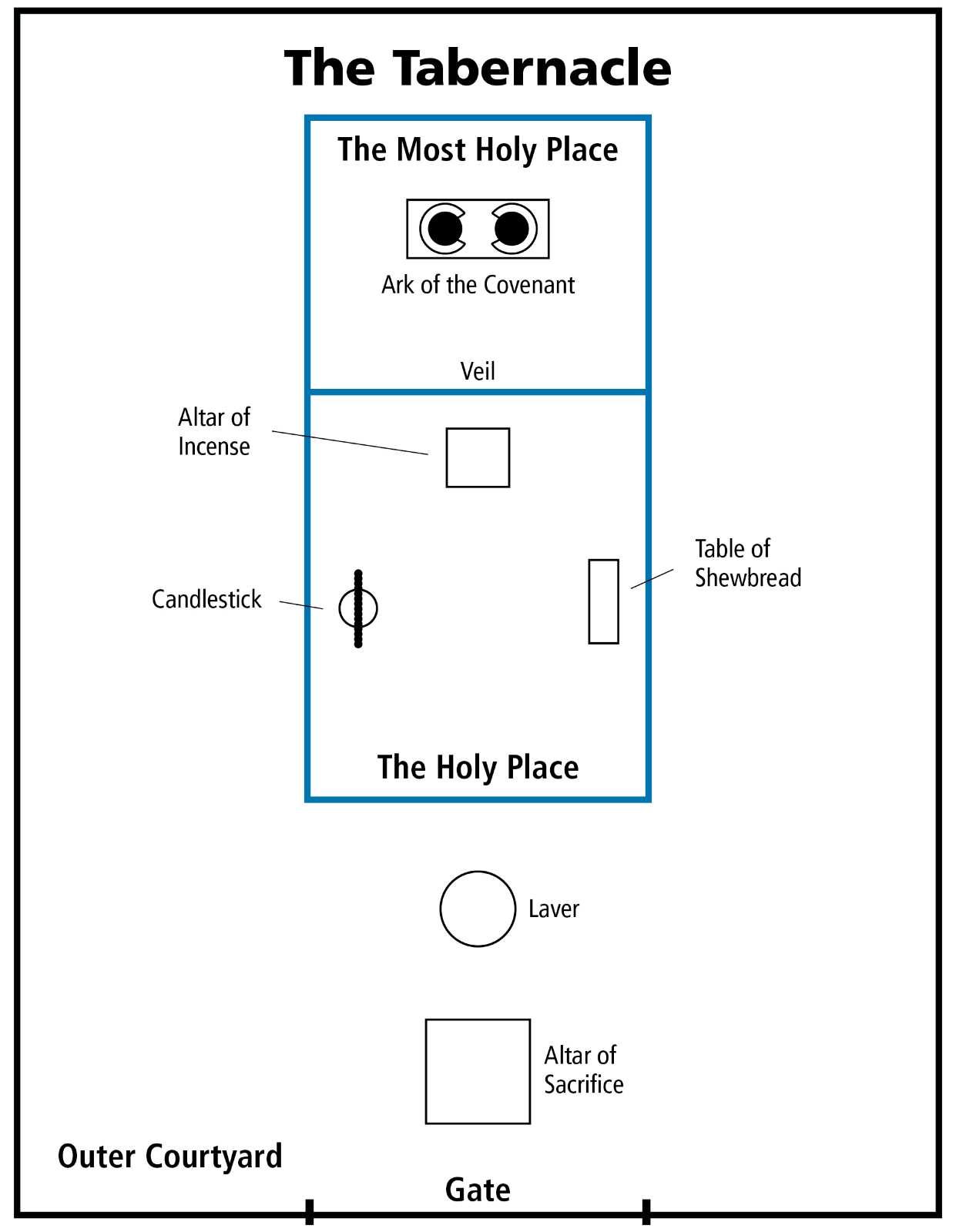

The ultimate object lesson is set up at BYU in the quad between Kimball Tower and the Joseph Smith Building (JSB) this October. It’s a life-size replica of Moses’s tabernacle, complete with an altar of sacrifice and the ark of the covenant. Through tours BYU students and community members are learning about the ancient rituals that took place in the Biblical tabernacle and how animal sacrifice, the burning of incense, and the menorah connect to modern LDS beliefs.

The replica was created by members of the Huntington Beach and Murrieta California Stakes, who tapped BYU professor of the Hebrew Bible and Dead Sea Scrolls Donald W. Parry (BA ’85, MA ’86) for guidance on constructing the tabernacle. After using the tabernacle for youth conferences and community open houses, the California stakes have loaned the tabernacle out to stakes and other groups across the country, making a stop at BYU.

Although tickets went quickly for the BYU tours, on-campus visitors can still learn about the Old Testament tabernacle through a display in the JSB lobby. The exhibition includes displays based on 3D models created by I. Daniel Smith (BS ’07, MPA ’10) and Brian Olson.

With BYU’s robust expertise in Biblical and ancient Near Eastern studies, we’ve asked Parry and several professors from the College of Religious Education to give insights on six signature elements of the tabernacle.

1. Altar of Sacrifice

Professor Parry: The law of Moses included a complex set of sacrificial offerings, which were given at the tabernacle’s altar of sacrifice and, later, in the temple in Jerusalem. The offerings included unblemished male or female goats, sheep, or cattle, depending on the type of sacrifice. Grain offerings included flour or grain (at times with oil), salt, or incense; no honey or leavening was permitted.

Six ceremonial actions were conducted with most of the sacrifices:

1. Presentation of the sacrifice at the door of temple or on the north side of the altar.

2. Laying hands on the sacrificial victim. The worshipper or priest laid his hands on the sacrifice to consecrate the offering to God and to make the sacrifice the offerer’s substitute.

3. Slaughter of the animal.

4. Sprinkling or pouring of the blood. For most animal sacrifices, the priest collected the animal’s blood and sprinkled a portion of it on the sides of the altar and poured the remainder at the altar’s base.

5. Burning of the sacrifice. Depending on the sacrifice, the priest burned part or all of the animal on the altar.

6. Partaking of the sacrificial meal.

As a disciple of Jesus Christ and as a student of the scriptures, I can see significant elements of Jesus Christ and His Atonement in all six ceremonial actions of these sacrifices, which were offered as a “similitude of the sacrifice of the Only Begotten of the Father” (Moses 5:7). Consider action 2, for example: When the temple worker (for example, priest or high priest) laid his hands on the head of an animal, he was symbolically transferring the sins of humans to the animal; then the animal was slaughtered in the prescribed manner. In a sense, the act of laying on of hands served as a conduit from the human to the animal. Thus the passage reads, “Aaron shall lay both his hands upon the head of the live goat, and confess over him all the iniquities of the children of Israel, and all their transgressions in all their sins, putting them upon the head of the goat” (Lev. 16:21; see also Lev. 1:4). The laying on of hands on sacrificial animals symbolizes Jesus Christ’s divine sacrifice, when He took upon Himself all of our sins and iniquities. This divine, infinite act has eternal consequences to me personally.

2. Laver

Camille Fronk Olson (MA ’86, PhD ’96), professor of ancient scripture: The laver stood in the courtyard between the altar of sacrifice and the door of the tabernacle. Cleanliness was essential for being in God’s presence. In a practical sense, priests needed to wash often in connection with their role in the slaughtering and sacrificing of animals. Spiritually, the ritual signified being freed from the blood, dirt, and impurities of sin and the world. In this way priests presented sacrifices and themselves before God in a state of purity and holiness.

The New Testament identifies ways that Jesus Christ may typify aspects of the tabernacle and later temples. Latter-day Saints resonate with such connections to Christ because we embrace the truth that “all things bear record of [Him]” (Moses 6:63). We have in Jesus Christ “a greater and more perfect tabernacle, not made with hands, that is to say, not of this building” (Heb. 9:11) whom we “draw near with . . . [with] our bodies washed with pure water” (Heb. 10:22). Like the Old Testament priests, we also come before God only after He washes us clean. Hours before His crucifixion, Jesus washed the feet of His Twelve Apostles in a ritual that could purify them in ways that they could never do themselves (see John 13:1–17). Likewise, when we are washed by being immersed in the waters at baptism, the ritual symbolizes the purifying power of the Lord in cleansing us beyond what water alone can do.

3. Menorah

David Rolph Seely (BA ’81, MA ’82), professor of ancient scripture: The golden lampstand—the menorah—is described in Exodus 25:31–40. It was made of pure gold, and its construction is described in terms of an almond tree with its branches, buds, blossoms, and flowers. The Bible does not describe its height, but Jewish oral tradition maintains that it was just over 5 feet tall (Babylonian Talmud Menahot 28b). The menorah had a central axis with three branches on either side, each bearing a cup at the top that was filled with pure olive oil and that served as a lamp. The function of the seven lamps was to light the Holy Place in the tabernacle.

Olive oil in the Old Testament is connected with the Spirit. When Saul and David were anointed with olive oil, the Spirit came upon them (see 1 Sam. 10:1–10; 16:13). The oil in the lamps of the 10 virgins (see Matt 25:1–13), as described in the Doctrine and Covenants, represents the Holy Ghost (see D&C 45:56–57). And the anointing of Jesus is described as being done through the Holy Ghost (see Acts 10:38).

The Bible never specifically explains the symbolism of the menorah. But Jewish and Christian traditions have offered many interpretations. Some Jewish commentators explained it as a symbol of human knowledge being guided by the light of God. There are also Jewish traditions associating the menorah with the tree of life. And the seven lamps were seen to represent the seven days of creation and the seven days of the week. Philo and Josephus, Jewish historians living near the time of Christ, saw the symbolism of the central lamp as representing the sun with the six other lamps representing the moon and the planets. The apocryphal book Ben Sira described the central lamp as a metaphor for Sarah and her virtue that shines forth (see 26:16–17). In Christian tradition Jesus identified himself as “the light of the world” (John 8:12; see also John 1:9), which may have been a reference to the menorah. The Book of Revelation contains a vision in which the seven lamps represent the seven churches (see 1:12, 20).

4. Table of Shewbread

George A. Pierce, assistant professor of ancient scripture: The table of shewbread was one of three pieces of ritual furniture (with the altar of incense and the menorah) found within the Holy Place of the tabernacle. The material of which the table was made—wood overlaid with pure gold (see Ex. 25:23–30)—and its position within the structure signify its importance within tabernacle worship: the rites conducted outside using the altar of sacrifice and the laver were oriented toward individuals, while the worship inside the Holy Place focused on the people of Israel as a whole.

The bread on the table, which could be translated from the Hebrew lehem hapanim as “bread of the Presence,” symbolizes the people of Israel as a whole and their covenant with the Lord. It serves as a reminder of Israel’s need to have its life sustained by God’s presence. Priests baked 12 loaves weekly and installed them on the table every Sabbath day (see Lev. 24:5–9). The old bread was taken from the table and consumed by the priests in an act of communion between deity and the people of Israel. While many Christian interpretations of the table of shewbread invoke Jesus’s “bread of life” teaching (John 6:35), the context of Jesus’s statement refers to the manna that was given to Israel while they were in the wilderness. Rather, Christians, and Latter-day Saints in particular, can connect with the table of shewbread and its 12 loaves as a metaphor for a gathered Israel in the presence of the Lord, and the consumption of that bread by the priests as a symbol of sacrament bread consumed in remembrance of the Savior and His atoning sacrifice.

5. Altar of Incense

Shon D. Hopkin (BA ’97, MA ’01), associate professor of ancient scripture: Exodus 30:1–10 describes the altar of incense. It stood inside the Holy Place just before the veil that separated that room from the Holy of Holies. It was made of wood and overlaid with gold. Each corner had golden “horns,” which were also found on the altar for burnt offerings and which likely symbolized the power of God (see, for example, Deut. 33:17; 1 Sam. 2:10).

The priests burned incense daily on this altar, bringing coals from the altar of burnt offerings. The burning of incense marked the culmination of the morning and evening burnt-offering services. As the priest burned the incense, he offered the priestly blessing. The altar of incense came to symbolize the place of prayer in the tabernacle, as indicated in Revelation 8:4: “And the smoke of the incense, which came with the prayers of the saints, ascended up before God out of the angel’s hand.”

In the New Testament Zacharias was chosen to conclude one of the morning sacrificial services. He stood at the altar of incense praying when the angel Gabriel appeared with the message of the birth of John the Baptist (see Luke 1:5–17). The angel thus appeared to God’s servant at the place of sacred prayer, before the veil upon which were stitched angelic cherubim, with a message of restored gospel truth that Zacharias had to decide to accept or reject. This revelation through an angelic messenger effectively opened the dispensation of the meridian of time, particularly when Zacharias later chose to accept the message and his mouth was opened to prophesy before the people (see Luke 1:63–79).

6. Ark of the Covenant

Professor Seely: The ark of the covenant is described in Exodus 25:10–22. It was a chest constructed of acacia wood covered with gold on the inside and the outside. It was three feet, nine inches long and 27 inches wide and high. It was fitted with rings for two poles used to transport it. On the top of the chest was a golden cover called the mercy seat, and two cherubim rested on either side of the cover facing each other. Cherubim were composite creatures that are found in other ancient Near Eastern cultures, in which they functioned as guardians of thrones and sacred places.

According to the Bible the ark of the covenant had two functions. It was understood as the throne of the Lord, who is described as sitting between the cherubim (see 1 Sam. 4:4; 2 Sam. 6:2). Thus it represented the presence of God and was placed in the Holy of Holies, which could be entered only once a year by the high priest on the Day of Atonement. The ark also served as a repository of the covenant—hence its name—represented by the two stone tablets containing the Ten Commandments. Eventually, according to Deuteronomy, a scroll containing a copy of the law (see Deut. 31:26) was placed beside the ark, as well as a pot of manna (seeEx. 16:33–34) and Aaron’s rod (see Num. 17:1–11). The children of Israel took the ark of the covenant into the promised land, and it was eventually put into the Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple in the 10th century BC. It was most likely destroyed when the temple was burned by the Babylonians in 586 BC.

Each year on the Day of Atonement—Yom Kippur—the high priest took blood from a sacrifice on the altar into the tabernacle. Passing through the veil, the high priest sprinkled the blood onto the mercy seat as a symbol of the reconciliation between God and his people (see Lev. 16). The 16th-century Protestant reformer William Tyndale coined the English word atonement describing the at-one-ment of God and His people in this moment of reconciliation. This word as a noun and as a verb is central to Jewish discussions of the law of Moses and Christian discussions of the redemption of Jesus Christ. It is also a prominent word in the Book of Mormon.

In the book of Hebrews, chapters 8–9, Jesus and His Atonement are dramatically explained in terms of the high priest at the Day of Atonement, or Yom Kippur. Jesus, as the high priest, brought His own blood as the sacrifice and by sprinkling it on the mercy seat made it possible for all humans to return to the presence of God. Thus the ark of the covenant becomes for Christians a central symbol in the doctrinal understanding of the Atonement of Jesus Christ.

The following video tour was produced by the Huntington Beach Stake.