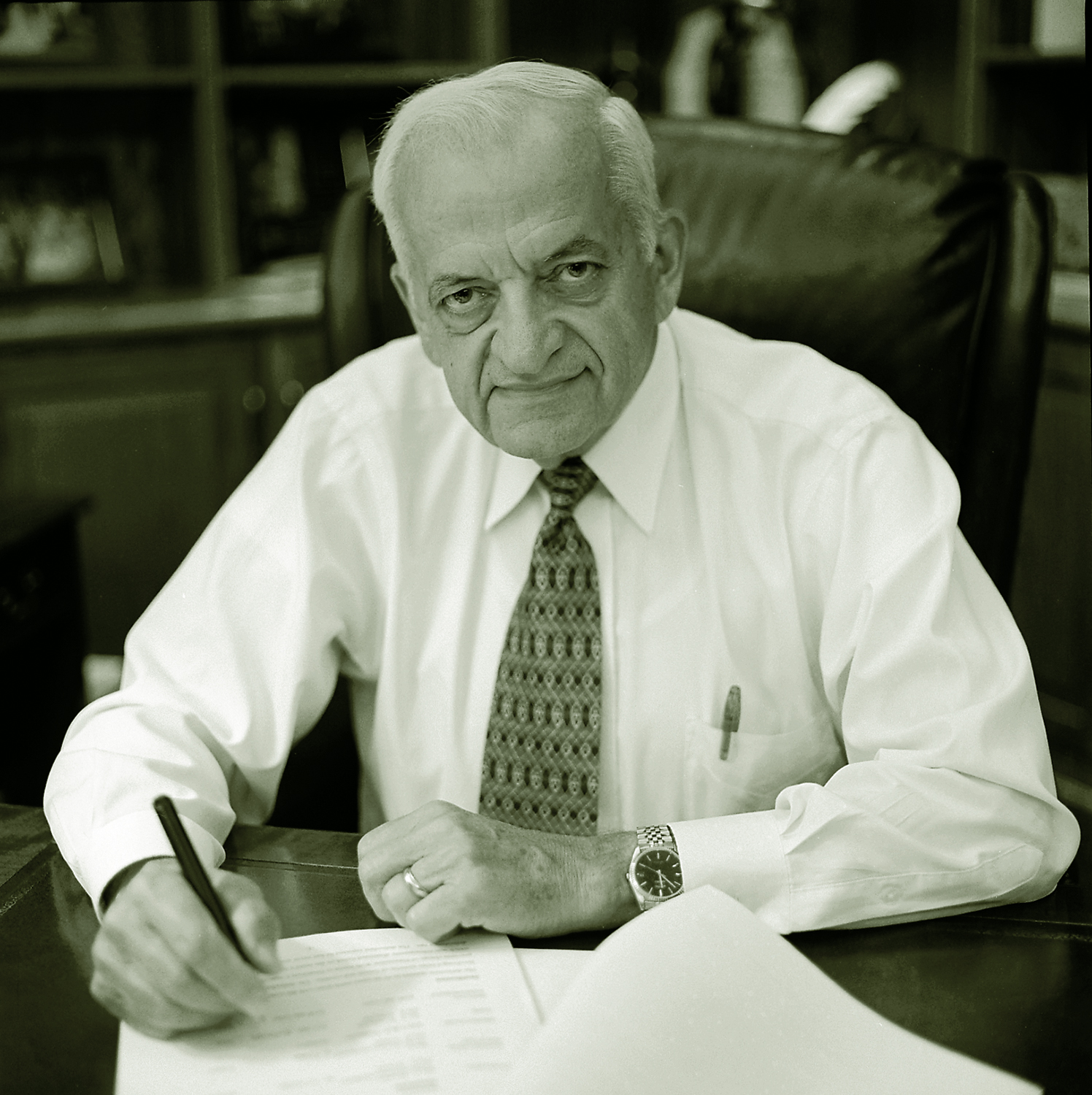

Sworn to uphold the U.S. Constitution, Thomas Griffith and 13 other BYU alumni apply their wisdom to the problems that come before the benches of U.S. federal courts.

As judges on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, Thomas B. Griffith (BA ’78) and his colleagues may play a more critical role in shaping U.S. administrative law than anyone else. The court’s jurisdiction over federal administrative agencies leads to its popular description as the second-most important federal court in the country, behind only the U.S. Supreme Court. And the two courts have another connection: In recent years four judges from the D.C. Circuit have made the move to the U.S. Supreme Court, including Chief Justice John G. Roberts, recently nominated by President George W. Bush and confirmed by the Senate.

Griffith, BYU’s general counsel from 2000 to 2005, appreciates the rare and important opportunity before him.

“It’s the highest professional honor that I’ve ever received, to be nominated by this president to this court and then to be confirmed by the Senate,” Griffith says. “It’s really a humbling experience.”

President Bush granted Griffith’s official commission June 29, 2005, 15 days after the U.S. Senate voted 73-24 to confirm him. But it wasn’t the first time Griffith had undertaken a major life change that involved heavy responsibility.

Griffith, now 51, joined The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a junior at Langley High School in northern Virginia. The decision aroused curiosity among friends, but Griffith did not allow others’ doubts to slow his own progress.

“I think, and I hope, that they saw that becoming a Latter-day Saint was a good thing for me,” Griffith says. “I tried to persuade them it would be a good thing for them. I never felt any disadvantage at being a Latter-day Saint.” Just months after joining the Church, Griffith successfully campaigned for student body president. He became the first of several LDS student body presidents at Langley High.

After high school Griffith studied at BYU, taught in the Church Educational System, and eventually attended the University of Virginia School of Law. He then practiced law for a decade in North Carolina and Washington, D.C., before being named to the nonpartisan position of Senate legal counsel.

In that capacity Griffith provided legal advice to the United States Senate on a variety of issues, including a high-profile constitutional challenge to the 1996 Line Item Veto Act and the 1999 Senate impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton. During the intense and politically charged impeachment trial, Griffith “proved his ability to fairly and impartially interpret the law,” said Senate majority leader Bill Frist.

While practicing law in Washington, D.C., and then as the Senate’s top lawyer, Griffith lived with his family in northern Virginia. Associating with the racially and economically diverse membership of his Church ward there, Griffith says he learned some valuable lessons.

“It was a reminder that the Lord really does not care about position or prestige,” Griffith says. “His interest and concern about what’s happening in the Senate of the United States is no greater than his interest and concern about what’s happening in the lives of people who are disadvantaged and struggling with some of the basic issues of life.”

Editor’s Note: This summer, as Thomas B. Griffith prepared to assume his position on the D.C. Circuit bench, Edward L. Carter (BA ’96) asked the new judge a few questions about his life, his experiences, and the American legal system. Carter is a BYU assistant professor of communications, a graduate of the J. Reuben Clark Law School, and a former law clerk for Judge Ruggero J. Aldisert of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Carter: What experiences did you have as an undergraduate student at BYU that made a difference in your life?

Griffith: I appreciated most having faculty and peers who saw no need to create false distinctions between the life of the mind and the life of the spirit and who modeled that to me. When I joined the Church as a junior in high school, I mistakenly assumed that my commitment to the Restoration would require that I put to one side the life of the mind. Because I was convinced that the Restoration had occurred, that was something I was willing to do. When I came to BYU I discovered that not only is that not necessary but that it would be a mistake to do so. In the grandest traditions of the Restoration, discipleship and intellectual rigor are part of the same enterprise. Seeing professors and peers who modeled that was the greatest part of my BYU undergraduate experience—that and watching Danny Ainge play basketball and Gifford Nielson play football.

Carter: In what ways can BYU—through the J. Reuben Clark Law School and graduates who pursue legal careers—improve the justice system?

Griffith: I can think of three ways. First, produce lawyers who approach their responsibilities with intellectual rigor. Second, produce lawyers who approach their responsibilities with a commitment to the highest ethical standards of the profession. Third, produce lawyers who are committed to creating a community that cares deeply about those who have been pushed to the margins of our society, those who haven’t yet reaped the full benefits of living in a society of constitutional government, the rule of law, and economic liberty. I would hope that lawyers trained at BYU, either as undergraduates or law graduates, would be deeply committed to looking for ways to care for those who have been left out or left behind—those the Savior refers to as the “least of these,” but whom He also calls “my brethren” (Matt. 25:40). I don’t mean to suggest every lawyer out of BYU must work as a public defender or in a social welfare agency, although many should. The ideas I’m referring to can be practiced by any lawyer, from the partner at the Wall Street law firm to the public defender.

Carter: The Barrett Prettyman U.S. Courthouse in Washington, D.C., where your new office is located, is about three blocks from the National Archives, where the U.S. Constitution is displayed. What has made the Constitution so enduring?

Griffith: In my view there are at least two reasons for its success. First, the brilliance and inspiration of the Framers to create a system of limited government, separated powers, and checks and balances. That created a foundation of principles that has set boundaries in the government yet has allowed sufficient flexibility between the branches of government to allow the Constitution to survive.

Second, the American people care about the Constitution. Notice how often the Constitution is invoked in our public debates. I believe the Constitution has survived because great men and women throughout the nation’s history have cared deeply about its meaning.

Carter: What is your greatest challenge as a federal judge sworn to uphold the Constitution?

Griffith: To uphold the Constitution. I think it is interesting that one must take an oath of office before one is allowed to be a judge. Even though I have been nominated by the president, the Senate has now given its advice and consent, and the president has now appointed me, I can’t assume the office of a federal judge unless and until I am willing to take an oath. That oath requires me to put to one side my own personal views about matters and instead to do my best to determine what the law is and then to apply that law impartially. That’s the challenge of a judge, to put to one side personal views.

In my view a judge in a democracy has a limited role. A judge is not there to determine what’s the right thing to do, according to her sense of fairness or justice. The judge should not make new law. The judge must apply the law that has been made by the people through the Constitution, statutes, and regulations. A federal appeals judge must also apply the law established through the precedent of the circuit and the Supreme Court. The greatest challenge of a judge is to act within those carefully circumscribed limits.

Carter: What are your most vivid memories of your time as Senate legal counsel?

Griffith: My most vivid memories involve the impeachment trial of President Bill Clinton, although, I have to say, my entire time as Senate legal counsel was memorable. There were many interesting issues. We were involved in the line-item-veto legislation. In that matter I was able to work with the acting solicitor general, Walter Dellinger, and later the solicitor general, Seth Waxman. Being able to work with those two remarkable lawyers is something I will always remember. But the impeachment trial stands out because it was so unusual. This was only the second time in the history of the nation that a president had been impeached by the House of Representatives and put on trial in the Senate.

Carter: What lessons did we, as a nation, learn (or should we have learned) from President Clinton’s impeachment in the House and trial in the Senate?

Griffith: I don’t know that I can speak for the nation, but I can share lessons I took away. One is the importance of the rule of law in a highly charged political environment. In some ways, I had a very easy job during the impeachment trial because my position was not a partisan position. My job was to remind the political players involved that the rule of law applies to the process here; that the Constitution sets forth some bedrock principles regarding the impeachment process; that there were precedents that had been established in the Andrew Johnson trial and other impeachment trials involving judges and other federal officers. Out of those experiences the Senate had learned some lessons and created some precedent. My job as Senate legal counsel was to remind the Senate of the body of law that governed the process by which an impeachment should be conducted and to advocate to the Senate that they follow the precedent in this setting, which they did.

Carter: You have volunteered your time and expertise in various capacities, from representing a death-row inmate to serving on a federal commission to review Title IX. How do these activities relate to your statement in 2000 that “the highest and most noble role of a lawyer, then, is to help build communities founded on the rule of law”?

Griffith: They are my meager attempt to try to do that. I believe that lawyers in the United States have a special obligation because we are the direct beneficiaries of this remarkable nation and the success it has had. We, of all people, have a special obligation to give back what we can when we can to help build the community and strengthen it. Lawyers who are trained in how to think about legal issues and how to become advocates have an obligation to use those skills to try to figure out how to make the republic stronger and how to bring people into the community who have been left out. Most lawyers I know do that.

This story hasn’t made it to popular culture yet, but it’s true: lawyers use their skills to help build community, whether it’s using their legal skills in pro bono activities, such as representing the indigent, or using their leadership skills to coach a softball team or work at a homeless shelter or a battered women’s shelter. Lawyers have an obligation to do those things. My observation is that they do them. I’m very proud to be an attorney, and I wince at the view that some in popular culture have about lawyers. I haven’t met many lawyers whose lives are close to the stereotype of popular culture. The lawyers I have worked with care about their communities and work to improve them.

Carter: You are an advisor to the American Bar Association’s Central European and Eurasian Law Initiative (ABA-CEELI), which was established in 1990 to advance the rule of law in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. What progress has been made in that regard, and what remains to be improved?

Griffith: Much progress has been made. ABA-CEELI and other providers of rule of law programs have been active in the region since the fall of the Berlin Wall and have been influential in helping these newly formed democratic states create societies based on the rule of law. Ukraine is a recent and dramatic example. There are many others. There are heroic men and women in that region who are, in my view, the modern-day Madisons, Jeffersons, and Washingtons for their own societies. They are interested in the rule of law, in reform, and in creating democratic societies based on limited government, individual liberties, and economic freedom. Because they are there, I have confidence that those countries will succeed.

There are great challenges remaining. The rule of law is a powerful idea, but it’s also a fragile idea, even in the United States. The rule of law is a concept that must be kept alive and must be rediscovered by every generation. It’s a fragile possibility. These newly formed democratic states in Central Europe and Eurasia have made great advances, but there’s much work yet to be done. Many of them were under totalitarian regimes for several generations, and the residual effect of that takes time to replace. They will do it because they have great citizens who believe in freedom. There are daunting challenges, but fortunately there are many—not just in the United States, but throughout the world—to help in that endeavor.

Carter: What are the strengths and weaknesses of the legal system in America today? What particular segment of society, if any, is not particularly well served by the legal system?

Griffith: I believe that the American legal system, by and large, works very well. Obviously, we can always do better. One way in which our society can do better is in representing the indigent. When I joined a team at my law firm that was representing a death-row inmate who was indigent, I was surprised to learn first-hand some of the challenges that face indigent defendants. I had not had prior experience in criminal law. It was new for me to work with an individual whose life hung in the balance. I got a better sense from that experience of how important it is to get good legal representation to those who can’t afford it because the consequences are so severe if the process doesn’t work well.

Carter: You told a BYU–Hawaii audience in 2000 that Robert F. Kennedy was your boyhood hero. Why was he your hero?

Griffith: He was such a passionate and articulate spokesperson for those who had not yet experienced the benefits of full participation in American society. He was a spokesperson on behalf of the poor and the dispossessed among us. Although over time my political views differed from his, I have never forgotten his passion for the “least” among us. He spoke of the need for reconciliation in our nation. That moved me as a boy. It inspires me still.

Carter: Who is the federal judge, past or present, you admire most, and why?

Griffith: That’s an easy one. I’m a Virginian. Every Virginian, and I think every American, admires John Marshall. Part of it is born of my Virginia roots, but it is also the great work he did in establishing the federal judiciary.

Supreme Alum

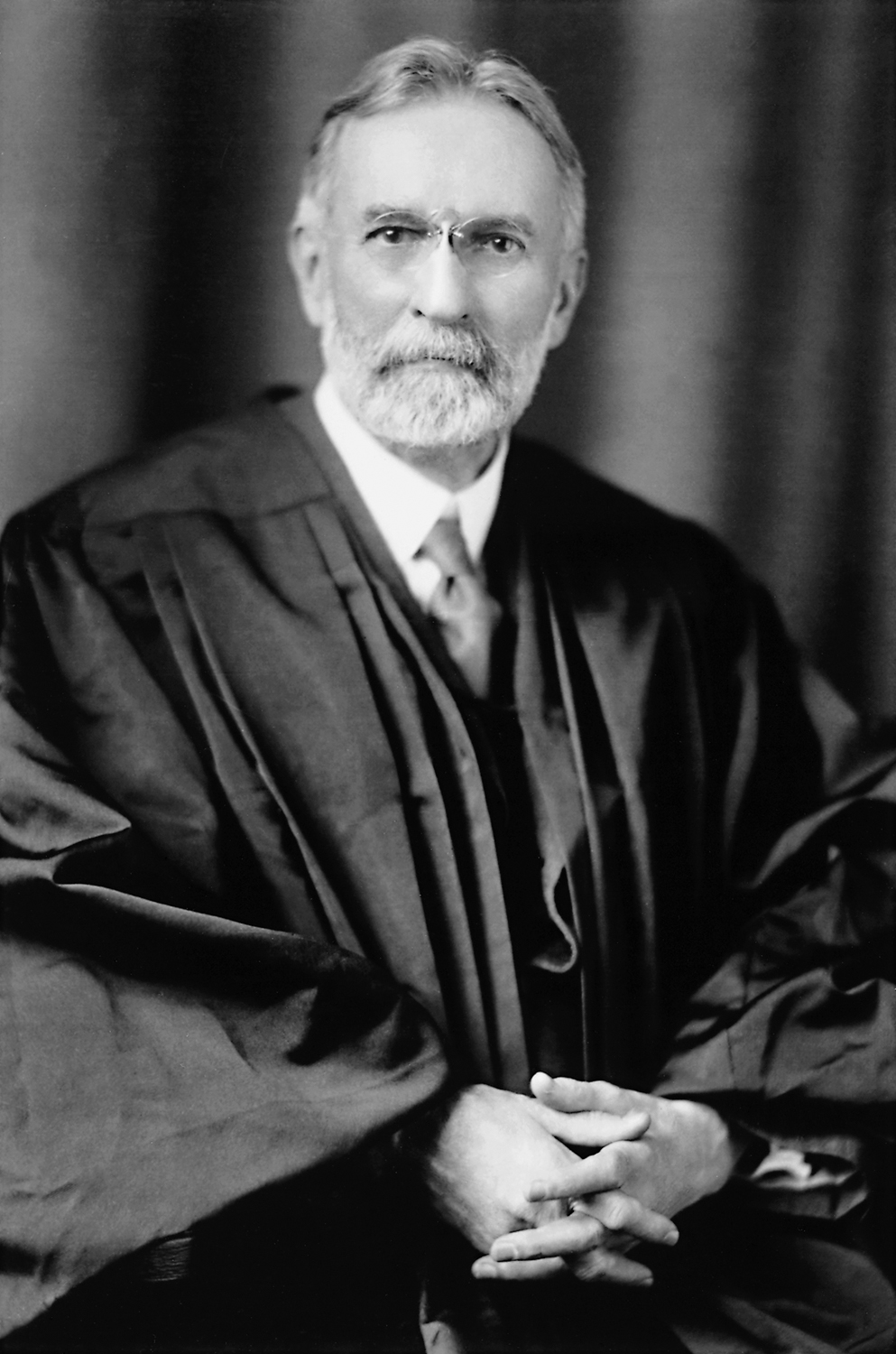

No one who has attended the Y has risen as high in the federal judiciary as British immigrant George Sutherland, who served 15 years as a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court. Appointed an associate justice in 1922 by President Warren G. Harding, Sutherland remains the only Utahn to serve on the Supreme Court.

In a BYU commencement address in 1941, just a year before his death, Sutherland detailed the influence on his life of Karl G. Maeser, the principal of Brigham Young Academy when Sutherland attended from 1879 to 1881. “[Maeser] was a man of such transparent and natural goodness,” said Sutherland, “that his students gained not only knowledge, but character, which is better than knowledge.”

Sutherland told friends that Maeser’s impact on his life “can not be exaggerated,” and in particular, Sutherland recalled in his later years that Maeser had taught him that the U.S. Constitution was divinely inspired.

After leaving BYA, Sutherland studied law at the University of Michigan and then practiced law in Provo and Salt Lake City. He served in the first Utah State Legislature in 1896, was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1900, and served from 1904 to 1916 as a U.S. senator from Utah. He also served as president of the American Bar Association in 1916–17.

—Edward L. Carter (BA ’96)

13 BYU Alumni Judges

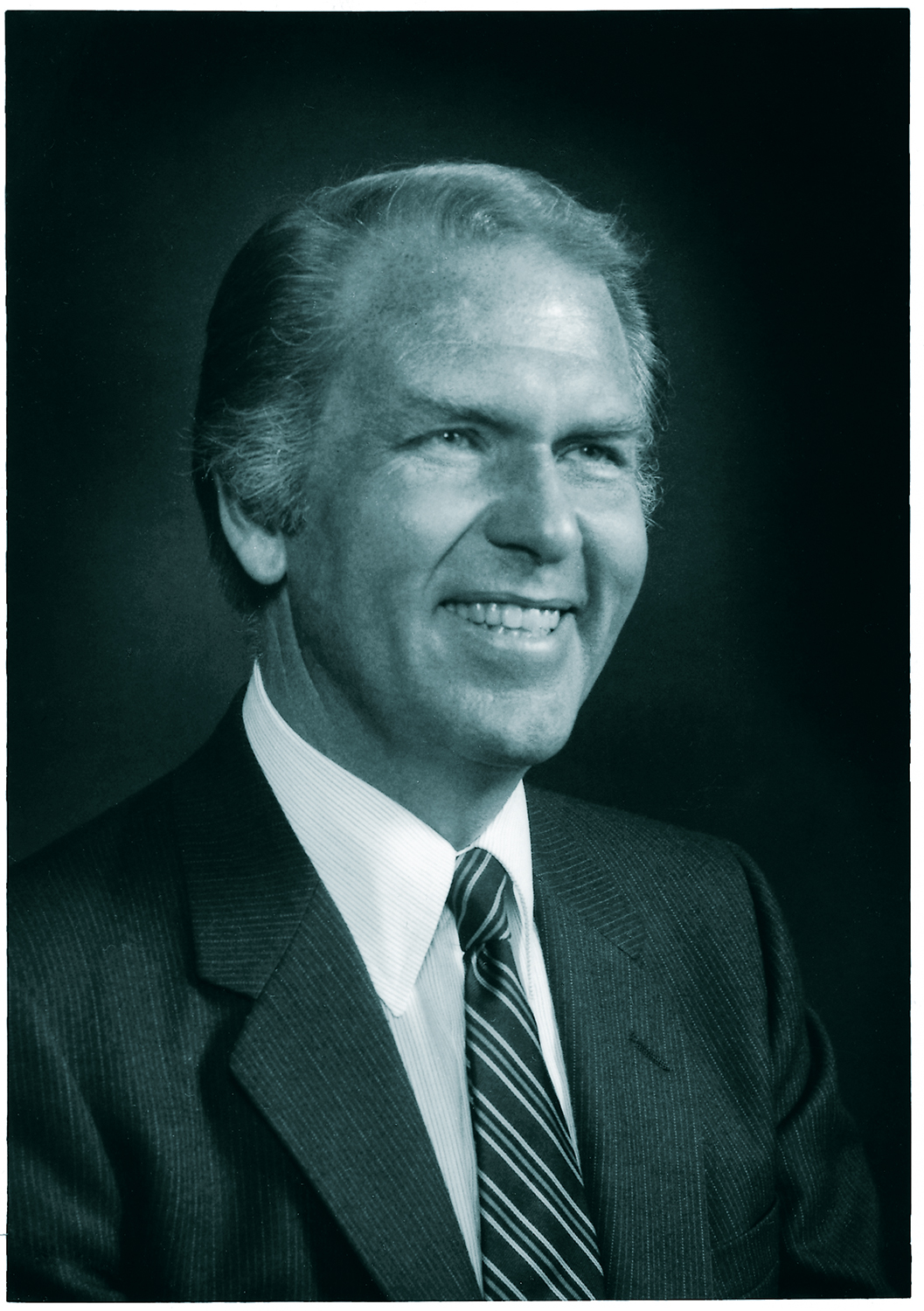

Judge Stephen H. Anderson

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

Appointed: 1985, President Ronald Reagan

Education: Eastern Oregon College of Education, 1951; BYU, 1956; LLB, University of Utah, 1960

Notable: In 1998 Judge Anderson wrote for a three-judge panel that Oklahoma did not violate highway patrol troopers’ Constitutional rights by ordering the troopers to remove campaign signs from their front yards but that the state could not force removal of signs posted by the troopers’ wives.

Quote: At BYU, he says, “I learned that cynicism is not an integral part of expanding your intellectual horizons. Too many other universities feel like you have to be condescending to the values you bring in to the university in order to adequately learn about new value systems. At BYU you could learn about other value systems and challenging things as a matter of building on to your current value system. . . . It is a foolish proposition that learning and cynicism must go hand in hand.”

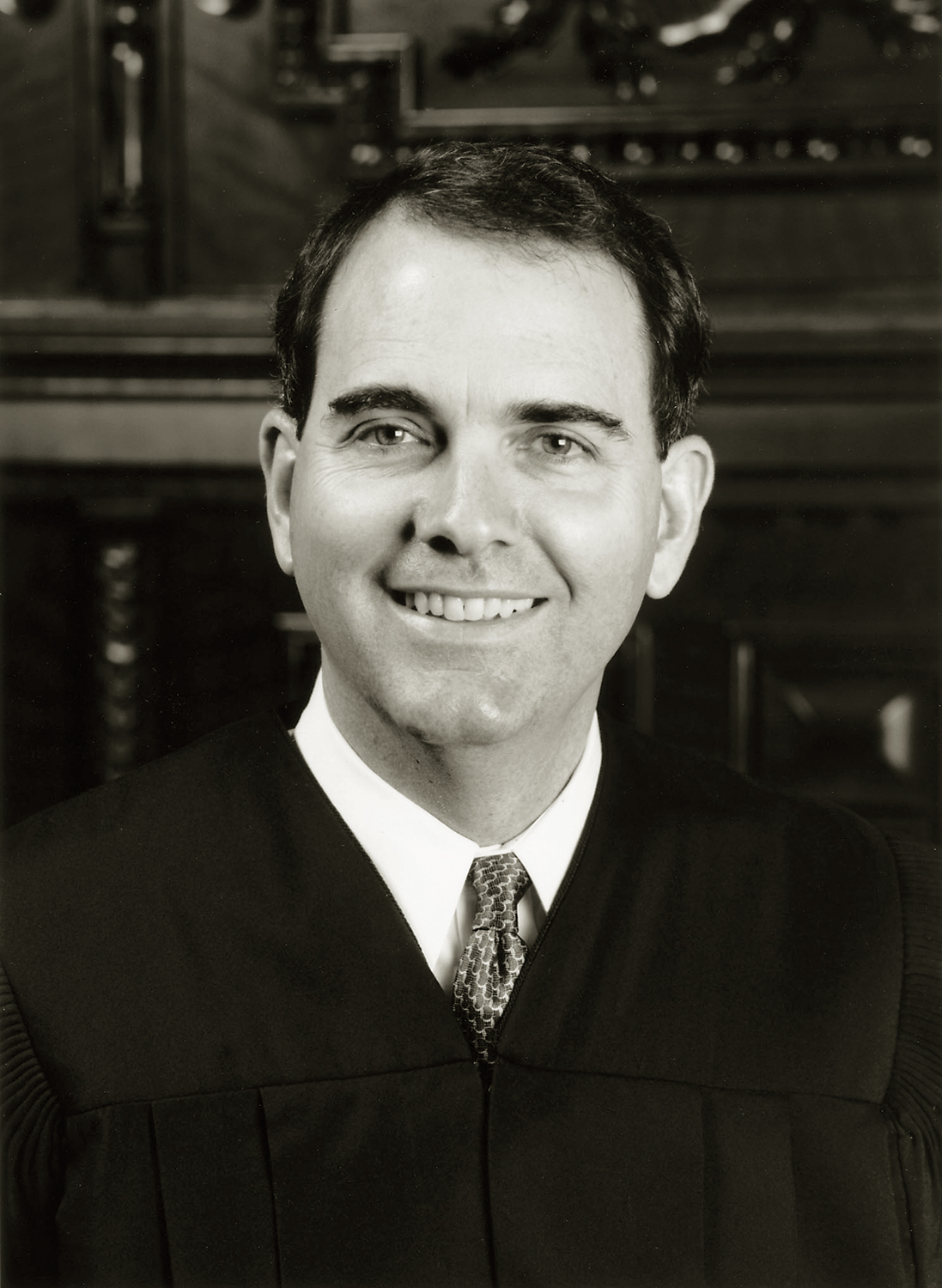

Judge Dee V. Benson

U.S. District Court for the District of Utah

Appointed: 1991, President George H. W. Bush

Education: BA, BYU, 1973; JD, BYU, 1976

Notable: Benson was a member of the charter class of BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School.

Memories of BYU: As an undergraduate student, Benson played soccer on the BYU men’s club team. The team played around the Intermountain West and at one point traveled to Italy for an 11-game tour. He later played professional soccer with the Utah Golden Spikers for one summer after law school.

Quote: “I can’t overemphasize how much going to BYU Law School changed my life. Rex Lee alone made it worth going to law school at BYU.”

Judge Jay S. Bybee

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Appointed: 2003, President George W. Bush

Education: BA, BYU, 1977; JD, BYU, 1980

Notable: From 1989 to 1991, Bybee was associate counsel in the White House.

Memories of BYU: A member of the fifth graduating class of BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School, Bybee went to great lengths to convince law firms that he merited a job. At one point he sent about 100 résumés to Washington, D.C., employers and flew himself there for a week to solicit interviews. His biggest asset was a recommendation from Rex E. Lee (BA ’60), then dean of the law school. “Rex’s name in Washington, D.C., went a long way,” Bybee says.

Quote: “I was exposed to lawyers of faith at BYU. Rex Lee was so impressive, and Dallin Oaks was just a giant in our eyes.”

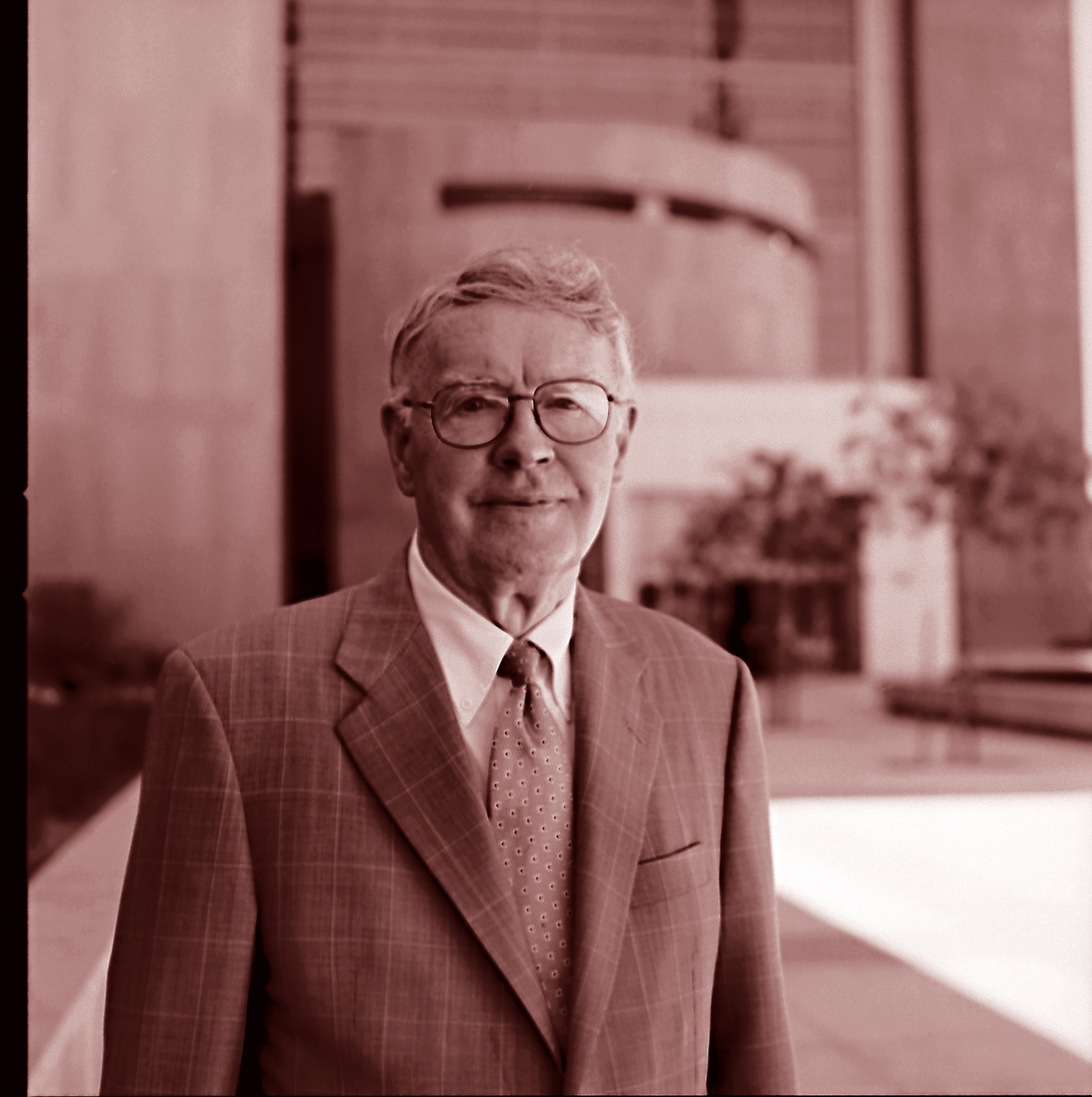

Judge Lloyd D. George

U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada

Appointed: 1984, President Ronald Reagan

Education: BS, BYU, 1955; JD, University of California, Berkeley, 1961

Notable: The eight-story, $96 million Lloyd D. George U.S. Courthouse in Las Vegas was named for him when it opened in 2000; he served as chief judge of the District of Nevada from 1992 to 1997, when he assumed senior status.

Memories of BYU: As student body president, he assisted in planning for the construction of the Wilkinson Center. He and classmates started a series of 7 a.m. Saturday meetings, to which they would invite selected faculty members. At one such meeting, attended by a Chinese professor who had met Gandhi, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Winston Churchill, and Joseph Stalin, George asked the professor who was the greatest. The professor’s reply sticks with George today: “My mother told me that not all great people were good but all good people were great.”

Judge Roger L. Hunt

U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada

Appointed: 2000, President Bill Clinton

Education: BA, BYU, 1966; JD, George Washington University, 1970

Notable: Judge Hunt held in June 2005 that a school uniform mandate did not violate a student’s rights.

Memories of BYU: As an undergraduate student, Hunt was a member of the BYU performing group Curtain Time USA, which toured Asia and the Middle East in the mid-1960s.

Quote: “The greater my education, I found, the stronger my testimony.”

Judge Robert C. Jones

U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada

Appointed: 2003, President George W. Bush

Education: BS, BYU, 1971; JD, University of California, Los Angeles, 1975

Notable: Jones is also a CPA and is a third-generation lawyer; his son, Justin, is also a lawyer.

Memories of BYU: As a student employee, he cleaned the David O. McKay Building at 3 a.m.

Quote: “Every case is a human story. You appreciate how human you yourself are. It’s a very heavy responsibility and an important one. It’s humbling to me.”

Judge Kent A. Jordan

U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware

Appointed: 2002, President George W. Bush

Education: BA, BYU, 1981; JD, Georgetown University, 1984

Notable: In 1984–85 he was a judicial clerk at the court where he now serves.

Memories of BYU: “I remember Freshman English Composition with Douglas Thayer. He wrote on one of my papers, ‘Keep this up and you may actually develop a style.’ I think it was meant to be encouraging, and I took it as encouraging. My job now is all about writing. It’s not writing of the sort that would grip a general reader but it does require clarity of thought and expression.”

Judge Dale A. Kimball

U.S. District Court for the District of Utah

Appointed: 1997, President Bill Clinton

Education: BS, BYU, 1964; JD, University of Utah, 1967

Notable: Kimball was a professor at BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School from 1974 to 1976. In 1996 the Utah State Bar named him Distinguished Lawyer of the Year.

Memories of BYU: He owns 12 football season tickets and has been to nearly every BYU bowl game.

Quote: “Being a federal judge is perhaps the best law-related job in the United States. The cases are fascinating, the lawyering is very good, the facilities are good, the help is good, and the pay is not bad—and they pay you until you die.”

Judge Michael W. Mosman

U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon

Appointed: 2003, President George W. Bush

Education: AB, Ricks College, 1979; BS, Utah State University, 1981; JD, BYU, 1984

Notable: Mosman served as a law clerk to then Supreme Court justice Lewis Powell.

Memories of BYU: Mosman played in the Law School’s midnight basketball league.

Quote: “I left [BYU] with the firm conviction, grounded in the example of my peers and professors, that one could live a good and decent life and succeed in the law. . . . The Law School was new and rising fast. It felt like almost anything was possible, even for a kid from Idaho with funny hair and a broken front tooth.”

Judge Monroe G. McKay

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit

Appointed: 1977, President Jimmy Carter

Education: BS, BYU, 1957; JD, University of Chicago, 1960

Notable: He taught at BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School from 1974 to 1977; he was then appointed to the federal appellate bench, and his investiture took place at the Law School, making a memorable impression on law students (including current Ninth Circuit judge Jay S. Bybee).

Memories of BYU: At age 25 McKay enrolled at BYU at the urging of his brother. He was sent to a remedial English class, and his first essay received a D- with a lot of red ink and a note from his teacher: “Monroe, you didn’t earn this but I didn’t want you to get discouraged.”

Quote: He interrupted his law practice in the 1960s to spend two years directing a Peace Corps program in Africa, where he had served a Church mission. “We made a habit of doing interesting things when the opportunities presented themselves rather than when they were propitious,” he says.

Judge Richard A. Paez

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Appointed: 2000, President Bill Clinton

Education: BA, BYU, 1969; JD, University of California, Berkeley, 1972

Notable: Paez represented indigent clients in California during the 1970s. Among other things, his experiences representing the indigent taught him that the justice system is often inaccessible to those who need it most. “Delivering legal services to people who need it is very difficult, and I’ve always been very sensitive to that,” he says.

Quote: “I enjoyed my days at BYU. It was a good place for me to go to school.”

Judge Randall R. Rader

U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit

Appointed: 1990, President George H.W. Bush

Education: BA, BYU, 1974; JD, George Washington University, 1978

Notable: Judge Rader has authored numerous books and articles on intellectual property law and other legal topics.

Memories of BYU: As an undergraduate student at BYU, Rader became the close friend of Michael Young, now president of the University of Utah. Rex E. Lee tried to persuade the pair to attend BYU’s new law school in the mid-1970s, but Rader chose George Washington and Young chose Harvard.

Judge David Sam

U.S. District Court for the District of Utah

Appointed: 1985, President Ronald Reagan

Education: BS, BYU, 1957; JD, University of Utah, 1960

Notable: In 2003 Judge Sam presided over the high-profile Olympic bribery case in Salt Lake City; the case ended when Judge Sam dismissed bribery, racketeering, fraud, and conspiracy charges against two former Olympic bid leaders.

Memories of BYU: Judge Sam arrived at BYU as a relatively new convert to the Church, and many of his religious experiences on campus were new. “I was just very impressed with the devotionals,” he says, “and I feel like many of those experiences sort of molded my life.”

Quote: Sam’s parents, born on the same day in the same Romanian town in 1894, came to the United States to escape World War I in Europe. His father worked in a steel mill in Gary, Ind. Given his family’s humble beginnings, one of the most memorable experiences of his life came on Aug. 2, 1985, he says. He was in his office at 9:15 a.m. when he received a telephone call from President Ronald Reagan. “To have a president of the United States call me on the phone and invite me to be a United States district judge was just something that was overwhelming,” he says.

Galen L. Fletcher (BA ’87), faculty services librarian in BYU’s J. Reuben Clark Law School, assisted with the research for this article.

web: Visit magazine.byu.edu/griffith to read the full text of Ed Carter’s interview with Thomas Griffith.

feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.