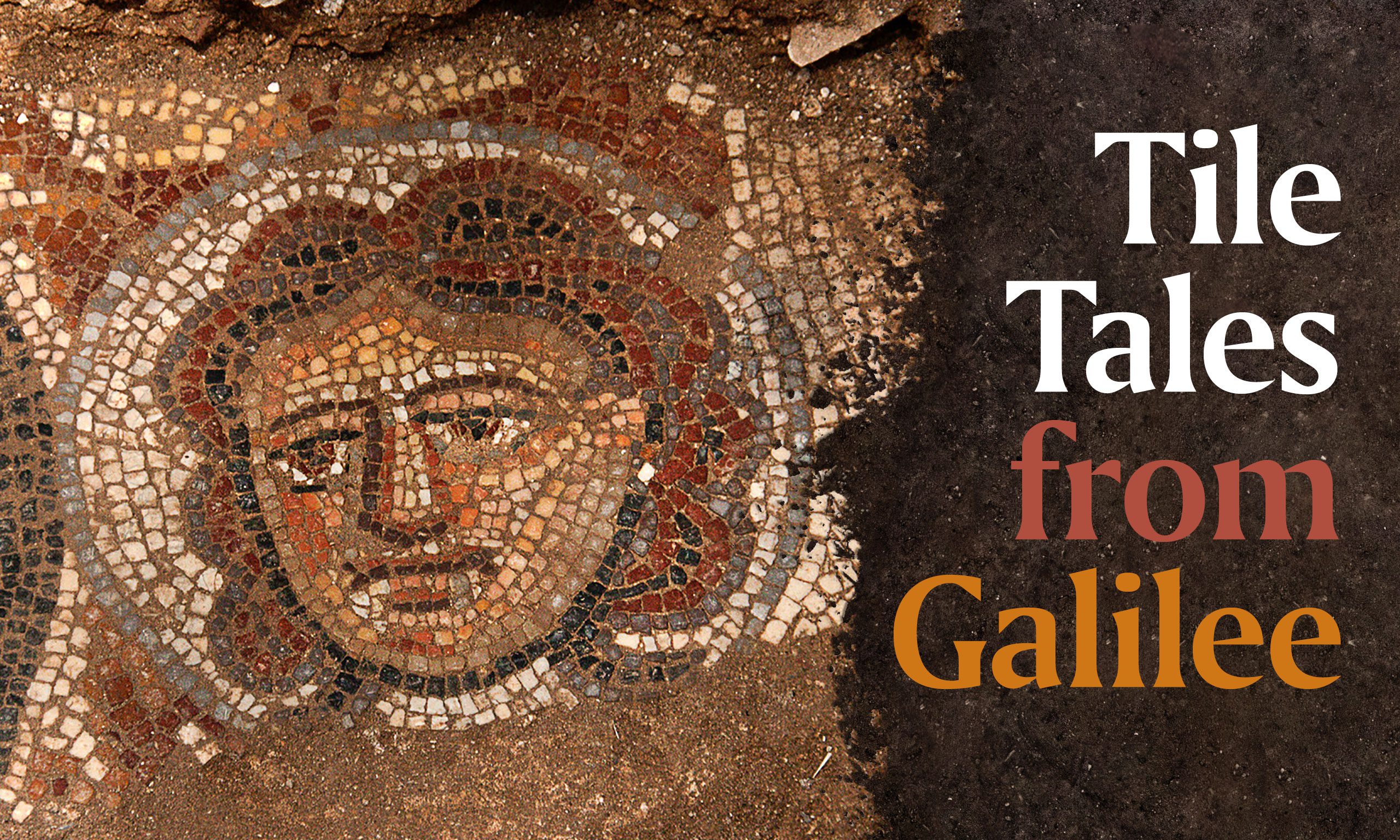

Tile Tales from Galilee

With a depiction of Jonah, the Tower of Babel, Noah’s ark, and other stories, a mosaic discovery by BYU researchers gives insight into ancient Jewish art and worship.

By Peter B. Gardner (BA ’98, MA ’04) in the Spring 2019 Issue

Photography by Jim Haberman

Words failing, he could only point a trembling finger. Moments before, wielding pickax and hoe, recent BYU grad Bryan R. Bozung (BS ’12) had been breaking up dirt in a pit at the site of an ancient Jewish synagogue in the Galilean village of Huqoq. That summer of 2012 he had joined a research team with the modest goal of uncovering data to improve Galilean synagogue dating.

But the nature of the project shifted dramatically the moment Bozung’s hoe scraped against something hard just below the surface. Through the clods “I could see the flat surface, some variation in color, and faint lines,” he remembers. He alerted the team lead, University of North Carolina archaeologist Jodi Magness, who used a paintbrush to reveal a woman looking back at them—exposed to the air for the first time in more than a millennium. “I was truly speechless,” says Bozung.

“We were not expecting . . . anything that sensational,” says BYU ancient scripture professor Matthew J. Grey (BA ’03), who had done doctoral work under Magness and was tasked with supervising the synagogue excavation. “All of a sudden we had this precious ancient art that needed to be excavated fully.” And to be shared with the world. Images of the fifth-century CE mosaics began popping up in news articles, archaeologists and antiquities officials journeyed to Huqoq to examine the site, and National Geographic provided additional funding.

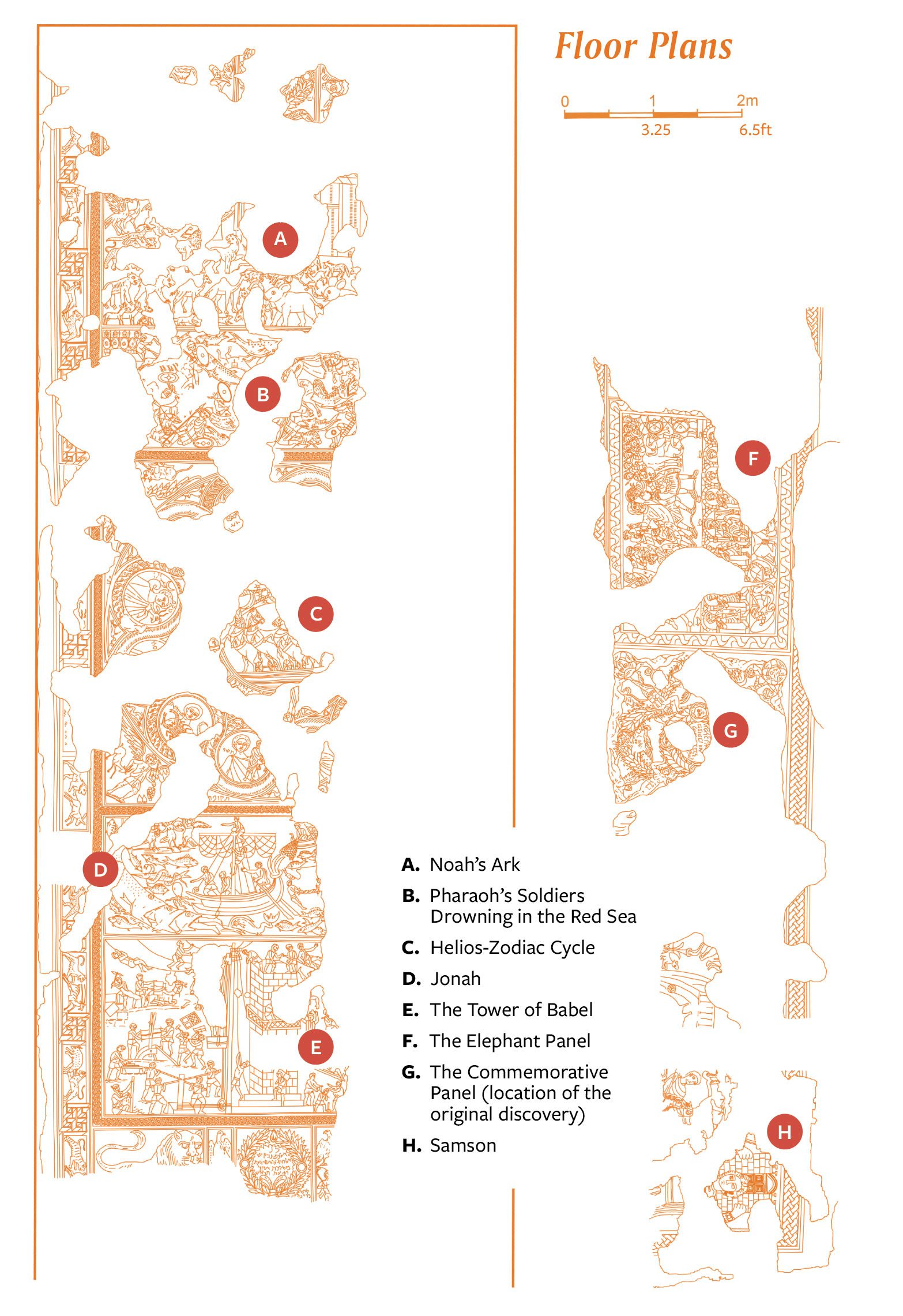

Finding mosaics was rare enough on its own—but during the following six years at Huqoq, the team uncovered a selection of scenes never found in an ancient synagogue in Israel: biblical depictions of Samson, Jonah, Noah’s ark, Pharaoh’s army swallowed up in the Red Sea; snapshots of daily life in antiquity; even an enigmatic non-biblical story.

And BYU students have been witness to it. With financial support from BYU’s Inspiring Learning Initiative and under the auspices of the Jerusalem Center for Near Eastern Studies, Grey began bringing groups of undergraduates in 2016 to get ancient dirt under their nails and watch the rewriting of history. Mark D. Ellison (BA ’90, MEd ’98), a BYU ancient-scripture professor and early-Christian-art expert who joined the BYU group in 2018, says, “It’s life changing for these students who get to go and do this. These are some of the most exciting discoveries of late-antique religious art in our lifetimes.”

“These are some of the most exciting discoveries of late-antique religious art in our lifetimes.” —Mark Ellison

Though heavily damaged, the Huqoq mosaics join with those found at select other sites in reframing our conception of ancient Jewish worship, say the researchers. From the surviving written record of this period, made up mainly of rabbinical literature based in the Torah and oral traditions, “most scholars had assumed that Judaism at this time was uniformly conservative in its religious beliefs and practices,” says Grey—meaning no figural art and certainly an avoidance of non-Hebrew influences. So “it was a little shocking,” he says, when synagogue mosaics were first discovered early in the 1930s replete with images of human, animal, and mythical figures; zodiac cycles; and Greco-Roman iconography blended into biblical stories.

Magness calls such elements an important corrective to the historical record, revealing a Judaism that was both “diverse and dynamic” during the Late Roman period.

“While they were still fully integrated within Jewish society,” adds Grey, “we now have evidence that some communities were more open than others to the Greco-Roman world around them.”

Far from depicting a Jewish community in decline during the rise of the Christian Byzantine Empire, the mosaics and other discoveries at Huqoq reveal a thriving community with vibrant religious and artistic traditions. And, says Grey, they provide evidence that “Jewish thinking and the Jewish community and Jewish worship were much more diverse than we once thought.”

The Jonah Panel

Jonah and the Whales: This unique depiction of Jonah is tied to a midrash, or scriptural commentary, circulating at the time the Huqoq mosaics were made, says Grey. Because the Hebrew text of the story includes three different variants of the word for fish, some readers interpreted this to mean that Jonah was swallowed by not one but three fishes in succession.

A Judeo-Christian Story? While the story of Jonah is common in Late Roman–era art, Ellison says it’s most often found in Christian funerary settings, where the story is a metaphor for death, resurrection, and eternal life. This is the first example of the Jonah story to turn up in an ancient Jewish worship setting.

That’s in the Bible? Don’t remember flute-and-lyre-playing harpies in the biblical story of Jonah? Grey says the half-bird, half-human creatures in the Huqoq mosaic serve as a visual shorthand for a sea storm: “That’s how storm winds had been portrayed in Greco-Roman mythology for many centuries.”

And he says it’s a clear indication that, for this community of worshippers at least, figures from Greco-Roman myths were not considered out of place for synagogue decor. The use of such images doesn’t necessarily indicate the incorporation of pagan beliefs, says Ellison. Rather, he says it may simply show that “religious communities had a rich cultural inheritance that they could draw from.”

Postcards from Galilee: Grey says this panel provides a priceless snapshot of ancient fishing practices. “You see sailing, see how they dress when they’re out to sea,” he says. “You see how the ship works,” how they would have climbed the mast, let down the sails, or used the rudder—all details ancient literature doesn’t normally reveal.

More to Uncover: Originally constructed in the early fifth century, the synagogue at Huqoq was replaced by a large public building centuries later in the medieval period. The renovation, along with later alterations, demolished many of the mosaics. “There was a lot of damage in antiquity,” says Grey, “but the amount that was preserved was just stunning.” The north and west aisles are still being excavated, conserved, and catalogued, the results of which will be published in coming years.

Sacred Orientation: The synagogue is oriented so that its front entrance points toward the Temple Mount in far-off Jerusalem.

Bridging Heaven and Earth: Scholars debate the religious significance of the mosaics found at Huqoq and the few other ancient synagogues that have yielded mosaics. While some see them as purely decorative, Grey and Ellison both suspect they had a ritual function. “You just don’t put that kind of expense into something that doesn’t have some meaning,” Ellison reasons. “It’s not just trendy decoration; there’s a reason to go to that trouble.”

At the very least, Ellison says the images, located in the place where worshippers read and commented on scripture and offered prayer, would “visually facilitate a connection between the past and that living community of faith.” And Grey proposes that the Huqoq synagogue’s distinctive selection of images—Jonah, the Tower of Babel, Noah’s ark, Samson, and others—all offer “displays of the power of the God of Israel.”

While unique, the Huqoq images align in one way with several other known synagogue mosaics: at the focal point—the middle panel of the central nave—is a Greek zodiac cycle. Huqoq’s zodiac is largely damaged, but one can still make out the central position of the sun god Helios, drawn by his four-horse chariot and surrounded by a ring of the 12 signs of the zodiac (some still intact), each personified and labeled with Hebrew month names.

For Grey the question remains: what is a Greek zodiac doing in a Jewish synagogue? His theory is that the circle-in-a-square motif of the zodiac panel might reflect the ancient conception of the firmament of the heavens as a dome resting on the four-cornered flat plane of the earth. Or, as Ellison puts it, “an artistic way of saying to worshippers, we’re now in a space that’s bridging heaven and earth.”

The Tower of Babel Panel

A Tower to Heaven: Several aspects of this mosaic point to the bible’s Tower of Babel story: the strongly vertical shape of the structure under construction, the variety of ethnicities depicted, and the signs of rising tension—workers fighting, another tumbling from the tower—in an otherwise orderly construction scene.

Tools of the Time: How do you build a monumental structure in the Late Roman period? “Well, they’re showing us,” says Grey. The panel depicts the quarrying of blocks, carpentry tools in use, a unique pulley system for hoisting blocks, even a measuring tool tucked behind a worker’s ear. “The ways in which this scene depicts various aspects of ancient daily life are extremely informative,” he says. Because technologies were slow to evolve in antiquity, the researchers say it’s not a stretch to assume that the scene might also well reflect practices from New Testament times, centuries earlier. “If you want to imagine Jesus and Joseph working in construction a few centuries earlier, it’s probably not going to look much different than what these workers are doing here,” says Grey.

The Elephant Panel

Lighted Lamps: Ellison sees parallels in the middle register to Christian arcades from the same period with Christ at the middle, flanked by the apostles. Where this Huqoq mosaic features an oil lamp above each of the figures’ heads, the Christian version would have featured a star or a laurel crown. “Using the visual strategies of the time,” says Ellison, the artist might have employed the lamps as “symbols of divine light, holiness, or eternal reward.”

Enigmatic Eta: What does the Greek letter eta on the robes of the priestly figures signify? An abbreviation? A symbol of status or honor? The experts don’t know, although similar Greek letters have been seen on clothing in other art from the period.

Four Theories: Some things about the “Elephant Panel” are clear. The bottom section, or register, reflects the aftermath of a bloody battle; the middle register shows Jewish priestly figures in a classical arcade; the same figures stand in the upper register, swords at the ready, opposite Greek troops accompanied by battle elephants. At the center is an encounter between a priestly figure and a military leader, who seems to be presenting a bull, perhaps to be sacrificed.

But just what actual encounter it depicts is anyone’s guess—and highly educated guesses have been made. Magness favors the legendary meeting around 332 BCE of the Jewish high priest with Alexander the Great, who fought with battle elephants, as told in the writings of Josephus. Two art historians called in to work on the project, the University of Louisville’s Karen Britt and Princeton’s Ra‘anan Boustan, point to another Josephus story, about a treaty formed between Seleucid ruler Antiochus VII Sidetes and high priest John Hyrcanus in the second century BCE. For his part, Grey thinks the art recalls a Jewish victory over Greek forces and venerates martyrs from the apocryphal book of Maccabees. Still other scholars see here a biblical scene: the prophet Samuel confronting Saul, dressed in Hellenistic garb, and his battlefield spoils.

And yet, “no one interpretation answers all the questions,” says Grey.

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.