BYU researchers work to help bring a frog species back from the brink of extinction.

In the life cycle of the frog, appendage-challenged tadpoles undergo a dramatic change, a metamorphosis that allows them to make the evolutionary leap from water to land. But as a species, the Columbia spotted frog has experienced a backward leap in the last 40 years, from an abundant, common species in Utah to one on the brink of extinction.

On a late-summer morning near Park City, Utah, BYU researchers and their Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (DWR) colleagues stand together in a bog, where they hope to bring the spotted frog back to Utah’s wetlands. After an expectant summer of egg gathering, tadpole rearing, and frog feeding, today they will release a new population from protective enclosures on the Swaner Nature Preserve.

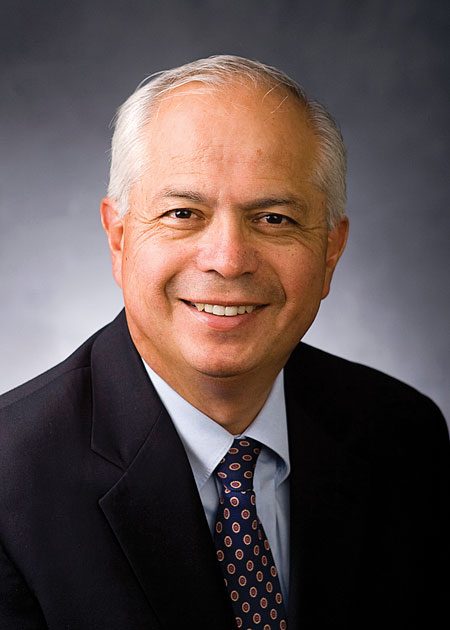

“One of the most important steps we can take to recover this species is to reintroduce it to the places where it once was, but where it no longer occurs,” says Mark C. Belk, ’85, a BYU associate professor of integrative biology who specializes in aquatic ecology.

For the Columbia spotted frog, once a common resident of Utah springs, streams, and ponds, decades of construction projects have created a housing crisis. What may have been hundreds of thousands of frogs dwindled to just hundreds to thousands in only a handful of population clusters. Aggressive conservation efforts—at a cost of nearly $1 million—have kept the frog population from declining further.

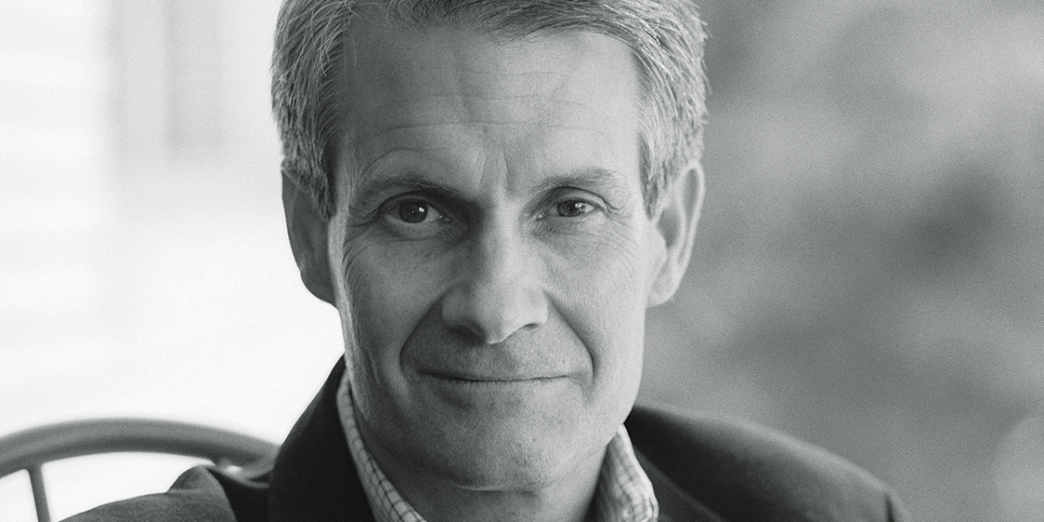

“They were in danger of being listed as an endangered species,” says Kristine Wengreen Wilson, ’96, a biologist with the DWR. “They were fairly close to being extirpated if we had not taken steps to enhance and protect their population.”

Ecologists recognize that declines in frog populations are not isolated, trivial events. Frogs are considered indicator species. Because of their thin, porous skin, frogs are hypersensitive to environmental disturbances, from pollutants to UV radiation.

“They are much more vulnerable to stresses in the environment which could eventually affect human populations,” says Wilson.

State biologists first began surveying spotted-frog populations in 1991, after noting declines in both frogs and frog habitats. By 1994 they recognized that the frog was in trouble and by 1996 had begun working on a conservation agreement to stabilize the population and avoid federal listing.

“We want to be proactive and protect the populations so they don’t get to the point where they have to be listed under the Endangered Species Act,” says Wilson.

Belk, with post-doctoral associate Erik Harvey and about 25 BYU students, has been conducting research with the DWR to improve the science of habitat selection and frog relocation.

This year’s fieldwork began in the spring on a gentle stretch of stream in Heber, where hundreds of gelatinous frog eggs floated on the surface like clusters of soap bubbles. Belk and his students scooped the egg clutches into plastic BYU Creamery buckets and brought them to a makeshift frog nursery on campus.

“Normally you would find about a 10 percent survival rate of these frogs through the tadpole stage,” says Belk. “Our goal is to help the frogs survive through that really vulnerable stage.”

As they matured, the clear egg sacs revealed their amphibious cargo, which morphed from ink-black decimal points to bold, wriggling commas. Once the tadpoles hatched and grew strong enough, Belk, Harvey, and a crew of students moved 4,000 to a new habitat near Park City, placing half in protective enclosures and half in the ponds outside the enclosures. BYU student R. Allen Phelps II, ’05, trekked to the site every other day to feed the tads a pureed spinach mixture and to collect data on the ponds. Now, in mid-July, the frogs are ready to be marked, measured, and released.

“Today’s a culmination of two years of work for me,” says Phelps, who was previously involved in other spotted-frog habitat and development studies. “We have been working with these frogs for a long time, and today we get to pull them out and actually see some data on them.”

This new habitat, the Swaner Nature Preserve, is a grassy marshland adjacent to an arterial freeway and a busy shopping hub. Its manmade ponds, in places, have the consistency of chocolate cake batter. Walking through the wetland, what looks on the surface like a safe, grassy nub suddenly gives way underfoot with a cool, juicy “glumph.” While this is not easy terrain for humans, it is ideal for frogs.

To take the inventory, Belk and his students, clad in rubber hip waders, stand in the middle of the pond and skim each enclosure surface with a fine net, sifting through the mud by hand and counting aloud as they separate frogs from silt. As the first enclosures are inventoried, the team is ecstatic.

“Today, it looks like we’ve got about a 90 percent survival rate overall, which is almost unheard of. It’s incredibly high,” Belk says, noting that the survival rate in the wild is only 5 to 10 percent.

But in the days that follow, Belk and his team find wide variation in survival rates from the other ponds. The average is 30 percent, still much better than the survival rate in uncontrolled populations.

“We now have a much more refined set of characteristics so that we can be much more efficient in terms of our effort to start a new population,” says Belk.

After the frogs are weighed and measured, each is tagged with a fluorescent mark under the skin to indicate its pond and enclosure of origin. In all, 750 frogs are released onto the preserve, not including those tadpoles that were released directly into the ponds. The BYU team will revisit the pond next summer to see how the frogs have fared. Belk says if 100 frogs survive, the population should be sustainable.

“Hopefully a breeding population will survive, and in a couple of years we’ll have lots of frogs,” he says.

“This is one of the most important on-the-ground projects that we have conducted,” says Wilson. “I really expect that within two years we’ll see egg masses, and within three to five years there will probably be thousands of spotted frogs spread out on the preserve.”

If federally mandated endangered-species protections are the proverbial “sticks” for property owners, then the state-based conservation agreements like this are the “carrots.” By paying landowners for conservation rights and making them preservation partners, the agreements, Belk says, help to “avoid the train wreck of opposing interests” that has characterized the fight over endangered-species protection.

“Here’s a really good example of a conservation agreement and working as a community to restore species and bring back a balance to maintain a complete system,” says Belk, who fights what is often an upstream battle to save endangered fish and amphibian populations.

“Sometimes we need to pay attention to odd and unpopular species because they are a part of that system. They’re important in terms of the ecology of the system, and the diversity that is inherent in a healthy system is also good for us.”

Oblivious to the million-dollar efforts and the countless hours of research in their behalf, the hundreds of freckled froglets climb and leap to elude their captors until finally, with a simple tilt of the bucket, they are free to hop into the pond. As the BYU team looks on, the frogs quickly dive and scatter, well on their way to survival as a species.

Julie Walker is the broadcast manager at BYU’s University Communications.