By Bradley R. Wilcox, ’85

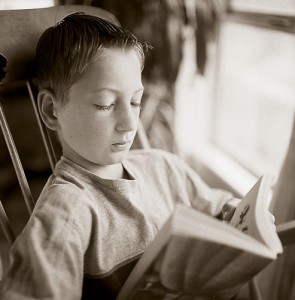

READING has been described as a child’s window to the world. Too often, however, adults block the very window they want children to open. None of us consciously bolts the window closed and stands there with a sign that says, “Stop reading!” but unless we are careful we can send the same signal in less-obvious ways. Here are some commonly heard phrases adults should avoid to keep reading windows wide open for children.

1. “Sound it out.” The joy of reading is in understanding a message, not in decoding words. If we place too much emphasis on figuring out tricky words, then reading becomes a chore rather than a joy. It is much more motivating for adults simply to provide the words youngsters are stumbling over and let them move on. How much would we enjoy a movie if the projectionist at the theater stopped the film every few frames to have us figure something out? There is a time for teaching phonics skills, but parents should help make reading time as smooth and enjoyable as possible.

2. “Look it up.” When confronted with new words, adults don’t usually interrupt an interesting book or newspaper article to go to the dictionary. Independent readers do not require dictionary definitions and pronunciation guides to make it through unfamiliar text. We need to allow children the same freedom. Dictionary skills are important and should be taught, but requiring new readers to look up every word they cannot read or write isn’t going to help them learn to love reading and writing.

3. “Don’t use your finger.” It is normal, natural, and even helpful for less-skilled readers to trace under words and mark their place with their finger. In fact, Dyad reading, a strategy pairing weaker readers with stronger ones, actually encourages the more competent reader to track the text with a finger as both read together—a process that has been shown to be very effective in helping children make reading progress.1 As children become more confident and independent, they automatically quit using their fingers as guides. Insisting they abandon this practice before they are ready, however, is a little like kicking a crutch out from under someone with a cast—it will probably prolong the time it takes for that person to function without the crutch.

4. “Don’t move your lips when you read silently.” Moving lips or even mumbling when reading silently does not get in the way of reading development. Insisting that a child stop does not improve reading ability. Such pressure simply causes a lot of frustration. Some adults claim they can read faster by not moving their lips, but many of those same adults do move their lips when they encounter challenging material or are trying to understand or internalize something new. Shouldn’t children be allowed the same opportunity? Demanding that a lip-mover stop usually goes about as far as trying to enforce a uniform sleeping position. People naturally find the position that is best for them.

5. “Let’s each read a paragraph in turn.” Going around the room taking turns reading is certainly a popular practice, but it is not an effective one. It creates high anxiety for the one who is on the spot and low involvement for everyone down the line. Few actually comprehend what is being read because often the reader is too nervous to listen to herself, the next ones in line practice their own paragraphs silently to themselves, and fluent readers lose patience quickly with children who stumble over words. Try reading chorally, going with volunteers, or varying the set order by choosing readers randomly and then allowing them to determine the length of their turns. It’s valuable to have everyone involved, but the involvement is often less threatening if they are simply following along in the text while a strong reader reads with fluency and expression.2

6. “Once a book is begun, don’t stop until it’s done.” There is nothing to be gained from forcing a child to finish a book in which he has lost interest. It may be a wonderful piece of literature produced by an award-winning author, but if the child doesn’t want to read the book, let him move on to another. It’s okay to close a book that hasn’t grabbed you just as it’s okay to discard a sweater that doesn’t fit. Some adults argue that “dull” books may turn out to have exciting endings if children will be patient, but waiting for the thrilling ending that may or may not show up is usually too much of a gamble for young readers. Often, in the time it takes to drag themselves to the end of a book they don’t like, they could have read two or three others they might have enjoyed.

7. “Read every word.” Consider how often we skim through a magazine or scan the headlines of a newspaper. We sometimes get all the information we want simply by reading titles, bolded print, captions under pictures, or subheadings. Why do we then accuse children of not “really reading” unless they read every word? Engaged readers are those who read for their own purposes no matter the age.3

8. “You can’t read another of your books until you read one of mine.” Encouraging children to read broadly is important and can be best accomplished by introducing them to lots of new titles, making a variety of books available, and reading some of your favorites to or with them. However, there is a big difference between encouraging and insisting. Just because we loved a book when we were growing up doesn’t mean our children should have to read it. Forcing new books—even classics—usually gets the same result as forcing new friends or foods. Instead of happily expanding their worlds, young people cling even more tightly to what is comfortable and familiar. If children seem hung up on horse stories, scary books, or fantasies, just be glad they are reading and not watchingTV. The more they read, the more they will naturally seek for new experiences. Telling children they can’t read a book of their choice until they read one we want often leads to no reading at all.4

9. “Don’t read the same book over and over.” Adults are sometimes concerned when children reread favorites. Yet how many times have we read our own favorite books or watched favorite films? When someone reads scriptures multiple times, we are not concerned. Instead, we realize there is much to be gained in subsequent readings. Parents can help stretch children from the “known” to the “new” by introducing them to other books by the same author, in the same genre, or that have similar characters or settings, but they should leave the final choice to the children.

Are we challenging children or dampening young readers’ motivation? Are we helping them learn to love reading or are we hindering their progress?

10. “That book is too easy (or too hard).” The worth of a book is not limited to the number of pages, level of vocabulary, or reading difficulty. Too often adults think that a book can’t be “good” unless it is right at the child’s grade level. While reading at level is important, “easy” reading—even comic books and cereal boxes—can be stimulating, rewarding, and motivating for some readers. Picture books and adolescent novels often have profound messages that can be enjoyed by children and adults alike. “Hard” reading rarely dissuades children who are interested in the topic. I’ve seen first graders devouring adult-oriented books on everything from dinosaurs and motorcycles to space and sunken ships. Adults enjoy a great deal of personal choice in reading material. Children should be granted the same privilege.

11. “Turn out that light and go to sleep.” Some of the best reading children do is under the covers with flashlights. If children are staying up so late they are missing sleep or disrupting the schedules of other family members, try setting an earlier bedtime, after which the only acceptable activity is reading.

12. “You can read now, so I shouldn’t have to read this to you.” Reading aloud is something that appeals to all ages and is not just a task we plod through with beginning or remedial readers. Listening to someone read can be a motivating and bonding experience as well as a valuable learning time.5 One friend explains it like this: “Maybe the real magic of reading aloud is not just found in ‘Once upon a time . . .’ but in once upon a dad or once upon a mom as parents hold their children close and read to them.”

Are we challenging children or dampening young readers’ motivation? Are we helping them learn to love reading or are we hindering their progress? These are important questions for which there are no easy one-size-fits-all answers. Perhaps the cautions mentioned above can help us clear the way for children to discover, open, and fly through reading windows now and throughout their lives.

Notes

1. J. L. Eldredge and D. W. Quinn, “Increasing Reading Performance of Low-Achieving Second Graders with Dyad Reading Groups,” The Journal of Educational Research, vol. 82 (1988), pp. 4046.

2. D. R. Reutzel and R. B. Cooter, Teaching Children to Read: Putting the Pieces Together, 3rd ed. (Upper Saddle River, N.J.: Merrill/Prentice Hall, 2000).

3. J. W. Irwin, Teaching Reading Comprehension Processes, 2nd ed. (Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 1991).

4. J. S. Jacobs and M. O. Tunnell, Children’s Literature, Briefly (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Merrill/ Prentice Hall, 1996).

5. J. Trelease, The Read-Aloud Handbook, 4th ed. (New York: Penguin Books, 1995).

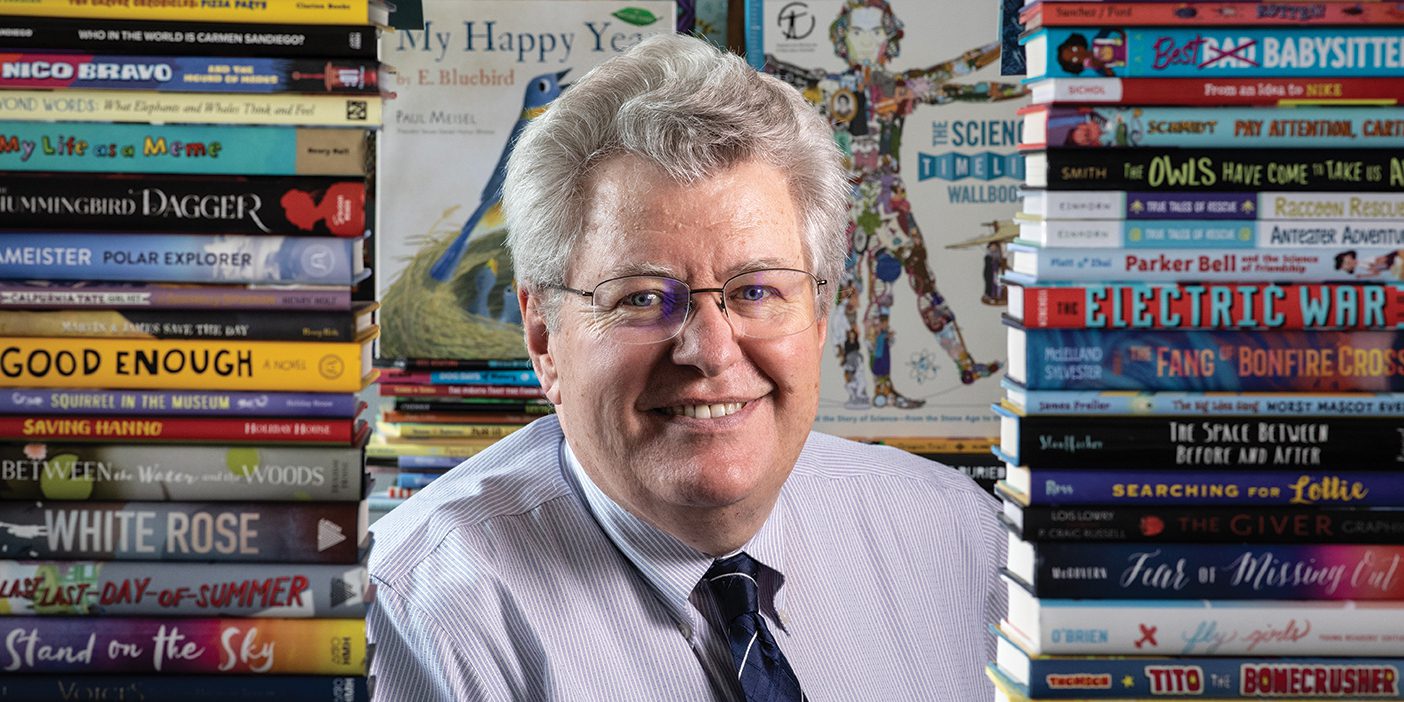

Brad Wilcox is an associate professor of teacher education who teaches classes in literacy and children’s literature. He is the author of many books for youth and children, including the picture bookHip, Hip, Hooray for Annie McRae!