By Grant R. Madsen

You can’t find any classrooms on the 12th floor of the Spencer W. Kimball Tower, but serious learning is still taking place there.

You can’t find any classrooms on the 12th floor of the Spencer W. Kimball Tower, but serious learning is still taking place there.

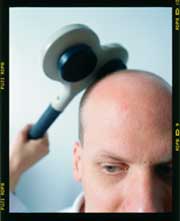

Inside the newly remodeled Brain Instrumentation Laboratory, undergraduate psychology student Brian J. Higginbotham lifts a “transcranial magnetic stimulator”—a hand-held instrument that looks like rubber-coated Mickey Mouse ears stuck atop a magic wand—and gets ready to research.

The stimulator, a key component in Higginbotham’s study on treating serious clinical depression, creates a magnetic field that is supposed to “realign” disrupted regions of the brain to a normal state. Already being used in parts of Europe, the treatment has not been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. That’s why Higginbotham, garbed in a white lab coat, is trying to determine if the stimulator really does what it claims to do and if it’s safe for humans.

“Will this method one day be the way people fight depression? Who knows? It could be the treatment of the century, or it could be forgotten in 10 years,” says Higginbotham, a native of Monterey, Calif. “If I discover something significant, great. If not, I’ll still feel like this whole thing has been worthwhile.”

And BYU administrators agree. In December 1999, the school’s Office of Research and Creative Activities (ORCA) awarded 238 undergraduate students $1,000 scholarships to fund research projects and other academic ventures. Proposals for money—557 in total—came from almost every department on campus. Although sources other than the ORCA scholarship fund undergraduate research on campus, the program is a catalyst for research by a large number of students who otherwise may not have a chance to participate in such projects. Along the way, some students uncover quality findings that may someday lead to changes in people’s lives. Recently, ORCA funded studies that examine Utah’s ban on public smoking, the impact that leaping in Irish dance has on a dancer’s shins, the factors that influence a woman’s choice to nurse her baby, and the coping responses of siblings of children with disabilities. As these examples suggest, asking students to come up with ideas for viable research projects causes them to stretch their minds as they seek to define the unknown and open new doors of understanding. And that, says Higginbotham, is important not only to him as a current BYU student, but to those who come after him.

Although sources other than the ORCA scholarship fund undergraduate research on campus, the program is a catalyst for research by a large number of students who otherwise may not have a chance to participate in such projects. Along the way, some students uncover quality findings that may someday lead to changes in people’s lives. Recently, ORCA funded studies that examine Utah’s ban on public smoking, the impact that leaping in Irish dance has on a dancer’s shins, the factors that influence a woman’s choice to nurse her baby, and the coping responses of siblings of children with disabilities. As these examples suggest, asking students to come up with ideas for viable research projects causes them to stretch their minds as they seek to define the unknown and open new doors of understanding. And that, says Higginbotham, is important not only to him as a current BYU student, but to those who come after him.

“The only reason we know the things we know today is someone made the effort to research and learn them yesterday. A big part of researching is sharing your knowledge with other people. In essence, you’re paving the way for future learning,” says Higginbotham, adding that research is, in that sense, a service to humankind. “The whole point of research is to enrich the human experience, to help people have happier, healthier, and more enjoyable lives,” he says, his eyes widening. “You can’t help but catch fire when you find something unusual or novel—you just have to get excited.”

Igniting a Spark

In undergraduates like Higginbotham, who completed his degree in April 2000, research ignites a spark for learning that leads them to further research and study. “I look forward to doing this kind of thing for the rest of my life,” he says.

Melvin J. Carr, associate director of ORCA and coordinator of the student scholarship program, says that setting aside such a large amount of money to kindle that spark is unconventional among universities of BYU‘s size. While most other universities encourage professorial and graduate-level research, few schools target funds for undergraduates. “But it’s such an important educational element that more universities are taking notice,” says Carr. “I’ve recently been approached by people at Northeastern University, George Mason University, and New York University asking me to explain how we do things here.”

Elaine Hoagland is the national executive officer of the Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR), an organization in Washington, D.C., that helps strengthen and promote research programs in predominantly undergraduate institutions. She says a scholarship program like the one BYU offers is the exception, not the rule.

“I’ve worked with CUR for three years, and have been in the industry for 13,” says Hoagland, whose office serves 3,500 members representing more than 850 institutions in eight academic divisions. “And I’ve never heard of a university providing this type of scholarship. However, I know there’s a movement to try to do more of this type of thing.”

And, financially speaking, it’s a movement that students appreciate. April 2000 graduate Scott L. Stephens is a former exercise physiology major from Bartlesville, Okla., and a green belt in the martial art of ryute renmei. He couldn’t have done his karate experiment, which tested the strength of two types of punches, without the university’s funding.

“I was really grateful for the ORCA money. It allowed me to build all the equipment I needed for the experiment and freed up my time so I could focus on what I was trying to find out,” says Stephens, who is beginning medical school at Oklahoma State University this fall. “It paid for a really great learning experience.”

As part of his experiment, Stephens invited 30 Utah Valley karate disciples from rival martial arts schools to take their best shot at a metal force plate that measured the amount of pressure applied to it. With colorful cloth belts tied around their white uniforms, subjects delivered punishing blows into the padded plate while computer sensors collected information for Stephens to analyze. The information from the “punch off” may someday be used to help people training for martial arts competitions develop better attack strategies. Stephens also sees a possible application for athletic gear manufacturers in developing better protective sparring equipment.

Medical school interviewers were impressed with the fact he had done research as an undergraduate, says Stephens—so much so that they offered to pay for his PhD in biomechanical research while he earns a medical degree. “I’m really excited to be able to continue research of the martial arts when I leave BYU,” says Stephens.

Funding Ideas

The big push to make undergraduate research a priority at BYU came in 1993, when Gary R. Hooper, now associate academic vice president for research and graduate studies, created the $1,000 scholarships. As a BYU undergraduate in the 1960s, Hooper was given the rare chance to conduct funded research. Upon returning to the university as an administrator, he wanted students to have a similar learning experience. Since its inception the ORCA scholarship program has funded 924 proposals, paying out close to $1 million. “Doing research was one of the highlights of my time at the university—it helped me see that learning isn’t just confined to the classroom,” Hooper says. “What we’ve seen over the years is that BYU students really enjoy working alongside their professors. The ORCA scholarships galvanize the administration, faculty, and students into having a learning experience with a real student focus.”

“Doing research was one of the highlights of my time at the university—it helped me see that learning isn’t just confined to the classroom,” Hooper says. “What we’ve seen over the years is that BYU students really enjoy working alongside their professors. The ORCA scholarships galvanize the administration, faculty, and students into having a learning experience with a real student focus.”

To be awarded ORCA funding, students are required to counsel with a faculty advisor and write a research proposal. When submitted, this proposal is reviewed by the student’s department to determine if the pursuit is worthwhile. Some proposals receive additional review from outside their colleges before any cash is awarded. Only the best proposals receive funding, but a record number of applicants were awarded the scholarship in 1999.

One such applicant is Amy R. McGlashan, an art major from Clovis, Calif., who found herself up to her elbows in watercolor paints after returning from Scotland. Her project is based on the works of Scottish poet and songwriter Robert Burns (1759–1796), whom McGlashan learned about while serving a mission for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in southern England. “One day my companion and I met an old English man named David Davies who sang ballads for money on the high streets of Canterbury. The songs were touching and the words were descriptive. He told me that his lyrics were originally written by the comedians and old bards of Scotland—particularly by Burns, who’s famous for his descriptions of the Scottish landscape,” she says.

“One day my companion and I met an old English man named David Davies who sang ballads for money on the high streets of Canterbury. The songs were touching and the words were descriptive. He told me that his lyrics were originally written by the comedians and old bards of Scotland—particularly by Burns, who’s famous for his descriptions of the Scottish landscape,” she says.

From her encounter with Davies, McGlashan later came up with the idea of traveling to Scotland to paint and experience firsthand the scenes that Burns described in his poetry. “The idea was to connect me to Burns’ work and allow me to personally react to it. I wanted to interpret place and content as a painter,” she says.

As part of her project, she conducted a study of Burns’ writing to determine which of the sites mentioned in his poetry to visit. Then, she traveled to the selected locations to sketch, photograph, and paint. After she finishes 20 paintings, she plans to chose 10 of her best pieces for exhibition in Scotland and California. She will present the artwork accompanied by contemporary interpretations of Burns’ music.

“I can honestly say that going to Scotland was one of the greatest experiences of my academic career. To be able to experience the beauties of the Scottish countryside was inspiring,” says McGlashan, who graduated in August 2000. “I was determined to go on the trip, and probably would have gone if I got the money or not. But it was a real blessing to get the ORCA scholarship. Financially, it made things so much easier.”

Ideas in Action

The ORCA office doesn’t tell students what to do with the money once it has been awarded and doesn’t ask how it is spent. Many use it for costs related to their projects, others use it to pay for their time, while others use it to pay their rent, says Carr. “We really don’t track how they spend it. Obviously, we prefer it help finance their research.”

Scholarships are always awarded in December, and ORCA asks the student researchers to submit a two-page report of their findings by August. Then the ORCA office publishes the reports in the Journal of Undergraduate Research and Creative Activities. Although the journal is not on the same level as a professional, peer-reviewed journal, it gives students the opportunity to include in their resumés that they’ve had a funded, published undergraduate research experience, says Carr, something few undergraduates can claim.

Sometimes, however, student projects don’t unfold the way they are initially envisioned, and researchers don’t get the results they expect. Mark J. Bishop, an April 2000 graduate in community health from Lindon, Utah, used his funding in 1998 to try to determine if peer support groups could help teenage smokers quit their habit. Bishop hypothesized that having young smokers meet together once a month for social activities would help them feel support from others like them. He even talked to the Utah County Health Department about his project, where one official told him that his treatment might be adopted if it proved to be effective.

“The plan was to follow up with these kids for six months, and see if the quit rate would go up,” says Bishop. “Because the county had a low success rate with its tobacco cessation program, they were willing to look at other options.”

At the conclusion of his experiment, teenage participants said the support groups seemed to make a difference, but Bishop was unable to determine if his results were statistically significant. “The problem with the study was that I had too small of a sample size. The quit rate did go up, and it was a good idea, but some improvements needed to be made in the study for me to say that, yes, this is something that really works,” says Bishop.

Even though his project didn’t turn out as planned, Bishop is still grateful for what he learned by participating in research. “The whole experience was invaluable and is opening other doors for me,” he says. “I was talking to a health sciences professor who told me he considered me a good candidate for a BYU graduate program because of my research experience.”

Although he has received other scholarships in the past, Bishop says the ORCA funding is the one that’s made the most difference in his education. “I feel like the ORCA experience was the best of my college career. If I could go back and tell students how to get a real education, I’d tell them to get some practical experience like the kind the ORCA scholarships provide,” he says.

Research as a Springboard

The scholarships can also impact people’s lives in other significant ways, says Carr. One evening as he was leaving his office, he noticed a female student standing nearby, reading the list of funded applicants. She was in tears.

“I thought, ‘Oh no, she didn’t get it and she was counting on the money,'” says Carr. “So I asked her if she was all right. She explained she was crying because she was happy—she’d been funded and was overcome with relief. She told me that she wouldn’t have been able to afford coming back to school for her last semester of classes if she hadn’t gotten the money.”

The student later went to graduate school, says Carr. “When things like that happen, it’s very rewarding, but I’ve seen it go the other way as well. I feel like crying sometimes, too. I wish we could provide funding for every student who took the time to submit a research proposal.”

Limited resources make that impossible at this point, but for those students who do receive funding, Carr agrees the ORCA scholarship makes a difference when they apply to graduate schools or for national fellowships.

“It pulls them out of the normal pool of applicants and sets them apart as someone with specific skills that schools and employers need and appreciate,” says Carr.

1998 BYU graduate Susan C. Bromley, of Eden Prairie, Minn., is one who found her ORCA scholarship experience helpful in the job hunt.

Bromley, who worked under the direction of associate professor Larry L. Howell in the university’s microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) laboratory, performed research that was of high enough quality to be published in an engineering research journal. Upon graduation, she was searching for employment in the Minneapolis area. In a job interview with an engineering company, the interviewer discovered that Bromley had experience with MEMS research. Because the company was just beginning work in the area, her interviewer sent her to speak with managers over that segment of the company. She was quickly offered a position as a MEMSresearcher, and the company is even paying for her graduate education at the University of Minnesota.

Howell says the ORCA scholarship is a great way to give students like Bromley an edge in the real world. “We have excellent students at this university, and we want them to be leaders as they leave here,” he says. “Students with research experience are more likely to attend graduate school and are better prepared to succeed after graduation.”

Take, for example, 1998 graduate Chris R. Kelsey, from Green River, Wyo., who performed ORCA-funded genetic research under assistant zoology professor Keith A. Crandall. Kelsey gained an honor that not many students—graduate or undergraduate—ever achieve: being listed as the principal author on a scholarly research paper. This achievement helped him gain acceptance into medical school at the University of Colorado and helped qualify him for a part-tuition scholarship.

Pleased with the way research experiences positively affect his students’ lives, Crandall sings the praises of an undergraduate scholarship program. “Students obviously get into the research more if they’re getting some reasonable financial benefit from it. And it’s a nice award to have behind you when you’re applying for medical school or graduate programs. What it says is ‘Look, this student is not only doing research but is doing it at a level that others recognize as something worth spending money on,'” he says.

And Crandall says that mentoring ORCA-funded students helps his chances of receiving funding on his research. “If I can show institutional support for student education, it makes it that much easier for me to get funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF). Part of the NSF‘s mission is preparing future scientists through education—it’s part of what they’re encouraging. When I write on a research proposal that BYU is shelling out almost a quarter of a million dollars each year on undergraduate research, that I belong to an institution that has the same values as the NSF, I think they’re more likely to give funding.”

In this and other ways, undergraduate research strengthens the university as a whole, says Carr. “Research plays a large part in assisting the university in its desire to become a world-class institution. If you think about it, you really can’t have that kind of an institution without world-class students. The ORCA scholarship goes a long way toward preparing that kind of a student to represent BYU and be successful in the world.”

Back in the Kimball Tower, Higginbotham agrees with the sentiment, saying preparation for the real world is why he and others come to BYU in the first place. “Research goes right to the core of understanding and teaches students things they would never learn in the classroom,” says Higginbotham, waving his magnetic wand through the air to emphasize his point. “There’s only so much you can learn in books, and I think students who don’t do research are missing out on an important aspect of education. Learning is a process, and anything that facilitates that process—like research—is incredibly important.”

These photographs are illustrations of research projects mentioned in the article. The people shown are models, and except for the transcranial magnetic stimulator shown in the first image, the props are not the actual objects referred to in the text.