Despite battling hordes of rejections and criticisms, author Brandon Sanderson has garnered acclaim with his magical stories.

Adjunct BYU English instructor Brandon W. Sanderson (BA ’00, MA ’05) began his writing career behind the front desk of a Provo hotel. “It was pretty dead there from about midnight to 5, but they were required to have someone on staff,” he explains of his post-mission job. “And so when I got hired I told my boss, ‘I’m just going to write books all night,’ and he replied, ‘That’s great. At least you won’t sleep on the couch like the person before you.’”

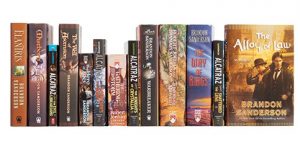

Squeezed between BYU homework and what little sleep he could muster, eight novels emerged over five years of Sanderson’s graveyard writing. “The first five were terrible,” he says. “I once heard that your first five books are generally bad, and so I determined I would write six at the very least.” Novel number six was Elantris, which sat on an editor’s desk at Tor Publishing for an agonizing 18 months before Sanderson got a response. Little did the haggard student know then that in a mere eight years, he would publish not only Elantris (in 2005) but 12 more novels, including his acclaimed Mistborn series and the middle-grade Alcatraz Versus the Evil Librarians series—as well as the final three books of The Wheel of Time, by epic-fantasy writer Robert Jordan.

When Jordan died of a rare blood disease in 2007, he left copious notes for concluding his renowned Wheel of Time series to Harriet McDougal Rigney, his wife and editor. Rigney searched for an author to finish her husband’s work and chose Sanderson after reading a heartfelt eulogy to Jordan from Sanderson’s blog as well as his first Mistborn book.

“The beautiful eulogy he wrote made me see the necessity of checking out his stuff,” says Rigney. “Brandon’s world—his characters and their situation—were all very clear to me. I saw that he could do it.”

“Robert Jordan had this beautiful way of looking through someone’s eyes, that when you were reading their viewpoint, you felt like you knew them,” Sanderson says. “As an early writer, I would study that and say, ‘How is he doing this?’”

Five years and more than 4,000 manuscript pages later, Sanderson marvels at the impact The Wheel of Time has had on his life. “It’s been an amazing, exhausting experience,” he says. Sanderson topped the New York Times Best Sellers list with his first two Wheel of Time installments. Spanning 20 years and 14 books, the Wheel spun to its highly anticipated finale when Sanderson’s A Memory of Light hit shelves in January 2013.

Brandon Sanderson fills a bookshelf all by himself, and one more novel—his 14th in eight years—debuted in January. A Memory of Light will likely be his seventh New York Times Best Seller.

“Brandon has a grand professional attitude, putting ego aside for the sake of the book,” Rigney says. “And the talent! His storytelling gifts are enormous, of the first magnitude.”

Although he is now a six-time best-selling author known for creating relatable characters, vivid settings, and unique magic systems, Sanderson was not a bred-in-the-womb writer. Like many adolescent boys, he avoided reading. But when his eighth-grade teacher convinced him to pick a book off her shelf, he chose Dragonsbane, by Barbara Hambly—because of its cool dragon cover. “It was like the story of my mom, except in a fantasy world with dragons, and that was just awesome,” Sanderson says. “It had all the action and adventure, and it had all the relate-ability.”

Sanderson went on to read every fantasy book in his high school. “Fantasy gives us this imagination, this power, this wonder, alongside real human problems, and it mixes all these things together in a package that is fun and readable and interesting,” he explains. “It grabbed me, and that’s when I decided I was going to be a fantasy writer—and I started writing.”

Initially a biochemistry major at BYU, Sanderson served a mission in Korea, where his mission president allowed him to write stories on preparation day.

“The most inspiring facet of Brandon and his work is that he understands thoroughly and profoundly how much writing is just that: work,” says Ethan M. Sproat (BA ’02, MA ’08), a PhD candidate at Purdue who worked with Sanderson on BYU’s student-run science fiction and fantasy magazine, The Leading Edge.

Sanderson returned to BYU, changed his major to English, wrote a bunch of novels, got a host of rejection letters, applied for grad school (twice), and got rejected from just about every top writing program in the States—except BYU.

Again and again Sanderson was told that his books would never sell because they were too long or too moral. But he was determined. “At the end of the day if you told me, ‘You will never get published,’ I would have still written the books,” he says. Halfway through his master’s program, he started work on The Way of Kings, which, he says, “I planned to be bigger and full of all the nobility and awesomeness that I wanted to see in epic fantasy. It was flying in the face of what everyone had told me. I wrote the biggest, coolest, epic-est book I could.” Between working on The Wheel of Time and his other novels, Sanderson eventually finished the 1,007-pager, which debuted at no. 7 on the New York Times Best Sellers list in 2010 and begins the anticipated 10-book saga The Stormlight Archive.

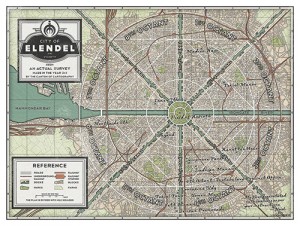

Known for creating magic systems and fantasy worlds—complete with intricate maps like this one for The Alloy of Law—Sanderson was tapped to complete the epic fantasy series Wheel of Time after the series author died in 2007.

Although Sanderson has emerged as a powerhouse in the genre, he always speaks of his success as a gift. “There are a lot of writers who are better than I am who are not successful,” he says. “It’s a measure of luck, perseverance, and providence.”

Perseverance in particular is a virtue he teaches to aspiring writers—both in his BYU fantasy and sci-fi writing class and in Writing Excuses, the weekly writing-advice podcast he cohosts. “Sit in a chair and write,” Sanderson says. “Ignore this thing they call writer’s block. Doctors don’t get doctor’s block; your mechanic doesn’t get mechanic’s block. If you want to write great stories, learn to write when you don’t feel like it. You have to write it poorly before you can write it well. So just be willing to write bad stories in order to learn to become better.”

One of Sanderson’s first students, new author Janci Patterson Olds (BA ’05, MA ’08), took Sanderson’s lessons of tenacity to heart. “Brandon really believes that anyone who’s willing to work hard can succeed,” she says, “which makes him a fantastic teacher and writing mentor.”

For Sanderson, creating worlds is all in a day’s work. “I love this job,” says the father of three. “You get up and do something different every day: you become a different character, you work on a different problem, you create something new. There’s nothing as supremely satisfying to me as looking at nothing . . . and at the end having something—a story, this thing that is almost alive.”

— Krista Holmes Hanby (BA ’11)