Ironically, a major goal of BYU’s 2019 China song-and-dance extravaganza was to help rebrand BYU to the Chinese as more than just a song-and-dance university. And so each show on the tour of BYU performing groups began with a video presentation outlining the breadth of BYU’s China ties. And they’re extensive: with study-abroad opportunities, faculty exchanges, Fulbright scholars, and Chinese official visits to campus (including every Chinese ambassador to the United States but one in the last 20 years), there’s a constant flow of interactions between BYU and China. Read about BYU’s varied China connections—from a study abroad going on 35 years to BYU’s leadership in the U.S. federal Chinese Flagship Program to the thousands of alumni retirees who have served at Chinese universities through the China Teachers Program.

Study Abroad

It’s like a second home for Matthew B. Christensen (BA ’88). Fresh off a mission to Hong Kong, he first found himself at Nanjing University in 1985 as part of BYU’s inaugural China study abroad. “That was life-changing in that it just really piqued my interest . . . in China and China-related things,” says Christensen, now a BYU Chinese professor and author of several books on China and and all things Chinese. And he’s returned thrice to Nanjing University to direct the well-honed study abroad.

“Almost every [BYU] college has some activity in China.” —Jeffrey Ringer

From a base at Nanjing University, where students in the program can take up to a year’s worth of Chinese-language credits, 15–25 participants each fall semester take in the culture and history of one of China’s most historic cities and travel by high-speed train to other locations around the country.

And these days, they’re not alone. “Whether they do it regularly or occasionally, almost every [BYU] college has some activity in China,” says BYU associate international vice president Jeffrey F. Ringer (BA ’84, MA ’86). The Marriott School sends eMBA students to Shanghai to observe the mechanics of the global economy. Budding educators student teach at a dual-language school in Guangzhou. Civil-engineering students study megastructures and infrastructures ancient and modern, from the Great Wall to China’s proliferating subway lines and skyscrapers. All told, BYU sends more students and faculty to China each year than to any other country, save the United Kingdom.

Chinese Flagship Program

It’s not something every college-educated native Chinese speaker can do. To get a superior rating on the Chinese Oral Proficiency Interview, you’ve got to carry on a half-hour conversation with a native proctor, discussing the ins-and-outs of a specialty subject, debating current events and ethical issues, and describing abstract concepts. Oh, and nail your idioms. And work in historical allusions. And classical poetry. “Not making it feel forced,” adds Nathan M. Jensen (’20), a BYU finance major who took the test—and got superior—in June.

Jensen spent two semesters last year with the Chinese Flagship Program, a U.S. Department of Defense–funded program that seeks to increase the nation’s capacity in Chinese. BYU, the inaugural Flagship school back in 2002, now manages a center at Nanjing University (separate from the BYU study-abroad program) that top Chinese students from BYU and 11 other U.S. universities feed into.

At Nanjing University, Flagship students take a semester of language and direct-enrollment courses in their subject matter—law, business, biology, you name it. “The goal is . . . to train them to function at a professional level within whatever discipline they’re studying,” says Christensen, who directs BYU’s Chinese Flagship Program. To that end, during their second semester, the students scatter across China to intern in firms where their skills—language and otherwise—are put to the test.

Jensen lived in Shanghai, where he worked for a British consulting group helping countries break into the Chinese market. His roommate, BYU premed student Daniel D. Dawson (’20), worked for a biotech company focused on reproductive health. The only requirement for the Flagship students is that they speak Chinese at least 80 percent of the time at their workplaces.

It’s all aimed at achieving the superior rating at the end of the experience—a mark Christensen says about 75 percent of BYU Flagship students have reached over more than 15 years. It’s a distinction that sets them up for a variety of international opportunities. “If they want to go into government service, their applications are put on the top of the pile,” says Christensen.

Dawson calls scoring superior a “cherry on the top” to what proved to be even more valuable—his personal growth and insights gained while immersed in a new culture.

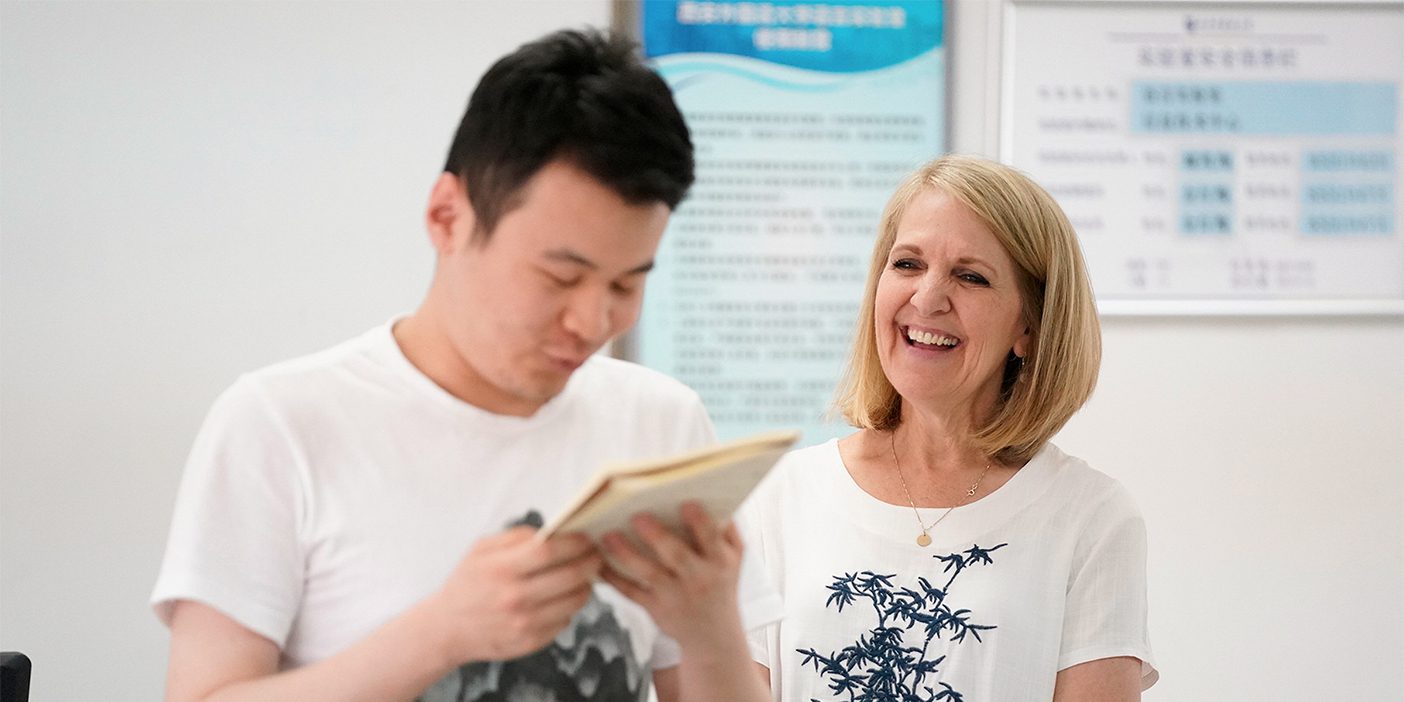

China Teachers

Special. Funny. Unusual. Fun. Kind. Patient. Very different.

Chinese college students use a lot of words to describe their teachers from the BYU China Teachers program, kindly retiree volunteers from the United States. But never normal.

Rigid and formal, “normal” teaching at Chinese universities involves a professor lecturing from behind a podium—often reading from the manual—and little participation from the students. Teachers rarely know the students’ names.

So it’s a pleasant shock when students at Peking University, China’s top school, first sit down in Brigg R. Steele’s (BS ’77, MEd ’80) business-English class and the retired international salesman spends time learning each of their names, backgrounds, and interests. Or when he tells them he thinks they’re the very best students in China. Or when, while teaching about business negotiation, he announces that he’s been negotiating with university officials for higher grades than normally allowed because his students are so exceptional and hard working. Or when he and his wife and fellow BYU China Teacher, Janet Allred Steele (BS ’81, JD ’90), invite them to their Beijing apartment for waffles.

“What I think comes across to the students is that I care for them,” says Brigg. And Janet says the feeling is mutual. “He always has a wait list. He always has full classes.” In her Academic Writing class, one of Brigg’s former students explained the demand: “He brings this light into the classroom because he loves us so much.”

Couples and individuals like the Steeles have been teaching at Chinese universities for 30 years, volunteering to teach English for an academic year. What began in 1989 with two dozen volunteers took off in the mid-1990s. “Those early teachers did such a fantastic job,” says Jeff Ringer, “we were very quickly in high demand.” Today, BYU China Teachers can be found in many of China’s top-10 universities. And many of the teachers now lecture in their specialties—such as law, medicine, or business.

“Grandma, I think you need to go back to China one more time, because they love Grandpa so much there.”

The “professional service opportunity” is one that BYU China Teachers say they’ll never forget—the adventure of encountering a new culture, the challenge of teaching at a university level, but mostly the interactions with their new friends, say Alan P. (MA ’87) and Kim Malan (BS ’00), former China Teachers who now coordinate the program. “That love that they feel for the students and the students feel for them is life changing.”

And it’s what drives most of the teachers to re-up for additional years—the Steeles had finished two and were considering a third when a granddaughter weighed in: “Grandma, I think you need to go back to China one more time, because they love Grandpa so much there.”

Web: Learn more about the BYU China Teachers Program at kennedy.byu.edu/chinateachers.