The most famous of the Inca ruins, Machu Picchu was built on the mist-swept Vilcanota Mountains nearly 1,800 feet above the steep Urumbamba River , which loops around three sides of the site.

By Nathan K. Chai, ’02, Editorial Intern

There is a power still in these stones, old enough now to speak intimately of centuries. Like testaments, they stand over a Peruvian high country whose beauties are fiercely sublime, over a Polynesian island whose people no longer remember why. Even in the pronouncement of their names one can feel the weight of their history: Suqsayhuamán. Machu Picchu. Moai.

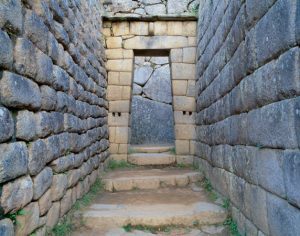

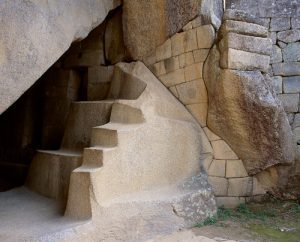

Today, empty corridors and buildings stand as witness to the Inca’s masterful stonework. At the entrance to a small cave beneath the Temple of the Sun, the inca worked around existing stone, creating nearly flawless joints.

Chiseled and set by hands that long ago ceased to work, these monuments are remnants of an older time, pieces of stories forgotten or erased. Yet even in their decline they possess a sacredness that defies the noise of modernity clamoring around them. It is this sacredness, this quiet persistence of the stone, that inspired BYU associate professor of photography Val W. Brinkerhoff, ’80, to a sort of pilgrimage, a pictorial exploration of these monuments and others like them around the world.

The project was inspired in part by the vulnerability of the monuments. As always erosion continues to gnaw at the stone, but now several new forces pose serious threats: vandals scrape names in many languages into temple walls; thousands of feet tread daily over the stone; urban and commercial developments vie for nearby real estate.

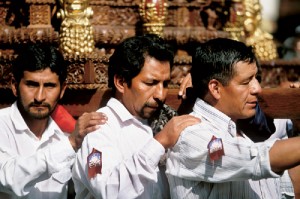

But there is another reason for the project, one more specific to BYU. Working with colleagues at ISPART (the Institute for the Study and Preservation of Ancient Religious Texts) and on his own, Brinkerhoff is photographing symbols of ancient temple worship for a visual database. With trips already completed to sites in Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, Brinkerhoff recently set out again, this time to explore the previously mentioned monuments in Peru and on Easter Island. Funded by a BYU mentoring grant, two photography students, Christopher R. Parkinson, ’02, and Matthew G. Turley, ’04, accompanied him. Their respective assignments were to shoot landscapes and portraits of the local people that would complement and provide a context for Brinkerhoff’s work on the monuments themselves.

Though it has been centuries since the agricultural terraces beneath Machu Picchu produced any crops, Inca culture still influences Peruvian life.

Suqsayhuamán

The trip began on the high Peruvian plains in Cuzco, which sits 11,000 feet above sea level and is built on foundations of the Inca capital of Qosco, meaning “navel of the world” in the Quechua tongue. Though the city was ransacked by gold-seeking Conquistadors nearly 500 years ago, much of the original stonework endures. The most famous of these ruins stands just outside the city proper at a place called Suqsayhuamán.

Here the Inca erected a religious and military site worthy of their civilization, fitting 100-ton stones together in perfect geometries, forming walls 400 meters long. Here also the empire fell into legend when Pizarro’s conquistadors trapped the survivors of Manco Inca’s army in three towers and let no one escape. Though much of the structure has long since crumbled, it is still one of the most powerful displays of Inca masonry anywhere.  “The architecture just feels more real,” explains Parkinson, who momentarily put aside his landscape work to shoot close-ups of the stone joints. “It seems to have more meaning, like it was made for a much greater reason than just economic gain. You feel that there’s a spirit to the place.”

“The architecture just feels more real,” explains Parkinson, who momentarily put aside his landscape work to shoot close-ups of the stone joints. “It seems to have more meaning, like it was made for a much greater reason than just economic gain. You feel that there’s a spirit to the place.”

As Brinkerhoff studied the ruins through his lens, he also felt a connection to the stonework of Suqsayhuamán. “These constructions are utilitarian as buildings, but they also enhance emotion through their strong visual presence. Like many ancient ceremonial structures around the globe, this architecture serves a dual function—it’s both practical and aesthetic.”

Leaving Suqsayhuamán and Cuzco, the photographers traveled by train deep into the Vilcanota mountains and the Urubamba River Valley, paralleling old Inca paths that modern pilgrims still travel, to the most famous of the Inca’s monuments—Machu Picchu.

Machu Picchu

It is said to have been many things—royal estate, sacred place of pilgrimage, temple site, military lookout, final refuge for Inca women during the Spanish invasion—but the true purpose for the citadel may never be known. Perhaps it is precisely this sense of enigma that makes Machu Picchu one of the most famous—and busiest—ruin sites in the world.

But even with the commotion of scores of tourists, the photographers felt a connection to the place—particularly in the morning, when the heavy mists climb out of the river valleys and hold the ruins in thick gray silence. On one of those early mornings, before the tour buses arrived, Turley climbed moss- covered stairways built by the Inca up the nearby peak of Huayna Picchu to where a small ancient temple still perches on the cliff tops. As day broke, he watched the mist rising like a dream from the ruins and pondered on the Inca’s motivations for creating such a place, theorizing, “The fact that they built this place in the mountains and that they built temples even higher reinforces a theme of ascension and nearing heaven.”

Parkinson and Brinkerhoff also spent the early mornings in solitude, listening to the water flow down the ancient channels, meditating on the history of the place.  “I often felt like just sitting and soaking in the incredible visual drama around me,” says Brinkerhoff of those early mornings. “I believe many modern-day visitors make pilgrimages to remote sites like Machu Picchu because there is a spiritual essence and peace about them, brought on by the beauty and majesty of skillfully carved stone nestled among the surrounding dramatic peaks. The beauty is rejuvenating and intoxicating.”

“I often felt like just sitting and soaking in the incredible visual drama around me,” says Brinkerhoff of those early mornings. “I believe many modern-day visitors make pilgrimages to remote sites like Machu Picchu because there is a spiritual essence and peace about them, brought on by the beauty and majesty of skillfully carved stone nestled among the surrounding dramatic peaks. The beauty is rejuvenating and intoxicating.”

Though the original inhabitants of Easter Island were almost entirely destroyed by the civil war and famine, their descendants persist among the current population of more than 2,000 people, including Rau (above), a fisherman who kills his catches by biting their heads.

Moai

More than 2,000 miles from any populated area, Easter Island is a place of isolation. Hundreds of years ago a small group of Polynesians, the only group in Oceania to develop a written language, settled the island. Their legacy—hundreds of massive stone statues called Moai—still fascinate scholars, who speculate that they were built to venerate the dead and that they provided a sacred link to the ancestors.

Though the photographers touched down on the island at night, the students went by flashlight to the beach, where they encountered a Moai for the first time.

“It was eerie,” Turley says of the experience. “It was so big that we couldn’t see the whole thing very well, even with the help of several flashlights.”

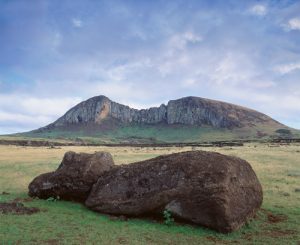

Easter Island is known for the monolithic Moai that stand watch over hillsides and coasts, The small island (about 63 square Miles) is characterized by a lack of trees and by extinct volcanos, including Rano Kau, the largest craters.

Over the following days Turley photographed the people of the island, who were among the friendliest he’d ever encountered. He spent an afternoon fishing with a dark, rough-looking man named Raú, who killed his catches by biting their heads until their bodies went limp; he ate a dinner of raw fish with a man he met while exploring the island on a four-wheeler; he had to decline an offer of a horseback tour after the raw fish presented a digestion problem.

In the meantime, Parkinson continued his work documenting the surrounding landscape. As the setting sun ended a long day of photography near a crater lake where the Moai were originally quarried and where several hundred unfinished works still wait, half-carved out of cliff walls or abandoned at the lakeshore, Parkinson took a moment to record his impressions of the place in his journal:

“It is incredible to see the craftsmanship of this civilization. They must have had a great respect for their dead to have built such . . . monuments, and their ancestry must have played a huge part in their lives.”

Sacred Places

After nearly a week on Easter Island, Brinkerhoff, Turley, and Parkinson returned home with more than 4,000 new photographs. The opportunity provided by the BYU mentoring grant had proven to be everything that the two students had hoped.

“I’ve had good photography classes,” Turley says, “but this trip wasn’t anything like a class. It was an experience.”  Parkinson adds that seeing the way Brinkerhoff seemed intuitively to know the importance of the monuments and how best to capture it on film helped him to achieve better results than he had before.

Parkinson adds that seeing the way Brinkerhoff seemed intuitively to know the importance of the monuments and how best to capture it on film helped him to achieve better results than he had before.

The mentoring grant, however, doesn’t just benefit students, as Brinkerhoff points out: “If you can match students’ talents and desires with project needs, you both win big as the synergy born of the marriage benefits all.”

The Moai, which on average weigh 14 tons, were carved out of rock walls at the Rano Raraku volcanic crater and then somehow moved to carious locations across the island. After a period of warfare, many of the Moai were abandoned at the Rano Raraku quarry or toppled from the ceremonial platforms

And as for the photographs themselves, Brinkerhoff plans to use the best of them—both his own and the students’—in a book on Easter Island and in his work with ISPART, hoping that the growing collection of images will increase understanding of the significance of ancient temple sites and other sacred places, both modern and ancient. He explains his goals further, stating that “these monuments, along with their varied symbolic motifs, hint at a common base for many world religions and showcase the similarities we share in ritual and belief rather than those things that divide us. Many of the ancient temples and other stone creations are like parables that serve to educate on different levels yet go unnoticed by many who choose not to truly see or understand them.”

FEEDBACK: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.