By Jeff Call, ’94

I had heard the stories about Mitt Romney, ’71. Had a bulging file full of them. Too good to be true. Over the years those were the words many reporters and pundits had used to describe Romney, the chief executive officer of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC) and the man behind the 2002 Winter Olympic Games.

There was the time a coworker’s teenage daughter was missing and Romney, then a millionaire venture capitalist, shut down his company’s operations and took to the streets of New York City, searching for her door-to-door. She was found, in New Jersey, after articles about the search hit the newspapers.

People had described him as telegenic, charismatic, and savvy. In 1994 he challenged Sen. Edward Kennedy, a Massachusetts icon, for his seat. Romney lost the campaign, but gave Kennedy a major scare. Had Romney been able to win, it would have been one of the greatest upsets in American election history. He garnered 41 percent of the vote—not bad, considering only 13 percent of registered voters in the state are Republicans. “It was like being in a ski race with Jean-Claude Killy,” Romney later joked.

There are the amazing tales of his business acumen.

After graduating in English with highest honors from BYU, Romney received an MBA from Harvard Business School and his juris doctor, cum laude, from Harvard Law School. He cofounded a Boston-based venture capital firm in 1984. Under his guidance businesses like Staples and Domino’s Pizza turned staggering profits.

Then there’s his unusual name. Actually, his first name is Willard, in honor of hotel chain magnate J. Willard Marriott Sr., a friend of the Romney family. His middle name, Mitt, came from an uncle who was a Chicago Bears quarterback in the 1920s.

Friends and colleagues had mentioned his sense of humor, self-effacing manner, and down-to-earth persona. Last summer SLOC released a top-10 list, David Letterman style, of Romney’s most memorable bloopers. One of those mistakes mentioned was a fund-raiser featuring bricks on which the names of donors were to be carved, except those bricks dissolved in cold weather.

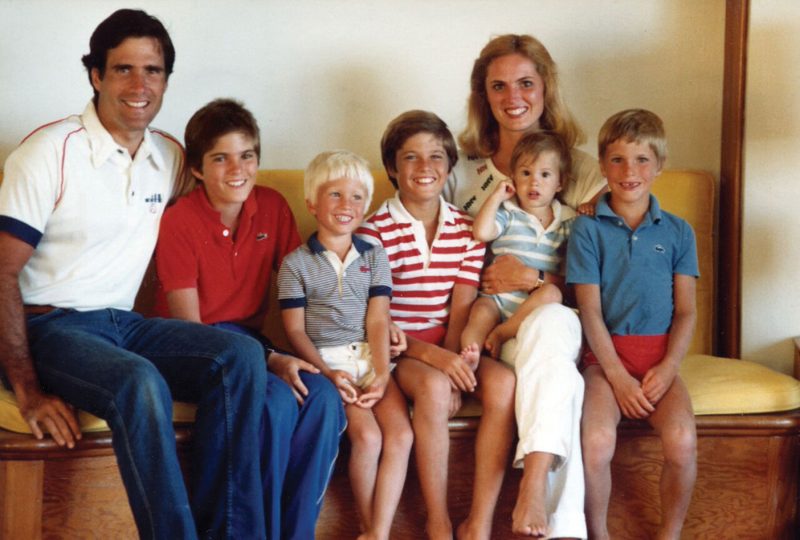

People had also said he is the ideal family man and devoutly religious. He and his wife of 31 years, Ann, have raised five sons, all of whom have either attended or graduated from BYU. People had brought up his membership and service in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as well as his involvement in philanthropic enterprises and charities such as the Points of Light Foundation and the Boy Scouts of America. “Are they out of a time warp or something?” the Boston Herald once asked about the Romneys.

The day of my interview with Romney, I arrived late for the appointment at SLOC headquarters in downtown Salt Lake City. While riding the elevator to the 13th floor, I thought I had squandered my chance to talk to arguably the busiest man in Utah. An SLOC aide found Romney and explained the situation. Seconds later, Romney’s 6-foot-2 frame emerged. He appeared fit and trim with dark hair and Hollywood good looks, just as he had been described. He smiled warmly, ushered out another appointment, shook my hand vigorously, called me by name, and invited me to take a seat opposite him in his modest office. Romney sat in front of a window with a majestic view of the Wasatch Mountains over his shoulder.

Certainly Romney had plenty on his mind. From Feb. 8 to 24, Utah will host the world and stage the largest Olympic Winter Games in history. The budget is $1.32 billion for the Winter Olympic Games and the Paralympic Winter Games, which follow in March. He oversees more than 700 employees and 26,000 volunteers. The Games are made up of 78 events and 165 sport sessions. A total of 234 medals will be awarded. The extravaganza will be watched by billions of viewers worldwide, and Romney will be in the global spotlight.

During the interview, he seemed calm. He was gracious, patient, and witty. He looked me straight in the eyes. Never mind that he had answered many of the same questions countless times from the largest media outlets on the planet. He responded thoughtfully to each query. It became obvious that he loves his job.

“It has been very enjoyable to work in the Olympic movement and to meet the athletes who have long been heroes,” Romney told me. “I’ve found people like Kristi Yamaguchi and Dan Jansen and Picabo Street and other famous Olympians and future Olympians to be inspiring. Working for causes that are more than just putting bread on my table is a pretty compelling endeavor.”

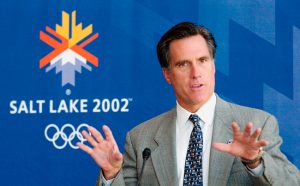

It was the winter of 1999, and a dark cloud hung over the state of Utah. An Olympic bid scandal had broken open, and SLOC was stuck holding the pieces. Both the Olympic and the state images were tarnished by allegations of bribery. Sponsors were jumping ship, the U.S. Justice Department was conducting an investigation, and the U.S. Senate was about to hold hearings. Around the nation and the world, fair or not, Utah had suddenly become synonymous with the word scandal.

The 2002 Winter Games were on the brink of becoming one of the most conspicuous failures in the history of sport. The reeling SLOC desperately needed a new leader, someone who was squeaky clean, someone who had integrity, someone who could restore the world’s faith in the Olympic movement. But did such a person exist? A search was launched. “The candidate I’m looking for,” SLOCchairman Bob Garff said at the time, “is the white knight who is universally loved.”

SLOC found its white knight in Romney. And on the morning of Feb. 11, 1999, Romney took on the responsibility of rescuing the Olympics. People didn’t know whether to congratulate or console him.

At the press conference Romney immediately began to win over even the most jaded skeptics. He apologized for SLOC’s mistakes. He promised that the Games would be run with impeccable ethical standards and that they would break even financially. And, finally, he said he aimed “to put on the best Winter Olympics in history.”

Romney may have sounded crazy, but he proved it wasn’t empty rhetoric as he turned down the $285,000 annual salary that accompanied the job and contributed a reported $1 million of his own money to the Olympic effort.

“We began in a pretty deep hole following the bid scandal,” Romney recalled that day in his office. “The community was disheartened. Our financial crisis, which was less visible, was just as severe. We were $379 million out of balance between our revenues and our costs.”

Nearly three years later and with the 2002 Games just around the corner, Romney has achieved what can only be called a miraculous turnaround. Not only has he managed to shear millions of dollars from the deficit, he has helped to pull in more than $180 million in new sponsor revenue. He instituted numerous cost-cutting measures, including the elimination of lavish, expensive perks. “Financially, we’re back on solid foundation,” he said. What’s more, he has helped the public almost forget about the scandal altogether. Time, with a big boost from Romney and his staff, have healed many of the wounds inflicted by the bid controversy. No wonder Romney has been referred to as the man who may have saved the 2002 Games.

“Fortunately, the community has rallied to the Olympics and recognized that this is about sport, about young athletes, and about showcasing great qualities of the human spirit,” Romney said, a smile spreading across his face. “They don’t care so much about the old managers like me; they care a lot more about the young athletes and the spirit and values which they show the world. And so the community has rallied around the Games.”

Those who know Romney well are not surprised by SLOC’s changes in fortune. After all, he has a reputation for making the most of the bleakest of circumstances. Though taking the reins of the 2002 Winter Games may have been his biggest challenge, it was far from his first.

Romney has never let a little adversity stand in his way. In fact, he seems to relish against-all-odds situations. As the youngest son of late Michigan governor George Romney, Mitt watched his father help save a floundering American Motors Corp.

Mitt attended prep school and ran cross country in Bloomfield Hills, an upscale suburb in the Detroit area. During a particular race, Romney fell woefully behind. His legs trembled and his stomach ached. Knowing he had no shot at winning the race, he nevertheless pressed on and tripped headlong onto the ground. Romney stood up and stumbled toward the finish line, where he collapsed. He was hauled away on a stretcher. In a way that story serves as a metaphor for what he has done numerous times. “The Romneys aren’t known for having athletic talent,” he has said, “but we are known for giving our all.”

Mitt soon left Michigan to enroll at Stanford. Following that first year he departed for a Church mission to France, which, he admits, was a humbling experience. While Mitt served his mission, his father contended for the 1968 Republican presidential nomination, but lost.

When he returned from France, Mitt followed his high school girlfriend, Ann, to BYU, where they continued their courtship. They married and moved to Boston so he could attend Harvard’s business and law schools. With no income they sold Mitt’s stock in American Motors to survive.

After graduating Romney joined the Boston-based Bain & Co. Six years later he cofounded and was named CEO of Bain Capital, now worth a reported $5 billion. By the early 1990s he had decided to pursue political ambitions. He couldn’t have selected a more formidable confrontation. A huge underdog as a conservative Republican, Romney surprisingly gave Sen. Kennedy the closest political race he had ever had.

The unflappable Romney returned to his business and continued to prosper.

Ann played a large role in the Romneys’ moving back to Utah in 1999. The state was mired in its Olympic bribery scandal and local businessman Kem Gardner, who knew the Romneys from his service as a Church mission president in Boston, called Ann, explaining that Mitt would be a perfect fit for the SLOC. When Ann broached the subject with her husband, his first reaction was, “What do I know about the Olympics?” But he soon warmed to the idea, partly because of his strong Utah roots. Also, he was attracted to the position because, of course, he specializes in lost causes. Ann was eager for the task, too. She joked that, compared to raising five sons, the Olympics would be a piece of cake.

And although at times Romney may have made the job look easy, the trials have continued.

On Sept. 11, 2001, when terrorists brutally attacked the United States, questions abounded about the safety of the 2002 Winter Games. Many wondered aloud if the Olympics should be held at all. Romney responded respectfully and intrepidly. “Tears and prayers flood our hearts. But not fear. As a testament to the courage of the human spirit, and as a world symbol of peace, the Olympic Games are needed even more today than the day before,” he said in a prepared statement two days after the attacks.

“The Olympics are about courage,” he stated. “The Games represent the greatest qualities of the human spirit, including world peace. The message of the Olympics is even more important today than before.”

Since that time Romney has devoted much attention to public safety at the Games. He is confident that the Olympics will be safe and enjoyable for observers as well as participants.

That day in his office, I asked Romney to fast-forward to March. What does he hope the Olympics will have accomplished once they are over? “I would like the people of the world who watched the Games on TV or were here to say, ‘Well, Salt Lake got off on a rocky footing, but they did a great job, fulfilled their commitment to the world, and hosted a great Games,'” Romney said. “We have a motto for the Games, which is Light the Fire Within, and I believe that by coming to Salt Lake City, if we do our job well, people will go away feeling like they have had a fire lit within them or they’ve been inspired by the athletes and by the people they’ve met here and by their fellow citizens from around the world.”

As for post-Olympic plans, Romney’s name has surfaced as a candidate for governor of Massachusetts in 2002. But he told me he does not know what his future plans entail, though he does know he won’t return to the business world.

“I want to remain involved in public service of one kind or another,” he said. “I had a run at political office, and I will consider that again if the opportunity arises. But I’ll also look at other charitable endeavors I’ve been involved with. It’s perhaps not a surprise that having tasted the Olympic experience, I have grown accustomed to the flavor and want to continue to serve. If the opportunity is available after the Games, I hope to be able to continue in that vein.”

By the time the interview was over, Romney was already late for his next appointment. Yet he escorted me out of his office, through the lobby, and to the elevator. He shook my hand again.

“It was nice to meet you,” he said. “Thanks for coming.”

Now I had my own Mitt story to add to the collection.

OLYMPIC DREAMS AT 80 MPH

By Todd R. Condie, ’03

From the first time she stepped on a soccer field at BYU until her last game in 1998, Shauna L. Rohbock, ’99, dominated. Leading the team in scoring all four years she played, Rohbock earned three All-America citations during her career. Adding two other All-America awards she earned in the heptathlon makes Shauna Rohbock one of the most highly decorated female athletes in the university’s history. But she isn’t finished yet. If Rohbock has her way, she will become only the second BYU alum to medal in the Winter Olympic games.

Shortly before the end of her senior year, Rohbock and several other heptathletes from BYU were recruited by Bonny Warner, a member of the U.S. national bobsleigh team. Despite having only practiced pushing a sled for a few days, Rohbock made the team as a brakeman. In only her first year competing, Rohbock and her driver, Jill Bakken, placed second in the world.

Now Rohbock is entering her third year of international competition and has her sights set on competing for the gold medal in Salt Lake City, the first time women’s bobsleigh will be a medal event. As a brakeman, she helps her driver at the beginning of the run to propel the sled, which can weigh up to 700 pounds. As they descend, Rohbock counts turns so that she can brake when the run is over. During a typical 60-second run, her sled reaches speeds of nearly 80 mph.

Of her new sport, Rohbock says, “When I first saw it, I thought it would be easy. The brakeman runs 30 or 40 meters and gets in. I thought, I ran for 90 minutes in soccer and did seven events in the heptathlon. This is going to be cake. But it’s actually very physically and mentally challenging. But the feeling of it is amazing.”

Only two of the national team’s three sleds will compete in Salt Lake City, but Rohbock is confident of her chances.

Even if successful, Rohbock won’t be the first Winter Olympian to have emerged from BYU’s ranks. Barbara D. Lockhart, ’71, now a BYU professor of physical education, competed in speed skating in both 1960 and 1964. Jean M. Saubert, ’76, also competed in 1964, earning a silver medal in the giant slalom and a bronze in the slalom.

UPDATE: As this magazine was going to press in mid-December, Shauna Rohbock’s plans suddenly changed. Driver Jill Bakken selected a new brakeman a week before the Olympic trials, sending Rohbock home earlier than she had hoped.

HOSTING THE WORLD

A common saying in Utah recently has been that the Olympics are bringing the world to our doorstep. BYU can say the same. Many Olympic visitors will come to Provo to see everything from hockey and skating events to cultural performances. But even those who don’t visit campus may get a taste of BYU.

GO FORTH TO SERVE

Of the more than 26,000 volunteers that are expected to help stage the Olympic Games, almost 4,000 are current BYU students. And as of October—with hiring just beginning—nearly 600 more students were scheduled to be either full- or part-time employees of the Salt Lake Organizing Committee (SLOC) during the Games. BYU students will serve as events staff, interpreters, and family hosts as well as weather aides and medics. In addition to students, thousands of BYU alumni are volunteering for or are employed with the Games.

Jennifer R. Kusch, ’02, BYUSA vice president of campus activities and a student volunteer, says, “As soon as I found out that they were recruiting volunteers, I wanted to do it. I feel like it is going to be an amazing experience to meet people, to serve people, and to learn about new cultures. There’s a huge level of excitement among the volunteers just because it’s so close to home.”

BLUE AND WHITE AMBASSADORS

Mitt Romney is one of many BYU alums behind the scenes of the 2002 Winter Olympics. Fraser Bullock, ’78, SLOC’s chief operating officer and chief financial officer, engineered the Salt Lake Games’ financial turnaround (see marriottschool.byu. edu/marriottmag). In addition, former Cougar quarterback Steve Young, ’84, is the titular head of the thousands of Olympic volunteers and will emcee the presentation of gold, silver, and bronze medals each night.

A CELEBRATION OF CULTURE

The music and dance of BYU will be seen from the opening ceremonies to the closing ceremonies and just about everywhere in between as more than a dozen BYU groups participate in Olympic entertainment.

Many BYU ensembles will be showcased in The Light of the World, a stage extravaganza in the Conference Center of the Church of Jesus Christ. Randall W. Boothe, ’79, a BYU associate professor of music and codirector of the production, says, “I have received nothing but the most enthusiastic and willing responses from our performing groups, even while rehearsing in a parking lot under a hot sun. These students have toured the world and have a real appreciation for the people who have welcomed them so warmly. This is their chance to pay back that hospitality.”

BYU groups will also perform at the Assembly Hall on Temple Square, the Olympic Village, various competition venues, and downtown Provo.

GUIDING THE FLAME

You can discover where Leonard R. Moon is today by finding out where the Olympic torch is. A former BYU ROTC commander and current admissions office employee, Moon is the troubleshooter for the Olympic flame’s course to Utah through the United States. Also assisting with the torch run are BYU student Steven E. Mott and graduate Alicia A. Keller, ’00.

Moon left from Atlanta just after Thanksgiving and will arrive in Utah Feb. 8. By then he will have logged some 13,500 miles and worked with thousands of runners. When he gets to Utah, he and his wife will get to run with the torch themselves. Barbara D. Lockhart, ’71, a former Winter Olympian and a BYU physical education professor, will also run with the torch in Utah.