By Study, by Faith, and by Experience

A new emphasis on experiential learning breathes life into the BYU educational environment.

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04), Jennifer J. Rollins (’17), Faith Sutherlin Blackhurst (’17), Kayci Kirkham Treu (’17), Andrea Ludlow Christensen (BA ’03, MA ’05), Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07), Michael R. Walker (BA ’90), Jennifer E. Ball (’17) in the Winter 2017 Issue

Illustrations by Mark Allen Miller

Kevin J Worthen (BA ’79, JD ’82) is a mission man. It seems that whenever the BYU president addresses an audience, phrases from the university’s 496-word mission document flow forth. In nearly every talk he explores BYU’s stated purpose “to assist individuals in their quest for perfection and eternal life.” And he draws just as heavily from the 3,445-word supporting document, The Aims of a BYU Education, reminding all that a BYU education should be spiritually strengthening, intellectually enlarging, character building, and lead to lifelong learning and service.

In all his speaking, he began to wonder if those nearly 4,000 words could be distilled into something more succinct. After discussing this with campus leaders, he created an impressively brief, two-word summation: “inspiring learning.” As he explained in his University Conference address in August, the term includes two meanings of the word inspiring: at BYU students should be inspired—or motivated to learn—and that learning should lead to inspiration. Inspiring learning, he argued, is most likely to take place when students facing real-life conundrums draw upon all their resources—academic and spiritual—to find solutions.

“Inspiring learning is most likely to take place when students facing real-life conundrums draw upon all their resources—academic and spiritual—to find solutions.”

While this sort of learning can take place in effective classrooms, Worthen contends that it is just as likely, if not more so, to happen while a student interns in a high-rise across the country, sequences DNA with a mentor in a campus lab, tests a second language with natives on study abroad, collects data points in the field, or even landscapes campus flower beds. Experience, says Worthen, “connects theory with application and deepens our understanding of the principles and truths we learn.”

Although the coinage and emphasis are new, Worthen points out that BYU was already no slouch in providing engaging, experiential learning. In fact, just as Worthen was unrolling plans to increase funding for such opportunities, the Wall Street Journal led into a September article announcing its 2016 ranking of America’s colleges thus: “Want a school that will engage your mind? Put Brigham Young University on your short list.” The engaged-learning category, where BYU took second, measured such things as colleges’ success in fostering critical thinking, connecting students to the real world, and building student relationships with mentors—all components of inspiring learning.

Following are stories of students being challenged, stretched, and deepened through experiential, inspiring learning.

Uncovering a New Plan

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04)

This wasn’t the plan. The plan involved sitting on a brightly lit stage in a black dress, drawing a bow elegantly across her cello’s strings. Instead, for a month last summer, a sweat-and-dirt-encrusted Hannah C. Lambert (’17) found herself sitting in a dusty pit in Galilee, her instruments a pickaxe and a trowel. Her audience? Curious cows and horses grazing in fields surrounding the archaeological dig. This wasn’t the plan, yet Lambert calls it “an unbeatable experience.”

Following a sophomore-year diagnosis of cubital tunnel syndrome and four surgeries, Lambert reluctantly let go of her music-performance ambitions, eventually settling on ancient near-eastern studies and biblical Hebrew. Last winter Matthew J. Grey (BA ’03), an ancient scripture professor, tipped off Lambert and four other students to an opportunity through the Jerusalem Center for Near-Eastern Studies to join him and University of North Carolina archaeologist Jodi Magness in field work. For five summers Grey and Magness had been excavating the site of a fifth-century synagogue in Huqoq, Israel. In the dig’s second year, a BYU grad had garnered international attention when he happened upon mosaic tiles depicting biblical scenes, and additional mosaics had been found each succeeding digging season.

Assigned to 5-by-5-meter plots, the team of students and experts from around the world scraped and sifted through historical strata: from the remains of a modern village, through Ottoman and medieval layers, down to the now-famous floor of the Late Roman–era synagogue.

Lugging dirt, taking elevations, and making daily sketches, Lambert and her peers were constantly on the lookout for discoveries—bones, coins, pottery sherds, or structural remnants. This year the team uncovered mosaic scenes of Noah’s ark and the Exodus.

But Lambert’s most important summertime discovery just might have been about herself: “It gave me that experience to say, ‘I could see myself doing [this],’” she says. Now exploring graduate schools, she has a new plan—one that brings her two loves into harmony: archaeomusicology, the study of ancient music through artifacts.

Making It Real

By Jennifer J. Rollins (’17)

The campus scene is common enough: two students and a professor in an office, laptops aglow, a nearby whiteboard covered in scribbled notes and mathematical symbols. It could be a professor untangling the abstract concepts of homework problems or helping students master theoretical principles for a midterm.

But for Adam P. Larsen (BA ’09) and Stefan M. Glufke (’17), MBA students in the BYU Analytics program, there is nothing theoretical about the challenges they are grappling with in the Tanner Building office. The duo is building a real algorithm for a real company with a real problem to be solved. Their task: help the data- and information-management business Sharpr precisely predict and retrieve online content for users based on their interests and preferences.

They are guided by Jeffrey P. Dotson, an associate professor of marketing who directs the newly created BYU Analytics program, which matches second-year MBA students with big-data projects. Within the past year Dotson-mentored teams have snagged awards at national case competitions and worked with companies ranging from Adobe to Kohl’s. With the Sharpr group, Dotson set up the team, got the students started with a basic algorithmic framework, and recommended sources to research to hone their analytical tool to more accurately find relevant and interesting content for individual users.

“It’s been great to work with him and learn from him,” says Larsen. “He is the technical expert and has been able to explain to us more in depth how the models work.”

Larsen says the experience has taught him as much about business communications as it has about algorithms. In conference calls with and presentations to Sharpr company executives, the team has learned to present complex information in simple ways and to highlight their progress in reaching the company’s goals.

It’s all part of the process of preparing the algorithm—and the students—to succeed in real-world environments.

“Experience connects theory with application and deepens our understanding of the principles and truths we learn.” —Kevin J Worthen

Let the Games Begin

By Faith Sutherlin Blackhurst (’17)

Ascending Rio de Janeiro mountain in a rickety cable car, BYU international business student Bryce R. Hawkey (’17) and other community-outreach interns for the International Olympic Committee (IOC) discussed their project for the week: building the Cantagalo-Pavão-Pavãozinho favela neighborhood’s first playground. As they disembarked, they emerged into disorder: brick and tin houses stacked precariously, mounds of trash, and encroaching jungle foliage that flourishes in the favela, as does drug trafficking and violence. After winding through a labyrinth of shoulder-width alleyways for several minutes, the team found their workspace—a small plot of land cleared and ready for rejuvenation.

Over the next four days, eager interns and favela residents labored through the muggy weather to dig holes for wooden posts, build jungle gyms out of tires, and install a stone barbecue for families to enjoy. Barefoot local children helped paint the cement steps that lead to the playground, adding brightly colored flowers and suns to the walkway. A local graffiti artist, commissioned by the outreach program, added touches to a mural promoting unity.

Hawkey says that for the humble residents of the favela, this is more than just a playground. It is a safe place for their children to thrive in the community, a place where they can forget their struggles and just be kids. It’s a symbol of hope that more opportunity will come.

Hawkey, who interned in Brazil for two weeks during the Olympics, says he now knows that international business is about more than just reaping profits. It can also be about giving back to the community and the world. “Often . . . we only see our own personal problems or those in our own communities and try to solve those, if we even do anything at all,” Hawkey says. “But I think through going and having experiences in other countries, we can recognize the greater need there is for such help.”

Alena and the Chocolate Factory

By Kayci Kirkham Treu (’17)

It was a weekday morning in Provo, and Alena C. Helzer’s (’17) roommates were still asleep. While lounging in her pajamas, she got a phone call—from Germany. “I want you to pitch your idea to our board of directors,” said Darren R. Ehlert (BS ’98), her former boss at the internship she’d just concluded with the Halloren chocolate factory. “Can we have a conference call in 15 minutes?” They had discussed the idea of promoting the company through microblogging. Now he wanted her to present that idea to the board of directors. From Provo. In German. In just 15 minutes.

“I was super nervous, Googling all these words I didn’t know, then giving a business pitch in my pajamas,” says Helzer. “It was the weirdest business experience I’ve ever had, but they loved the idea.”

During the summer term, armed with her mission German and excited to be mentored by Ehlert, a BYU grad, Helzer had interned in Ascheberg, Germany. Though she had no previous marketing experience, while at Halloren, Helzer developed new packaging for North American markets, worked with retailers like Costco to promote the brand, created content for social media, and even helped develop branding for a new product, Snickerdoodle Bites.

Working directly with “the bosses,” Helzer says the mentoring she received helped her not only gain admittance to BYU’s Marriott School but also grow personally and professionally. And it led to a part-time job after she returned to school. Thanks to her pajama-clad conference call, she now works with 300 bloggers across the United States to promote Halloren products.

“When people find out that I interned at a chocolate factory in Germany, they always ask, ‘Did you eat a lot of chocolate?’ which is just code for ‘How much weight did you gain?’” laughs Helzer. “The next thing they always ask is ‘So what did you do there?’ I never did typical ‘interny’ tasks, like making copies. I still don’t know how to use a copy machine.”

I Can Help

By Andrea Ludlow Christensen (BA ’03, MA ’05)

Looking up from his piles of paperwork, he saw her: an elderly Syrian woman, her weary face encircled by a traditional head scarf, slowly working her way into the office, aided by a walker, pausing to rest every few steps.

Interning as part of BYU’s Scandinavian Studies Program, Brady A. Stimpson (’19) had been hired by an immigration attorney in Turku, Finland, to help coordinate interviews with refugees flowing in from Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Afghanistan. On this particular afternoon, he watched as his boss, speaking Finnish, began asking the woman for her basic information.

But the woman was soon sighing, clearly frustrated by the language barrier, and Stimpson’s boss wore a “here-we-go-again kind of look,” recalls Stimpson. “It became abundantly clear that this wasn’t going to work.”

So the Idaho farm boy, who speaks Arabic and worked with refugees in high school and during his mission to Finland, took a deep breath, said a quick prayer, and approached the two. “Hi, I’m Brady,” he announced. “I speak Arabic. I can help.” The woman’s face immediately brightened. He soon learned that the woman had come to Finland 20 years prior seeking asylum but was still struggling to gain citizenship.

By the end of the conversation, Stimpson says, because “we were all making an effort to understand each other, there was a strong feeling of friendship and love.”

As he assisted the woman to her taxi afterward, he says, he had a “light-bulb moment”: this is where he could make a difference, lightening the burdens of refugees through an understanding of law and language.

Now pursuing a degree in economics with his eye on law school, he says the experience in Finland has “made all of my studies more engaging, more exciting, more purposeful.”

Dishing Shakespeare’s Dirt

By Brittany Karford Rogers (BA ’07)

Katherine L. Bowman (’17) can tell you all about Shakespeare’s rubbish pit. For one thing, he ate a lot of meat.

“They even found charred pork bones,” Bowman exclaims. Charring meant cooking the whole pig at once and suggests a meal with enough people to eat it. It’s evidence, as Bowman puts it, that “Shakespeare partied it up.”

After a summer spent in Stratford-upon-Avon as the first-ever intern at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, Bowman can dish all sorts of Shakespeare facts. The trust maintains properties and artifacts in the bard’s hometown, including the plot where Shakespeare’s home once stood. A recent excavation there revealed the rubbish pit—and sparked an idea that helped Bowman raise the money to renovate the entire site.

“I made almost 200 percent of our goal,” beams Bowman, who was set loose to court a new donor demographic for the trust. “There are a lot of people who love Shakespeare who are willing to give $100, $20,” Bowman explains. “But there was no real outlet for those people to be involved.” So the BYU English major became a Kickstarter master.

Dangling 14 different rewards, her campaign solicited donations from £1 to £1,000. The clincher gift: earth on which Shakespeare stood—dirt taken from the excavation strata.

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust board of directors almost wouldn’t have it. “They contested that donors would pay quite a bit for this sort of relic,” says Bowman, who proposed sending a vial of dirt to anyone pledging just £50. In what she calls “a stressful rhetorical moment,” she advocated for reaching out to a swath of Shakespeare lovers not necessarily well funded but passionate all the same.

The presentation worked. And the Kickstarter campaign brought in nearly £14,000.

“Funneling all that soil into the vials was a very dirty way to commune with Shakespeare,” laughs Bowman, who filled them herself. They used funds to reimagine Shakespeare’s home at New Place with gardens and an exhibit. And the experience has done more than enrich her coursework. Bowman reflects: “The ambition and confidence I gained from this internship flow into my entire life.”

“Want a school that will engage your mind? Put Brigham Young University on your short list.” —The Wall Street Journal

Clear Skies with a Chance of Worms

By Michael R. Walker (BA ’90)

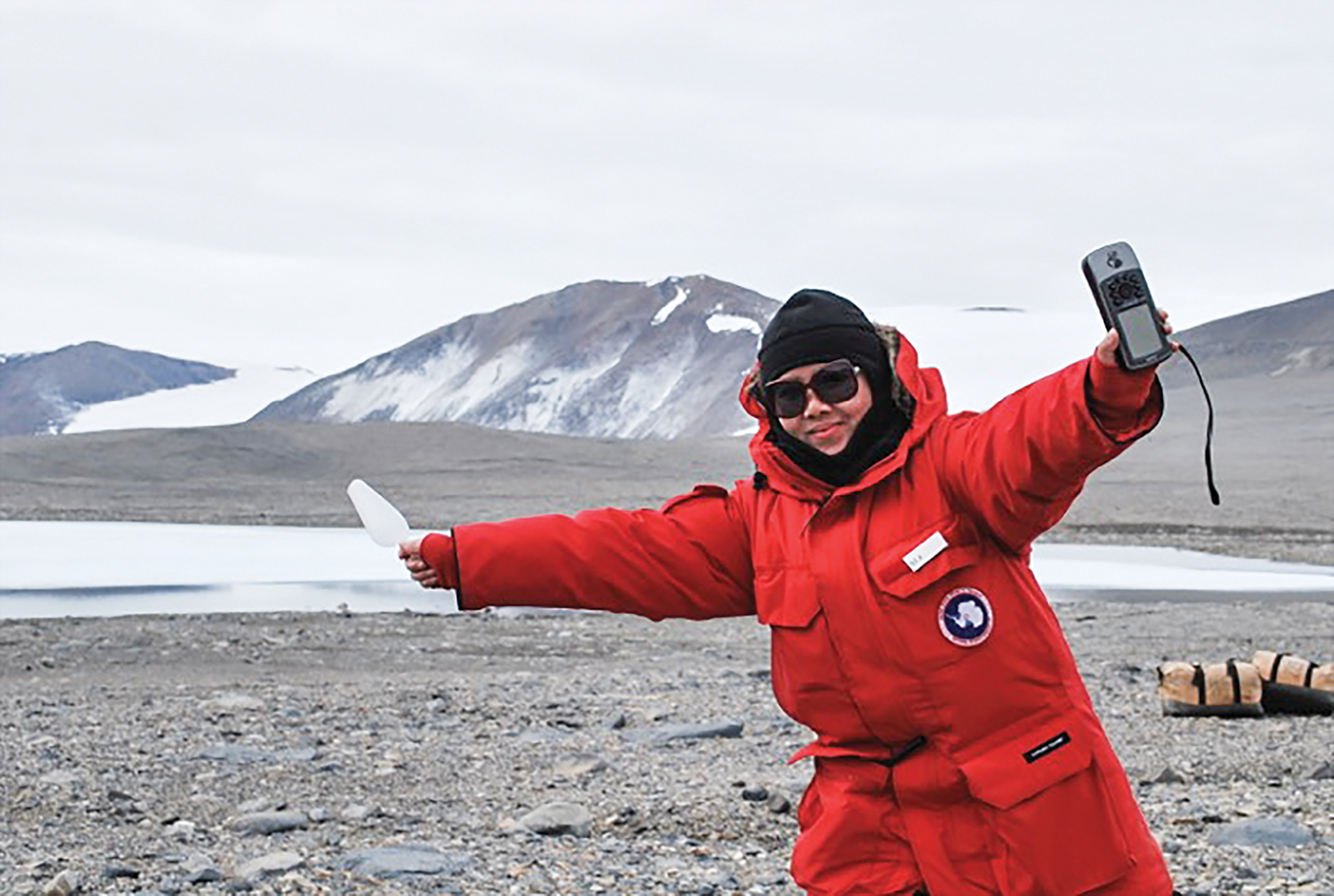

Lab work can be tedious. “Washing samples in the sink makes me feel like I am doing the dishes at home,” says biology grad student Xia “Summer” Xue (’18), who studies Antarctic nematode worms and other hardy microscopic organisms with biology professor Byron J. Adams (BS ’93). “I was thinking it was just my PhD project, just a path I pursue for my degree,” says Xue.

Xue’s outlook changed dramatically during a recent trip to do field work in the southernmost continent. “The world is so big,” she says. “The farther you go, you feel like you know nothing.” After a tough week of travel, she was “totally shocked” by Antarctica’s alien landscape, a striking contrast to her smog-enshrouded hometown of Zhengzhou, China. “It is ice and white and the sky is so blue and the UV light is really strong,” she says.

No cities, plants, or land animals. At 20 degrees below freezing, there were no smells. The only sound was the gusting wind. “What can possibly live here?” she wondered.

But, working with Adams in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, she discovered that life was all around. “Every time I just dig the soil with my scoop, I am thinking, ‘How many [living] things can I get from this soil?’”

In the field the job of collecting samples and observing creatures under the microscope became fun, even a passion for Xue. “Every time we find a tardigrade [or water bear], . . . they look like they are dancing there and saying hi to you—and they make you feel happy.”

These different resilient creatures survive freezing conditions by either drying themselves out or generating internal antifreeze—a tenacity that inspires Xue.

Xue says understanding how Antarctic worms survive harsh conditions can impact our response to global climatic change—and even makes cleaning lab equipment worth it. She adds: “I never thought about how important what I am working on is until I had the opportunity to see Antarctica with my own eyes.”

Expanded Views

By Jennifer E. Ball (’17)

One night in early September 2001, 10-year-old Gianluca Cuestas (’17) ate a late meal with his parents at a Sbarro restaurant in the mall below the south tower of the World Trade Center. Nothing about their peaceful meal in the bustling center of commerce hinted that within days the site would be left in ruins following an earth-shaking terrorist attack.

Fifteen years later Cuestas returned to the site, now home to One World Trade Center, this time with pen and paper in hand. After ascending the new tower in a “Sky Pod”—an elevator that whisked him up to the One World Observatory while monitors on the wall presented a 360-degree digital time-lapse of New York City’s last 500 years—he took in a panoramic view of the Manhattan skyline for the first time.

Cuestas was not here as a tourist but as a student journalist for the New York Daily News. As the paper’s only intern, he had worn many hats: content aggregator, runner for quotes and information, and metro reporter. He had written articles on David Letterman’s retirement, local dining, even a murder, logging countless subway miles through the boroughs to investigate crimes and gain the trust of key sources. But for Cuestas, who looks forward to a military career, this assignment to cover the opening of the One World Observatory was the most deeply personal and moving experience of the internship, a day of patriotic self-rediscovery he couldn’t have had without his position at the newspaper.

From the 102nd-floor observatory, he watched as a curtain was lifted to reveal an amber-orange sunrise rising over his home city, suggesting to him the dawn of a new, post–Sept. 11 day. Thinking of the building, the city, and its culture, he began to cry. “This was mine. Those were my people,” he says. “What that new skyscraper represents is who we are. You can’t knock a New Yorker down. You can’t knock America down.”

Speaking to the World

By Jennifer J. Rollins (’17)

Crossing the stage to the green-marble-tiled podium, with its globe-and-olive-leaf emblem, recent BYU graduate Jamie D. Clegg (BA ’16) whispered to herself, “It will all be over in two minutes.” Not an expert on the environment, Clegg took a deep breath as she prepared to address diplomats in the United Nations General Assembly on the topic of climate change—in Arabic.

After submitting essays on the topic of multilingualism and global citizenship, BYU Arabic language majors Clegg and Rachel A. Lott (’17) were invited to attend the Many Languages, One World Global Youth Forum at Hofstra University in July. They joined other essay-contest winners from 36 countries, with 10 speakers for each language represented in the United Nations (Arabic, English, Chinese, French, Russian, and Spanish). The Arabic language group was randomly selected to study and prepare speeches on climate change.

Despite her jitters, Clegg found that five classes from Asian and Near Eastern languages professor Spencer D. Scoville (BA ’02) had prepared her for this moment. “[He] really focuses on speaking and connecting with people in a way that’s meaningful to them, and that has served me really well.”

Though speaking at the UN was a highlight, Clegg says she learned the most from her interactions with her fellow participants as they worked together to prepare their speeches. Most of her peers already had impressive résumés and many languages under their belts. Some were finishing medical residencies or had started their own NGOs.

As Clegg begins to apply to graduate schools in comparative literature in Arabic, she remembers the lessons these friends taught her. While many had lacked access to money or good education, Clegg says they didn’t let circumstances hold them back. “[They] showed me that there is nothing stopping me from making a difference but me.”

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.