation dated to the end of the Fremont period, about a.d. 1300. Lower on the ridge, rocks in a crude U shape characterized a site dating way back to about a.d. 300, the Late Archaic period. And right between the Fremont and the Late Archaic occupations, the students found a small site dating to about a.d. 1650, the time period archaeologists call Late Prehistoric.

Limited by time, the BYU team was only able to excavate a sample of the occupations at Moon Ridge. Janetski says the area shows evidence of repeated use with occupations on top of occupations, suggesting Moon Ridge has been used for hundreds of summers from a few centuries after Christ right up until historic times.

It was the more recent occupations that, for Janetski, were exciting. “There has been almost no archaeology done on the late sites,” he says. “Everybody likes to look at Fremont stuff and at cave sites. So the late occupations from the last 500 years–the Late Prehistoric or post Fremont time period–have largely been ignored. The archaeology we have done at those late occupations is really the first extensive work done on the Late Prehistoric.”

Through the work done in the Late Prehistoric areas, Janetski was able to get dates for pottery styles that had never been dated before. In addition, it was in those areas that the team found the most exciting artifacts, including a pendant made out of a grizzly bear tooth, some bone beads, and several large stone drills. There were also metal arrow points and glass beads, unusual finds that are indicative of post-European contact.

A turquoise bead was among the more exciting discoveries. A stone used by the Navajo Indians of the Southwest, the turquoise shows there was contact between Paiute and Navajo people hundreds of years ago. And that means, Janetski jokes, that the marriage between Rena, who is Navajo, and Rick, who is Paiute, isn’t that unusual after all.

One of the most unique things about Moon Ridge is the combination of so many time periods in one location.

“We’re in a position now where we can compare life over a fairly long time period, from about 2,000 years ago right up until the present,” Janetski says.

Since the project ended in August, the students have been enrolled in a laboratory class where they analyze the finds. With data sets from Late Archaic, Fremont, and Late Prehistoric periods, Janetski and the students can look at changes in tools, animals hunted, diet, economy, and even environment. They can also try to explain why those changes occurred.

“Archaeologically, that’s pretty exciting,” Janetski says.

And although he can now look at life over a long period, he hastens to clarify: “Life through the eyes of archaeology is pretty narrow. What we can’t get into is who got mad at whom and who married whom and that kind of stuff. But we can talk a little bit about the material side of life.”

Collaboration of Perspectives

Archaeology’s material focus opened the door to one of the greatest contributions of the Paiute consultants, says Janetski. While the archaeologists and students interpreted artifacts materialistically, the Paiutes brought a different perspective.

Saturday mornings during the project were occupied by “walk-abouts” in which the entire excavation team would visit each site and discuss what had been discovered during the week. During one walk-about, the group was talking about

the Late Archaic occupation on Moon Ridge. The occupation sits at the southern end of the ridge–a great location with a beautiful view of the lake. But, although Fremont and Late Prehistoric people lived within 50 yards of the site, there was no evidence of any lengthy or intensive use of that specific location during the almost 2,000 years after the Late Archaic people left. This was especially perplexing because the other sites on the ridge showed evidence of being used over and over. Puzzled, the crew began postulating explanations.

“We were coming up with all these sort of materialist explanations,” says Janetski, “and Rena finally said, ‘You know, I don’t think the people wanted to come here because they were afraid to disturb the spirits of the earlier people.’ “

The Native Americans often came up with human-oriented interpretations like that, Janetski says. They were more interested in the people that lived there than the artifacts they found. “That was really great because archaeology, ultimately, is supposed to be about people. It’s not supposed to be about things. The Paiutes really kept our perspective proper, correct.”

The students also came to value the Paiute input, and many commented that they couldn’t imagine doing archaeology without Native Americans.

“It has brought a real good living perspective to an old people,” says Clint Helton, who worked on the Moon Ridge site.

Another student recalls Rena telling the students, “Don’t ignore the Native Americans now, because we’re still here.”

“That really put things in perspective for me,” says Jodi Bradshaw, “because we’re studying about these ancient tribes, but if you ignore the people now, then it doesn’t mean anything to study the history.”

Giving students the rare experience of working with American Indians is part of what will heal the troubled relationship between archaeologists and Indians, says Brewster.

Janetski agrees. “The students basically grew up, you might say, doing archaeology with Indians–doing archaeology with the people whose past, in a general sense, was being explored.”

The experience of working with Native Americans was a first for Janetski. And he says it won’t be his last; this collaboration is the wave of the future for archaeology, he says.

“We hope to be doing a lot of work in partnership and in tandem with Native Americans. And their perspectives on what we’re finding are going to be just as important, if not more important, than what the archaeologists think they’re finding.”

Such a collaboration solves many problems, says Brewster, as Indians not only observe the project but are also trained in archaeology. In addition, the archaeologists learn about Native American culture and get to know real Native Americans.

The Paiutes also responded positively, says Ganaver.

“After the project I got good feedback from other people and from the band and from the tribe,” she says. “They were excited about it, and the tribal chairperson was really glad that we had done it.”

The chairperson even encouraged future collaboration on archaeology projects, she says.

Janetski and the Paiutes are already planning their next united effort. In October 1996, they and the students will present a symposium on the Fish Lake project at the Great Basin Anthropological Conference. The film created during the project will be shown at the conference, and the Paiutes, the students, and Janetski will each present their findings and their views of the project.

“We’re trying to continue to stay in touch with these people,” says Janetski, adding that it would be wrong to end contact just because the excavation is finished.

“The relationships developed were more important than whatever we found archaeologically.”

Land of Peace and Friendship

Strong relationships were developed between the Paiutes and the BYU crew during the two months they spent camping and digging in the dirt together. Those relationships are apparent near the end of the project when reporters, archaeologists, students, and Paiutes gather for the rock chuck roast on the Fish Lake tribal land.

In the morning, Rick and Joel hunt rock chucks. Later, while the animals cook in a pit of ashes, Rena, Ganaver, and a few students prepare the rest of the food. Other students and Paiutes mill about in the shade of the trees, and a few Paiute children play at the lake’s edge with a student. Meanwhile, archaeologist Joel turns taxi driver as he ferries people back and forth across the lake in a small motorboat.

Students and Indians walk in and out of a tepee, and a few people relax in a shade house constructed of logs lashed to trees and covered with leafy branches. Undisturbed by the laughter and chatter, an osprey soars low over the gathering, skimming the tops of the aspens at the edge of the lake and disappearing out of sight.

After the meal, from the shade house come the sounds of a drum beating and a woman’s voice singing a Paiute song. The song and the drum stop, and the brief quiet is followed by laughter. In the shade house, Rena, Red Cloud, and some other Indians play a traditional Paiute hand game with Joel and a few students–perhaps the same game the ancient Paiutes played with the bone game pieces found during excavation. Passing two small bones–actually carved wood–between their hands, two members of one team try to hide the bones from the other team, which must guess which hands hold the bones.

But it’s not the cowboys–or the archaeologists–against the Indians this time. Joel sits near Rena on one team, and Red Cloud is joined by a couple of students on the other. And it doesn’t matter that Joel is an archaeologist or that he and his students are white. And it doesn’t matter that Rena is really Navajo and that Rick is Paiute. As Rick says, “We’re all made from that same creator.”

Besides, this is Fish Lake, sacred land–the place where time dissolves, where the old people of many cultures dwell together, and where, in the early morning hours, the smoke goes straight up to the heavens.