A BYU team makes the Joseph Smith Translation manuscripts available for future scholarly work.

In 1994 Scott H. Faulring, ’83, could hardly imagine that an eight-week military trip to Texas would lead to a detailed study of a divinely revealed text. At the time, Faulring was an assistant professor for the Air Force ROTC and spent his off time working as a research historian on a documentary history of Oliver Cowdery for the Foundation of Ancient Research and Mormon Studies (FARMS).

Reporting for an Air Force training stint in the Lone Star State, Faulring arranged a few days of leave time for a trip to Independence, Mo., to examine documents in the archives of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS; now the Community of Christ). But Faulring’s intended quick trip set in motion a flurry of events that led to a decade-long study of the 446-page manuscript of Joseph Smith’s translation of the Bible (JST).

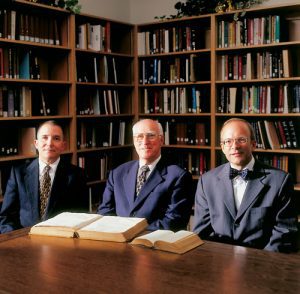

The result is a book to be published by BYU’s Religious Studies Center this fall, Joseph Smith’s New Translation of the Bible: Original Manuscripts. Edited by Faulring, professor of ancient scripture Kent P. Jackson, ’74, and professor emeritus of ancient scripture Robert J. Matthews, ’55, the bulk of the 851-page volume is a typographic transcription: a painstakingly created transcript of the original papers on which the JST was recorded.

While the book’s introductory essays are accessibly written, its primary intended audience is academics. The objective of the project was to reproduce as closely as possible the handwritten document in a typeset format. Since the transcription preserves original line endings, spelling, punctuation, strike-outs, and insertions, it’s not necessarily an easy read, says Jackson. “What it does do is give us access to the original manuscripts of the Joseph Smith Translation that we’ve never had before.”

Preserving Inspiration

Exploring the RLDS archives for examples of Oliver Cowdery’s scribal work, Faulring received permission in 1994 from the RLDS Church to view the pages of the JST for which Cowdery served as scribe. As Faulring leafed through a folder containing the manuscript’s first 10 pages, he noticed small bits of worn and brittle paper flaking off.

Returning to Independence in January 1995, he struck up a casual conversation with RLDS archivist Ronald Romig about the manuscript’s condition. When Faulring mentioned the possibility that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints archives in Salt Lake City might be willing to help with a restoration project, Romig immediately expressed interest. By the end of April that year, Faulring had gotten the RLDS Church, the Church of Jesus Christ, FARMS, and BYU to agree to a project proposal granting BYU’s Religious Studies Center (RSC) publishing rights for the entire manuscript in exchange for preservation work provided by the Church archives.

Faulring immediately set to work. Traveling to Independence at the beginning of May, he and FARMS photographer Steven W. Booras, ’68, spent two weeks at the RLDS archives photographing and scanning each page of the JST manuscript. After cropping, identifying, and compiling the images, Faulring and his wife, Barbara, spent the ensuing 18 months producing the first full draft transcription of the JST manuscript.

During this time Faulring called upon Matthews for help in providing historical and doctrinal context for the manuscripts. Matthews was the first Church member in modern times granted permission to view the manuscripts and also assisted Elder Bruce R. McConkie with the JST footnotes for the LDS King James Version of the Bible released in 1979. Over the years Matthews had visited Independence 22 times to view the manuscripts, and his early research laid the foundation for the new project.

While Faulring and Matthews worked, the Church archives completed the preservation work, fixing tears, removing tape, and reconnecting pages before microfilming the manuscripts and putting them in protective coverings.

About the time the manuscripts were returned to Independence, Faulring passed the baton to Jackson for the editorial work on the just-completed transcription. Viewing the scanned manuscript images at high resolution on a computer, Jackson and a team of students spent nearly every working day for more than three years refining Faulring’s transcription. They scrutinized the images line-by-line, letter-by-letter, comparing them with Faulring’s transcription.

“I felt very strongly early on that the Lord wanted this done and he wanted it done right,” Jackson says. “We’re dealing with the publication of revelation. There’s no doubt in my mind that the Lord opened the windows so that we could do this.”

The major difficulty for Jackson’s team was handwriting. The transcribers’ penmanship wasn’t always legible and they didn’t always spell well, Jackson says. “It would’ve been easier if we’d been attempting to produce an edited text with modern spelling. But because we were endeavoring to produce exactly the writing that was on the manuscript pages, we had to make decisions on every letter of handwriting.”

Also, to help readers understand the manuscripts, the book includes more than 900 photographs of verses from Joseph Smith’s Bible. During the translation process, which was completed July 2, 1833, Joseph Smith had two ways of dictating the changes: He either dictated the entire text, or he had his scribes write the book, chapter, and verse numbers with just the changed words. The Prophet then marked in his Bible where the correction was to be placed. The photos from the marked Bible show the insertion and deletion points, letting readers put the changes in context.

New Views of the JST

While their research doesn’t delve into the doctrinal realm, Faulring, Jackson, and Matthews say that it gives new historical information that’s never been published. For instance, while known scribes included Oliver Cowdery, John Whitmer, Sidney Rigdon, and Frederick G. Williams, it was previously unknown that Emma Smith had done some of the work. Faulring and Matthews noticed a subtle difference in handwriting while examining the manuscripts. They checked it against some of Emma Smith’s letters and found that for a little more than two pages, she had been the scribe.

And because of more accurate dating, the researchers have also been able to discover numerous instances of doctrinal changes that appeared in the JST before they were announced in the Doctrine and Covenants, although it was previously thought to be the other way around. While Matthews had earlier discovered a few instances of this, the current project provided other examples.

“The point that I can see that will be of great value is the relationship of the JST to the Doctrine and Covenants,” says Matthews. “It will be impossible to say how important that is.”

Later a CD-ROM with scanned manuscript images linked to the typographic transcription will be released; thus future researchers won’t have to get their hands on the real thing: they can just open their book or flip on their computer.

“The most important part of the JST is its content,” Matthews says. “But making it available in the original is a necessary foundation.”

“Most people in the Church who hear there’s going to be a book about the JST will think it’s going to be a doctrinal explanation, and it isn’t,” Matthews says. “But it’s going to be a very important historical explanation.”