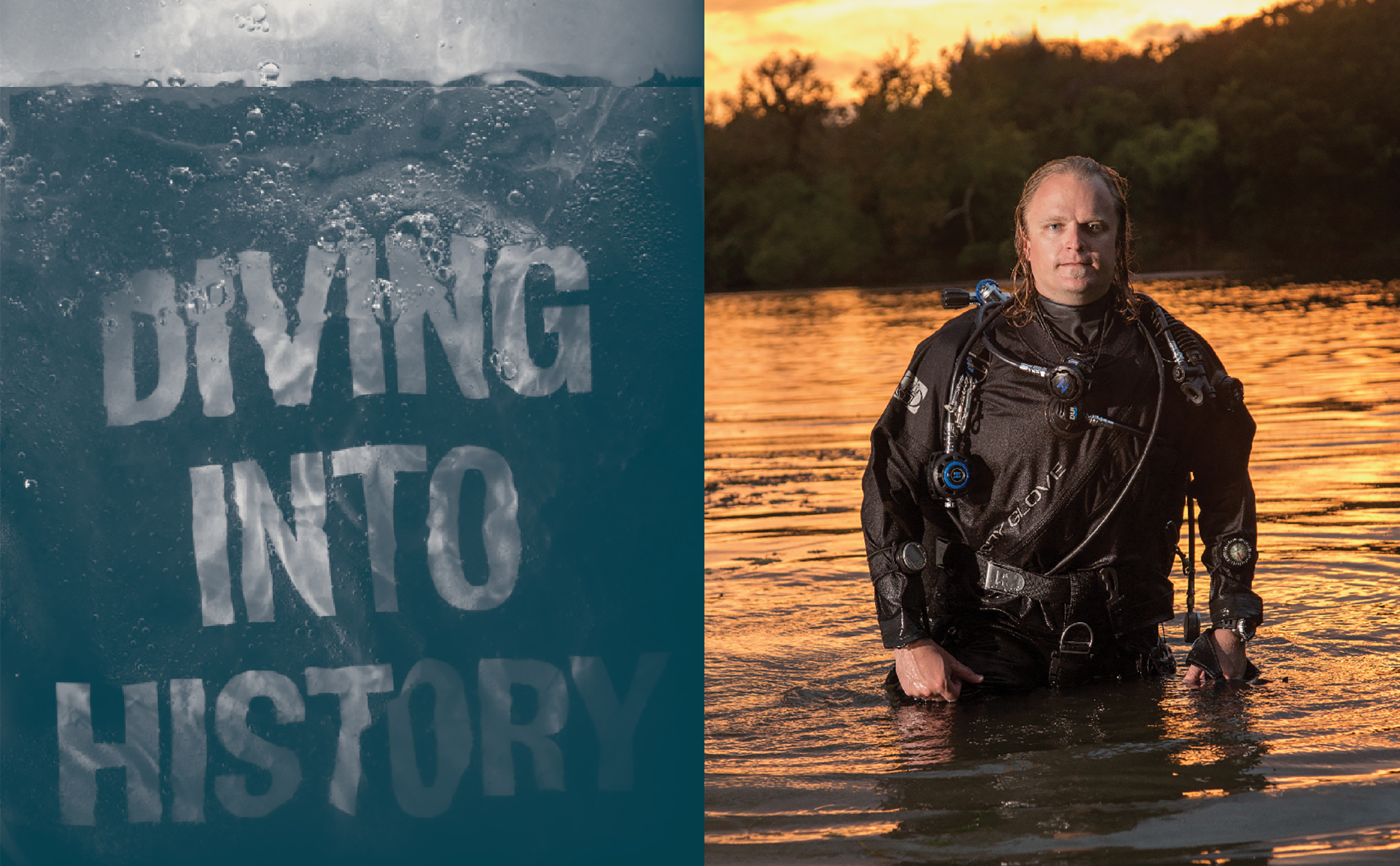

Diving into History

Diving into History

With the look of a pirate, the heart of an explorer, and the mind of a scientist, a BYU alum has followed his dreams to the bottom of the ocean.

By Charlene Renberg Winters in the Winter 2014 Issue

Photography by Mark A. Philbrick (BA ’75)

When the teacher of 5-year-old Eagan Hanselmann asked him about his summer vacation, he talked about living on a beach, swimming, snorkeling, and watching his dad retrieve cannons, anchors, and other artifacts from a pirate ship that had been resting on the ocean floor for hundreds of years.

Later, at a parent-teacher conference with Eagan’s parents, Lyndee and Fritz Hanselmann, the teacher noted their son’s active imagination and penchant for tall tales before asking them about themselves. When Fritz said he was an underwater archaeologist who had taken his family to live on a beach where they swam, snorkeled, and scuba dived to retrieve cannons and anchors from a pirate ship, her eyes widened. “So it’s really true?“ she asked.

Perhaps the teacher should have taken a closer look at Eagan’s dad before expressing her surprise. With shoulder-length fblond hair, matching soul patch, and a swimmer’s build, Frederick H. “Fritz” Hanselmann (BA ’03) has often drawn buccaneer comparisons.

Hanselmann does indeed have an unquenchable thirst for open seas and treasure, though not for gold, silver, or gems. As a research faculty member at Texas State University and the chief underwater archaeologist and diving-program director with the Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, Hanselmann has spent the better part of a decade exploring historic shipwrecks in Latin America, the Caribbean, and North America, usually leading the charge as the principal investigator. The real booty for Hanselmann is the history buried at the bottom of the sea and its potential to illuminate past human life, behaviors, and cultures.

Getting His Feet Wet

Hanselmann’s first splash in the world of high-profile shipwrecks came in 2007, when the doctoral student and lecturer from Indiana University learned that cannons had been found off the coast of the Dominican Republic’s Catalina Island, not far from La Romana, where Hanselmann and auniversity team happened to be conducting research.

A recreational diver had discovered the artifacts in pristine, shallow waters a mere 70 feet from the shoreline, and the researchers from Indiana were asked to take a look at it. One of the first divers on the scene, Hanselmann says the coral-encrusted cannons strewn across the ocean floor took his breath away. Under the tutelage of his mentor, Charles D. Beeker, director of the Office of Underwater Science and the Academic Diving Program at Indiana University, Hanselmann became the assistant project director and helped retrieve and study the artifacts. Among them, they discovered small pieces of charred wood, the remains of a shipwreck.

“It was fascinating enough to find a shipwreck from the golden age of piracy, and it was amazing to start on a site from scratch and see it through,” Hanselmann says. “ But it was even more intriguing when we could look at the extensive written documentation and test it against archaeological records.” The more the Indiana researchers examined the wreckage, the more they suspected it could be the remains of the lost Quedagh Merchant, which had been seized by Captain William Kidd near the turn of the 18th century.

Captain Kidd had abandoned the ship at Catalina Island in 1699 prior to fleeing to New England to try to clear his name of piracy. He represented himself as a privateer who had been commissioned by English lords to capture ships such as this Armenian vessel, which had been sailing under French protection. Others claimed he was a reprehensible pirate, as the ship had been captained by a British merchant. The incident became a scandal throughout the British Empire. Kidd was executed in 1701, and his body hung over the River Thames to serve as a warning against piracy.

“He transformed his good fortune of being the first scientist on the scene into a seminal career opportunity—one he’d been preparing for his whole life.”

When the news broke that Captain Kidd’s lost ship had been found, the story quickly went global, and Hanselmann was among those inundated with interview requests. Beeker and Hanselmann’s research was featured on the National Geographic Channel’s Expedition Week program “Shipwreck! Captain Kidd,” and their findings provided the basis of Hanselmann’s doctoral dissertation. He transformed his good fortune of being the first scientist on the scene into a seminal career opportunity—one he’d been preparing for his whole life.

“I was a swimmer by the time I was 3 and loved all things aquatic,” says Hanselmann. Even though he grew up in the Midwest, he spent his summers visiting his grandparents on Florida’s Gulf Coast, where Fritz would free dive and snorkel. His grandfather would fill old dress socks with golf balls and toss them into the ocean for Fritz to retrieve.

In school Hanselmann lifted weights and swam, but he was also a member of the book club. At night when his friends were watching The Simpsons, Fritz was either watching Jacques Cousteau reruns and other marine shows or reading, mostly history books.

His mother, Suzanne Hanselmann, saw this passion when Fritz learned Indiana history in the fourth grade. “He would come home and point out where the fourth-grade books were wrong about such things as where people died or where specific events took place,” she says. ldquo;He was a chain reader and had learned to use critical-reading skills.”

Fritz consumed stories from many time periods and especially treasured those about pre-Columbian civilizations and the conquest and colonization in the Western Hemisphere beginning in 1492. He also loved the underwater adventure novels of Clive Cussler, an amateur underwater archaeologist. When Fritz realized there was such a field as marine archaeology, he says, “it was kind of like, ‘Sign me up.’ ”

When Hanselmann arrived at BYU as a freshman, however, his thoughts were occupied with providing a living for a future family, and he prepared to use his deep, well-modulated voice as a broadcast journalist.

But he soon found himself wandering the BYU Bookstore looking for texts to satisfy his passions for history and water. When he stumbled upon an underwater-archaeology book, he purchased it, read it that night, and decided to add a beginning-level archaeology course as an elective.

The teacher was Ray T. Matheny (BS ’68, MA ’62), a professor Hanselmann knew by reputation. He had read Matheny’s September 1987 National Geographic feature about uncovering portions of El Mirador, a great Mayan city that had disappeared under the denseness of the Guatemalan jungle two millennia earlier. For his final paper Fritz wrote, fittingly, about Bronze Age shipwrecks in the Mediterranean.

After serving a mission to Nicaragua, Hanselmann returned to BYU fluent in Spanish and with a love for Latin America. He changed his major to international relations but continued taking classes in anthropology and archaeology until he either had to switch his major again or stop haunting the Department of Anthropology. Hanselmann took the plunge and changed his major to anthropology, found a mentor in Professor John P. Hawkins (BS ’70), and began to pursue a career in anthropology and underwater archaeology.

He just needed to break the news to his dad.

“My father, understandably, was concerned that I [would be able to] take care of a family with this career choice,” explains Hanselmann, by then married.

“Guilty as charged,” says Herbert Hanselmann. “I had looked at anthropology and archaeology more as interesting hobbies, but I was wrong. Fritz has made it so much more than that and has shown me how important it is to understand the past and see how it connects us throughout history.”

Years later, Lyndee Hanselmann understands that parental instinct. “I like to tell my sons they should be surgeons or dentists and then dive on the side,” she says. “But they, of course, don’t listen.”

“I like to tell my sons they should be surgeons or dentists and then dive on the side. But they, of course, don’t listen.”

“I’m going to be a diver like my dad,” announces 9-year-old Eagan. Anders, age 6, says the same.

Their interest is no surprise, as Hanselmann has worked hard to make sure his work includes his entire family. After one long summer without his wife and oldest son several years ago, he worried he might return from a dig and have his child wonder who he was. So he and Lyndee sat down and made a family rule. “If I’m going to be gone more than three or four weeks, the whole family comes along,” says Fritz. “If we don’t have enough money, then nobody goes. Luckily, I have worked at places that have been very supportive of this rule.”

Eagan and Anders are familiar figures to the other underwater archaeologists and scientists. The boys, affectionately dubbed “the savages” by some of their dad’s colleagues, now have multiple stamps in their passports.

Lyndee has also jumped in, learning to scuba dive. She often helps with backfilling the sites to keep marauders from getting to the areas until the researchers can return.

In 2012 Fritz and Lyndee took the savages to see the National Geographic–sponsored exhibit Treasures of the Earth at the Children’s Museum of Indianapolis. The hands-on exhibit features a reproduction of part of the Captain Kidd shipwreck and numerous artifacts. They explored old maps to see where the ship was last seen when it was burned and listened as their dad described where ocean currents might have taken the doomed vessel. After the boys explored a replica cannon pile and used measuring tapes to study “artifacts,” Anders looked up and yelled, “Hey, Dad, that guy looks just like you!” Sure enough, in a subtle nod to Hanselmann’s involvement in the dig, the exhibit creators had fitted the scuba diver mannequin floating above the shipwreck with a mane of flowing, blond hair.

The Pirate Scholar

Any day he can dive is a good day for Hanselmann. Descending into the water, he enters what he calls “inner space,” where sounds are muted but the eye-popping splendor of marine life, coral reefs, and geological formations is everywhere. And there is nothing like a shipwreck to add to the wonder.

The possibility of finding a shipwreck of the notorious Captain Henry Morgan, arguably history’s most famous privateer (or pirate, depending on which country you ask), especially intrigued Hanselmann.

His opportunity to look for the legendary captain’s ships came by chance while attending a professional conference in 2008 with Beeker. Also in attendance was James Delgado, then president of the Institute of Nautical Archaeology, who was looking for a reliable young archaeologist to participate on a project near the Isthmus of Panama. When he asked Beeker if he knew of such a person, the Indiana professor beckoned Hanselmann to join them. Delgado quizzed Hanselmann about Captain Henry Morgan and Panama then requested a résumé and a page or two detailing what Hanselmann could bring to the project. Delgado didn’t have to wait long. Hanselmann went to his hotel room and, within two hours, had completed Delgado’s request.

Hanselmann had read a biography on Morgan in grade school and remembered many details about Morgan’s life. Better still, he had just finished Peter Earle’s book The Sack of Panamá on the flight to that very conference.

Ten days later Hanselmann was en route to Panama to join Delgado in the first archaeological survey of the mouth of the Chagres River. There they’d search for remnants of 500 years of maritime history, including the final voyage of Christopher Columbus, the creation of the modern Panama Canal, and the loss of five of Morgan’s ships.

In 1671 Morgan, sailing on behalf of England, took 1,800 men to Panama on the largest pirate invasion in the history of the Caribbean. Five of his ships, including his flagship vessel, The Satisfaction, hit a reef on the Chagres and sank. Morgan reassigned his men to other ships and sacked Panama City for its riches, leaving it engulfed in flames.

As Hanselmann entered the same waters Morgan would have sailed, he felt a connection with the times of the legendary pirate. While Panamanians are familiar with the story of the infamous Morgan who destroyed Panama, no evidence of Morgan’s ships had ever been found in the water. Anticipation ran high that the water contained vital stories from the past.

“We crawled over the reef almost on our hands and knees and dropped into the deeper side of the shoreward side of the other reef,” Hanselmann says. “No words can describe how we felt when we saw 17th-century English cannons and swords consistent with those Morgan would have used.”

As they worked together at the site, Delgado found a good scientist and friend in Hanselmann, whom he had made coprincipal investigator.

“Fritz exceeded our expectations,” says Delgado. “He always exceeds our expectations. He is so balanced every step of the way. Not only is he very smart and a good learner, but he also has strong moral fiber. I call this exceptional man my brother, but I really consider him more like a son.”

Two years after beginning the dig, Delgado was appointed to be director of the Maritime Heritage Program for the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries in the U.S. Department of Commerce, and he made Hanselmann, by then with Texas State, the principal investigator.

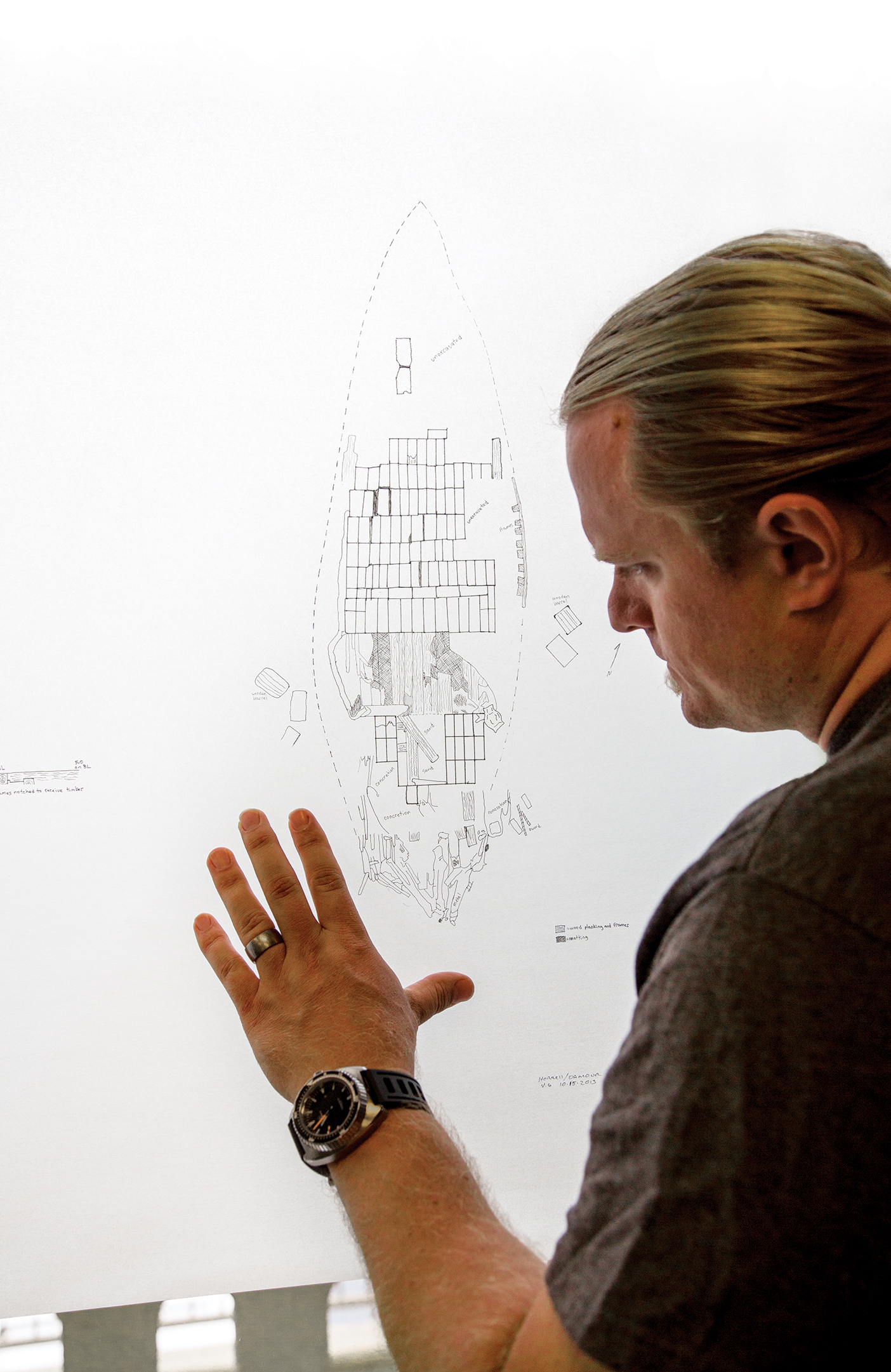

In 2011 Hanselmann and his team discovered a wooden-hulled shipwreck laden with wooden chests. They returned in 2012 to recover a sample of artifacts, such as a sword and a chest. Retrieving the more than 300-year-old artifacts without damaging them required care and creativity. The team built a sword-recovery case out of a plastic CD tower, a yoga mat, and rebar to secure it for ascent. To raise the chest and a wooden barrel, they used underwater lift bags and worked with industry experts to design special slings to wrap around the artifacts so they would hold together for the journey from the sea floor to the laboratory.

Hanselmann is very confident that the cannons they found belonged to Morgan. After their recovery from the sea floor, they were conserved in a laboratory and museum at the Patronato Panamá Viejo, and several pieces of evidence emerged.

Coralline concretions, rocks, and stones were removed and salts extracted to stabilize the artifacts. The scientists discerned inscriptions on some guns that indicate they are a mix of mid- to late-17th-century English and French. Morgan’s flagship, The Satisfaction, was originally French, and these fit the date range and origin. Hanselmann and his team hypothesize that these cannons were thrown off Morgan’s ships when they ran aground.

Like the Quedagh Merchant dig, the Morgan discovery made international headlines and was featured in a documentary, The Unsinkable Henry Morgan, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and can be seen on YouTube.

Hanselmann expected the filmmakers to use him for a day for an interview and some underwater shots while he recovered a wooden chest, but the director asked him to be present for the remainder of the shoot. Hanselmann would feature extensively in the film, which ends with the team electing him as the “captain” of the crew.

The choice to make Hanselmann a central part of the film may have had as much to do with his rich voice and buccaneer look as with his scientific credentials.

The long hair sort of emerged by accident. As a missionary, he received a horrible haircut and developed a phobia about having it cut in a foreign country. He trimmed it himself for the rest of his mission. During one early three-month dig away from his family, he did not want anyone to cut his hair and simply let it grow. When he returned home, Lyndee decided she liked the look and suggested he grow it even longer.

“It has become a signature style that sets him apart,” she says. And it makes Hanselmann stand out when he lectures for museums and other organizations.

“I tell Fritz to go ahead and be that pirate,” Delgado says, who himself maintains a close-shaved beard and wears a turtleneck and blazer that he used for his own sea-captain look when he hosted the television show The Sea Hunters for five years. “Fritz’s look does not detract from the reality that he is carving a serious niche as a responsible scholar.”

Andrew Sansom, one of Texas’s leading conservationists and Hanselmann’s supervisor at the Meadows Center at Texas State, compares Hanselmann—a teacher during the school year and adventurer during the summer—to Indiana Jones.

“He is kind of a rock star with genuine charisma,” says Sansom, “but he is graceful at deploying it.”

It was expected that the shipwreck near the cannons would be a Captain Morgan ship. Instead, as Hanselmann and his team studied the vessel, its materials, and the chests, they determined it was more likely a Spanish ship. The Spaniards figured heavily in the history of the region at the same time Morgan made his journeys.

Even so, the wreckage remains a significant historical find. And with the ship lying in only about 30 feet of water and featuring an intact hull, Hanselmann says it is a great location for a student field school and further in-depth study.

Hanselmann hopes to return to Panama, believing many more discoveries rest under the sea. “We have the guns, and the ship we found is from the Morgan era, so we can explore more about that time period. . . . We are right on Captain Morgan’s trail.”

Who We Are, Who We Were

Hanselmann went from diving in 35 to 40 feet of water to using a remote-operated vehicle in the summer of 2013 to explore three well-preserved shipwrecks resting almost a mile below the surface in the Gulf of Mexico.

As principal investigator of the so-called Monterrey Project, Hanselmann led a team of archaeologists, oceanographers, geologists, and biologists from three federal agencies, three universities, and three non-profit organizations. They set out to explore one ship, but they discovered two more within five miles of the first wreck. All three likely went down during the same violent storm in the early 19th century.

Delgado explains that this was an era when empires were falling, Spain was losing its grip on the region, France was selling what it had, Mexico and Latin America were becoming independent, and the United States was beginning to gain a foothold in the Gulf.

“We can be reasonably sure these wrecks are related to all that history,” Delgado says.

“The Monterrey Project blows me away,” says Hanselmann. “The ships are just a phenomenal sight.” He is accustomed to more hands-on work, but the setting allowed the team to see much-better-preserved artifacts and ships than are found in the warm, shallow waters where Hanselmann typically dives.

The team has recovered pearl ware; chargers; platters; plates; beer, rum, and wine bottles; medicine bottles; and two ginger bottles with their stoppers. Hanselmann is particularly intrigued by other diagnostic artifacts that may provide additional information about when these ships might have gone down, such as a date or a year. They can then check the historical records for ships that were lost at sea during the same time period.

As with all his explorations, Hanselmann looks for human connections and finds personal items especially touching. When ginger from bottles still smelled of the spice, he remembered that his mother would give him ginger ale and saltines whenever he had an upset stomach. He imagines that the ginger might have been similarly used by sailors during the storm that sank these ships. He also wonders whether a retrieved spoon might have been used to eat a last meal, and he finds poignancy in a leather shoe that went down with some unfortunate sailor during the shipwreck.

“It electrifies me to… understand how the lives of everyday people have been forever changed by their interactions with the sea.”

Hanselmann shared such insights—and the dig itself—with BYU archaeology professor Michael T. Searcy (MA ’05) and his students. Searcy and Hanselmann had become friends at BYU, and when Searcy learned about his friend’s Monterrey work through a Facebook post, he asked Hanselmann whether his students could observe the dig. Through a live video stream, Hanselmann responded to student questions, providing particulars about what the students were seeing, what might have happened, and when.

“It was absorbing, and my students observed field work as it happened,” Searcy says. “Nobody was surprised when I scrapped my lecture that day.”

The team went out with a lot of questions, and with just five days to dig at the site and explore the other ships, they returned with even more. The scientists have concluded that the ships were probably pirate vessels or privateers. Hanselmann hopes to secure sponsorship so they can continue the search this summer. To him it’s a library of culture with volumes still waiting to be read.

“It electrifies me to make connections with the past and begin to understand how the lives of everyday people have been forever changed by their interactions with the sea,” he says. That passion drives all his work, including his research into submerged Paleo-Indian and prehistoric deposits in springs and caves in Texas and Mexico and a project searching for colonial Spanish shipwrecks in Colombia. In each case, he sees his work as finding and sharing another part of the human story.

His blog posts, part of National Geographic’s Explorers Journal online, expound on his belief that such archaeological sites are part of a global heritage and still belong to the surrounding countries—in national museums or, better yet, left in place as marine protected areas or living museums. At the Quedagh Merchant site off Catalina Island, fish swim throughout the site, and endangered species of coral, attached to the remains of the 400-ton wreckage, continue to live in the warm Caribbean waters.

As a teacher and scientist, Hanselmann wants to make the past available and meaningful to present learners. He cites the sentiment expressed by John Quincy Adams’s character in the movie Amistad: “Who we are is who we were.” Underwater archaeology adds to that understanding and provides invaluable cultural context, says Hanselmann. “I love giving form to those stories.”