From season to season and coast to coast, opinions and labels change, but Danny Ainge remains the same.

Danny Ainge (BA ’92) has been called a lot of things. In fact, he has been in the public eye for so long and been so successful as an athlete; a coach; a sportscaster; and, today, as Boston Celtics general manager, Ainge has been called just about everything.

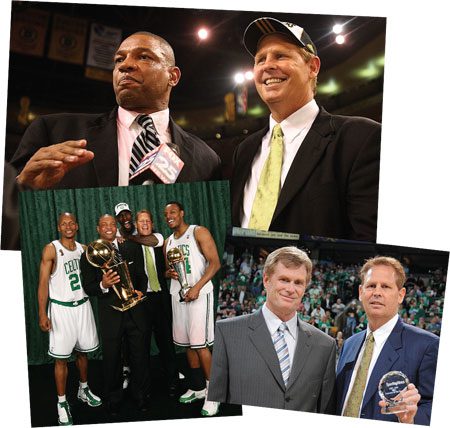

The 2007-08 season was unforgettable for Danny Ainge; Doc Rivers (left), the coach he hired; and the Celtics team he put together, including stars Ray Allen, Kevin Garnett, and Finals MVP Paul Pierce (lower left): the team won the NBA championships, and Ainge was named NBA Executive of the Year (right).

Disdain for Ainge and the annoying fact that his teams kept winning started building in high school as he led his basketball team to back-to-back Oregon state championships. Naturally, opposing teams found it hard to like the only high school athlete ever to be named a first-team All-American in football, baseball, and basketball. The negative feelings spread to opponents’ locker rooms and Western Athletic Conference arenas as Ainge became BYU’s all-time scoring leader—in the era before three-point lines—all while playing pro baseball for the Toronto Blue Jays.

Word of Ainge’s athleticism spread coast-to-coast his senior year as he and his Cougar teammates staged a comeback against a tough Notre Dame team in the NCAA Tournament. Down by one point with only 7 seconds left, Ainge dribbled the length of the court, somehow slipping past four defenders, then rolled a beautiful lay in off his fingers, just out of reach of Notre Dame’s tallest man. At the end of his college career, in 1981, Ainge received the John R. Wooden Award, given to the top college basketball player in the country.

Ainge played guard for 14 years in the NBA, winning two championships with the Celtics, in 1984 and 1986. He retired as one of only three NBA players to make more than 1,000 three-pointers and was said to be one of the league’s “most-booed players.” He did some TV work for TNT, then coached the Phoenix Suns to the playoffs three years straight. He would return to the Celtics in 2003 as general manager and later become president of basketball operations.

For four years every time Ainge drafted a player or made a trade, critics cried out, “What’s he thinking?” As Ainge adjusted the Celtics’ roster, doubters everywhere piled on unimaginative nicknames peppered with even less flattering adjectives.

But after the team that Ainge built went from winning just 24 regular-season games one year to 66 the next, the tone changed dramatically. The new name used most often to describe Ainge? Genius. Or, for variety, mastermind. And when space allowed: architect of the biggest single-season turnaround in NBA history.

For Ainge’s part in reviving the Celtics, Sporting News called him the NBA Executive of the Year. And the following fall, at a White House event, President Bush joined in, saying Ainge “knew what it meant to be a champion. After all, he’s from the 1986 championship team. And he knows there’s something special that needs to be put together to make a team work, and that’s Danny Ainge.”

The swings in sentiment bemuse Ainge’s wife, Michelle Toolson Ainge (’79). Before the comeback, Celtics fans would say her husband and the coach he hired, Doc Rivers, were responsible for all the Celtics’ woes. As soon as the team started winning, however, they were suddenly brilliant. In reality, Michelle says, all that had changed was public perception. “Danny is pretty much the same person, win or lose, good times or bad times,” she says. “This year they were successful; last year they weren’t. It doesn’t change him at all.”

While the Celtics had won a record 16 championships, including eight in a row in the ’60s, there hadn’t been a basketball title in Boston for more than two decades. The last banner was hung in the Garden in 1986, back when a younger, scrappier Danny Ainge was passing the ball to Larry Bird, Kevin McHale, and Robert Parish.

The 2007 Celtics finished the season with the second-worst record in the NBA (24–58). The team was rebuilding, working to draft well and develop young talent. But Boston fans were discouraged. After the second-worst season in Celtics history, the pressure, internal and external, was on for something to change.

Even Paul Pierce, the team’s top scorer, became discouraged and considered leaving. “He just wanted a chance to win,” says Ainge. “And he didn’t feel like we had surrounded him with the right pieces, which I completely agree with.”

The Celtics franchise and fans put their hopes in one more chance to change their luck. The team’s dismal record had earned them a shot at a first or second pick in the draft lottery. In the end, they drew the worst possible pick—fifth. “That was devastating to this whole area,” says local sportscaster Michael Dowling. “It really was.” The future looked bleak.

But Ainge was moving forward. First pick or fifth, he added that to his team’s cumulative assets. Then, says Dowling, “he went right to work.”

In June Ainge negotiated a trade with Seattle to bring one of the league’s purest shooters, 32-year-old Ray Allen, to Boston. With Allen and Pierce in his talent pool, Ainge then went after 11-time NBA All-Star power forward Kevin Garnett. Having played in Minnesota his entire career, Garnett wasn’t initially interested in changing uniforms. But Ainge persisted. “I couldn’t believe Danny kept calling him and flew out to his house,” says Michelle. “He had no shame the way he was chasing him. . . . He has no fear, and he’s a little bit crazy. Those two things have really helped him do some crazy things. And some of them really turn out.”

Ainge admits that chance played a role. “You have to be able to react when opportunities present themselves,” says Ainge. “I would say it’s a little bit of brains and a whole lot of luck.”

In the end, Ainge traded five young players, two first-round draft picks, and cash to get Garnett to play for Boston.

The Celtics started off the season with 18 straight wins, dispelling any concerns that this emerging team, with its new trio of stars, might need extra time to jell.

More than two decades ago, the Celtic’s original Big Three—Bird, Parish, and McHale—dominated professional basketball with consistency, aggression, and a sheer desire to win. In their long shadows dribbled a couple of guards.

“When I first got to the NBA, I thought I was pretty much a hotshot and I was going to tear the NBA up,” recalls Ainge. “One of my first games, Larry had the ball on the wing, and I made a slash to the basket. I thought I had an advantage on the post, so I stopped. Larry just looked at me and goes, ‘What are you doing? I have the ball right now. Get out of my way. This is my ball game.’ So then I did it again. At halftime, he started yelling at me like, ‘Get out of here! What are you doing? When I’ve got the ball on the wing, you stay over on the weak side. If your man leaves, I’ll find you.’ So I was humbled right away.”

To Bird, McHale, and the rest of the Celtics family, Ainge was the little brother. “I wanted to be as good as they were,” Ainge says, “and I wanted the same opportunities. But it became very clear that they were superior players, and I wasn’t going to get the first opportunities.” Yet, Ainge says, the team’s trust in him grew over time. “When I did well, they would be the first ones to congratulate and cheer me. But when things weren’t going well, they would be the first ones to tease and rub it in.”

While not the spotlight player, Ainge made his presence known on the court with pugnacious play. As in Ainge’s college days, his every emotion was visible. “When things didn’t go BYU’s way, displeasure was etched on Ainge’s boyish face,” noted an April 1981 Sports Illustrated story, which then quoted his mother, Kay Ainge: “All my boys are very facial, . . .and it has gotten them in trouble from time to time.” The Boston Celtics Encyclopedia puts it this way: “The baby-faced Ainge sported a youthful expression of innocence that worked to belie his fiery competitive spirit and near-violent intensity as one of the sport’s most combative warriors.”

Whether it was his facial reactions or his “near-violent intensity,” something about Ainge’s style united detractors among opposing fans. Ainge couldn’t have been more pleased. “One of the greatest compliments I received in my career was when crowds booed me on the road. People aren’t booing you if you’re no good,” he says. “There’s nothing better than being on the road and making a shot and just really making the opposing crowd angry. That’s the ultimate, that’s the peak of playing in sports.”

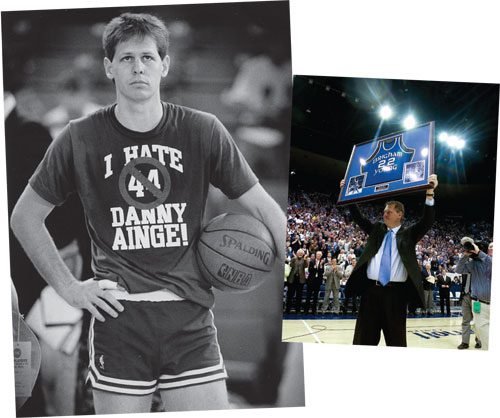

Before a playoff game in 1987, Ainge was warming up on the court. Up in the stands he spied a group of Pistons fans all wearing “I Hate Danny Ainge” T-shirts. Instead of taking offense, Ainge approached the fans and asked for a shirt. He wore the shirt throughout warm-ups, joining his detractors’ cause—“just having fun with the fans in Detroit,” as he puts it.

Beloved by home crowds, Danny Ainge faced – and reveled in – hostility whenever his team went on the road. He returned to an appreciative Marriott Center crowd in 2003, when BYU retired his jersey (right).

He was also able to deflect jibes from teammates about his lifestyle choices as a Latter-day Saint. Because Ainge didn’t go out and party with the guys, Kevin McHale once accused him of not having any fun.

“I just looked at him like he was crazy,” says Ainge, who replied: “You’ve got to be kidding me. I’m having the fun of my life. I’m living a dream. I have a beautiful young family. I’m playing in the NBA with the Boston Celtics. I mean, what could be more fun than that?”

In 1984 after he won his first NBA Championship, Ainge had as much fun as anyone when the corks popped. “They were all spraying champagne, and I had a can of orange soda and was drinking it and spraying it,” he recalls.

“The lifestyle of the NBA has done nothing but strengthen my testimony of principles of the gospel, such as that ‘wickedness never was happiness,’” says Ainge. “I witnessed firsthand that living in an almost Hollywood- or rock-star-type of atmosphere is the last thing that brings happiness. There’s no joy in the fun. As time went on, I think even my teammates recognized that I was having all the fun in the world.”

A DIFFERENT TITLE

Not long after the 2008 Finals, Ainge’s youngest daughter, Taylor Ainge Cannon (’07), wrote in her blog, “My dad was called to be the new bishop of our ward yesterday. He is such a busy man and is about to become much, much busier. And my poor mom has been looking forward to having her husband home again after the NBA Finals. I guess that is not going to be happening anymore. But despite the time and effort they are about to start putting into this ward, they are excited and eager to serve. It has been a great reminder of what great people my parents are and how blessed I am to have such great examples.”

Previously the first counselor in the bishopric, Ainge had anticipated some changes since the bishop had already served for five years. “But, honestly, there was no way they were going to call me, with my schedule, to be a bishop,” he says. “I had my doubts when they called me to be bishop, but I think that it will just compel me to find balance even more.”

“A lot of people are going to find out exactly how good of a guy he is and how much he cares about people,” says sportscaster Michael Dowling. “He’s our home teacher, and he really looks out for my boys . . . as a home teacher and a bishop would.”

FATHERLY PRIDE

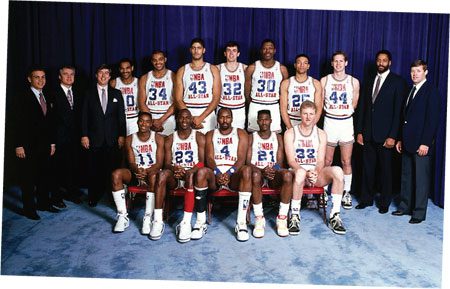

In the NBA Ainge (no. 44 above) played with the best, including members of the 1988 Eastern All-Star Team.

The Lakers and Celtics had met in the NBA Finals 10 times before. And while the heat generated by these league leaders had cooled over 20 years, during the 2008 NBA Finals, the rivalry exploded again, with chants of “Beat L.A.” carrying from TD Banknorth Garden to Paul Revere’s statue and the old North Church in Boston. It was just like the glory days: Celtics vs. Lakers.

The underdog Celtics took an early 2–1 lead in the series. In game four, on the road in Los Angeles, the Lakers led 35–14 after the first quarter. It was the biggest first-quarter deficit ever in a Finals game. Against the odds, the Celtics slowly worked their way back into the contest, eventually besting L.A. by six points to go up 3–1 in the best-of- seven series.

If there had been any question about who should be champion, it was answered in the final game in Boston. In the third quarter, with the Celtics up by 30 points, images of the Celtics owners and management were displayed on the giant video screen. The crowd cheered loudest for Ainge, but he wasn’t smiling—yet. In the end, the Celtics would beat their rivals 131–92—the largest margin of victory in an NBA Finals game—and become champions.

“It was just a storybook finish,” says Ainge. “For the pieces to come together like they did was one thing. But for the players to fight through some difficult times and make it all the way, and then for it to be the Lakers, and with the Lakers as such heavy favorites to beat us, and then to win in such convincing fashion—it couldn’t have been any better.”

In the end, Ainge felt a fatherly joy for the players. “Their lives kind of flashed before my eyes as I looked down the bench. I was smiling on behalf of each one of them.”

“It was more fun than being a player and winning it,” he says. “It really felt like it was my kids winning. I’ve scouted and drafted all these guys, counseled and had life discussions with them. It’s much more fun watching other people succeed.”

Left: Danny Ainge reads to grandsons Dre (left) and Oscar. Dre’s father, former BYU basketball standout Austin D. Ainge (BS ’07), works alongside Danny as a Celtics scout. Right: Ainge hugs his youngest daughter, Taylor, on her wedding day.

As the crowd of green-clad fans rushed the floor, Paul Pierce found Ainge, messed up his hair, and gave him a monster hug. “I think I was probably the most happy for him,” says Ainge. “He endured so much to get to this point and then stepped up his game to a whole other level in the playoffs. People could finally recognize Paul Pierce as the great player he’s always been.”

The moment of celebration is captured in a two-page Sports Illustrated photo, a wide shot of the crowded floor after the game. Players and fans are celebrating, and Pierce is holding up his Finals MVP trophy. Stage left, away from the spotlight, Ainge is visible only because he’s a head taller than the crowd around him.

As a man who has been called just about everything, Ainge had already become known as a championship player and now was a championship general manager. But as the fans celebrated the victory with his team, he was content to take a few steps back and let them enjoy their moment in the spotlight. It was their turn to make names for themselves.

By Michael R. Walker (BA ’90), Associate Editor

Feedback: Send comments on this article to magazine@byu.edu.

DANNY AINGE HIGHLIGHTS

Even before Boston won the 2008 NBA Championship, Celtics general manager Danny Ainge (BA ’92) had spent plenty of time in the national spotlight. See footage of his days at BYU and highlights from his NBA career.

Coast to Coast

1981 BYU vs. UCLA basketball game

This game can be viewed online at BYU Television. Once there, click on “Tune in Now.” After the video player loads, click on the tab that says “BYU Sports.” Click on “BYU Basketball,” scroll to the bottom, click on “1981 UCLA vs. BYU,” and enjoy the game.

NBA Champion—Again

A video clip detailing how Danny Ainge transformed a 24-win team into the league champion.