By Michael Smart, ’97

ZOOLOGY

Ever in pursuit of rare fleas and other insects, last year BYU entomologist Michael Whiting also netted a prestigious research award.

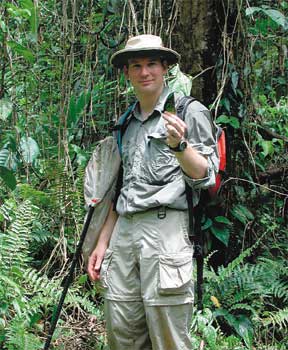

AFTER flying across the Pacific, then hopping from one remote highland airstrip to another, and hiking for a day through the plush mountains of Papua New Guinea, BYU entomologist Michael F. Whiting, ’90, peered up the trail, hoping to locate the isolated field station where he would collect obscure—and perhaps yet unknown—species of insects.

BYU entomologist Michael Whiting spent part of 2000 in New Guinea gathering rare insects like these walking sticks and the fleas that inhabit New Guinea’s unique mammals.

Peering back at him was a native New Guinean, a man who had never seen a car or running water, clad in a John Stockton T-shirt.

“They have all these hand-me-downs from various charitable organizations. I tried to explain to him who John Stockton was, but he had no notion,” says Whiting, an assistant professor of zoology. “It was just surreal to get up there and find someone with a Utah Jazz T-shirt on.”

Whiting’s enterprising spirit and the intellectual promise he has demonstrated through numerous publications and presentations of his research have earned him a Faculty Early Career Development (CAREER) award, the National Science Foundation’s most prestigious honor for junior faculty members. The citation brings renown within the national research community and, of more immediate importance to Whiting, a research grant of $500,000 spread over five years that will allow him to extend learning opportunities to more students. Two of Whiting’s Zoology Department colleagues, Keith A. Crandall and Edwin D. Lephardt, are previous CAREERwinners.

“CAREER awards support exceptionally promising college and university junior faculty who are committed to the integration of research and education,” says NSF Director Rita Colwell. “We recognize these faculty members, new in their careers, as most likely to become the academic leaders of the 21st century.”

A Provo native who used to hang out in the insect lab at BYU‘s Monte L. Bean Life Science Museum as a teenager, Whiting returned to teach at BYU after a stint as a post-doctoral researcher under curator Rob DeSalle at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

“They’re very highly perceived awards—they cement a researcher’s career,” DeSalle said when informed of his protege’s honor. “Mike’s a born teacher—one of the few who can explain lab techniques to students so that they can really grasp them right away. You put that together with a top-notch research mind and you’ve got a force to be reckoned with.”

Whiting’s mind is currently preoccupied with fleas. New Guinea has one of the world’s most unique populations of endemic mammals, and Whiting’s trip there was based on the belief that rare mammals would be harboring rare fleas.

“New Guinea stands as one of the last frontiers of biological research,” he says. “We went places no entomologist has ever been. There aren’t a lot of places left on Earth you can say that about.”

The two-month sojourn last fall followed a pattern. Whiting and his two assistants flew on a succession of increasingly smaller airplanes—”With one of them, I felt like I was climbing into someone’s old Volkswagen,” Whiting says—until they reached the airstrip nearest whichever mountaintop research station they needed. Then Whiting would hire a guide and about 15 locals to help carry his 440 pounds of mammal and insect traps, insect nets, and camping gear. A porter would clear the trail with a bush knife as they went.

“I’ve never been as exhausted in my life. The hiking was straight up almost cliff-like precipices and then straight down the other side, in searing heat and humidity,” Whiting says. “There are no large mammals over there, so there are no pack animals. The people have become exceptionally good at carrying heavy things long distances.”

After setting up shop at the research stations, Whiting would hire another 20 or 30 locals to help collect samples from the surrounding forests. In the five hours it took Whiting to capture 20 artfully camouflaged insects called walking sticks (another of his research subjects), a native could snare hundreds. The hired hands also handed Whiting live rodents and marsupials, which he then stroked with a toothbrush while holding them over a white bucket strategically positioned to catch fleas abandoning ship.

After he returned from New Guinea, the refrigerator in Whiting’s lab looked like a woodshed, it was so stocked with the folded remains of walking sticks, some up to two feet long. The precious fleas bobbed peacefully in tiny vials filled with preservative chemicals.

Whiting plans to use the money from his CAREER award to build the most comprehensive “family tree” ever constructed of the more than 2,300 known species of fleas, plus those he may have discovered in New Guinea. Some members of the far-flung flea family are hard to locate—he still needs a rare flea found only on the Tibetan barking deer (he doesn’t know if it actually barks) and another that calls Antarctic penguins its home. These insects that most people scorn as pests elicit a special fascination from the bug-loving professor.

“Fleas have long been associated with humans,” Whiting explains. “Back in the Middle Ages, they were just something you learned to live with.”

And die from. As the vehicles for the black plague that killed a third of the population of Europe during the 14th century, fleas have arguably impacted humans more than any other insect group, Whiting says.

This spring, a post-doctoral researcher from Germany will join Whiting’s lab and begin looking for signs of the plague in DNA extracted from the guts of fleas found in 1500-year-old Peruvian mummies. Whiting hopes the results might help identify where the plague originated and how widespread it was.

With the help of student researchers and BYU’s DNA Sequencing Center, Whiting plans to build the most comprehensive “family tree” ever constructed of the more than 2,300 known species of fleas.

But more motivating to Whiting than fleas’ history are the basic scientific questions that the organisms allow him to investigate.

“I want to understand the evolution of a very successful group,” he says. “Fleas have lived with mammals for a very long time and have evolved into many species. Why have they shifted onto new hosts? What environmental changes prompted those shifts?”

To get answers, Whiting enlists a team of students who bustle about his lab like excited Christmas shoppers the day after Thanksgiving.

His students first check specimens under a microscope, noting distinguishing physical characteristics. Then they carefully extract DNA samples and run them through BYU‘s relatively new DNA sequencer (see BYM Spring 1999, p. 18), which establishes the genetic blueprint of each animal and might, when the dozens of specimens from the trip have been analyzed, tell researchers they’ve discovered a new species.

“One of the reasons I was able to receive this CAREER grant was the NSF could see a strong institutional support for giving undergraduates research experience,” says Whiting. Last year one of his student researchers won an NSF Fellowship, an all-expenses-paid ride through graduate school that requires a rigorous research background at the undergraduate level.

With a lab full of fresh specimens gathered in the wilds of New Guinea, BYU entomologist Michael Whiting is building a national reputation.

In November 2000, two graduate students and two undergraduates traveled with Whiting to Montreal to present their research at the conference of the Entomological Society of America. Whiting also plans to take BYUstudents with him back to New Guinea this summer to help teach native students how to conduct biological inventories of pristine areas—another opportunity afforded by the CAREER grant.

“This award benefits the students, it benefits the faculty, and it really helps to accomplish the mission of BYU,” Whiting says.