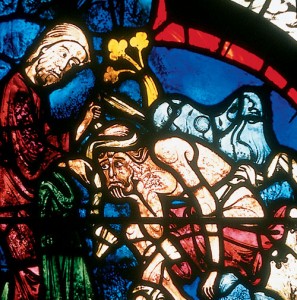

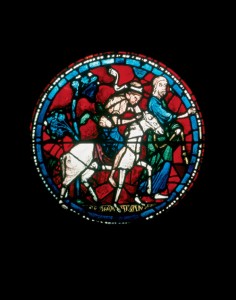

A Chartes, France, cathedral window depicts the good Samaritan leading the wounded traveler to an inn.

By John W. Welch, ‘70

One of the most influential stories told by Jesus is the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:30–35). As a result of this story, people all over the world speak of being a “good Samaritan,” or of doing good for people who are in need. And because we are all in serious need, especially of being spiritually rescued, this parable speaks deeply to every human soul.

The good Samaritan, as depicted in cathedrals in Chartres, Bourges, and Sens, France, exemplifies the redemptive power of Jesus Christ. The good Samaritan windows in these cathedrals juxtapose scenes from the parable against scenes from the fall and redemptive of mankind, thus pointing to a once-popular allegorical interpretation of the story.

Jesus told this parable to a lawyer, or a Pharisee, who began his exchange with Jesus by asking, “Master, what shall I do to inherit eternal life?” Jesus responded simply by saying, “What is written in the law? how readest thou?” The man answered by quoting two scriptures, the first from Deuteronomy 6:5, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thine heart,” and the second from Leviticus 19:18, “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” When Jesus promised, “This do, and thou shalt live,” the man challengingly retorted, “And who is my neighbour?” (Luke 10:25–29).

In answer to the man’s two questions, Jesus told the parable of the good Samaritan. We usually think of it as answering only the second, technical question, “Who is my neighbour?” But this story also addresses, even more deeply, the first and more important inquiry, “What shall I do to inherit eternal life?” The Prophet Joseph Smith once taught, “I have a key by which I understand the scriptures. I enquire, what was the question which drew out the answer, or caused Jesus to utter the parable?”1 Using the Pharisee’s primary question as such a key, with the second question being “like unto it” (Matt. 22:39), shows that the story speaks of eternal life and the plan of salvation in ways that few modern readers have ever paused to notice.

As dramatic as this parable’s plain practical content clearly is, a once time-honored but now almost-forgotten tradition sees this tale as teaching more than a lesson about helping those in need. According to that ancient view, this story is also an impressive allegory of the fall and redemption of all mankind. This revealing interpretation adds rich gospel dimensions to this well-loved parable.

The early Christian understanding of this allegorical interpretation of the good Samaritan is clearly depicted in the famous 12th-century cathedral in Chartres, France. One of its beautiful stained-glass windows depicts the story of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden at the top of the window and, at the bottom of the window, the familiar New Testament parable of the good Samaritan, “thereby illustrating a symbolic interpretation of Christ’s parable that was popular in the Middle Ages.”2 Even more explicitly allegorical windows are found in two other French cathedrals at Bourges and Sens. Seeing these windows led me to wonder: What does the parable of the good Samaritan have to do with the Fall of Adam and Eve? Where did this association of these scriptures originate?

Through research I soon discovered the answer.3 The roots of this allegorical interpretation reach deeply into the earliest Christian literature. Writing in the second century a.d., Irenaeus and Clement each saw the good Samaritan as symbolizing Christ saving the fallen victim from the wounds of sin. Origen, only a few years later, stated that this interpretation came down to him from “one of the elders,” who understood the elements of this story allegorically as follows:

The man who was going down is Adam. Jerusalem is paradise, and Jericho is the world. The robbers are hostile powers. The priest is the Law, the Levite is the prophets, and the Samaritan is Christ. The wounds are disobedience, the beast is the Lord’s body, the pandochium (that is, the stable [inn]), which accepts all [pan-] who wish to enter, is the Church. And further, the two denarii mean the Father and the Son. The manager of the stable is the head of the Church, to whom its care has been entrusted. And the fact that the Samaritan promises he will return represents the Savior’s second coming.4

This early text shows that the allegorical reading of the good Samaritan was known and taught by early followers of Jesus. The attribution of this interpretation to “one of the elders” strongly associates it with the earliest Christians.5 Moreover, this interpretation was virtually universal throughout early Christianity, being advocated by Irenaeus in southern France, Clement in Alexandria, Origen in Judea, Chrysostom in Constantinople, Ambrose in Milan, Augustine in Africa, Isidore in Spain, and Eligius in northern France, to name only a few.

A TYPE AND SHADOW OF THE PLAN OF SALVATION

Each element in this allegory corresponds significantly with an important step in the journey of all mankind toward eternal life. The parable of the good Samaritan is not only a story about a man who goes down to Jericho, but also about every person who comes down to walk upon this earth.

A certain man went down from Jerusalem to Jericho, and fell among thieves.

A certain man. The early Christian writers identified this man as Adam. This connection may have been more obvious in ancient languages than in modern translations. In Hebrew the word adam means “man,” “mankind,” or ” men,” as well as “Adam,” as a proper name.6 The Greek anthropos likewise can refer to all mankind as well as a particular individual. Thus, Clement rightly saw the victim in this allegory as referring to “all of us.” Latter-day Saints would agree. We are indeed all travelers, subject to the risks and vicissitudes of mortality.

Went down. Chrysostom saw this part of the story as representing the descent of Adam from paradise, the Garden of Eden, into this world—from glory to an absence of glory, from life to death. Indeed, Adam and Eve led the way for all of the human family, and their “going down” symbolizes the beneficial entry of all spirits into this world through birth.

The language in Luke 10 implies that the man goes down intentionally, through his own volition, knowing the risks involved in the journey. No one forces him to go down to Jericho. For whatever reason, the person apparently feels that the journey is worth the obvious risks of such travel, which were well known to all people in Jesus’ day.7 When the lone traveler then falls among the robbers, it is an expected part of the mortal experience.

From Jerusalem. The story depicts the person going down from Jerusalem, not from any ordinary city or place. Because of the sanctity of the Holy City, early Christian interpreters readily found significance in this element in the allegory, and Eligius said it represented “man’s high state of immortality.” Moreover the person comes down from a temple city, from the ritual presence of God, impliedly endowed with blessings and promises obtained from God. One of those assurances would have been that God would provide a Samaritan to save that person when he or she should encounter grave difficulty along the path of life.

To Jericho. The person in the story is on the road down to Jericho, which is readily identified as this world or, as Eligius said, “this miserable life.” The symbolism is fitting, for at 825 feet below sea level, Jericho and the other settlements near the Dead Sea are the lowest cities on earth.

It is important to notice that the person has not yet arrived in Jericho when the robbers attack. The person is on the steep way down to Jericho, but he or she has not yet reached the bottom. The road may thus represent the path of this worldly life. Latter-day Saints might not see Jericho as representing this world, but rather as pointing toward the telestial or lowest degree of glory (or perhaps even outer darkness) in an ultimate sense, looking to some future final judgment or doom from which all mankind can be saved. The attack of the robbers and the intervention of the Samaritan stem that course and take the traveler in a more wholesome direction.

Fell. This may refer either to the fall of Adam or to individual human failings. Ambrose blamed this fall on “straying from the heavenly mandate.” It is easy to see here an allusion to the fallen mortal state, the general circumstances of the human condition, or the natural man, as well as the plight of the individual sinner.

Among thieves. The early Christian writers saw here a reference to “the devil,” “the rulers of darkness,” or “evil spirits or false teachers.” Latter-day Saints may want to add a further dimension to this discussion, for these thieves (or rather bandits or robbers, such as the Gadianton robbers) are not casual operators but organized outlaws. The traveler is assailed not by random spirits, but by a band of highwaymen, a pernicious, scheming, organized society that acts with deliberate and concerted intent.

Which stripped him of his raiment, and wounded him, and departed, leaving him half dead.

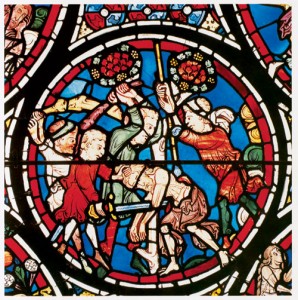

This scene from the Bourges window shows the traveler falling among robbers and appears in the context of scenes depicting the creation and fall of Adam.

Stripped of his raiment. The early Christians sensed that Jesus spoke of something important here. Origen and Augustine saw the loss of this garment as a symbol of mankind’s loss of immortality and incorruptibility. Chrysostom spoke of the physical loss of “his robe of immortality” and the moral loss of the “robe of obedience.” Ambrose spoke of the traveler being “stripped of the covering of spiritual grace which we received [from God].”

The attackers apparently want the person’s clothing. They undress (“strip”) the victim. Oddly, no mention is made of the traveler’s wealth or any commodities he or she might be carrying. Nothing in the story indicates that the person is carrying anything at all (although one may assume that the person has sufficient for the needs of the journey). And yet for some undisclosed reason, the attackers seem to be particularly interested in the traveler’s garment. At least the stripping receives special mention. Perhaps they want this clothing not only for its inherent use as fabric (just as the soldiers divided the garments of Jesus at Golgotha, Matt. 27:35), but also to claim its social status or privileges or powers; or maybe they want to deny the person the privilege of wearing something distinctive or sacred, somewhat reminiscent of the story of Joseph’s coat taken by his brothers. In any case, according to Origen the robes are not only taken off, but also “taken away.”

Wounded. The early Christian writers consistently mentioned here references to the pains of life, the travails of the soul, the afflictions due to diverse sins and vices. Latter-day Saints would agree: sin and the enemies of the soul do indeed wound the spirit.

Half dead. The robbers depart, leaving the person exactly “half dead.” We may see in this detail a reference to the first and second deaths. The person had fallen, had become subject to sin, and thus had suffered the first death, becoming subject to mortality. But the trav-eler is only half dead; the second death (permanent separation from God) can still be averted. Some early Christians understood this element in the story this way, but then the notion drops out of later commentaries.

And by chance there came down a certain priest that way: and when he saw him, he passed by on the other side. And likewise a Levite, when he was at the place, came and looked on him, and passed by on the other side.

By chance. In other words, the arrival of the Jewish priest is not the result of a conscious search on his part. This priest is not out looking for people who are in need of his help. He is simply there “by chance.”

A certain priest. The early Christian commentators saw this as a reference to the law of Moses or to the priesthood of the Old Testament, which did not have the power to lead to salvation. In New Testament times, the priests in Jerusalem were aristocratic clergy who administered the affairs of the temple. Many of the ruling priests were Sadducees, who were largely sympathetic with Hellenism and the Roman authorities. Thus, this figure may point to any religious leader who might rely on the doctrines of men that do not have the power to bring people into eternal life.

A Levite. The priest and the Levite were seen by early commentators as representing the law and the prophets of the Old Testament, which Jesus came to fulfill (Matt. 5:17). The Levites were a lower class of priest, relegated to menial chores and duties within the temple. If they were lucky, they served as singers and musicians; otherwise they swept the porches and open parts of the temple area. At least this lower Levitical priest comes close to helping the fallen victim. The Levite “came” and saw. Perhaps he wants to help, but views himself as too lowly to help; even more than the priest, he also lacks the power or authority to spiritually save the dying person. In the end, he also looks away and passes by on the other side.

But a certain Samaritan, as he journeyed, came where he was: and when he saw him, he had compassion on him, and went to him, and bound up his wounds, pouring in oil and wine.

Samaritan. The early Christians clearly saw the good Samaritan as Christ himself, “the keeper of our souls” (Chrysostom), “the guardian”(Origen), “the good shepherd “(Augustine), “the Lord and Savior” (Eligius). Chrysostom suggested that a Samaritan is a particularly apt representative of Christ because “as a Samaritan is not from Judea, so Christ is not of this world.” Modern readers, for the most part, have lost this plain point of view.

Jesus’ audience in Jerusalem, however, may well have recognized in Jesus’ Samaritan a reference by the Savior to himself. In the Gospel of John, some Jews in Jerusalem rejected Jesus with the insult, “Say we not well that thou art a Samaritan, and hast a devil?” (John 8:48). Perhaps because Nazareth is right across the valley to the north of Samaria, the two locations could easily be lumped geographically together. And just as the Samaritans were viewed as the least of all humanity, so it was prophesied that the Servant Messiah would be “despised and rejected of men” and “esteemed . . . not” (Isa. 53:3).

The priest and the Levite pass by the wounded man in this scene from the Chartes window. In the Bourges and Sens windows, this scene is surrounded by image of Moses, showing that the priest and Levite represent the law and the prophets of the Old Testament.

As he journeyed. The text may imply that the Samaritan (representing Christ) is purposely looking for people in need of help. Origen, especially, took note that “he went down [intending] to rescue and care for the dying man.” The New Testament text makes it clear that the others come “by chance,” but the text does not give the impression that the Samaritan’s arrival is by happenstance.

Had compassion. This is one of the most important words in the story. It speaks of the pure love of Christ. The Greek term used here literally means that the Samaritan’s bowels are moved with deep, inner sympathy. This Greek word is used elsewhere in the New Testament only in sentences that describe God’s or Christ’s emotions of mercy and in the original parables of Jesus. In addition to its use in the good Samaritan story, this verb appears prominently in two other New Testament parables: in the parable of the unmerciful servant, when the lord, representing God, “was moved with compassion” (Matt. 18:27); and in the parable of the prodigal son, when the father, again representing God, sees his son returning, he “had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him” (Luke 15:20). Likewise, the Samaritan represents the divine compassion of God.8

Went to him. The injured traveler cannot move, but the Samaritan comes to succor him in his hour of greatest need. Similarly, Christ runs to the side of those who suffer and comes to their aid. Without this help, the victim has no hope for recovery or progress.

Bound up his wounds. For Clement the wounds are dressed with love, faith, and hope, “the ligatures . . . of salvation which cannot be undone.” For Chrysostom “the bandages are the teachings of Christ” which bind us to righteousness. Latter-day Saints will understand that the repentant person is bound to the Lord through covenants. Inasmuch as the robbers have carried off the garment of the traveler and have left him stripped, the Samaritan begins the process of replacing the lost garment or rebuilding the victim’s spiritual protection by binding the wounds—”to bind up the brokenhearted” (D&C 138:42)—with these bandages.

Oil. A lotion of olive oil would have been very soothing. While most early Christian writers saw here only a symbol of Christ’s words of consolation, Chrysostom saw the oil as a “holy anointing.” This may refer to many ordinances or priesthood blessings: the initial ordinance of anointing (Ps. 2:2; 18:50; 20:6), the use of consecrated oil to heal the sick (James 5:14), the gift of the Holy Ghost (often symbolized by the anointing with olive oil), or the final anointing of a person to be or become a king or a queen. The names Christ and Messiah literally mean “the anointed one,” and accordingly, with this oil the Christ figure gives his very essence to the needy soul.

Wine. The Samaritan pours his wine into the open wounds to cleanse them. Later Christian writers saw this wine as the word of God, something that stings. But the earliest Christian interpretation associates the wine with the blood of Christ. The redeeming blood of Christ, symbolized in the administration of the sacrament, purifies the body and soul. A good Samaritan brings not only physical help but also the saving ordinances of the gospel. This atoning wine may sting at first, but it soon brings healing and purity.

And set him on his own beast, and brought him to an inn, and took care of him.

Set him on his own beast. Christ, fulfilling prophecy, bears “our sicknesses” (Matt. 8:17 quoting Isa. 53:4). Augustine said that to be placed on the beast is “to believe in Christ’s incarnation,” for in the flesh Jesus bore our sins and suffered for us.

Although the text does not specify what kind of beast is involved, it may well be an ass, prefiguring a sharing of the Lord’s beast of triumphal entry, with Christ allowing each person whom he rescues to ride as the king himself.

Inn. For the early Christians this element readily symbolized God’s church. An inn was a public house open to all. A wayside inn, a public shelter, or a hospital, all of which are implicit here, offer meaningful symbols for the Church of Christ. An inn is not the heavenly destination, but a necessary aid in helping travelers reach their eternal home.

Took care of him. The Samaritan stays with the injured person and takes care of him personally the entire first night. He does not turn the injured person over too quickly to the innkeeper; he stays with him through the darkest hours. As Origen commented, Jesus cares for the wounded “not only during the day, but also at night. He devotes all his attention and activity to him.”

And on the morrow when he departed, he took out two pence, and gave them to the host, and said unto him, Take care of him; and whatsoever thou spendest more, when I come again, I will repay thee.

On the morrow. The early commentators saw here the prophecy that Jesus would be resurrected, that he would come again after his resurrection. In other words, Christ ministered in person to his disciples for a short time, for one day and through that night; but “on the morrow” when he departed (that is, after his death, resurrection, and ascension), he left the traveler in the care and keeping of the Church. For Latter-day Saints, however, the dawning of the new day in the life of the rescued victim naturally relates to the beginning of the convert’s new life, enlightened by the true light of a new dawn.

Two pence. Early on, the elders saw these coins (which would have borne the images of Caesar) as symbolizing the Father and the Son, the one being the identical image of the other (Heb. 1:1–3). Others thought these coins represented the Old and New Testaments; Augustine identified them with “the two instructions on charity” in Luke 10:27. One might suggest that they could also represent in modern times the two priesthoods, or any two witnesses to the truth.

Because the two pence (denarii) would represent two days’ wages, these coins could well represent making adequate provision for the needs of the person. If Jesus is saying, “I will pay you for two days’ work,” then he may also be implying that he will return on the third day.

In addition, the amount of the temple tax owed by each Jewish male in Jesus’ day was half a shekel, or two denarii. Thus, in another interpretation, the Samaritan can be seen as leaving enough money to cover the person’s annual temple tax, or in other words, leaving him in good standing within the house of the Lord.

Innkeeper. The early commentators saw the innkeeper as the apostle Paul or the other apostles and their successors. If the inn refers to the Church in general, however, the host could be any Church leader who takes responsibility for the nurturing and retaining of any rescued and redeemed soul.

When I come again. The Samaritan openly promises to come again, a ready allusion to the Second Coming of Christ. The Greek word translated here as “to come again” appears only one other time in the New Testament, in Luke 19:15, referring to the time when God would return to judge the people for their use of the talents or pounds they have been given.

Repay or reward. The innkeeper is promised that the Samaritan will cover all the costs, “whatever you expend.” The Greek word implies that the innkeeper should spend freely, even to the point of wearing out or exhaustion. The Lord will make the worker whole in the day of judgment.

Beyond that, the text implies more than simply that the Samaritan will reimburse the innkeeper upon his return. He will “reward” the worker generously and appropriately. The Greek word used here is used also in Matthew 6:4, 6:18, 16:27 and Luke 19:8, where the topic is also God’s great, eternal rewards to the righteous.

Perhaps more than any other element in the story, this promise of the Samaritan to pay the innkeeper whatever it costs—in effect giving him a blank check—has troubled commentators who try to visualize this story as a real-life event. Who in his right mind in the first century would give such a commitment to an unknown innkeeper? But when the story is understood allegorically, it becomes clear that when the Samaritan (Christ) makes this promise and gives the innkeeper his charge, they already know and trust each other quite thoroughly.

SEEING WITH ETERNAL PERSPECTIVE

The allegorical interpretation remained the dominant understanding of this New Testament passage well into the Middle Ages. Even Martin Luther retained the basic elements of the traditional allegorical interpretation in his sermon on Aug. 22, 1529.

The rise of humanism, scholasticism, individualism, science, and secularism during the Enlightenment, coupled with Calvin’s strong antiallegorical stance9 and capped off with the dominantly historical approach to scripture favored in the 19th and 20th centuries, eventually led scholars to see little more in this text than a moral injunction to be kind to all people10 and a criticism of organized religion as not having the power to benefit mankind.11 In the 18th and 19th centuries, “the Christological interpretation almost completely disappeared.”12

Historical analysis has, of course, increased our knowledge about the real-life backgrounds to the story of the good Samaritan, such as informing us about the animosity between the Jews and the Samaritans at the time of Jesus; or about the rabbinic debates over the Jewish law on loving one’s neighbor; or about concerns over ritual purity that might have inhibited a Jewish priest or the Levite from helping the injured traveler. But these points have limited usefulness. For example, while it may have been hard for a Jew to admit that a Samaritan had been a neighbor to the injured man, we know nothing about the ethnicity of the beaten man himself. He may have been another Samaritan, a Gentile, or a Jew. Without knowing the victim’s identity, we know little about the social nature of the Samaritan’s compassion. Hence, historical information about hostility between Jews and Samaritans, while interesting in gauging the Pharisee’s reaction, is largely irrelevant or superfluous to one’s becoming or being like the Savior. If Jesus’ purpose was to instruct people to be kind to those outside one’s normal circle of friends, he should have clearly identified the victim as, for instance, a Jew or a Roman. Jewish debates may have prompted the lawyer’s questions, but they did not dictate Jesus’ answer.

Indeed, several parts of the story should tip us off that the parable is more allegorical than historical. For example, rarely in the ancient world did people travel alone. That was too dangerous. Yet in this story we have a string of solo travelers: the man who went down, the priest, the Levite, and the Samaritan are alone. Moreover, other necessary elements in the story, such as the innkeeper’s willingness to incur large personal expenses on the unsecured promise of repayment from a Samaritan, of all people, should signal to the reader that a deeper level of meaning stands behind this parable, as was the case with all of Jesus’ parables (see Matt. 13:10–11).

Understanding this parable allegorically adds an eternal perspective to its moral message and spiritual guidance. This reading positions deeds of neighborly kindness within an expansive awareness of where we have come from, how we have fallen into our present plight, and how the binding ordinances and healing love of the promised Redeemer and the nurture of his Church can rescue us, provided we live worthy of the reward.

In the light of the plan of salvation, the parable gains a compelling eternal mandate. Reading this parable through a Christ-centered approach, one sees Jesus’ story more clearly as encouraging people to “accept the Savior’s atoning payment” by showing mercy and love to their fellow beings.13 Jesus told this story not so much to answer the question, “Who is my neighbor?” but ultimately to respond to the query, “What shall I do to inherit eternal life?” If the lawyer was eventually able to understand enough to go and do like the Samaritan, then he would have been set on the path to realizing his own divine potential to ultimately become like the Savior himself.

Reading the good Samaritan in this way invites readers to identify with virtually all of the characters in the story. On one level, Christ surely intended all people to see themselves as the good Samaritan in a physical sense and also as saviors on Mount Zion in a spiritual sense, aiding in the cause of rescuing lost souls. He told the Pharisee, “Go, and do thou likewise” (Luke 10:37). By doing this, we join Christ in bringing to pass the salvation and eternal life of mankind.

Disciples, however, may also want to think of themselves as the innkeeper, and go and be like that man who tends to the long-term recovery needs of the injured traveler. Eventually it is the innkeeper who receives the Samaritan’s promise of reward.

Or again, the reader may identify with the traveler himself. There is power and virtue in reaffirming, in the end, the urgent need we all have to be saved.

As shown in the Chartres window, early commentators believed the Samaritan stayed with the traveler through the night in the inn (note the burning lamp behind the Samaritan). That the Samaritan represented Jesus to early Christians is evident in the Bourges and Sens windows, which associate the rescue by the Samaritan with scenes from the suffering and resurrection of the Savior.

In addition, we may need to see ourselves as the priest or Levite, lacking the power to fix certain problems, as much as we might want to. Or we might even, on occasion, play the role of the robbers, for after all, we too sometimes harm or injure our fellowman. In other words, we may at one time or another identify with every character in this masterful story.

Seeing the parable of the good Samaritan as a capsule of the plan of salvation offers a strong, respectable reading of this text. The strength of seeing this text as an allegory is derived largely from the fact that all the elements in the story fit naturally and easily into place in the overall layout, especially in light of the restored knowledge of the plan of salvation. The pieces all interlock and fit together, as they should if they were designed to be understood that way. A Latter-day Saint construction of the allegory makes even stronger sense of each of its elements, showing again how the scriptures “truly testify of Christ” (Jacob 7:11). This teaching of Jesus truly answers the most pressing question of all existence: how can one obtain eternal life?

John W. Welch is the editor in chief of BYU Studies and the Robert K. Thomas Professor of Law at BYU‘s J. Reuben Clark Law School.

Notes

1. Joseph Smith Jr., History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2d ed., rev. 7 vols. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1971), vol. 5, p. 261.

2. Malcolm Miller, Chartres Cathedral (Andover, Eng.: Pitkin Pictorials, 1985), p. 68.

3. For a full discussion with footnotes, see John W. Welch, “The Good Samaritan: A Type and Shadow of the Plan of Salvation,” BYU Studies, vol. 38, no. 2 (1999), pp. 51–115. Other Latter-day Saints, including Hugh Nibley, Brent Farley, Stephen Robinson, Lisle Brown, and Jill Major, have independently understood this parable in a similar manner.

4. For documentation on quotes attributed to these patristic sources, see the footnotes in Welch, “The Good Samaritan,” pp. 105–15.

5. Jean Daniélou, “Le Bon Samaritain,” in Mélanges bibliques: Rédigés en l’honneur de André Robert (Paris: Bloud and Gay, 1956), pp. 457–65.

6. Leonard J. Coppes, “‘¯ad¯am,” in Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament, ed. R. Laird Harris, Gleason L. Archer Jr., and Bruce K. Waltke, 2 vols. (Chicago: Moody, 1980), vol. 1, p. 10; Fritz Maas, “‘¯ad¯am,” in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, ed. G. Johannes Botterweck and Helmer Ringgren (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmans, 1974), vol. 1, pp. 75–87.

7. See Barry J. Beitzel, “Travel and Communication,” in Anchor Bible Dictionary, ed. David Noel Freedman, 6 vols. (New York: Doubleday, 1992), vol. 6, pp. 644–46.

8. John Durham Peters, “The Bowels of Mercy,” BYU Studies, vol. 38, no. 4 (1999), pp. 27–41.

9. Hans Gunther Klemm, Das Gleichnis vom barmherzigen Samariter: Grundzüge der Auslegung im 16./17. Jahrhundert (Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 1973), pp. 129–41.

10. James C. Gordon, “The Parable of the Good Samaritan (St. Luke 10:25–37): A Suggested Re-orientation,” Expository Times, vol. 56 (1944–45), pp. 302–304.

11. Hermann Binder, “Das Gleichnis vom barmherzigen Samariter,” Theologische Zeitschrift, vol. 15 (1959), pp. 176–94.

12. Werner Monselewski, Der barmherzige Samariter: Eine auslegungsgeschichtliche Untersuchung zu Lukas 10, 25–37 (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr, 1967), p. 159.

13. S. Brent Farley, “The Parables: A Reflection of the Mission of Christ,” in A Symposium on the New Testament (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1980), p. 78.